Removing the Institutional Debt Hurdle

Findings from an Evaluation of the Ohio College Comeback Compact

Executive Summary

This report provides findings from the evaluation of the pilot year of the Ohio College Comeback Compact, an institutional debt cancellation program being implemented at eight public institutions in northeast Ohio. The Compact provides up to $5,000 in debt cancellation for stopped-out students meeting certain requirements. Key findings and recommendations from the evaluation include:

- During the pilot year, 156 students re-enrolled at one of the eight participating institutions. On average, these students owed about $1,500 in institutional debt, had been stopped out for four years, and were 33 years old. Students of color are disproportionately likely to owe an institutional debt as well as participate in the Compact.

- Ninety-three percent of participating students either received debt cancellation or made progress towards their debt cancelation. The success of students who re-enroll in the program underscores the substantial barrier that institutional debt and transcript holds create for students. When these barriers are removed, students re-enroll, earn additional postsecondary credits, and complete credentials.

- We do not observe any differences in short-term success rates across racial/ethnic groups. The increased likelihood of students of color to participate and the parity in outcomes suggests debt cancellation programs can help institutions and states achieve their enrollment and attainment equity goals.

- We suggest pairing the Compact, and other debt forgiveness programs, with access to wraparound services. Students returning to school face a broad range of challenges and providing additional wraparound support is likely to maximize the benefits. Previous survey findings also suggest that some college, no degree students with institutional debts are struggling with food and housing insecurity and general financial constraints.[1] As such, we recommend that institutions coordinate offices and services, including non-institutional sources (e.g., SNAP), and direct Compact participants or would-be participants to these coordinators so students can easily access them. Understanding what is available may be an important factor as students consider returning.

Introduction

It is estimated that as of 2020, roughly 6.6 million students owed $15 billion in unpaid balances to their institutions.[2] These students face three problems: many are unable to access their transcripts, they owe money to the college or university they attended, and they are unable to re-enroll in that institution due to administrative holds. As a practical aspect, students may need access to their transcripts in order to transfer institutions or programs, re-enroll in a new institution after a lengthy gap, send transcript copies to scholarship programs, or provide evidence of course taking to employers. Institutional debts cause a host of problems for students by negatively impacting their credit and bringing finance-related stress that can negatively impact mental health. Administrative holds preventing re-enrollment leave students unable to realize the benefits of a postsecondary credential. Fortunately, a number of initiatives and policies, including the Ohio College Comeback Compact, have sought to alleviate this barrier for students.

Several states have imposed full or partial bans on transcript withholding, including California, Washington, and Louisiana, and the federal government recently proposed new rules limiting the practice to only credits earned in the period of the unpaid balance.[3] While these policies are an important step to addressing the problem, most students will still owe an institutional debt and will be unable to re-enroll and complete their credential. Given what we know about the inefficiencies and credit leakage of transfer, banning the practice of transcript withholding does not fully address the dual nature of the problem and does little to alleviate the financial burden and stress associated with debt.[4]

Institution-specific debt forgiveness programs have also developed over the past several years. One of the most well known is the Warrior Wayback Program at Wayne State University, although there are several dozen programs that offer students debt forgiveness and a path back to college. These programs play an important role in helping students with institutional debt and also financially benefit institutions. Previous research suggests that institutions may only collect pennies on the dollar when sending institutional debts to collections.[5] However, by forgiving small debts for students actively seeking to return to school, institutions have unlocked substantial amounts of future tuition revenue that almost always outweighs the debt forgiveness.[6]

The Ohio College Comeback Compact (“Compact” or “Ohio Compact”), launched in August 2022, is a novel approach that seeks to address both aspects of the problem, debt forgiveness and transcript holds, on a regional scale. The Compact consists of eight institutions in northeast Ohio, four community colleges and four public four-year institutions. Students who have a debt under $5,000 with one of these institutions are able to re-enroll in any of the eight institutions and have their debt forgiven (subject to guidelines described below). When a student cross-enrolls at another institution, the newly attended institution subsidizes a portion of the debt forgiveness, at a rate that exceeds what the original institution is likely to collect through a collections process. In this way, the Compact creates a win-win-win scenario where students receive debt forgiveness and the ability to re-enroll or transfer, institutions receive new tuition revenue or a subsidy on their debt forgiveness that is higher than the expected collections rate, and the state of Ohio benefits from additional adult learners with Some College, No Credential (SCNC) returning to school and working towards their credentials.

In order to be eligible for the Compact, individuals:[7]

- must have stopped out of a Compact institution at least one academic year ago, and cannot have stopped out before the year 2000;

- cannot be concurrently enrolled in an associate’s or bachelor’s degree program at another institution;

- must have had a 2.0 or higher cumulative grade point average (GPA) at the time of stopping out;

- must owe a principal balance of $5,000 or less to their former institution, and can only owe a balance to one of the eight institutions; and

- must have had their debt certified to the Ohio Office of the Attorney General (OAG),[8] and the individual cannot be currently involved in bankruptcy proceedings or assigned to special counsel status.[9]

To better understand the effectiveness of this novel approach to addressing institutional debt, we conducted a mixed methods evaluation of the pilot year of the Compact. This included descriptive and multivariate regression analyses of administrative data, student interviews and surveys, and focus groups with campus administrators. We began our evaluation efforts soon after the Compact’s launch in summer 2022 and continued our data collection and analysis until the end of 2023. A primary benefit of and motivation for conducting the evaluation simultaneously with the pilot year was the ability to provide real-time feedback to the implementation team. The group evaluating the program benefited from having strong internal working relationships with the implementation team and a detailed knowledge of the Compact implementation, but operated separately from the implementation team in order to provide an objective evaluation. This quick turnaround of feedback allowed the implementation team to make programmatic tweaks to improve operations and better serve students.

This report focuses on the quantitative analyses conducted during the evaluation. Two separate reports present findings from our qualitative evaluation efforts as well as a survey of students with stranded credits.[10] As part of our evaluation efforts, we accessed student-level administrative data used in the implementation of the Compact which included demographics, previous enrollment and academic information, debt amounts, and re-enrollment status and current academic outcomes. We descriptively analyzed patterns in debt, re-enrollment, and short-term academic outcomes as well as fit multivariate regression models to understand factors associated with participation and success in the Compact. In this analysis we seek to answer three primary research questions:

- Who owes institutional debts at Compact institutions?

- Who participated in the Compact?

- What are the short-term outcomes of Compact participants?

Understanding Who Owes Institutional Debts

To answer our first research question, we examine the 9,109 students who met all the eligibility requirements, described above, during the pilot year. This included 7,857 students who were eligible in Fall 2022 and an additional 1,252 students who became eligible in Spring 2023.[11] Although a wider set of students have institutional debt, we focus our analysis on eligible students because we have the most complete set of data for these students and are able to track their re-enrollment and debt forgiveness. In this section we examine student demographics, institutional debt patterns, and academic backgrounds.

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the 9,109 former students eligible for the Compact in the 2022-2023 school year. Women are more represented than men in the pool of eligible students.[12] Over half of the eligible students are white, 37 percent are Black or African American, five percent are Hispanic and three percent are multiracial. Non-Resident Alien students, American Indian or Alaska Native students, Asian students, and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander students each make up less than one percent each of eligible students. The average age of students is 40 years old, although there is significant variability as indicated by the standard deviation of 13 years. Variables measuring Pell grant receipt and veteran status were heavily affected by missing data, nine percent of eligible students had missing values for the Pell grant variable and 20 percent had missing values for the veteran status variable. Of eligible students with valid information, 62 percent received Pell grants and four percent were military veterans.

Eligible students had an average debt of about $1,000 (median of $726), much lower than the program cutoff of $5,000, demonstrating the heavy skew towards smaller debts. The average student had accumulated 48 credits with a GPA of 2.66 before stopping out. Fifty-nine percent of students have debt held by a two-year institution (Cuyahoga Community College, Lakeland Community College, Lorain County Community College, or Stark State College), and 41 percent have debt held by a four-year institution (Cleveland State University, Kent State University, University of Akron, Youngstown State University). Eligible students had an average time-since-stop-out value of nearly nine years (median of eight years), but the high standard deviation suggests a considerable range in time-since-stop-out that mirrors the variability in age. Compact-eligible students are similar to the national population of Some College, No Credential (SCNC) students in terms of age and community college representation, according to National Student Clearinghouse data from the 2021-22 school year.[13] Women and non-Hispanic white students are more heavily represented in the population of Compact eligible students than in the national SCNC population. Although non-Hispanic students may be overrepresented compared to the national SCND population, they are underrepresented compared to Compact institutional enrollments which reinforces the important racial and ethnic equity implications of addressing this issue.[14]

Table 1a: Characteristics of Compact-eligible students

| Characteristic | Level | Number of Students | Percent of Students |

|---|---|---|---|

| Former Institution | Cuyahoga Community College | 2620 | 28.76% |

| Lakeland Community College | 618 | 6.78% | |

| Lorain County Community College | 1133 | 12.44% | |

| Stark State College | 1026 | 11.26% | |

| Cleveland State University | 655 | 7.19% | |

| Kent State University | 1544 | 16.95% | |

| University of Akron | 951 | 10.44% | |

| Youngstown State University | 562 | 6.17% | |

| Gender | Female | 5545 | 60.88% |

| Male | 3558 | 39.06% | |

| Other | 5 | 0.05% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | Non-Resident Alien | 63 | 0.75% |

| Hispanic | 430 | 5.13% | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 48 | 0.57% | |

| Asian | 64 | 0.76% | |

| Black or African American | 3066 | 36.60% | |

| Native Haiwaiian or Pacific Islander | 7 | 0.08% | |

| White | 4457 | 53.21% | |

| Two or More Races | 241 | 2.88% | |

| Pell Recipient | No Pell | 3191 | 38.34% |

| Pell | 5132 | 61.66% | |

| Veteran | No | 6920 | 95.54% |

| Yes | 323 | 4.46% |

Table 1b: Characteristics of Compact-eligible students

| Characteristic | Average (Mean) | Median | Standard Deviation | Number of students |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unpaid Balance Hold Size | $1084.16 | $726.00 | $1026.94 | 9109 |

| Past Credits Accumulated | 48.13 credits | 37.00 credits | 39.80 credits | 9109 |

| Past Cumulative GPA | 2.66 points | 2.55 points | 0.52 points | 9109 |

| Years Since Stopout | 8.67 years | 8.00 years | 5.43 years | 9109 |

| Age | 40.20 years | 38.00 years | 12.84 years | 9108 |

To understand differences within Compact-eligible students, we used Chi-Square tests and two-sample t tests to compare students from two-year institutions with students from four-year institutions, and students of color with non-Hispanic, white students.[15] Table 2 displays differences across institution types. Two-year institutions have a larger percentage of Black compact-eligible students, while four-year institutions have a large percentage of white students. Compared to students who stopped out of two-year institutions, students from four-year institutions are more likely to have received a Pell grant. Students from four-year institutions have a lower average time-since-stop-out value by one year, and tend to be younger than students from two-year institutions. Finally, students from four-year institutions owe about $1,000 more than students from two-year institutions, and have completed about 20 more credits on average.

Table 2: Differences of characteristics of Compact-eligible students across institution type

| Two Year Institution | Four Year Institution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Percent | Number of students | Percent | Number of students | Difference between groups | Statistical significance (p) |

| Non-Resident Alien, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2% | 119 | 2% | 63 | 0 percentage points | *** |

| Two or More Races | 2% | 119 | 4% | 122 | 2 percentage points | |

| Hispanic | 6% | 293 | 4% | 137 | 2 percentage points | |

| Black or African American | 41% | 2,128 | 30% | 938 | 11 percentage points | |

| White | 49% | 2,556 | 60% | 1,901 | 11 percentage points | |

| Male | 39% | 5397 | 39% | 3711 | 1 percentage point | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 49% | 5215 | 60% | 3161 | 11 percentage points | *** |

| Pell Recipient | 52% | 5397 | 79% | 2926 | 26 percentage points | *** |

| Veteran | 5% | 4265 | 4% | 2978 | 1 percentage point | *** |

| Characteristic | Average Value | Number of students | Average Value | Number of students | Difference between groups | Statistical significance (p) |

| Unpaid Balance Hold Size | $691 | 5397 | $1,656 | 3712 | $965 | *** |

| Past Credits Accumulated | 40 | 5397 | 60 | 3712 | 20 credits | *** |

| Past Cumulative GPA | 2.68 | 5397 | 2.64 | 3712 | 0.04 points | *** |

| Years Stopped Out | 9 | 5397 | 8 | 3712 | 1 year | *** |

| Age | 42 | 5396 | 37 | 3712 | 5 years | *** |

Table 3 shows differences between students of color and students who are non-Hispanic white. Echoing the previous table’s results, a higher percentage of non-Hispanic white students than students of color attend four-year institutions. Non-Hispanic white students are younger by about two years and accumulated more credits before stopping out than students of color, which likely reflects the patterns across two- and four-year institutions. Differences in unpaid balances, GPA, and time-since-stop-out, however, are minor. What does stand out is that 66 percent of students of color received a Pell grant at some point in their previous enrollment, compared to 56 percent of non-Hispanic white students. Coming from a lower-income background and lacking family resources to help with institutional debt likely compounds the hardships for these students. The disproportionate intersection of lower-income background and race/ethnicity underscores the equity issues embedded in the issue of institutional debt.[16] Importantly, the patterns we see across Compact eligible students mirror inequities already present in higher education access and opportunity. Institutional debt is both emblematic of these larger systemic issues and works to reinforcing them for SCND students.

Table 3: Differences of characteristics of Compact-eligible students across race/ethnicity

| People of Color[17] | Non-Hispanic white | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Percent | Number of Students | Percent | Number of Students | Difference between groups | Statistical Significance (p) |

| Male | 39% | 3919 | 38% | 4456 | 2 percentage points | * |

| Four-Year Institution | 32% | 3919 | 43% | 4457 | 11 percentage points | *** |

| Pell Recipient | 66% | 3547 | 56% | 4087 | 10 percentage points | *** |

| Veteran | 6% | 3242 | 4% | 3325 | 2 percentage points | ** |

| Characteristic | Average Value | Number of students | Average Value | Number of students | Difference between groups | Statistical Significance (p) |

| Unpaid Balance Hold Size | $1,049 | 3919 | $1,055 | 4457 | $6.00 | |

| Past Credits Accumulated | 45 | 3919 | 50 | 4457 | 5 credits | *** |

| Past Cumulative GPA | 2.63 | 3919 | 2.7 | 4457 | 0.07 points | *** |

| Years Stopped Out | 9 | 3919 | 8 | 4457 | 1 year | *** |

| Age | 41 | 3918 | 39 | 4457 | 2 years | |

Understanding Who Participated in the Compact

As discussed in the previous section, the issue of institutional debt disproportionately impacts students of color and lower-income students. In many ways, this problem compounds pre-existing inequities that have resulted in these groups being overrepresented among SCND students and facing more significant hurdles repaying educational debts without a valuable postsecondary credential.[18] The Compact serves as an opportunity to reverse these trends and close equity gaps for historically underserved students. In this section we seek to understand who participated in the Compact and how the opportunity of participating related to students’ likelihood of re-enrollment. First, we will share descriptive information about Compact participants. Second, we will examine what individual characteristics were predictive of a student participating. Finally, we will look at re-enrollment rates of eligible and non-eligible students to understand how the offer of debt forgiveness relates to reengagement of stopped out students.

An Overview of Participants

In total, 156 students enrolled in the Compact in the fall 2022 and spring 2023 semesters. Twenty students enrolled in the fall 2022 semester only, and 22 students enrolled in the fall 2022 semester and persisted in the spring 2023 semester. An additional 114 students enrolled in the spring 2023 semester for the first time. Table 4 provides descriptive statistics for the enrolled students. The distribution of students across two-year and four-year institutions is similar for enrolled students as it was for all eligible students. Over half of enrolled students owed a debt to a two-year institution. Women, students of color (specifically Black or African American students), and former Pell recipients are overrepresented in the enrollee population compared to the eligible student population.

Enrolled students had an average unpaid balance of $1,448 (median of $1,120), slightly higher than the average balance of $1,084 for all eligible students. Enrolled students also accumulated more credits while enrolled previously and have been away from school for a shorter period of time than the full population of eligible students.

Thirteen students enrolled in an institution that was different from their debt holding institution. Six students moved between two-year and four-year schools. Two students transferred from a two-year school to a four-year school (Stark State College to University of Akron and Stark State College to Kent State University). Four students transferred from a four-year school to a two-year school (two students moved from Kent State University to Stark State College, one student moved from University of Akron to Stark State College, and one student moved from Kent State University to Cuyahoga Community College). Overall, only 40 percent of SCND students nationwide re-enroll in the same institution from which they stopped out, signifying many of these students were seeking a different postsecondary option or were able to enroll at a different institution more easily due to a registration hold.[19] Among Compact participants, more than 90 percent of students re-enrolled in the same institutions, which suggests their institutional debt and associated registration hold was a major contributing factor to not continuing their studies. By relaxing the registration hold associated with a debt, the Compact has created pathways for SCND students to continue working towards their credential.

Table 4a: Characteristics of enrolled students

| Characteristic | Level | Number of Students | Percent of Students |

|---|---|---|---|

| Former Institution | Cuyahoga Community College | 42 | 27% |

| Lakeland Community College | 9 | 6% | |

| Lorain County Community College | 25 | 16% | |

| Stark State College | 13 | 8% | |

| Cleveland State University | 14 | 9% | |

| Kent State University | 25 | 16% | |

| University of Akron | 22 | 14% | |

| Youngstown State University | 6 | 4% | |

| Gender | Female | 108 | 69% |

| Male | 48 | 31% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | Hispanic | 9 | 6% |

| Black or African American | 73 | 49% | |

| White | 57 | 38% | |

| Two or More Races | 11 | 7% | |

| Pell Recipient | No Pell | 36 | 24% |

| Pell | 114 | 76% | |

| Veteran | No | 116 | 97% |

| Yes | 4 | 3% |

Table 4b: Characteristics of enrolled students

| Characteristic | Average Value | Median | Number of Students | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unpaid Balance Hold Size | $1,447.60 | $1,120.00 | 156 | $1,173.28 |

| Past Credits Accumulated | 57.58 | 52.5 | 156 | 33.89 |

| Past Cumulative GPA | 2.58 | 2.47 | 156 | 0.46 |

| Years Since Stopout | 4.35 | 3 | 156 | 3.79 |

| Age | 32.60 | 31 | 156 | 9.78 |

Predictive Modeling of Enrollment

In addition to descriptively understanding who Compact participants were during the pilot year, we examined the potential for certain student characteristics to be predictive of participation. To do this we used a linear probability model with the outcome variable being a binary indicator that is equal to one if a student enrolled in the Compact during the 2022-23 academic year.[20] This approach enables us to identify individual student characteristics that are related to an increased likelihood of participating in the Compact. Understanding these patterns across different groups of students points to the potential of the Compact and other debt forgiveness programs to advance equity goals and inform outreach and advising strategies to maximize the impact of such programs.

As shown in Table 5, our modeling indicates that participation in the Compact varied across demographic groups. Findings indicate that Black students are roughly 1.5 percentage points more likely to enroll in the Compact than their non-Hispanic white counterparts. There is also some evidence that Hispanic students may be more likely to enroll; however, the finding is inconsistent in size and significance across the models. Students identifying as multi-racial are between two and 2.5 percentage points more likely to re-enroll when the Compact is offered. Given a baseline participation rate of roughly two percent, these effect sizes are both statistically and qualitatively significant. Black students’ likelihood of participating is 76 percent higher and multi-racial students’ likelihood is 106 percent higher than their white counterparts. We do not find evidence that other demographic characteristics are predictive of participation in the Compact including if a student received a Pell grant when last enrolled, if the student is a veteran, the student’s gender, if a student last enrolled in a community college, the student’s GPA, or the number of credits the student previously earned.

We do find a relationship between Compact participation and the length of time a student has been stopped out and the size of the unpaid balance. Extant research suggests that the longer a student is stopped out, the less likely they are to re-enroll.[21] Our model suggests that for every additional year a student is stopped out, their likelihood of re-enrolling decreases by 0.2 percentage points, or 10 percent. We also find that students with larger unpaid balances are more likely to enroll in the Compact. For every $100 of debt a student owes, the likelihood of re-enrollment increases by roughly 0.07 percentage points. That is, a student with $1,500 in debt is approximately one percentage point more likely to re-enroll than a student who owes $100.

We also modeled these relationships among students identified by the broader literature as most likely to re-enroll.[22] This designation includes those who have been stopped out for five years or less and who earned at least 30 credits prior to stopping out. Among this population, we see similar patterns, although effect sizes among Black, Hispanic, and multi-racial students are substantially larger. Black students are between 4.5 and five percentage points more likely to re-enroll than their white peers. The coefficient for Hispanic students varies in size across model specification, but when veteran status is included as a control, Hispanic students are nearly seven percentage points more likely to re-enroll than their white peers. Among this smaller pool of students, we also note a stronger relationship between balance size and the likelihood of re-enrollment, with the likelihood increasing between one and 1.4 percentage points for every $1,000 of debt. Finally, we also find some evidence that former Pell recipients are more likely to re-enroll by roughly 2.5 percentage points.

Table 5: Predictive models of which students are most likely to re-enroll

| All Eligible Students | Recent Stopouts with 30+ Credits | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (a) | (b) | |

| Female | 0.00337 | 0.00225 | 0.00271 | -3.58e-05 |

| (0.00329) | (0.00300) | (0.0108) | (0.0106) | |

| Non-Resident Alien | -0.00148 | -0.00205 | -0.0342 | -0.0337 |

| (0.0197) | (0.0186) | (0.0886) | (0.0949) | |

| Race and Ethnicity Unknown | 0.00345 | 0.00335 | 0.0169 | 0.00570 |

| (0.00598) | (0.00572) | (0.0258) | (0.0268) | |

| Hispanic | 0.0190** | 0.00650 | 0.0662*** | 0.0319 |

| (0.00863) | (0.00701) | (0.0234) | (0.0216) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | -0.00710 | -0.00962 | -0.0230 | -0.0324 |

| (0.0213) | (0.0200) | (0.0801) | (0.0794) | |

| Asian | -0.00907 | -0.0107 | -0.0180 | -0.0277 |

| (0.0184) | (0.0176) | (0.0545) | (0.0583) | |

| Black or African American | 0.0153*** | 0.0134*** | 0.0493*** | 0.0452*** |

| (0.00368) | (0.00335) | (0.0119) | (0.0117) | |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | -0.0134 | -0.0195 | -0.0154 | -0.0264 |

| (0.0576) | (0.0500) | (0.138) | (0.105) | |

| Two or More Races | 0.0214** | 0.0254*** | 0.0325 | 0.0381* |

| (0.00961) | (0.00908) | (0.0221) | (0.0224) | |

| Pell Recipient | 0.00300 | 0.00476 | 0.0158 | 0.0248** |

| (0.00343) | (0.00317) | (0.0113) | (0.0112) | |

| Veteran | -0.00366 | -0.0134 | ||

| (0.00777) | (0.0219) | |||

| Year Since Stopout | -0.00203*** | -0.00232*** | -0.00623* | -0.00213 |

| (0.000308) | (0.000276) | (0.00345) | (0.00338) | |

| Pre-Stopout Credits | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.000201 | -0.000151 |

| (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.000147) | (0.000147) | |

| Pre-Stopout GPA | -0.00324 | -0.00293 | -0.0131 | -0.0142 |

| (0.00305) | (0.00282) | (0.0110) | (0.0110) | |

| Unpaid Balance ($100s) | 0.000759*** | 0.000688*** | 0.00104** | 0.00135*** |

| (0.000178) | (0.000164) | (0.000478) | (0.000488) | |

| Previously Enrolled in a Community College | 0.00439 | 0.00602 | 0.00887 | 0.0155 |

| (0.00408) | (0.00369) | (0.0115) | (0.0113) | |

| Constant | 0.0201* | 0.0226** | 0.0531 | 0.0402 |

| (0.0103) | (0.00964) | (0.0361) | (0.0360) | |

| Observations | 6,668 | 8,317 | 1,538 | 1,788 |

| R-squared | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.031 | 0.024 |

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Notes: Table 5 presents the findings from two specifications of this model, one including an indicator if a student is a veteran and one excluding this indicator. Because veteran status was not available for all students, we specified the model with and without this variable to test the sensitivity of the other demographic variables to the change in sample (6,668 vs 8,317 students). Non-Hispanic white students are used as a reference category for all the race and ethnicity categories.

Comparing Eligible and Non-Eligible Students

To understand how the offer of debt forgiveness relates to the likelihood of re-enrollment, we compare eligible and non-eligible students. An important aspect of eligibility is that a student cannot be in special counsel status with the OAG. This status is, predominantly, a function of the length of time between the debt being sent to the OAG and the student interacting with the OAG to determine a path towards debt resolution. These individuals meet all other requirements of the Compact described above.

Table 6 shows differences in unpaid balance size, time-since-stop-out, and available demographic information for eligible individuals and individuals who would have otherwise been eligible for the Compact in the fall 2022 semester but were assigned to a special counsel. The 5,872 students assigned to a special counsel had stopped out of school eight years ago on average, and eligible students stopped out an average of 10 years prior to the fall 2022 semester. Both groups of former students were about 40 percent male, 50 percent non-Hispanic white, and 60 percent of both groups had received Pell grants and owed debt to a two-year institution. Individuals assigned to special counsel, however, did on average have higher levels of debt. The average principal balance for students assigned to special counsel was $1,330, higher than the average balance of $1,044 for eligible students. Importantly, these differences—larger balances, fewer years since stopout, and larger shares of non-Hispanic white students—make those in special counsel more likely to participate in the Compact had they had the opportunity. This higher proclivity based on our modeling in the previous section is important for interpreting differences in re-enrollment rates presented in Table 7.

Table 6: Two sample t tests between eligible and special counsel status students

| Eligible Students (7,857) | Special Counsel Students (5,872) | Difference between groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of students | 7,857 | 5,872 | |

| Unpaid Balance Hold Size (in dollars) | $1,044.42 | $1,330.48 | $286.05*** |

| Time since stopout (in years) | 9.72 years | 7.97 years | 1.75 years*** |

| Four year institution (percent of total students) | 39% | 38% | 1 percentage point |

| Male (percent of total students) | 39% | 43% | 3 percentage points** |

| Received Pell grant (percent of total students)[23] | 61% | 59% | 2 percentage points* |

| Non-Hispanic white (percent of total students)[24] | 54% | 50% | 4 percentage points ** |

Using data from the National Student Clearinghouse retrieved by two Compact institutions, we examine the re-enrollment rates across eligible and non-eligible students to understand the relationship between eligibility and the likelihood of stopped out students re-engaging. Table 7 shows the percentage of eligible and non-eligible students who enrolled in college during the 2022-23 academic year. The enrollment rate of eligible students is 50 percent higher than that of ineligible students (six percent compared to four percent). Given the demographic differences between the groups and the associated propensities for re-enrolling under, it is likely that this is a conservative estimate of the benefit of an offer to re-enroll with the Compact. Nevertheless, these rates suggest the availability of the Compact was likely a determining factor for students’ decision to re-enroll.

Importantly, about four percent of both eligible and non-eligible students were enrolled in non-Compact institutions. This represents a substantial population of students who have moved on without being able to access their transcripts. Enrolling elsewhere suggests a commitment to furthering their education despite their debt-related challenges. Additionally, these students likely lost credits if they were unable to access their transcripts. Some of these students may have moved on to a new institution prior to the Compact forming, while others may be living outside the region and may benefit from expanded online offerings from their initial institution.

The enrollment rates are similar across the groups suggesting that there is sufficient enrollment interest in non-eligible students and had these students not been in special counsel or bankruptcy status, they could have benefited from the Compact program. We are optimistic that the Compact’s continuation may persuade some students enrolled at other institutions to enroll in participating colleges. Moreover, online learning options may make the Compact more attractive to students who have moved outside the region.

Table 7: Percent of eligible and non-eligible students who were enrolled during AY22-23

| Enrollment Status AY 2022-23 | Eligible | Not Eligible |

|---|---|---|

| Re-Enrolled | 6% | 4% |

| Enrolled at a Compact Institution | 3% | 3% |

| Enrolled at a Non-Compact Institution | 4% | 4% |

| Total Number of Students | 1,645 | 2,104 |

Short-Term Student Outcomes

Overall, students who participated in the Compact made progress towards the eventual goal of completing a credential, with seven near-completers being able to finish up their final credits and complete their degree within one or two terms. Among other things, participating students who re-enrolled needed to make academic progress and be on track with new tuition and fee payments in order to qualify for debt forgiveness.[25] Ninety-three percent of students either received debt forgiveness (66 percent) or completed part of the requirements to receive debt forgiveness (27 percent). This suggests that students who are re-enrolling under the Compact are motivated and interested in pursuing their education; however, their pathways look different. In this section we examine credit-taking pathways and short-term outcomes of students. We also model which student characteristics are associated with positive short-term outcomes.

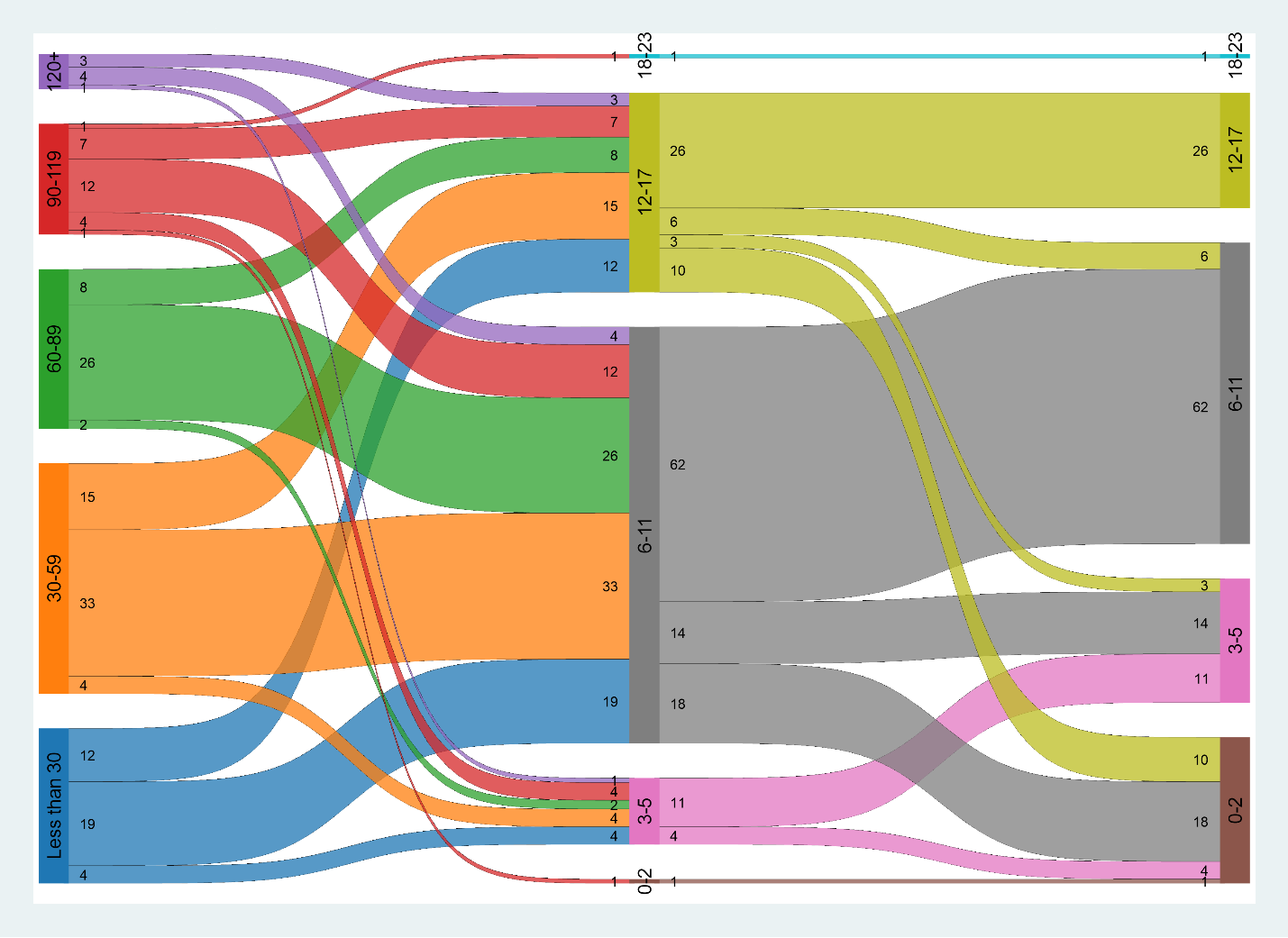

Students take a variety of pathways through their Compact experience. Figure 1 tracks students from the first semester they enter the Compact based on the number of credits they had completed prior to re-enrollment, the number of credits attempted in their first term, and the number of credits completed. The overwhelming majority of students attempted at least six credits, the minimum number required to receive forgiveness through the Compact. While 45 percent of these students completed all their attempted credits, 32 percent completed less than the required six credits (the remaining 23 percent did not complete all their credits, but completed more than six credits). This suggests that a substantial portion of students may have been ill-prepared for a heavy course load, competing life priorities and individual circumstances remain a persistent challenge for returning students, or the readjustment back to school may have been challenging. Eleven out of 15 students attempting between three and five credits completed the same number. Given the academic histories and well documented financial and personal challenges students face, allowing students to complete the number of credits for which they feel prepared may be a beneficial onramp for stopped out students seeking to return.

Figure 1: Student pathways from pre-Compact credits earned to credits attempted and credits earned

See the Appendix for a table of the student counts displayed in the figure.

See the Appendix for a table of the student counts displayed in the figure.

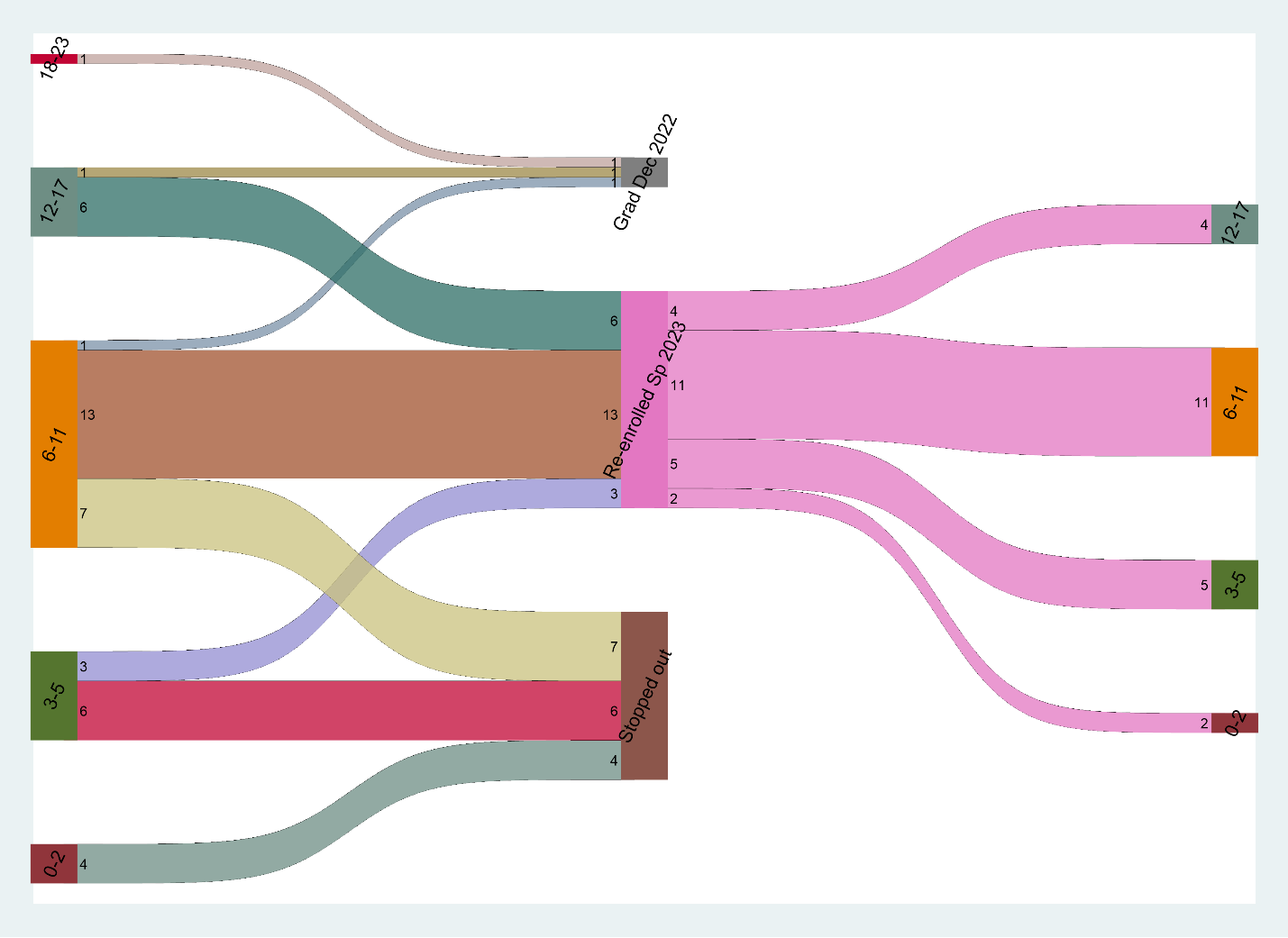

For students who first enrolled in fall 2022, we were able to track their progress into the spring term. Figure 2 shows the pathways for the 42 students who enrolled in the fall. Three of these students completed their credential during their first re-enrollment term thus turning their debt forgiveness opportunity into a pathway towards improved labor market opportunities. Seventeen of the 42 students stopped out again after the fall term. Of these repeat stopouts, 10 completed fewer than the six credits required for debt forgiveness. For these individuals, the challenges of returning to school or the failure to receive forgiveness may have served as a substantial barrier to persistence into the spring term. The remaining students qualified for debt forgiveness. While these individuals may not have persisted into the spring, they are certainly benefiting from no longer owing an institutional debt and institutions are benefiting from the tuition revenue received during the fall term. Twenty-two of the 42 students enrolled in the fall persisted into the spring term thus making additional progress towards their credential.[26]

Figure 2: Pathways of fall 2022 Compact participants

See the Appendix for a table of the student counts displayed in the figure.

We also examine which student characteristics best predict success among Compact participants. We use a linear regression model to estimate the relationship between student characteristics and key short-term outcomes including GPA (both in the first term enrolled and the average across all terms re-enrolled), credit accumulation (both in the first term and the average across all terms), credential completion, and the likelihood of meeting qualifying activities (e.g., credit and GPA requirements). As shown in Table 8, we find no significant relationships between demographics and these outcomes. This suggests that no demographic group (e.g., race/ethnicity or gender) appears to be faring better or worse while enrolled in the Compact. This parity is important when considering the potential of the Compact for addressing persisting inequities in the postsecondary sector.

We find some evidence of a relationship between the number of credits previously earned and students’ GPA and credits earned during the Compact, although two of our estimates are significant at the p<0.1 significance level. Assuming a linear relationship, for every 10 credits previously earned, a student’s GPA during the Compact increases 0.03 and the number of credits completed increases by 0.2. In other words, students who re-enrolled with more progress toward a credential were also more likely to have a higher GPA once re-enrolled. We also find evidence that higher GPAs when previously enrolled were associated with an increased likelihood that a student would meet both the GPA and credit accumulation requirements. A student with a pre-Compact GPA of 3.5 is roughly 19 percentage points more likely to meet these requirements, separately, than a student with a 2.5 pre-Compact GPA.

These findings provide important evidence of the potential success of the Compact at helping institutions and states meet equity goals and commitments. The higher success rates of students who have completed more credits and who had a higher previous GPA can help refine the definition of potential completers.[27] The NSC currently bases this designation on time since stopout and number of credits previously earned. Our findings provide supporting evidence for the number of credits earned, but also suggest that previous educational achievement may be an important factor in SCND student success. These findings can help inform outreach for the Compact and similar programs as well as broader strategies for engaging the SCND population.

Table 8: Predictive modeling of student outcomes

| Short-Term Academic Outcomes | Qualifying Activities | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average GPA | Average GPA in 1st Term Enrolled | Number of Credits Completed | Number of Credits Completed in 1st Term Enrolled | Graduated | Met Credit Requirements in 1st Term | Met GPA Requirements in 1st Term | Met Both Requirements in 1st Term | |

| Female | 0.00992 | 0.0220 | 0.393 | 0.204 | -0.0291 | -0.0487 | 0.0165 | -0.0441 |

| (0.110) | (0.110) | (0.850) | (0.874) | (0.0372) | (0.0911) | (0.0646) | (0.0924) | |

| Race and Ethnicity Unknown[28] | 0.157 | 0.163 | -0.768 | -0.717 | -0.0134 | -0.0904 | 0.147 | -0.0722 |

| (0.262) | (0.263) | (2.025) | (2.080) | (0.0886) | (0.217) | (0.154) | (0.220) | |

| Hispanic | -0.0494 | 0.0172 | -2.421 | -0.959 | 0.0113 | -0.195 | 0.126 | -0.198 |

| (0.216) | (0.217) | (1.669) | (1.715) | (0.0730) | (0.179) | (0.127) | (0.181) | |

| Black or African American | -0.0783 | -0.0749 | -0.794 | -0.900 | -0.00362 | -0.101 | -0.0605 | -0.117 |

| (0.114) | (0.114) | (0.881) | (0.905) | (0.0385) | (0.0943) | (0.0669) | (0.0957) | |

| Two or More Races | -0.0298 | -0.0296 | -1.048 | -0.817 | -0.0571 | -0.105 | -0.150 | -0.190 |

| (0.199) | (0.200) | (1.543) | (1.585) | (0.0675) | (0.165) | (0.117) | (0.168) | |

| Pell Recipient | 0.0426 | 0.00741 | -1.236 | -1.598 | -0.0511 | -0.123 | 0.0503 | -0.105 |

| (0.125) | (0.126) | (0.969) | (0.995) | (0.0424) | (0.104) | (0.0736) | (0.105) | |

| Years Since Last Enrolled | -0.00821 | -0.00811 | -0.00575 | -0.00626 | -0.00608 | 0.0142 | -0.0102 | 0.00920 |

| (0.0134) | (0.0135) | (0.104) | (0.107) | (0.00454) | (0.0111) | (0.00788) | (0.0113) | |

| Number of Credits Earned before Stopout | 0.00292* | 0.00321** | 0.0222* | 0.0207 | 0.000603 | 0.00174 | 0.00143 | 0.00148 |

| (0.00160) | (0.00161) | (0.0124) | (0.0127) | (0.000543) | (0.00133) | (0.000943) | (0.00135) | |

| GPA before Stopout | 0.785*** | 0.776*** | 1.001 | 1.001 | 0.0525 | 0.185** | 0.187*** | 0.157* |

| (0.107) | (0.107) | (0.826) | (0.848) | (0.0361) | (0.0885) | (0.0628) | (0.0898) | |

| Balance Owed ($100s) | -0.00888* | -0.00880* | 0.0406 | 0.0239 | 0.00160 | -0.000952 | -0.00637** | -0.00173 |

| (0.00520) | (0.00522) | (0.0402) | (0.0413) | (0.00176) | (0.00431) | (0.00306) | (0.00437) | |

| Previously Attended a Community College | -0.116 | -0.101 | -1.248 | -1.741* | 0.0731* | -0.192* | -0.105 | -0.196* |

| (0.130) | (0.131) | (1.009) | (1.036) | (0.0441) | (0.108) | (0.0767) | (0.110) | |

| Constant | 0.567 | 0.572 | 3.802 | 4.815* | -0.106 | 0.287 | 0.457** | 0.392 |

| (0.358) | (0.359) | (2.767) | (2.842) | (0.121) | (0.296) | (0.210) | (0.301) | |

| Observations | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| R-squared | 0.332 | 0.328 | 0.124 | 0.115 | 0.076 | 0.113 | 0.175 | 0.097 |

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Conclusion

We shared our evaluation findings with the implementation team throughout the pilot year in an effort to inform real-time adjustments. Our evaluation continued after the pilot year and included additional data collected from institutions on short-term outcomes. This report is the culmination of the quantitative evaluation efforts and includes several recommendations noted throughout. Here we summarize the key recommendations stakeholders should consider as they continue the Compact’s work as well as implications for broader efforts to re-engage SCND students.

The success of students who re-enroll in the program underscores the substantial barrier that institutional debt and transcript holds create for students. When these barriers are removed, students re-enroll, earn additional postsecondary credits, and complete credentials. While this evaluation only assesses an initial pilot year, debt forgiveness had an immediate impact and resulted in several students earning a postsecondary credential within one semester. Moreover, the high rates of persistence for students who enrolled in the fall and the significant number of students taking a full courseload highlights the revenue benefits for institutions that are forgiving balances of less than $1,500 (the average balance for re-enrolled students).

Students of color and lower income students are more likely to have institutional debts and be classified as SCND. However, the parity in short-term outcomes of these groups, as compared to their whiter and wealthier peers, demonstrates the Compact’s effectiveness at addressing postsecondary inequities. By removing the hurdle of institutional debts, the Compact can help institutions fulfill equity-related aspects of their mission and can help states meet equity goals. Moreover, previous research has shown the importance of engaging SCND students and students of color if states are to meet ambitious attainment goals,[29] and addressing institutional debts appears to be a proactive approach to meeting these goals.

Recommendations

Given the increased likelihood of historically underserved groups to participate in the Compact, as well as to owe institutional debts, we recommend targeted outreach to these groups in order to increase opportunity for them and to maximize the impact of the Compact. Additionally, the near-term success of students with larger credit accumulation and high GPAs pre-stopout suggests outreach efforts could be improved with an expansion of the definition of likely completers. Of course, we recommend all students be eligible for the opportunity, however, when facing resource constraints, institutions can likely maximize returns on outreach spending by targeting these groups with higher likelihoods of re-enrolling and succeeding in the program.

We also suggest pairing the Compact, and other debt forgiveness programs, with access to wraparound services. Students returning to school face a broad range of challenges and providing additional wraparound support is likely to maximize the benefits. Our findings suggests that students who have faced systemic hurdles in and out of the education system (e.g., lower-income students and students of color) are more likely to re-enroll when offered a solution to their institutional debt and, despite the systemic barrier, have short-term academic outcomes on par with their peers. Previous survey findings also suggest that SCND students with institutional debts are struggling with food and housing insecurity and general financial constraints.[30] As such, we recommend that institutions coordinate offices and services, including non-institutional sources (e.g., SNAP), and direct Compact participants or would-be participants to these coordinators so students can easily access these. Understanding what is available may be an important factor as students consider returning.

Finally, we recommend continued evaluation of the Compact and similar programs. Given that this report includes findings from the Compact’s pilot year, it is important to continue evaluation efforts. Pilot years frequently include hurdles and complications atypical to future years of implementation that result from multiple stakeholders coordinating on a new program. Our evaluation process was iterative and included continuous feedback, of both the quantitative and qualitative elements of the evaluation, to the implementation team in an effort to bring research to practice immediately. This approach has resulted in the Compact adjusting its approach during the second year of implementation to include new outreach procedures, changes to administrative processes, and adjusting qualifying activities to better reflect students’ needs. Continued evaluation efforts will help understand how the evolving nature of the Compact impacts its efficacy. Continued evaluation will also allow for the assessment of longer-term student outcomes and program efficacy.[31] We also encourage the evaluation of similar debt forgiveness programs. Context is a critical component of any program’s success. It is important that the continued evaluation of the Compact as well as the evaluation of similar programs do so in a way that reflects the context in which the programs operate and thus mediate and moderate outcomes and program efficacy.

Appendix: Student counts in figures 1 and 2

Figure 1: Student pathways from pre-Compact credits earned to credits attempted and credits earned

| Pre-Compact Credits Earned | First Compact Term Credits Attempted | First Compact Term Credits Completed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of credits | # of students | # of credits | # of students | # of credits | # of students |

| 120+ | 8 | 18-23 | 1 | 18-23 | 1 |

| 90-119 | 25 | 12-17 | 45 | 12-17 | 26 |

| 60-89 | 36 | 6-11 | 94 | 6-11 | 68 |

| 30-59 | 52 | 3-5 | 15 | 3-5 | 28 |

| <30 | 35 | 0-2 | 1 | 0-2 | 33 |

Figure 2: Pathways of fall 2022 Compact participants

| Fall 2022 Credits Completed | Fall 2022 Outcome | Spring 2023 Credits Completed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of credits | # of students | # of credits | # of students | ||

| 18-23 | 1 | Graduated December 2022 | 3 | 12-17 | 4 |

| 12-17 | 7 | Re-enrolled Spring 2023 | 22 | 6-11 | 11 |

| 6-11 | 21 | Stopped out | 17 | 3-5 | 5 |

| 3-5 | 9 | 0-2 | 2 |

||

| 0-1 | 4 | ||||

Endnotes

- Pooja Patel and James Dean Ward, “Institutional Supports for Students with Stranded Credits: Survey Results from the Ohio College Comeback Compact,” Ithaka S+R, 9 November 2023, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.319890. ↑

- Julia Karon, James Dean Ward, Catharine B. Hill, and Martin Kurzweil, “Solving Stranded Credits: Assessing the Scope and Effects of Transcript Withholding on Students, States, and Institutions,” Ithaka S+R, 5 October 2020, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.313978. ↑

- Alessandra Cipriani-Detres and Sarah Pingel, “Stranded Credits: State-Level Actions and Opportunities,” Ithaka S+R, 15 August 2022, https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/stranded-credits-state-level-actions/. ↑

- Sarah Pingel, “Lost and Found: State and Institutional Actions to Resolve Stranded Credits,” Ithaka S+R, 7 July 2022, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.316883. ↑

- Piet van Lier, “Collecting Against the Future,” Policy Matters Ohio, February 2020, https://www.policymattersohio.org/files/research/collectagainstfuture1.pdf. ↑

- Martin Kurzweil, Elizabeth Looker, and Brittany Pearce, “After Successful Pilot, the Ohio College Comeback Compact Moves to Full Implementation,” Ithaka S+R, 27 September, 2023, https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/after-successful-pilot-the-ohio-college-comeback-compact-moves-to-full-implementation/. ↑

- Although not a formal requirement, the process the OAG used to check for special counsel and bankruptcy status restricted eligibility to only individuals with Social Security numbers in their student records. ↑

- Some students who did not have their debt certified with the OAG were allowed to participate in the Compact after investigations into the data could not produce a logical reason for the debt not being certified, at no fault of the student. ↑

- Special counsel status refers to when the OAG assigns cases to third-party vendors or lawyers to pursue collections. ↑

- A report of student survey findings can be found here: Pooja Patel and James Dean Ward, “Institutional Supports for Students with Stranded Credits: Survey Results from the Ohio College Comeback Compact,” Ithaka S+R, 9 November 2023, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.319890. An additional report summarizing qualitative evaluation findings is available here: Pooja Patel, Sosanya Jones, and James Dean Ward, “Second Chances: A Qualitative Assessment of the Ohio College Comeback Compact,” Ithaka S+R, 9 May 2024, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.320667. ↑

- To determine eligibility for the Compact, the implementation team at Ithaka S+R collected lists from each institution of students who met the time-since-stop-out and GPA requirements. The team identified 15,068 students as eligible for the Compact prior to applying eligibility data from the OAG. With data provided by the OAG, the implementation team identified students who were ineligible for the Compact due to owing debt to multiple institutions, being in bankruptcy proceedings, and/or being in special counsel status. The OAG was able to find a record of 13,090 of the 15,068 students. Seven individuals had principal balances of more than $5,000 in their accounts with the OAG, a difference from their institutions’ records. Forty-two individuals were ineligible due to being in bankruptcy proceedings, and 217 individuals were ineligible due to owing debt to multiple schools. Special counsel (i.e. third-party vendors or lawyers appointed by the OAG) status had the largest impact on eligibility: 5,872 former students, or 45 percent of the records identified by the OAG, had debt assigned to a special counsel and were not eligible to participate in the Compact. An additional 1,073 individuals were ineligible due some combination of bankruptcy, special counsel, or owing debt to multiple schools. In total, 7,211 students were ineligible due to information in their OAG records. Finally, the 1,978 students who did not have an OAG record but were otherwise eligible were allowed to participate. This resulted in a final eligibility list for the fall 2022 semester of 7,857 students. An additional 1,252 students became eligible in the spring 2023 semester, for a total of 9,109 eligible students in the pilot year. ↑

- Institutions have inconsistencies in how they have collected gender over the years. As such, there is little representation in the data provided by institutions of other genders. ↑

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, “Some College, No Credential Student Outcomes Annual Progress Report – Academic Year 2021/22,” April 2023, https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SCNCReport2023.pdf. ↑

- Pooja Patel and James Dean Ward, “Institutional Supports for Students with Stranded Credits: Survey Results from the Ohio College Comeback Compact,” Ithaka S+R, 9 November 2023, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.319890. ↑

- We use non-Hispanic, white students as the reference category throughout our analysis to understand equity implications and because these students are the largest group in our sample. ↑

- Sosanya Jones and Melody Andrews, “Stranded Credits: A Matter of Equity. Research Report,” Ithaka S+R, 17 August 2021, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.315765; Bradley R. Curs, Casandra E. Harper, and Justin Kumbal, “Institutional Inequities in the Prevalence of Registration Sanctions at a Flagship Public University,” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education (2022), https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/dhe0000432. ↑

- People of color: Non-Resident Alien, Hispanic, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Haiwaiian or Pacific Islander, Two or More Races. ↑

- J. Causey, A. Gardner, A. Pevitz, M. Ryu, and D. Shapiro, Some College, No Credential Student Outcomes, Annual Progress Report – Academic Year 2021/22(April 2023), Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SCNCReport2023.pdf; “Data on Borrowers in Default,”https://www2.ed.gov/policy/highered/reg/hearulemaking/2023/data-on-borrowers-in-default.pdf; Urvi Neelakantan, “Black-White Differences in Student Loan Default Rates Among College Graduates,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 23-12, April 2023, https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/economic_brief/2023/eb_23-12. ↑

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, “Some College, No Credential Student Outcomes Annual Progress Report – Academic Year 2021/22,” April 2023, https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SCNCReport2023.pdf. ↑

- We also fit logistic regression models as a robustness check but present the linear probability models because of their ease of interpretation. ↑

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, “Some College, No Credential Student Outcomes Annual Progress Report – Academic Year 2021/22,” April 2023, https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SCNCReport2023.pdf. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Omits 1,622 observations with missing values for the Pell grant variable. ↑

- Omits 1,272 observations with missing values for the race/ethnicity variable ↑

- To qualify for debt forgiveness in the pilot year, eligible students must have signed the Compact permission form, the Compact participation form, been accepted by an institution participating in the Compact, met with an advisor prior to enrolling and twice throughout the academic term, completed a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) form, and paid tuition and fees in full or agreed to and bene in compliance with a payment plan. Students must have also earned six credits towards a degree or certificate program in the academic semester. Completion of all activities for one term qualified the student for up to $2,500 in debt reduction, completion of all activities in a second consecutive term (minus activities already completed—the participation and permission forms, pre-enrollment advising, and completing the FAFSA) qualified the student for an additional $2,500 in debt reduction. If a student completed qualifying activities and a degree or certificate program in one semester, they qualified for the full $5,000 in debt reduction. Some flexibility with credit requirements was built into the Compact, such as if a student needed fewer than six credits to graduate, and some institutions waived requirements related to signing participation or permission forms by specific deadline in an effort to maximize the benefits of the program. ↑

- The evaluation team is continuing to monitor the pathways of Compact participants into the second year of the program. ↑

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, “Some College, No Credential Student Outcomes Annual Progress Report – Academic Year 2021/22,” April 2023, https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SCNCReport2023.pdf. ↑

- Non-Hispanic white students are the reference category for all race/ethnicity categories. ↑

- James Dean Ward, Jesse Margolis, Benjamin Weintraut, and Elizabeth D. Pisacreta, “Raising the Bar: What States Need to Do to Hit Their Ambitious Higher Education Attainment Goals,” Ithaka S+R, 13 February 2020. https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.312647. ↑

- Pooja Patel and James Dean Ward, “Institutional Supports for Students with Stranded Credits: Survey Results from the Ohio College Comeback Compact,” Ithaka S+R, 9 November 2023, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.319890. ↑

- Ithaka S+R is currently continuing evaluation efforts in the second year of the program. ↑