Security and Censorship

A Comparative Analysis of State Department of Corrections Media Review Policies

-

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Key Findings

- Introduction

- Methods

- Policy, Censorship, and Security

- Content-Neutral Prohibitions

- Content-Based Prohibitions

- Justifications of Inspection and Censorship

- Content Protections

- Publication Review and Censorship Appeals

- Recommendations

- Special Thanks

- Appendix: Model Media Review Policy

- Appendix 2: The Role of the Courts in Shaping Media Review Policy

- Endnotes

- Executive Summary

- Key Findings

- Introduction

- Methods

- Policy, Censorship, and Security

- Content-Neutral Prohibitions

- Content-Based Prohibitions

- Justifications of Inspection and Censorship

- Content Protections

- Publication Review and Censorship Appeals

- Recommendations

- Special Thanks

- Appendix: Model Media Review Policy

- Appendix 2: The Role of the Courts in Shaping Media Review Policy

- Endnotes

Executive Summary

Despite resurgent public interest in censorship issues, research and reporting on prison censorship policies remain largely localized, with few wide-scale, systematic studies of the issue. There is good reason for this: the highly decentralized nature of the carceral system in the United States and the practical challenges in discovering and navigating correctional policy documentation complicate such an undertaking. In an effort to make available policy information more accessible, to better understand the national landscape of prison censorship policy, and to develop a sense of how censorship policies might impact higher education in prisons, Ithaka S+R examined media review directives across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. This research was made possible with grant funding provided by Ascendium Education Group and is one facet of a larger study of technology and censorship in higher education in prisons.[1] It is our hope that the findings will be of interest to state Departments of Correction (DOC), as well as researchers and advocates.

Key Findings

- Key terms and language are common across DOC censorship policies, but the policies and procedures related to them differ greatly across states.

- Forty-two of 51 media review directives limit the vendors from which materials can be purchased.

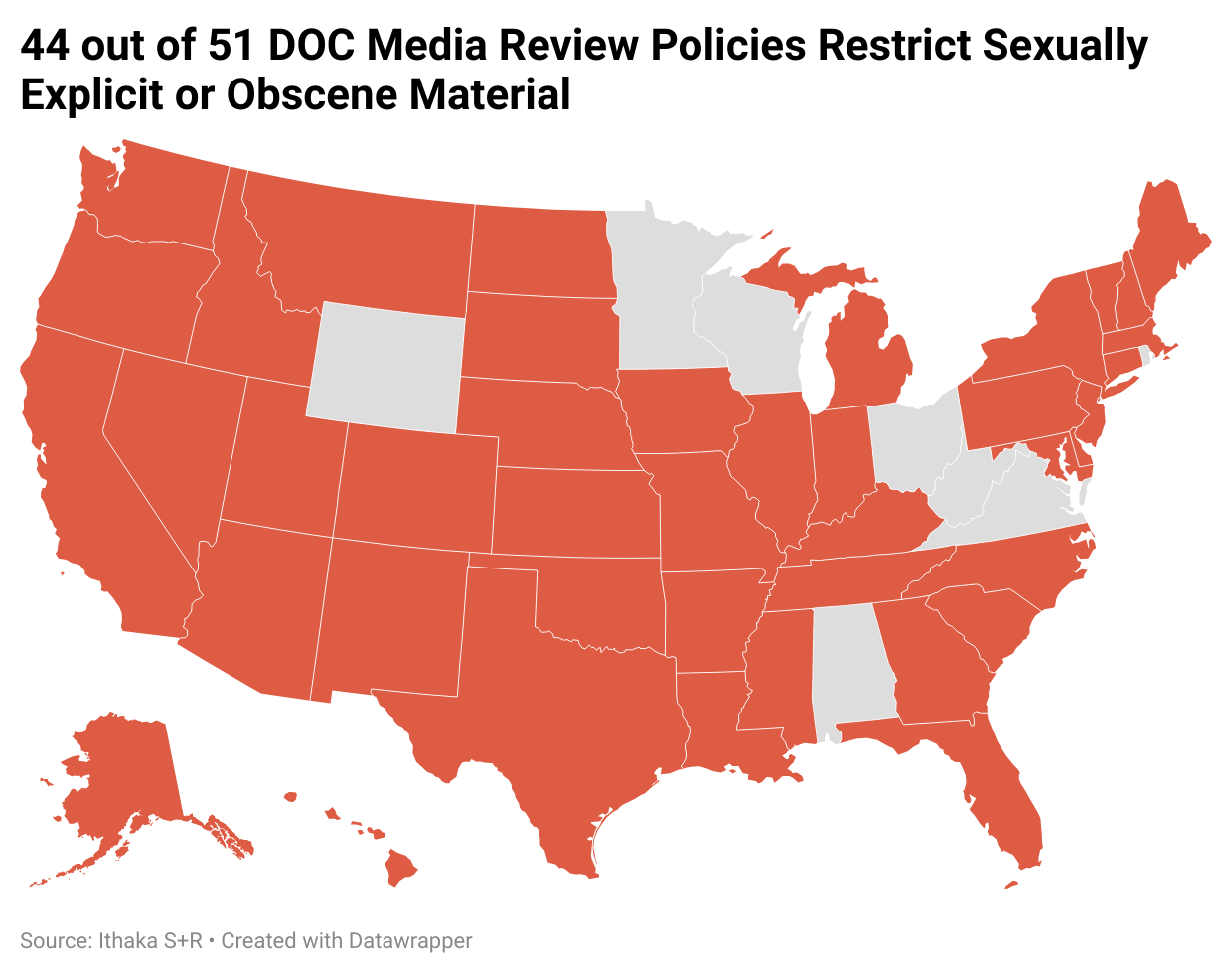

- Forty-four of 51 media review directives have clauses addressing and limiting access to sexually explicit or obscene content.

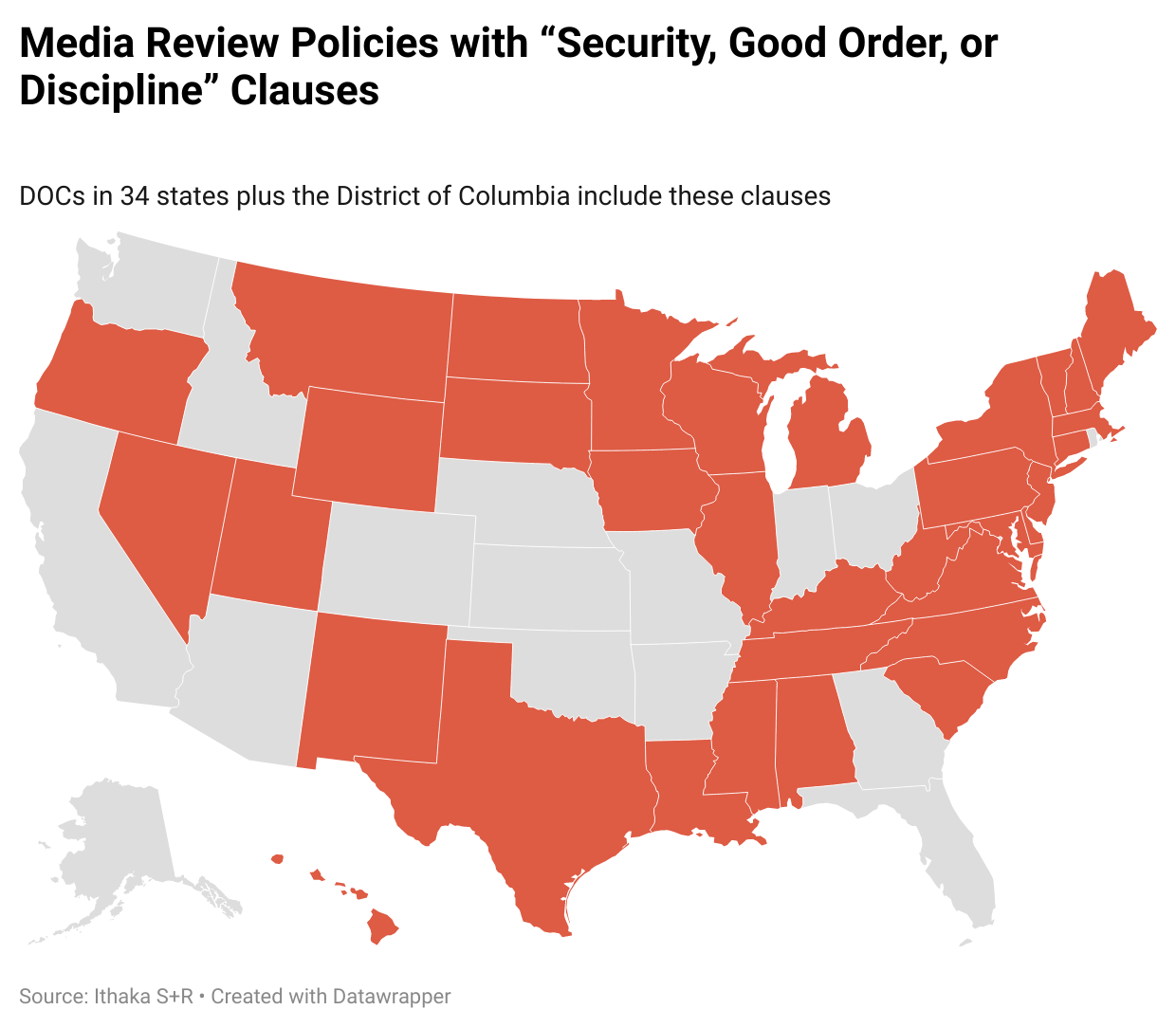

- The legal power of DOC to surveil and censor is grounded in the protection of “security, good order, or discipline.” As a result, variations on this terminology are present in 35 of 51 media review directives. In practice, the term frequently serves as a catchall, providing broad latitude and powers for censorship.

- Content protection clauses or carve outs exist. Such provisions allow access to publications which might otherwise be censored; however, their application appears very narrow and restricted.

- Publication review and censorship appeals processes are addressed to some extent in nearly all policies, but appeals processes often inequitably burden people who are incarcerated.

Introduction

Prison censorship policies serve as a focal point for organizations dedicated to protecting freedom of speech, and stories of arbitrary or unexpected censorship have occasionally gone viral. However, very few systematic explorations of prison censorship policy and practice exist.[2] This is due in no small part to the complex nature of correctional policy and implementation in the US: each state as well as the federal government structure and govern their own correctional systems, with separate policies, procedures, and structures. While understanding how prison censorship practices might limit individual access to materials that could promote personal growth, intellectual development, or rehabilitation is an important endeavor in its own right. The imminent reinstatement of federal Pell grant funding for students who are incarcerated has made it all the more imperative to understand how prison censorship practices intersect with intellectual freedom and educational equity.[3] As part of Ithaka S+R’s ongoing study of the relationship between technology and self-censorship in higher education in prison, we undertook a scan of prison media review guidelines from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. This project was made possible with grant funding provided by Ascendium Education Group.

Prison media review policies set forth institutional standards for evaluating what incarcerated people can read, and in some cases correspond about, listen to, and watch. By extension, these policies also directly influence the content of prison library collections, the texts that readers on the inside can purchase or be gifted, and, in some cases, the texts that instructors can bring into the facility to teach with. In practice, the extent to which higher education in prison programs are governed by these policies varies widely, as will be explored in Ithaka S+R’s forthcoming (2023) report on self-censorship. This is unsurprising given that existing policies were not designed to account for the needs of college level programming, which, unlike secondary education, is provided by external higher education institutions rather than by dedicated education staff within the correctional system.

Additionally, such policies are not designed to account for the increased complexity and variability in postsecondary educational structures and programming. Unlike secondary education, which is highly regulated and designed to meet fairly specific national and state standards, the texts, topics, and assignments in higher education instruction are characterized by mutability and individuality. Moreover, because they introduce students to expert perspectives and methods, higher educational offerings frequently rely on developing critical thinking skills and engaging in contentious issues. Thus, courses might potentially require students to engage in debates, to collaborate in research, and to critically examine materials that might be censored in carceral contexts.

Media review policies can have a chilling effect on speech and academic inquiry, even in cases where programs are not entirely subject to the media review process outlined in Department of Corrections (DOC) policy.[4] This report charts the evolution of DOC media review policies in response to legal decisions, notes significant findings across the current landscape of media review directives, and proposes new policy language and procedures to minimize censorship and expand access for incarcerated college students.

Strengthening the foundation of these policies is all the more pressing, given major shifts in the role of technology in the field. Strengthening policies to protect the rights of people who are incarcerated and establish clearer guidelines for practice can help to streamline the integration of new technologies and applications. Over the last handful of years, an increasing number of states have implemented mail digitization policies, for example. These policies are often enacted through addendums or policy announcements, rather than through the adjustment of formal media or mail review directives, and they are difficult to track, though Prison Policy Initiative estimates that “at least thirteen states” have enacted mail scanning policies.[5] The publicly stated justification for mail digitization policies dates back to an outbreak of illness at a Pennsylvania prison center that was initially thought to be related to contraband exposure in mail processing, though medical testing did not find that to be the cause.[6] Such policies are also directly tied to service agreements with for-profit prison telecom companies, such as Smart Communications and Securus/JPay. Rather than having prison staff sort, screen, review, and deliver mail, this process is outsourced to contractors.[7] This, in turn, may be seen as one of several emergent technological attempts to ameliorate understaffing issues. It is not the only such attempt, as Nevada’s recent plan to resolve understaffing issues with ankle monitors and drones emphasizes.[8] Moreover, with Pell restoration on the horizon, security-minded technology companies that already work with DOCs are rapidly moving into the educational sphere. Considered alongside the ever-growing prevalence of tablets for media consumption and self-education inside the prison system, it is clear that technological changes are already complicating the media review landscape, censorship, and self-censorship. The profound effects of these changes on people in prisons’ access to information require proactive policy interventions.

Understanding exactly what types of media and which individual titles are being censored is therefore an important task, and one that can obliquely reveal systematic trends, injustices, or inequalities. In this report, however, we take a different approach by examining the landscape of media review directives across states in order to identify the common policies, logics, and rationales behind censorship in a correctional environment. Rather than call attention to individual instances of censorship, we seek to document the underlying systems that give rise to these individual instances.

Methods

Ithaka S+R gathered relevant policies from all 50 states and Washington DC as well as related supplemental documentation from ten states. To do so, we began by searching for publication review directives and procedures by state. While most contemporary media review directives are available online directly from the relevant state or DOC, the way they are housed and retrieved varies widely. Media review policies may be found within documents that are variously codified as handbooks, regulations, rules, directives, policy, or procedures. Relevant information about how media is reviewed may be found under rules and regulations about mail, correspondence, or publications, which also complicates source discovery. In some cases, relevant policy is divided across or supplemented by additional documents. Relevant documents from the Arkansas DOC illustrate the point: information about media review and censorship is spread across three documents—one addressing administrative rules for publications, another providing an administrative directive addressing procedures for enforcing the administrative rules, and a third covering the rules for correspondence.[9] The full picture of how Arkansas’s media review policy is structured and enacted can only be seen once these disparate documents are retrieved and consulted in tandem. In some cases, policies also reference attachments or addendums, which are seldom easily discoverable. Where possible, Ithaka S+R also retrieved and consulted items listed in appendices, such as the Maine DOC’s “Approved Book Distributors” document. Retrieving policy sets is further complicated by the way files are named, organized, and archived, which differs from state to state.

After compiling a sample of 62 documents consisting of the most up-to-date media review policies and relevant additional files available for all 50 states and the District of Columbia,[10] the files were coded for analysis in NVivo. Using a grounded approach, we developed our set of codes—which function as thematic or formal content tags—as we examined files, based on the common language, policies, and procedures in the source documents. After trends began to appear, keyword searches were conducted across the entire data set to explore specific topics in greater depth. This process demonstrated the presence of shared language across policies, which was then examined in context. Once initial coding was completed, we began to trace the relevant legal case history, and used concepts and terms from that history to help refine and group codes. A second coding pass was then completed, and common types of censorship were noted by frequency. A third coding pass searching specifically for terms and policies related to these common types of censorship was then completed.

Current debates surrounding censorship in prisons, and the function of both content-based and content-neutral prohibitions in that process, informed attention to significant themes surrounding some specific language and prohibitions—such as the prevalence of catchall phrases harking to the legal history outlined in Appendix 2. Because some media review policies deal with correspondence and publications in the same directive, and titles and sections vary widely, all files were reviewed in full, despite the study’s limited focus on publication and media review. In addition to tracking keywords and structures that appeared regularly across documents, policies that appeared particularly singular or unique were also noted.

Policy, Censorship, and Security

The tension between protecting the rights of people who are incarcerated and maintaining the broad powers of prison administrators to ensure safety is a defining characteristic of the legal history establishing media review and censorship powers.[11] The legal history outlined in detail in Appendix 2 traces how the balance between individual rights and correctional security has shifted through three phases: the first, favoring security; the second favoring individual rights, and the third returning favor to correctional security.[12] Rather than advocating for a shift in one direction or another, we contend that refiguring the relationship between information and education, and censorship and security holds the key to improving both the experiences and outcomes of people who are incarcerated. Our examination of the judicial history establishing and redefining the limits of prison censorship powers revealed two key points necessary for understanding the current landscape of media review directives. First, much of the common, broad language in media review directives is drawn directly from federal legal decisions that established or elaborated upon censorship powers relevant to the prison system. And second, the tension between personal rights and correctional security that characterizes media review directives cannot simply be defined away but must be addressed through systemic adjustment. The legal framework that underlies present DOC media review policies is important to note because, though DOCs execute and enforce these policies, the terms on which they do so, and the level of discretion afforded to them, has been largely defined by the courts. As this report demonstrates, while the extremely broad and general nature of “security, good order, or discipline” and related clauses enable arbitrary enforcement and sweeping systematic rejections, there is room within the current framework to strengthen and improve policy to better enable access.

The legal history demonstrates that narrowing definitions or reframing policy limits in and of themselves will not resolve the conflict set up between institutional security and individual rights. These issues cut across all of the media review policies we studied and arise in relation to myriad aspects of media review policy and procedure. It is our contention that examining how individual rights and security interact within and across the media review landscape can help us to reframe their relationship. Rather than seeing individual rights and education as threats to security, a more holistic approach would consider individual rights and education as constructive factors that promote security and can increase the safety and wellbeing of everyone in the facility.[13] Our study focuses on specific aspects of media review policy, examining content-neutral prohibitions, content-based prohibitions, justifications for publication inspection and censorship, content protections, and censorship review and appeals processes.

Content-Neutral Prohibitions

PEN America’s “Literature Locked Up” defined and examined two categories of rules governing media review and censorship in prisons: content-based and content-neutral prohibitions.[14] Here we focus on some of the most prevalent content-neutral prohibitions found in media review directives. It is also important to note that while content-based and content-neutral prohibitions can be separated categorically, the compounded effects of their interactions can have deep ramifications and are not always immediately apparent.

The most prevalent content-neutral prohibitions involve limitations on where and how people who are incarcerated may purchase books. Forty-two of 51 DOC policies have a clause limiting the purchase or receipt of publications to some combination of publishers or verified distributors (see Figure 1). The intention of these policies appears to be to streamline mailroom procedures and limit the possibility that contraband might be smuggled into facilities. The majority of these policies are very brief and direct, such as Alabama’s: “The publications should be received directly from the publisher or a recognized distributor.”[15] While this seems straightforward, complications arise in determining which vendors or distributors are “approved” or “recognized,” and, in practice, these policies can limit what books can be purchased, increase costs, or prohibit the donation or gifting of books. Take for example, the Connecticut DOC’s policy, which states: “An inmate may order books in new condition only from a publisher, book club, or book store.”[16] At first glance, this policy appears more lenient than others which require an approval process for verified distributors, however, the policy eliminates the availability of used books and limits the marketplaces where books can be purchased by or for people incarcerated in Connecticut, ultimately increasing costs.[17]

Figure 1

While limitations on vendors and markets serve as widespread and restrictive content-neutral prohibitions, there are a variety of other policies that, when considered in the broader ecosystem of prohibitions, may have far reaching impacts, such as limitations on the dimensions, number, binding, or cover of publications, with bans on hardcover books being particularly common. The ban on hardcover books might seem likely to cause only minor inconvenience; however, when considered in tandem with other content neutral prohibitions, such bans can become costly or restrictive, especially for students or the college in prison programs that seek to serve them. Many college textbooks used in science, technology, engineering, mathematics (STEM) and the social sciences come in large dimensions, may be hardbound, and may even be customized for a particular college or university, and they frequently cost $100-$200 when purchased. These textbook costs can strain already tight higher ed in prison program budgets or serve as added constraints on courses taught. Given the combination of content-neutral restrictions that may be in effect—such as bans on secondhand, large, oversized, or hardbound books; publisher or verified distributor limitations; and property or storage limits—these programs may be unable to obtain a copy that meets all of the DOC’s restrictions. And, while many programs work closely and cooperatively with their DOC or facility, these limitations create additional costs, burdens, and challenges in obtaining, storing, and ensuring student access to publications needed for their education.

There can also be additional, complicating factors based on how other policies interact with approved vendor lists or limitations on the number of packages individuals may receive or books they may purchase. For example, in the policy of the Tennessee DOC, there is both a limited list of approved contract vendors, greatly limiting publication options and availability, and a policy limiting individuals “convicted of a disciplinary offense” from receiving any materials, with the exception of clothing, for extended periods of time.[18] This example illustrates how these prohibitions can act together to make publications and educational resources practically unobtainable in some contexts. It is beyond the scope of this study to examine the intersections and interactions of all content-neutral prohibitions in place in each state; however, such prohibitions can have profound interactions and are worthy of more extensive research.

Content-Based Prohibitions

A broad range of content-based prohibitions are prevalent across media review directives. Two of the most commonly occurring are analyzed below: those blocking material that is considered sexually explicit, obscene, or containing nudity, and those addressing non-English language material and material in code. More than half of the 51 DOC media review directives we analyzed include these types of content-based prohibitions. While lay audiences may struggle to see the logic behind these policies, it is important to note that, currently, censorship of sexually explicit materials is tied to protecting those working and residing in prisons from sexual harassment. Censoring material in code and non-English language material is framed as a security measure to limit the possibility that people who are incarcerated can communicate without DOC or facility staff oversight. That being said, in practice these policies disproportionately impact the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) community and non-English speaking communities. They may implicitly, and in rare cases explicitly, sanction discriminatory prohibition against these communities, while at the same time limiting what can be taught in higher education programs.

Sexually Explicit Material, Obscene Material, and Nudity

Most DOCs prohibit publications containing sexually explicit material (see Figure 2).[19] Twenty-nine DOCs define “sexually explicit” to include any materials depicting nudity, such as Idaho’s policy which states that “[s]exually explicit and pornographic material includes pictorial depictions of nudity” and Louisiana’s which includes material with “detailed verbal descriptions or narrative accounts,” as well.[20] These policies appear at times extraordinarily sweeping, such as in Georgia’s:

Sexually Explicit Material: Pictures, publications, and materials featuring nudity or sexually explicit conduct. Nudity is defined as a pictorial depiction where the human male or female genitals, pubic area, buttocks, or male or female breasts are exposed. Sexually explicit conduct is a written or pictorial depiction of actual or simulated sexual acts, including, but not limited to, intercourse, sodomy (oral or anal) or masturbation.[21]

This example demonstrates an expansive understanding of sexually explicit material, one which encompasses nudity and written descriptions or depictions of “actual or simulated sexual acts.” This effectively bans any material with nudity or sexual content of any nature and could limit what types of materials could be taught in an art or literature class, to give just two examples.[22]

Across policies, media directives demonstrate a variety of different ways of classifying or categorizing material featuring nudity, sexually explicit content, or obscene content, that amount to the same effect: censoring it. The California DOC’s policy provides an example with different categories that function to the same effect: nudity and sexually explicit content have separate definitions, but are both banned under the umbrella of “obscene material.”[23] Similarly, Utah’s policy does not define nudity as sexually explicit, but prohibits it anyway in the same clause.[24] In short, a variety of terms and classifications are used to enact what are in practice the same content bans. While such censorship may be necessary in relation to the well-being and rehabilitation of individuals charged with sex-related crimes, the prohibition of such materials writ-large merits greater scrutiny. This censorship has the potential to restrict educational materials that feature sexually explicit material, nudity, or even a sex scene, unless the work in question is singled out and protected as educationally or culturally valuable. We address such “educational content protections” in more detail in the section titled “Content Protections.”

Figure 2

Despite the broad language and far-reaching censorship implied in sexually explicit materials bans, a number of DOCs have policies that do not entirely prohibit material that contains nudity or is deemed sexually explicit or obscene.[25] Instead, these states include exception clauses that leave determinations up to staff judgment of the merit or value of a given work. For example, North Dakota’s directive states that “[s]exually explicit material does not include material of a news or information type,” although, what makes something material of a news or information type is not defined in the directive.[26] Pennsylvania’s directive, on the other hand, is considerably more liberal in its determination and more precise in its definitions. While sexually explicit and obscene materials are both banned in the policy, they are defined separately, in detail. Moreover, the Pennsylvania directive contains a unique, guiding policy:

The below listed considerations will guide the Department in determining whether to permit nudity, explicit sexual material, or obscene material:

- is the material in question contained in a publication that regularly features sexually explicit content intended to raise levels of sexual arousal or to provide sexual gratification, or both? If so, the publication will be denied for inmate possession; or

- is it likely that the content in question was published or provided with the primary intention to raise levels of sexual arousal or to provide sexual gratification, or both? If so, the publication or content will be denied for inmate possession.[27]

This policy is unique in that it foregrounds the possibility that publications featuring nudity, explicit sexual material, or obscene material may be allowable. It is also a rare example where policy utilizes guiding questions as guardrails to limit subjective or sweeping interpretations of censorship rules. Moreover, Pennsylvania’s directive defines both explicit sexual content and obscene material at some length.[28]

Another feature unique to Pennsylvania’s directive is that it clearly defines “prurient interest,” in relation to its obscenity censorship. This is noteworthy because “prurient interest” plays a prominent role in the history of censorship in the United States and this example again shows the intersection of legal precedent and DOC censorship policy.[29] “Prurient interest” is defined as “material having a tendency to excite lustful thoughts” in footnote 20 the 1957 Supreme Court decision, Roth v. United States (1957).[30] The use of this term is particularly important in the context of censorship issues, as Roth noted that “sex and obscenity are not synonymous,” and “[o]bscene material is material which deals with sex in a manner appealing to prurient interest.”[31] Given the echoes of judicial decisions in media review policies, it is perhaps unsurprising that the censorship policies of media review directives, which deal directly with the mailing of publications and other materials, would draw on related legal precedent. If we extend our view to not just the definition of prurient interest, but its application and determination in Roth and subsequent, related case law, we find that there are echoes of this language in almost all DOC directives that have sexually explicit material prohibitions. [32]

A small minority of DOCs define “sexually explicit” even more broadly, with Mississippi extending the category to include books depicting “simulated homosexual activity.”[33] Louisiana, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina all expressly ban any literature that depicts homosexuality.[34] Furthermore, states that do not have explicit bans on literature with depictions of homosexuality reportedly have histories of implicitly enacting such bans in practice, if not policy. For instance, in 2019 Book Riot reported that New Hampshire banned a 2015 research report by the group Black and Pink, which studied the experiences of LGBTQ people in the prison system.[35] The report was banned with the justification that it depicted “unlawful sexual practice,” presumably because it provided information on the disproportionately high rate at which LGBTQ individuals were assaulted while in prison.[36] There are other examples. Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, a guidebook to help trans and nonbinary individuals find resources and articulate their own identity, was banned in prisons in at least seven states and the award winning graphic novel Fun Home, a queer coming-of-age story, was banned in Texas.[37] Considered together, these examples demonstrate how sexually explicit content policies may limit the availability of cultural productions by, for, and about LGBTQ people, despite the fact that the policy is designed to address something else altogether.

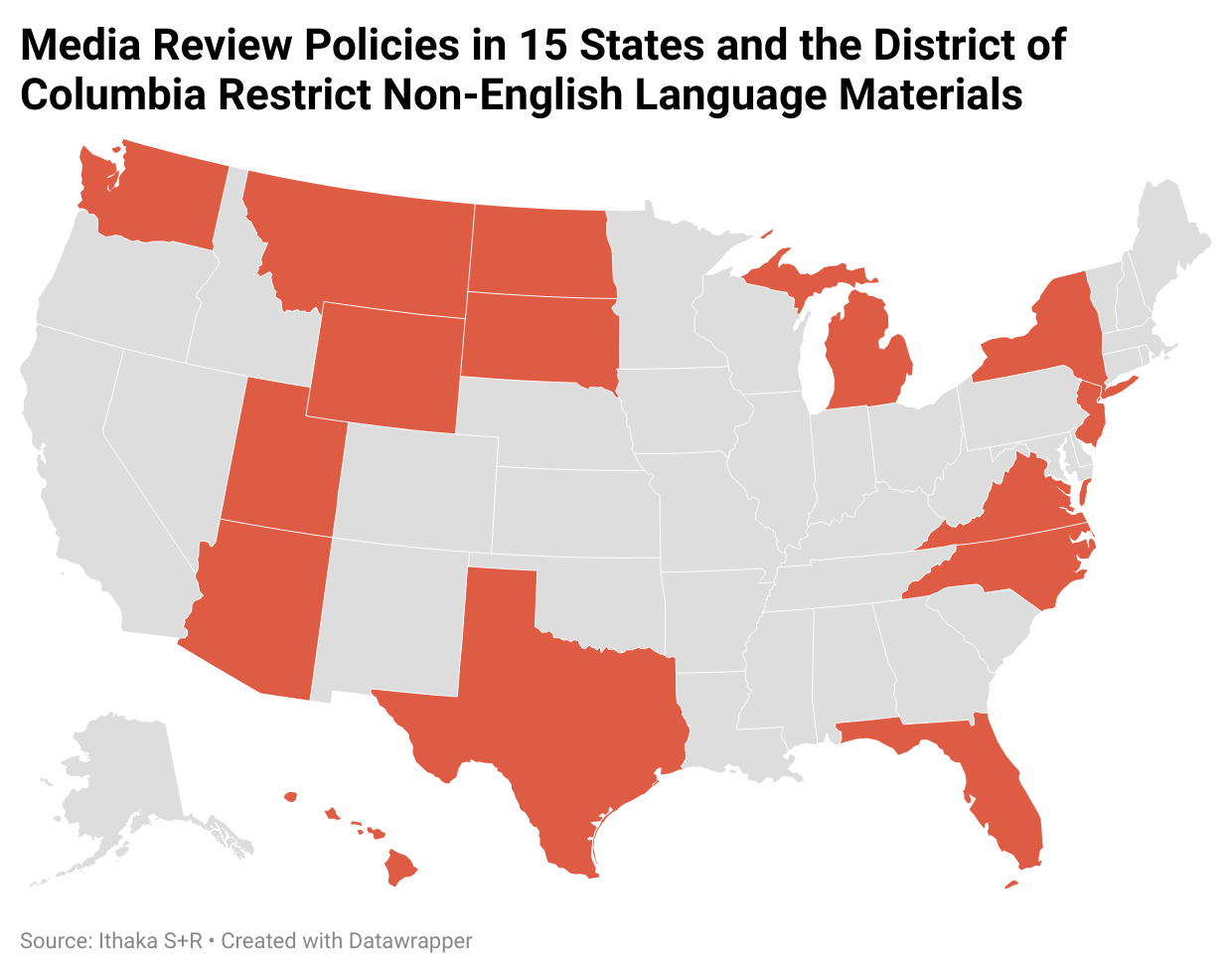

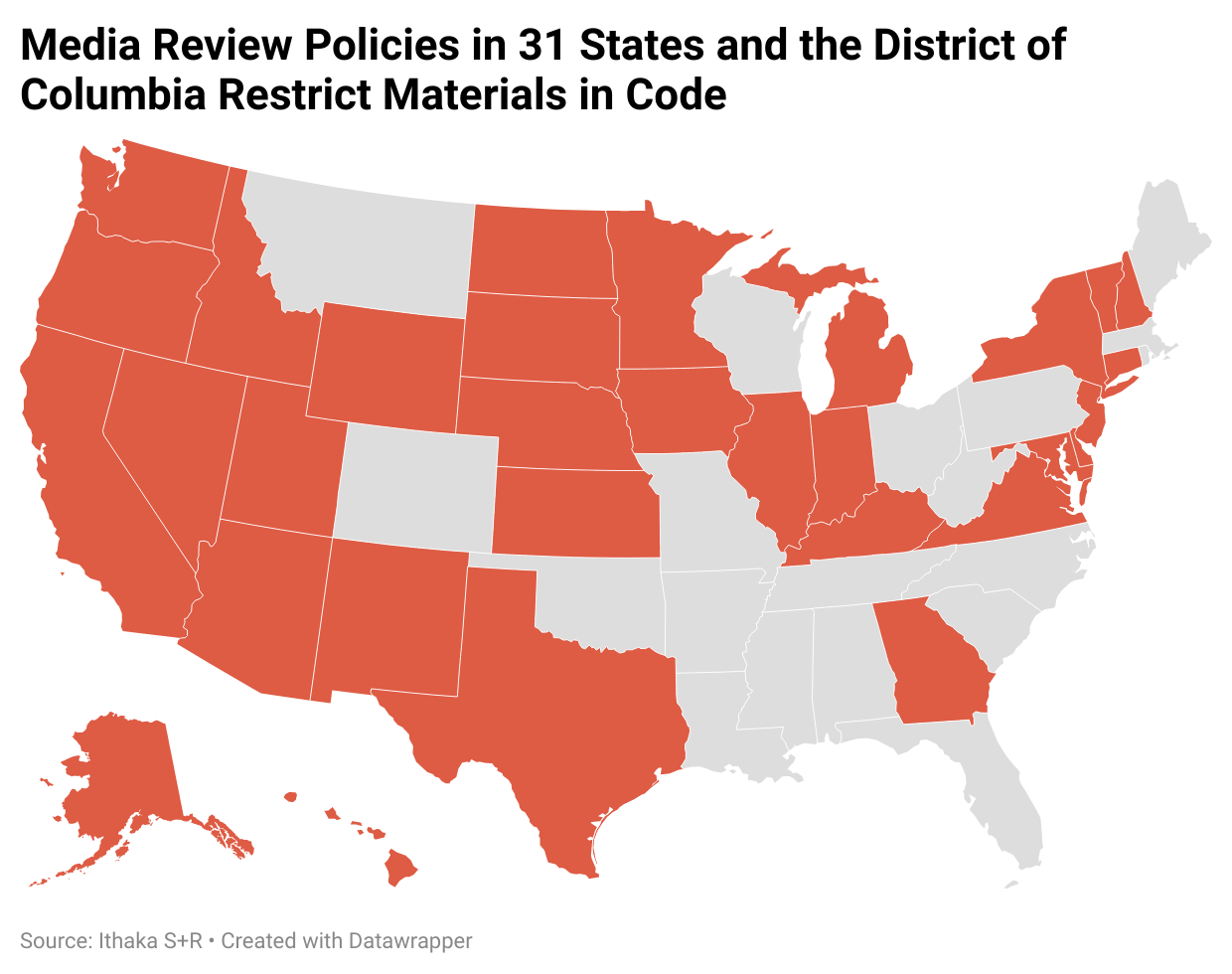

Non-English Language Material and Material in Code

Sixteen states have media review directives that address “non-English language material” (see Figure 3).[38] The majority of these policies lay out provisions for the translation and review of non-English language materials. Presumably, these policies exist in order to protect the rights of students, readers, and correspondents on the inside to communicate in languages other than English, without compromising the security of prisons due to an inability to perform media review. Some DOCs even note that such translation will be done in a timely manner. Utah’s policy, for instance, states that “mail may be delayed for purposes of translation,” but “should not be unreasonably delayed from date of receipt.”[39]

Figure 3

Thirty-two DOC policies prohibit content that is in code (see Figure 4).[40] Twelve DOCs address both content in code and non-English language content in their policies, and in at least two instances, non-English language material policies and content-based prohibitions of material in code are dealt with together. The media review directives of Michigan and, to a lesser extent Virginia, treat non-English language material and material in code as essentially the same, as Michigan’s policy states, “[m]ail written in code, or in a foreign language which cannot be screened by institutional staff to the extent necessary to conduct an effective search.”[41]

Figure 4

The collapsing of non-English language policies and content prohibitions for material in code raises significant questions about implicit and systemic biases and has real world consequences. Many of the non-English language policies that directly address translation procedures provide qualifying clauses—administrative loopholes that allow the DOC to simply reject publications if finding a translator for it proves too “burdensome” or expensive. Procedures from the South Dakota DOC stipulate that “[i]ncoming and outgoing correspondence written in a language other than English […] may be delayed up to an additional ten (10) working days to facilitate translation/verification,” but goes on to note that, “[i]f, after ten (10) days, good faith attempts by staff or other resources to translate the materials are unsuccessful or too costly, or there is reason to believe the content may be in violation of this policy, the material may be rejected.”[42] The staffing and budgetary constraints that many state DOCs are facing suggest that in some cases this may serve as a de facto content-neutral prohibition.[43] These budget and staffing constraints could also move DOC to shift the burden of translation onto the sender or recipient, in this case the person in prison or their friends and family, further shifting the financial burden of incarceration onto those who can least afford it. There is a vast difference in labor between translating a letter and a publication, although in many cases they are governed by the same policies. This emphasizes the difficult situation that DOCs and correctional facilities find themselves in and suggests an opportunity where labor and communication might be streamlined.

Concern over the impact of these policies is not just hypothetical. In June of 2022, NPR reported that the state of Michigan had banned dictionaries in Spanish or Swahili.[44] The spokesperson for the Michigan DOC explained that individuals who “decided to learn a very obscure language” could “then speak freely in front of staff and others about introducing contraband or assaulting staff or assaulting another prisoner.”[45] As the second most prevalent language in the United States, Spanish can hardly be construed as obscure, but it is unclear whether any college programs are directly impacted by this policy. This is a major accessibility concern for students whose first language is not English. It also likely limits educational opportunities for degree programs with language proficiency requirements. It is also not immediately clear how such policies interact with digital media, as companies like Transparent Language have deals with major prison tech providers, in this case Edovo, to provide digital language instruction through tablets within the prison system.[46]

Justifications of Inspection and Censorship

One of the most important facets of the legal history informing these DOC media review directives is the prevalence of general statements that justify inspection of mail and publications and content-based prohibitions. The formulation of these phrases is largely drawn directly from Supreme Court decisions, like Thornburgh v. Abbot, which granted prison administrators broad powers to restrict liberties in the aim of security. These phrases offer broad latitude to prohibit content at the discretion of prison staff and administrators, a fact influenced both by the legal history and the structure of the prison system in the United States—which features major differences across state systems, facilities, and security levels. This generality, while necessary from a systemic standpoint, increases the possibility for the same policies to be interpreted in different ways by different staff. Below, we examine the most common clauses found in media review policies, focusing first on “security, good order, or discipline” clauses, before moving on to analyze various other clauses that draw upon and partially specify “security, good order, or discipline,” (namely: material that might “aid in escape,” “incite violence,” or lead to “group disruption”). While no policy can be sufficiently detailed to cover every circumstance and yet broad enough to be practicable, the broad language found in “security, good order, or discipline” and related clauses provides wide latitude for censorship with few specific examples or scenarios to ground interpretation and protect individual rights.

“Security, Good Order, or Discipline”

Thirty-four states and the District of Columbia have such clauses related to “security, good order, or discipline” in their media review policies (see Figure 5).[47] Examining the way the clause functions in existing policies illustrates just how broadly such phrases function and emphasizes how simply narrowing their scope is not sufficient.

Figure 5

In Arkansas’s policy, the “security, discipline, or good order” clause is the foundation for media review, itself:

Inmates may receive publications only from recognized commercial, religious, or charitable outlets. All publications are subject to inspection and may be rejected when the publication presents a danger to the security, discipline, or good order of the institution or is inconsistent with rehabilitative goals.[48]

The first sentence of the passage limits the purchase of allowable publications to a set of “recognized” vendors (the most prevalent prohibition identified across these directives), while the second sentence deploys a security, good order, or discipline clause to justify media inspection and prohibition. Considered together, the passage also demonstrates how content-neutral and content-based prohibitions function in tandem to allow extremely broad prohibition left almost entirely to the discretion of DOC staff and administrators.

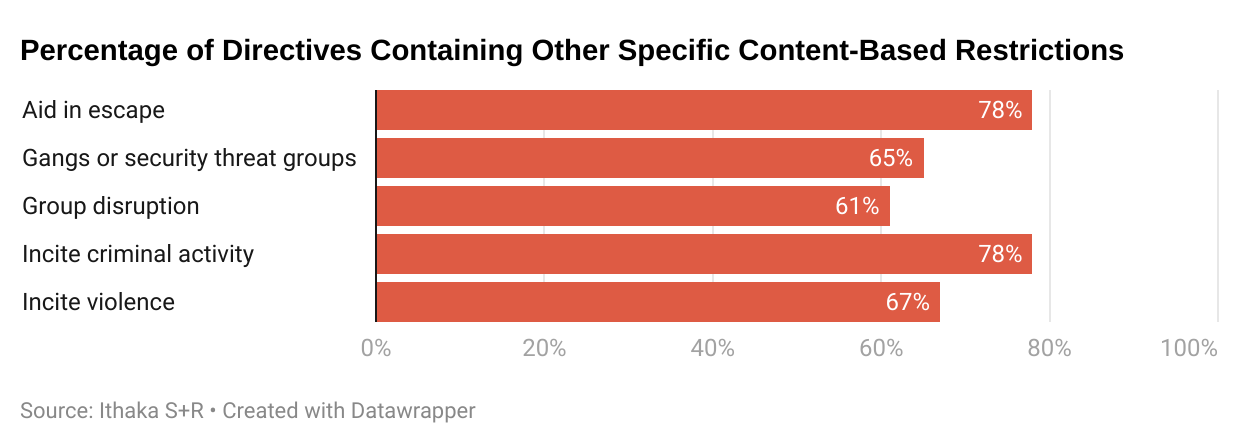

While “security, discipline, or good order” clauses are some of the most important and expansive phrases in media review directives, often remaining almost entirely undefined while serving as the rationale behind and justification for media inspection and prohibition, some policies subdivide security, discipline, or good order concerns into a subset of narrower, yet still very broad, content-based prohibitions. Five additional phrases that further specify types of perceived threats to security, discipline, or good order are also prevalent across policies:

- variations on “aid in escape” or related language arise in 40 directives;[49]

- prohibitions of material related to “gangs or security threat groups” appear in 33 directives;[50]

- clauses banning material that might incite “group disruption” or provoke insurrection appear in 31 directives;[51]

- phrases prohibiting material that might “incite criminal activity” or aid in the breaking of laws can be found in 40 directives;[52]

- and prohibitions against content that might “incite violence” are present in 34 directives.[53]

Figure 6

These thematic specifications, then, serve to denote more specific types of content that might threaten the security, good order, or discipline of the DOC and its facilities. Despite the narrowing in scope that they provide, these phrases can still function very broadly, and narrow interpretations of them can lead to seemingly arbitrary prohibitions. Take for example, “aid in escape” prohibitions. The framing of these prohibitions is sensible in a correctional context. For example, the media review directive from Arizona, which prohibits:

Content that depicts, encourages, or describes methods of escape and/or eluding capture. This includes materials that contain blueprints, drawings, descriptions or photos of Arizona prison facilities or private prison facilities, Public Transportation maps, road maps of Arizona or states contiguous to Arizona.[54]

This passage neatly prohibits publications which provide specific information about facilities, transportation, or maps that might aid in escape. Similar prohibitions also often prohibit blueprints, drawings, or explanations of how locking mechanisms work.[55] In some cases, however, such prohibitions are not connected to the specific context of the state or the facility, as in the policy of Mississippi, which rejects publications that contain “escape plans or maps.”[56] There are, however anecdotal, reports of interpretations of such aid in escape clauses leading to seemingly arbitrary enforcement, like the censorship of books with maps of fantasy kingdoms. In one such example, Kimberly Hricko describes how she was denied access to Game of Thrones while in prison on the grounds that the books contain maps.[57] This raises an important question about access to educational materials: does such a ban mean educational content containing maps is entirely inaccessible? That would effectively ban a number of academic disciplines from being able to operate on the inside. This might preclude, to name just a few examples: satellite imagery and glacial mapping in classes on climate change; national, regional, or combat maps in history classes; and GIS maps and mapping programs in geography.

If such broad definitions are interpreted expansively, it can make policy appear impenetrable and random. And even though DOC set the terms and lay out policy and procedure, few media review directives explicitly include procedural and structural guardrails to assure quality and uniformity, such as policies or procedures laying out specialized training for media review. Moreover, if media review does appear random or unpredictable to people who are incarcerated, it may actually impede rehabilitation by limiting an individual’s sense of choice or empowerment, which research suggests are some of the most harmful psychological effects of institutionalization.[58] Furthermore, such unpredictable enforcement is likely to be perceived by people who are incarcerated as arbitrary or abusive, and it is likely to harm their perception of DOC and facility staff.[59] This could have cascading negative effects on self-censorship, particularly if the appeals process relies on people who are incarcerated to communicate directly with the same officials who appear to be censoring material arbitrarily.

In addition to arbitrary enforcement, there are some documented cases where these thematic specifications have been associated with systematic prohibitions that limit access to entire academic specializations. This is neatly illustrated in the gap between the way “group disruption” clauses are framed in policy and the way they are sometimes documented as functioning in practice.

“Group disruption” clauses serve a broad and variable set of functions across, and sometimes within, media directives. What ties these clauses together are prohibitions against content that may provoke enmity or violence between groups, or cause group-based disruptions in the operation of the facility. In some cases, the clause seems tied specifically to racial or ethnic conflict, as in Colorado’s policy, which prohibits:

Publications that by depiction or description, advocate violence, hatred, abuse or vengeance against any individual or group based upon his/her race, religion, nationality, sex, sexual orientation, disability, age or ethnicity, or that appear more likely than not to provoke or to precipitate a violent confrontation between the recipient and any other person.[60]

In Indiana, on the other hand, “group disruption” is associated with both the incitement of violence and with gang signs; the relevant clause is a prohibition of materials “[d]epicting, describing, or encouraging activities which may lead to the use of physical violence or group disruption (this includes the depiction of gang signs).”[61] In other cases, like the Texas directive, prohibitions focus on the potential for disruption to “achieve the breakdown of prisons” through “riots or strikes.”[62]

It is important to recognize the breadth of these prohibitions because, as authors like Tracey Onyenacho have argued, they may be responsible for de facto bans on books related to Black history.[63] Likewise, PEN America’s “Literature Locked Up” report noted how such content-based prohibitions are sometimes used to block major publications related to civil rights and critical race theory from prisons.[64] While these examples are anecdotal and limited, considered together they suggest that students and readers who are incarcerated may consistently and systematically be denied access to materials that are foundational to academic disciplines or integral to understanding the history of race relations in the United States. This has the potential to produce educational inequities between students who are incarcerated and their free counterparts. Additionally, there is also a need for more research to see if such prohibitions drive representational inequities, as it is possible that authors of marginalized identities may be disproportionately banned from prisons for writing works that reckon with systemic injustice.

Content Protections

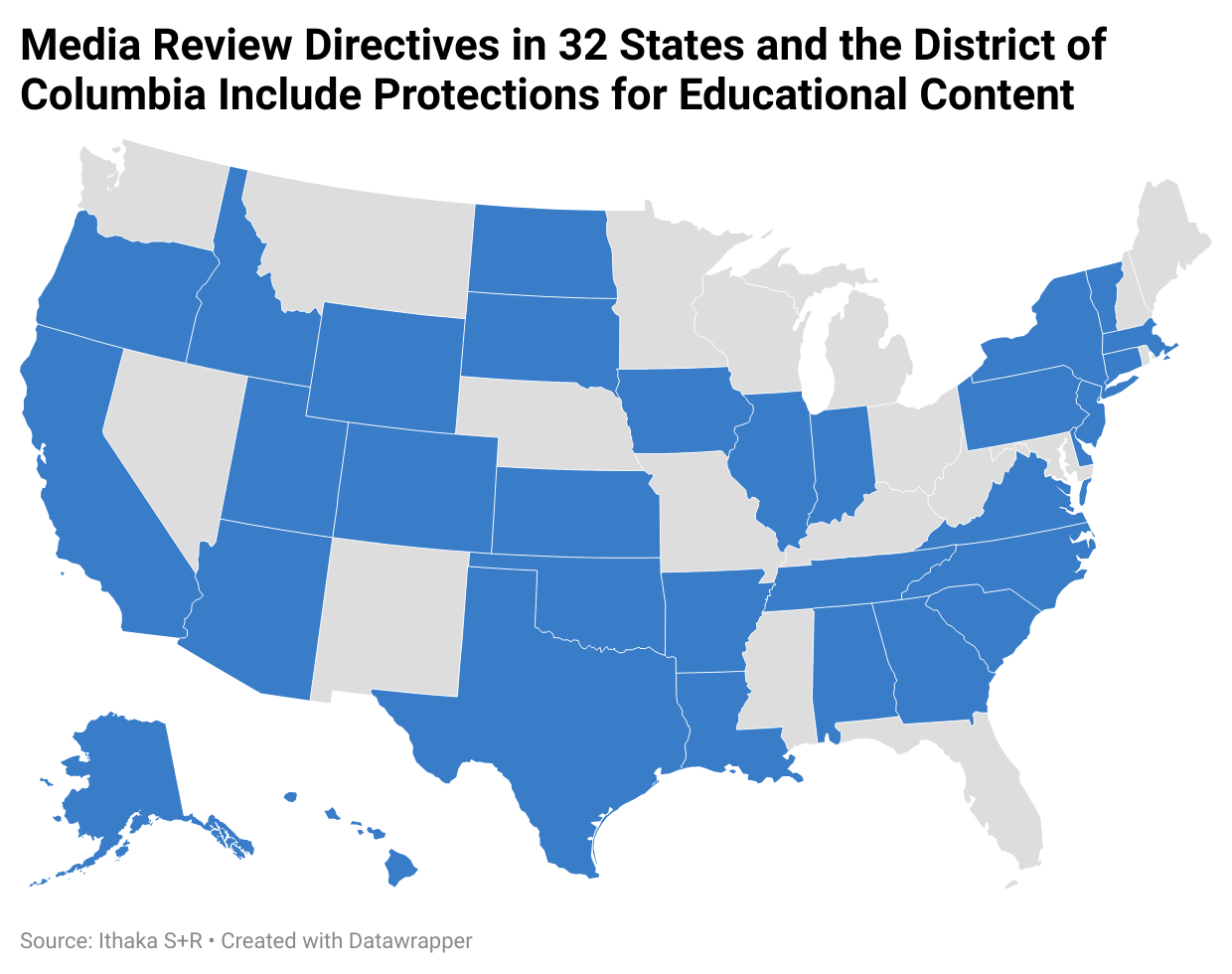

Educational Content Protections

Media review directives frequently acknowledge that there are texts and contexts worthy of exception to censorship. In practice, these content protections are almost exclusively used to ensure access to educational content that might otherwise be prohibited as sexually explicit or obscene material. The media review directives of 33 states include carve outs for content with educational, artistic, or social value (see Figure 7).[65]

Figure 7

The language in South Carolina’s directive is a typical example of how these educational content protections are structured:

This prohibition shall not apply to patently medical, artistic, anthropological, or educational commercial publications, including, but not limited to National Geographic, works of art displayed in public galleries, anatomy texts, or comparable materials.[66]

This passage demonstrates how guardrails to censorship already exist in media directives, even if their primary function is narrowly tied to sexually explicit and obscene content. Additionally, this example is particularly effective because it allows for a broad range of reasons to protect material from censorship: medical, artistic, anthropological, educational. Moreover, it also suggests specific types of materials that would fall under these guidelines. Though content protections for materials of educational or social value, like the one above, already exist in the majority of media review directives, they currently serve a rather limited role. In 30 of 33 media review directives where such content protections exist, they function entirely in relation to sexually explicit or obscene content. Only three states—New York, South Dakota, and Virginia—provide additional content protections; examining the way their content protections function can demonstrate potential ways to strengthen and expand existing educational protections.

New York’s and South Dakota’s directives contain additional provisions to allow for maps that serve educational purposes. South Dakota’s policy states:

[m]aps that do not pose a threat to safety or security are permitted, i.e. education or religious purposes.[67]

While New York’s policy reads:

Maps that are designated for educational purposes and do not violate the above criteria, including the World Atlas, Geographical Map of the United States, etc., are acceptable.[68]

The Virginia DOC offers a much broader content protection, first stating:

This criterion will not be used to exclude publications that describe sexual acts in the context of a story or moral teaching unless the description of such acts is the primary purpose of the publication. No publication generally recognized as having literary value should be excluded under this criterion. Questionable materials must be submitted to the [Publication Review Committee] PRC.[69]

Virginia also uses similar language to protect educational content that might be censored for other reasons. The directive defines what materials depicting violence or criminal activity may be censored and then provides a note carving out educational exceptions:

Material, documents, or photographs that emphasize depictions or promotions of violence, disorder, insurrection, terrorist, or criminal activity in violation of state or federal laws or the violation of the Offender Disciplinary Procedure.

Note: This criterion will not be used to exclude publications that describe such acts in the context of a story or moral teaching unless the description of such acts is the primary purpose of the publication. No publication generally recognized as having literary value should be excluded under this criterion. Questionable materials must be submitted to the PRC.[70]

The protections provided in this clause are not insignificant, as they (theoretically) ensure access to educational materials that might otherwise be banned under a variety of common content-based prohibitions. They also demonstrate that more precise and expansive content protections are possible and have already been written.

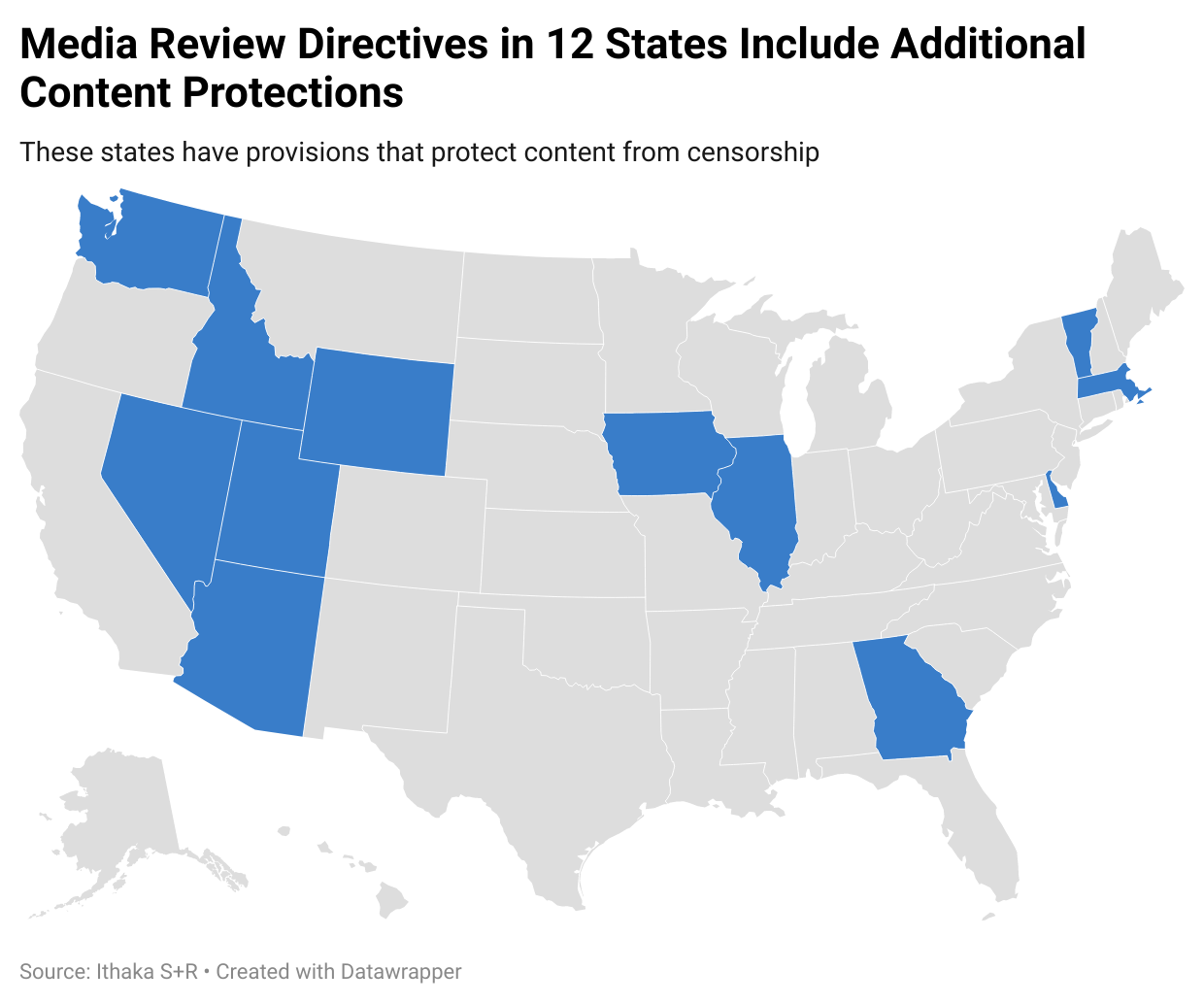

Additional Content Protections

In addition to content protections for materials with educational or social value, two other noteworthy content protections are present in existing DOC policies. The media directives of 12 states have provisions that protect content from censorship by asserting (see Figure 8), to quote Iowa’s policy, that “[n]o publication shall be denied solely on the basis of its appeal to a particular ethnic, racial, religious, or political group.”[71] Washington State’s version of the clause also adds “sexual orientation” to the protected categories.[72] The presence of the word “solely” in every single iteration of this policy is noteworthy, as this clearly ties these exceptions to the broader framework of “security and good order.” Given the undefined nature and broad reach of the content prohibitions examined above, it is not difficult to imagine how this clause might be rendered moot with the citation of “group disruption,” “incite violence,” “gangs or security threat groups,” or “security, discipline, or good order” clauses.

Figure 8

The media directives of Colorado, New York, Pennsylvania, and Utah also contain content protections for material critical of the DOC and prison facilities, with Colorado going so far as to prohibit content from being censored based on “its philosophical, political or social views, or because its content is unpopular, repugnant, or critical of the DOC or other government authority.”[73] While these provisions are a rarity, they can provide a positive model for protecting sources from censorship. New York’s media policy offers the most precise and detailed version of such a clause:

Publications which discuss different political philosophies and those dealing with criticism of Governmental and Departmental authority are acceptable as reading material, provided they do not violate the [nine content-based restrictions defined above]. For example, publications such as Fortune News, The Militant, The Torch/La Antorcha, Workers World, and Revolutionary Worker shall generally be approved unless matter in a specific issue is found to violate the above guidelines.[74]

The clause addresses political philosophy, governance, and criticism of “Governmental and Departmental authority,” moreover, it goes so far as to cite specific publications that might otherwise be considered as violating the content-based prohibition clauses as generally approved. Phrases like “shall generally be approved unless matter in a specific issue is found to violate the above guidelines,” serve a dual function, as well. They simultaneously serve to remind staff that censorship is intended to be the exception, rather than the norm, while allowing enough latitude to censor potentially dangerous issues. The specificity, narrowness, and clarity here reduce the possibility for loopholes that prohibit texts due to stringent and abstract adherence to vague rules and may help promote consistency in enforcement.

Publication Review and Censorship Appeals

Publication Review Procedures and Training

While strengthening and expanding content-based protections can help provide guardrails and guide practice to protect individual rights and access to information, crafting policy so specific as to account for all possible situations is untenable, and DOC staff and administrators will need some flexibility. Given this, publication review procedures and censorship appeals processes can play a crucial role in ensuring that media review policy is enacted fairly and consistently. Media review directives define censorship appeal processes to varying degrees. These policies allow individuals who are incarcerated, and in some cases the publishers they order from, to contest a publication’s censoring. The amount of information available on both publication review committees and censorship appeals processes vary widely between policies: for example, the Illinois directive dedicates roughly 60 percent of the document to these topics; the Arkansas directive, on the other hand, dedicates roughly 25 percent of the document to the issues.[75] Put another way: Illinois dedicates about five and a half pages to laying out these procedures while Arkansas uses only one. This speaks to broader systemic differences about how different DOCs establish, define, and delegate publication review committees and appeals processes, which creates a series of challenges to tracking these procedures across media review directives.

First, the procedures around media review and rejection appeals differ greatly. For example, some DOCs have a centralized process for review and censorship, such as the process laid out by the Kansas DOC, which states:

The Publications Review Officer (PRO) at a correctional facility designated by the Deputy Secretary of Facilities Management, must review all questionable publications received by mail for intended delivery to residents, and must, on an individual basis for each publication, decide whether to allow such publication within KDOC facilities or to censor and deny delivery of such publication based upon the criteria set forth at KAR 44-12-313 and/or 44-12-601. Each facility shall designate personnel to coordinate with the PRO regarding the publication review process.

Any decision to allow or censor a publication shall apply to all adult departmental facilities.[76]

This policy neatly lays out a centralized publication review process, explains whose purview review falls under, and notes that any censorship or acceptance decisions will apply across all facilities. Other DOCs take the opposite approach and leave censorship decisions up to each individual facility. For example, Iowa’s policy simply states that “Each institution shall develop procedures for internal publication review.”[77] The varied patchwork of publication review committees and censorship appeal policies highlights just how different and inconsistent media review is both between and within DOCs. Despite these idiosyncrasies, there are some key features to consider in regard to review committees and appeals procedures.

Sixteen directives make reference to publication review committees in either the publication screening or censorship appeals process.[78] DOC policies containing publication review committees tend to outline their appeals process in great detail and even the briefest among these examples still runs several paragraphs and outlines clear timelines for notification of censorship, windows for individual appeal, and appeal decisions. The remaining 35 media directives, however, vary greatly in how they structure media review appeals.[79] Some reference an appeals process only in passing, without outlining or describing it, such as the New Hampshire directive, which contains an “Appeals” section that simply states:

If a resident or correspondent believes that the NH DOC improperly rejected mail, packages, books or periodicals he or she may appeal to the warden or director in writing within 10 days of the date they were sent notice of the decision.[80]

In other cases, media review appeals follow the standard procedural grievance processes in a given facility or system. The directive from Alaska’s DOC offers a good example of this, and a rare case where it is noted explicitly. It states that “[a] prisoner may file a grievance regarding any action that the Department takes concerning this policy” and reminds readers that to file a grievance, they “must follow the procedures described in DOC P&P 808.03, Prisoner Grievances,” and account for the timeline adjustments in publication censorship appeal.[81] Those of the 35 directives with appeals policies, but not publication committees, are united by the fact that they leave ultimate censorship decisions and appeals processes in the hands of wardens, superintendents, or their designees, rather than those of a specialized committee. This has two obvious drawbacks: first, it limits censorship decisions to one or two individual assessments; second, it has the potential to add lengthy publication reviews to the workloads of administrators who likely already trust the judgment of their staff and who may have no more specialized training or knowledge about how informational and educational access.

Of the 16 media directives that do contain Publication Review Committee policies, only three provide clear information about the members, procedures, or training required of publication review committees. New York suggests that the committee contain representatives, “from Program Services (for example, representatives from Guidance staff, DOCCS Mental Health staff, Facility Chaplains, Education staff, Recreation staff, and Library staff) and representatives from Security staff.”[82] However, New York’s policy does not contain representation mandates and does not suggest how to balance representation between program services staff and security staff.

Pennsylvania and Colorado both go into some detail about the structure and procedure of their committees. The Colorado DOC’s policy provides a very clear definition of the Publication Review Committee makeup:

As established by the administrative head of each facility, this committee should consist of the facility general library technician / librarian, and at least one representative from each of the following areas: Programs, Custody/Control, Intelligence Office, Behavioral Health, and may include other persons deemed appropriate. The administrative head will designate a committee chair.[83]

Similarly, the makeup of the Incoming Publication Review Committee (IPRC) is neatly defined in the Pennsylvania DOC’s media review directive:

The IPRC must include at least three facility personnel selected by the Facility Manager/designee at each facility to review incoming publications and photos that may contain prohibited content. This committee shall contain one member from the Education Department (Librarian, Teacher, or School Principal), one member from the facility Security Office, and the Mailroom Supervisor. Additional staff may be added at the Facility Manager/designee’s discretion. The Mailroom Supervisor shall be designated as the primary contact for the Office of Policy, Grants, and Legislative Affairs.[84]

The actual construction of these committees differ in terms of both membership numbers and departmental representation; however, they both take procedural steps to ensure that publication review occurs in dialogue between educational or library staff and security staff. These two models for publication review committee construction stand out for their clarity and detail, and they also demonstrate some of the potential complications of such construction. First, in the case of Colorado, the addition of the statement “may include other persons deemed appropriate,” has the potential to tip the balance of the committee, which otherwise appears consciously designed to ensure that staff concerned with education, security, and rehabilitation are all fairly equally represented. In the case of Pennsylvania, only one representative is drawn from education and there may not necessarily be a trained librarian on the committee.

While Colorado and Pennsylvania provide a good deal of information about public review committee formation and representation, they do not provide information about training procedures related to media review. In fact, among the wide variety of provisions defining these committees and citing their role in the publication review and appeals process, there are virtually no explicit provisions describing the overarching goals or training of such committees. The rare exceptions are extremely limited clauses, such as the Oklahoma DOC’s note that “Training will be provided upon request by the office of the General Counsel in the review, recognition and disposal of non-acceptable materials.”[85] Considered together, representation and training procedures are an area of great opportunity for expanded policy to help ensure fair and equitable media review, a topic we expand upon in the recommendations section.

Review Conditions and the Appeals Process

The role and activity of public review committees also varies across directives. In some cases, they are relegated to reviewing only censorship decisions which have been appealed, in others, they make all substantive decisions regarding what publications may or may not enter the facility. While recognizing that the burden of assessing each publication on an individual basis would be time consuming and could potentially pull staff that are already overburdened from their other duties; these committees have a special role in protecting the rights of people who are incarcerated and, if given proper membership and training, should be specially equipped to implement media review policy in a way that respects security and the right to read and learn.

Appeals processes are one of the most important and most widely varying policies provided for in media review directives: the process by which an appeal is made, who might make an appeal, how long they have to make it, and how long they might need to wait for a determination all vary by DOC, and in some cases by facility. Vermont’s policy on publication review and appeals presents a model for a decentralized, facility-determined process:

The DOC shall establish a review and appeals process for the disapproval of publications. This process shall require the DOC to notify the inmate and publisher whenever a publication is disapproved.

- These notifications shall include an explanation of why the publication was disapproved.

- The notification to the publisher shall inform the publisher that they may appeal the decision to the Superintendent or designee.[86]

Despite its brevity, this example demonstrates some of the key features frequently found in DOC media review appeals processes: formal notification procedures for the person who was set to receive the publication and the publisher who sent it, and some provision allowing an appeal of that censorship decision. The fact that there are no prescribed timelines or procedures set forth in this policy is representative of both the variation in timelines (when stated) across policies and the fact that different facilities may have different constraints in terms of appeals turnaround. For example, Oklahoma requires that prospective recipients of publications be notified that their material is being censored within 72 hours of the decision and the publication review appeals process follows the normal grievance process.[87] Timelines for how long one has to submit a grievance are not immediately clear, even if one examines the separate section of the Oklahoma DOC’s operating procedures outlining the grievance process.[88] Moreover, an examination of the grievance process in detail demonstrates that the first step is an informal appeal, requiring direct and informal communication with the decision maker; it is only after this informal appeal has been exhausted, can the formal grievance process be initiated.[89] While the appeals and grievance process is meant to guard against arbitrary enforcement and overreach, forthcoming research from Ithaka S+R into self-censorship suggests that placing the onus of appealing onto those who are incarcerated or third party programs that serve them acts as a strong deterrent to using these formal channels. Fear of reprisal, or the deterioration of relations with the DOC, may mean that these processes are never used, even when petitioners have a strong case.

The policy of the Kansas DOC stands in stark contrast to those that require informal appeals. It has the distinction of being the only automatically initiated appeals process. The media review directive states: “All publications censored by [publication review staff] are to be automatically appealed and reviewed by the Secretary’s designee.”[90] While the automatic initiation of appeals likely reduces interpersonal concerns and may reduce instances of self-censorship, the single layer of appeals here and the fact that appeal rests on decisions from two individuals, the publication review officer and the secretary’s designee, appear limiting. Minnesota, for example, has a special appeals process for publications, rather than simply relying on the standard grievance process, and it has a two-layered appeals policy, allowing appeal first to the mailroom supervisor and then to “the facility correspondence review authority.”[91] The New York DOC also provides a unique appeals process with facility media review committees making initial determinations that are appealable to the system-wide central office media review committee.[92]

There is no DOC whose policy integrates a publication review committee, an automatic appeals process, and a dual-level appeal. Such a policy could take decision-making out of individual hands, limit self-censorship and concerns of reprisal, and provide checks to ensure that policy enforcement is consistent and fair. Given the broad variations across, and potentially within, DOC appeals processes, this appears to be one area where structural intervention and coordinated conversation might have an outsized impact on censorship.

Recommendations

The history, language, and structure of contemporary media review directives arise out of the tension between balancing the protection of the individual rights of people who are incarcerated and the safety and security of the facility, staff, and people who are incarcerated. As this report demonstrates, however, the language of media review policies has tipped this balance in the direction of censorship, and currently provides insufficient protection for people’s right to read and learn. Rather than attempting to push policy between these two poles, we contend that the issue should be reframed and seen not as a conflict between individual rights and institutional or social security. Instead, we should consider how policy revisions that increase access to education and information can create a safer environment inside prisons, streamline workflows, and improve communication.

Based on our review of existing policies, we designed a model media review policy, provided in Appendix 1, to help strengthen content protections for educational, informative, and other recreational materials. We recommend a series of changes to media review directives and related policy designed to: (1) narrow the role of “security, good order, and discipline” clauses and establish guardrails to limit overreach; (2) strengthen content protections to ensure access to non-threatening and educational material; (3) clarify the form, function, and procedures of publication review committees; and (4) institute an automatic censorship appeals process to reduce self-censorship and retaliation concerns. These recommendations are made after an exhaustive review of existing media review directives.

Narrow the Role of “Security, Good Order, or Discipline” Clauses

“Security, good order, or discipline” clauses function as overly broad censorship justifications and can be interpreted and deployed in ways that needlessly limit access to information and publications. Requiring more specificity in censorship justifications will help to reduce overzealous censorship and increase transparency, without creating undue burden. We understand the legal importance of the phrasing and its place in the history of media review; however, we recommend the following measures to increase specificity and establish more policy guardrails.

- Shift from broad, generalized justifications to more specific ones.

- Move from rote justifications that cite only policy and instead cite relevant passages or pages of the material.

- Specify how the publication in question violates policy and why that matters.

Strengthen Content Protections

Content protections already exist in many policies, but their application is primarily limited to protecting content that might otherwise be censored as sexually explicit or obscene. These policies may be greatly expanded to protect access to media, especially publications with educational, artistic, or informational value. Additionally, content protections that ensure access to materials that appeal to a particular ethnic, racial, religious, or political group, while not as common, can serve an important role in ensuring equity in representation and accessibility. We recommend:

- Strengthening content protections for media with educational, artistic, or social value and expanding such clauses to protect material that might otherwise fall under other content-based restrictions.

- Strengthening and expanding content protections for media perceived as appealing to a specific group of people.

Offer Model Examples of Policy Enforcement

To further provide clarity on how policy should be enforced, add specific examples demonstrating each of the following:

- Appropriate censorship that cites a real publication, category for its prohibition, and explanation of what content in it is banned, and for what reason(s);

- Censorship that is inappropriate for overreaching or for potentially discriminating against a particular racial, ethnic, or religious group;

- Censorship that may be appropriate but is inadequately justified or explained.

Restructure Publication Review Committee Membership and Procedures

Adjusting the systems and structures through which censorship functions will have a greater impact than policy language and framing changes. Given this, publication review and appeals processes have an unparalleled role in censorship decisions. Therefore, we recommend the following:

- Ensure that publication review committees have representation from librarians, DOC education staff, individuals who are currently incarcerated, and, when appropriate, postsecondary educators or administrators;

- Provide trainings on the history of media review, unconscious bias, and first amendment rights to all staff and committee members who engage with media review;

- Outline PRC meeting procedures in detail and ensure that the committee meets on a regularly scheduled basis and upon special request.

Enact Automatic Censorship Appeal

Although processes for censorship appeal vary greatly, very few policies provide for an automatic appeals process that incorporates a publication review committee. Such a structure would take the burden of appeal out of the hands of individuals who are incarcerated and ameliorate logistical and ethical challenges. We recommend:

- Enact an automatic censorship appeals process;

- Ensure that such a process consists of at least two phases, and at least one of those phases involves a representative publication review committee.

Special Thanks

This report is one facet of a larger project made possible with funding from Ascendium Education Philanthropy, and we would like to extend our gratitude to them for making this and two forthcoming reports possible. We also owe thanks to all those who provided feedback and advice during the drafting process. Special thanks to the Coalition for Carceral Access in Literature and Learning and to Jeanie Austin, jail and reentry services librarian at the San Francisco Public Library, and James Tager, research director at PEN America, for their feedback on the Model Policy. From Ithaka S+R, we thank Catharine Bond Hill and Roger C. Schonfeld for their feedback and support, and Kimberly Lutz and Juni Ahari for their editorial and communication support.

Appendix: Model Media Review Policy

This appendix features a model media review policy that incorporates the recommendations outlined above and builds on existing policies and procedures. The model policy provided here collates and cites features from existing media review directives, synthesizing some of the most precise policies that promote security while maintaining student or reader rights. In providing this synthetic sample policy, we aim to concisely demonstrate how existing policy already exemplifies our recommendations, and to provide model policy in a brief, coherent design that can easily be cited or sampled.

The model policy features nine distinct sections focusing on different aspects of the media review process. The policy will appear familiar in both structure and content to readers who have examined media review directives, with the exception of the significantly expanded first and last sections, Policy Purpose and Goals and Training Materials, respectively. Linguistically, we have chosen language that operates at the facility level for two reasons: (1) for the sake of streamlining language and (2) as a means to ensure balanced representation in Publication Review Committees across all facilities. This structure is not intended as a value judgment, and we do not wish to imply that facility-level review policy is more or less valid or valuable than system-level policy. Moreover, we recognize that Department of Corrections media review structures vary by system and that some states will be required to establish publication review committees at a system-wide level, rather than at the level of facility.

We provide this model policy as researchers familiar with the broad landscape of media review policy who are invested in making trends across that landscape legible.

1. Policy Purpose and Goals

1.1. It is Department policy to encourage and facilitate access to publications to promote recreational reading, personal enrichment, and education, both formal and informal, among those in the Department’s custody. As a growing body of evidence makes clear, access to such resources promotes security and good order, fosters an atmosphere of mutual respect, and promotes conditions conducive to personal growth.[93] The Department’s goals in exercising media review are therefore:

1.1.1. To provide persons in custody the opportunity to explore ideas, information, and concepts originating outside the institution;

1.1.2. To maintain family and community ties;

1.1.3. To facilitate communication with courts and legal counsel;[94]

1.1.4. To support recreational reading, personal enrichment, and lifelong learning;

1.1.5. To support formal educational programming by facilitating access to academic resources;

1.1.6. To maintain a safe environment for both persons in custody and staff.

1.2. Accordingly, persons in custody shall be allowed to subscribe to and possess a wide range of printed material such as books, magazines, and newspapers, subject to the provisions of this directive.[95]

1.3. Likewise, programs serving the Department’s facilities shall be allowed to provide access to reading and educational materials, subject to the provisions of this directive.

2. Terms and Definitions

2.1. Security, Good Order, Discipline, or Rehabilitation

2.1.1. The Department recognizes that its legal power to censor material and restrict the rights of residents comes specifically from circumstances that threaten security, good order, discipline, or rehabilitation. In the aim of transparency and consistency, The Department understands threats to security, good order, discipline, or rehabilitation in the following terms:

2.1.1.1. Threats to security: tangible, imminent threats to the security of the facility may endanger the rehabilitation of residents or the health, privacy, or safety of staff or residents, must be corroborated by evidence and not based on speculation.

2.1.1.2. Threats to good order: tangible, imminent threats to the operation of essential programming in the facility, must be corroborated by evidence and not based on speculation.[96]

2.1.1.3. Threats to discipline: tangible, imminent threats to the working operation of the facility, such as escape attempts, organized smuggling of contraband, violence, or riots; must be corroborated by evidence and not based on speculation.

2.1.1.4. Threats to rehabilitation: tangible, imminent threats to the rehabilitation of residents, including large-scale or systematic disruptions of counseling or therapeutic services, must be corroborated by evidence and not based on speculation.

2.1.2. Examples of justified and unjustified censorship under these definitions might include the following:

2.1.2.1. Unjustified censorship might include: Rejecting a publication because it addresses the history of systemic racism in the United States and has a chapter focusing on incarceration.

2.1.2.1.1. While a sensitive topic, the above subject matter will not necessarily lead to violence or disruption.

2.1.2.2. Justified censorship might include: Rejecting a publication that provides detailed instructions on how to disrupt security systems or how to wage guerrilla warfare in confined spaces.

3. Publication Review Committee (PRC) Guidelines and Procedures

3.1. PRC Members and Training

3.1.1. Each facility shall establish a Publication Review Committee consisting of:

3.1.1.1. a trained librarian, and at least one representative from each of the following areas: Programs, Custody/Security, Counseling and Mental or Behavioral Health. If applicable, the committee will also include a representative faculty member or administrator from affiliated higher education in prison programs. The administrative head will designate a committee chair.[97]

3.1.2. All persons who perform media review, including the Publication Review Committee members, will participate in yearly First Amendment rights, censorship guidelines, and unconscious or implicit bias seminars.

3.2. Publication Review Procedures

3.2.1. Initial Review

3.2.1.1. Incoming publications will be screened in accordance with the Department’s goals outlined in Section 1 of this directive. Publications shall generally be approved unless matter in the specific publication falls into one of the guidelines outlined in section 7.3, “Censorship Guidelines.”

3.2.2. Automatic Appeals[98]

3.2.2.1. When a staff member reviews and denies a publication that does not appear on the Department’s Reviewed Publication List, they must:

3.2.2.1.1. (1) complete the [relevant form] by entering the following:

3.2.2.1.1.1. (a) publication name, if known, or a brief description of the publication; (b) date of the publication; (c) publisher’s name and complete mailing address; (d) reason(s) that the publication was denied with brief narrative why the contents violates the policy, including page numbers; and (e) within two business days, notify the resident that the automatic appeals process has been triggered by placing a completed copy of [relevant form] in the institutional mail system at the same time that they initiate the automatic appeals process and notify the PRC. If the PRC determines that the publication must be censored or rejected, they will notify the resident with [relevant form] and provide notice to the publisher using [relevant form].

3.2.2.2. Publication review officers must make available to the PRC the [relevant form] justifying the censorship decision and the material to be censored.