The Strategic Alignment of State Appropriations, Tuition, and Financial Aid Policies

In response to the Great Recession in 2008 and 2009, states reduced their expenditures on many public services and goods, including substantial cuts to higher education spending. Despite a strong economic recovery since the Great Recession and significant increases in student enrollment, most states’ spending on higher education has not returned to pre-recession levels. Reductions in state spending and rising costs have led a number of public colleges and universities to increase tuition, making college less affordable for many students and their families.

Reductions in state spending have real consequences for the postsecondary opportunities available to lower-income students, and increases in state spending have a demonstrated positive impact on students’ likelihood of enrolling in and graduating from college. Yet, there is limited understanding and little consensus about the level of state spending that is necessary to achieve desired outcomes and the extent to which those levels vary across states, regions, and institutions. The period before the Great Recession is often used as an anchor to measure whether state spending has “recovered,” but prior to the Great Recession, there were still substantial disparities for lower-income and underrepresented minority students in terms of college enrollment and completion rates. There is little reason to think that returning to pre-recession levels would be a panacea for the inequities that remain today.

In this issue brief, we argue that increased state spending on higher education is a necessary but insufficient condition to maximize postsecondary opportunity and eliminate persistent equity gaps. Instead, each state should examine all the financial levers at its disposal and devise an approach to higher education funding that optimizes these levers to achieve state-specific access, success, and equity goals. This policy brief focuses on the three most prominent financial levers: appropriations, financial aid, and tuition-setting. Each lever represents one mechanism by which state governments fund postsecondary education. However, when these levers are not strategically aligned, inefficiencies may arise. For example, conflicting incentives, duplicative efforts, and unclear goals may reduce efficiencies in state higher education expenditures, with real, negative consequences for students, institutions, and taxpayers.

To make the case for strategic alignment, we examine the potential inefficiencies that misalignment may yield and discuss the social and economic benefits of aligning funding and finance policies. We examine the effects of changes in policies related to appropriations, state financial aid programs, and tuition-setting. We then look at how the alignment of higher education finance policy can improve access and attainment for historically underserved students.

We gratefully acknowledge the Joyce Foundation for supporting this issue brief.

Making the case for strategic alignment

States often use higher education spending as the balancing wheel for state budgets.[1] As the 2008 Great Recession set in, states had less tax revenue to spend, and higher education budgets took a steep hit. While spending has recovered somewhat in recent years, there is still the expectation that public colleges must do more with less. Although research shows that increased spending on public higher education improves access and attainment rates, we suggest that a targeted approach to these increases is necessary given state budgetary constraints. By strategically aligning appropriations, tuition-setting policies, and state financial aid programs, policymakers can maximize the benefits of public spending on colleges and universities.

The efficient funding of higher education is important for maximizing the benefits of the state expenditures that public colleges receive. Constrained budgets and an increased emphasis on results for students means every dollar has to count. Although the costs of providing postsecondary education have steadily increased, the level of state support has not grown accordingly. As such, improving efficiency in state spending can help government maximize opportunities for students as well as the individual, social, and economic benefits of higher education.

When states align various higher education finance policies they can improve efficiencies through a number of mechanisms such as (a) avoiding offsetting incentives for institutions, (b) avoiding duplication of effort, (c) avoiding unintended incentives or consequences for students, (d) avoiding confusion about what the state’s higher education goals are, and (e) directing funding where it is most valuable. These effects of financial alignment are important as state funding per student decreases and public dollars become a shrinking share of colleges’ total revenue. As state governments face increased competition for expenditures (e.g., rising health care costs and pension obligations), they must consider strategically aligning higher education policies to maximize the effectiveness of each dollar spent.

In addition to improving efficiencies, state governments should see the strategic alignment of financing as an economic opportunity. By aligning the three financial levers described in this brief, states can improve access and attainment for historically underserved students. The increased opportunities for these students – who otherwise may contribute less to the economy, require more social services as adults, and generate less tax revenue for the state – are a wise investment for policymakers seeking to improve the financial health and outlook of their state. Moreover, by considering the various effects of educational investments across different programs and populations, states can help tailor their strategies to improve access and attainment and, in turn, reap large social and economic benefits.

Below we discuss what is known about the effects of each of the three primary financial levers: state appropriations, tuition setting policies, and financial aid programs. In order for states to effectively align these policies with overarching goals, it is important to understand the discrete effects of changes to each. We then turn to a discussion on the alignment of such levers, providing examples of states that have successfully improved efficiency as well as economic and social outcomes.

The importance of state appropriations

State appropriations are the dollars given directly from the state government to public colleges in order to fund operations. These dollars are intertwined with public financial aid programs and tuition setting policies, but represent a unique portion of a public college’s revenue.

Appropriations play an important role in access, affordability, and quality. The effects on affordability are the most immediate and obvious. One study estimates that a dollar decline in state appropriations is associated with a 26 cent increase in tuition at state institutions.[2] The effects of declines in state appropriations on access and quality,[3] while lagging, can be severe. Higher tuition puts public college out of reach for some state residents, particularly those who would benefit most from the social mobility higher education can provide. A higher price tag also makes it less likely that students complete college, as costs mount over time and the risk of a financial shock disrupting their education rises. When changes in appropriations lead to reductions in institutional expenditures on education and services, the effects on students’ graduation outcomes may be larger still and thus both sides of the coin need to be considered. [4]

The long-term effects of increased state appropriations have been demonstrated at two- and four-year public institutions.[5] By their mid-30s, students who benefited from an increase in state appropriations had lower levels of student loan debt, higher credit scores, and an increased likelihood of owning a car or a home. Both the short-term completion increases and the long-term economic outcomes that result from increases in appropriations reflect an ongoing concern that state divestment over recent decades has reduced the quality of public education.[6] While access and affordability are important, we must ensure students have access to quality educational opportunities, a characteristic directly impacted by funding.

How states determine appropriations

The approaches that states use to appropriate higher education funds differ, but generally fall into one of three models: incremental funding, formula funding, and outcomes-based funding.[7]

- Incremental funding (or base-plus funding) is the simplest allocation method. It uses previous years’ funding and increases by a certain percentage per institution. This does not take into account the number of students enrolled – if, over time, the annual percentage increase lags behind the increase in students enrolled, then per-student funding will naturally decline.

- Formula funding allocates funds based on the number of students enrolled, and in some cases, the type of institution. In some states, research institutions and institutions with graduate programs receive more per-student funding than community colleges or four-year institutions that only offer undergraduate degrees and conduct less research.

- Outcomes-based funding (OBF, or performance-based funding) allocates funds based, in part, on outcomes instead of inputs. Instead of awarding funding based on the number of students enrolled, states that use OBF allocate funds based on factors like course completion, degree progression and efficiency, degree completion, workforce readiness, research and public service, and affordability, among others. The share of an institution’s total funds that are allocated based on its performance ranges from less than five percent to, in a few states, more than 25 percent. As of 2018, 30 states are currently using or developing some version of outcomes-based funding in at least one state college system.[8]

Historically, incremental funding has been used to fund public higher education. It was only after World War II, and the influx of GI Bill recipients, that states began shifting funding strategies to be formula-based using enrollment as a primary determinant of funding. Formula funding was intended to improve upon incremental funding by being more responsive to fluctuations in the number of students each school serves. Some critique these approaches to funding as overly simplistic and lacking the necessary nuance to adequately respond to the unique funding needs of each institution.[9]

State policymakers are increasingly adopting outcomes-based funding (OBF) policies as a way to respond to public pressure that college costs have continued to rise, while attainment remains flat and student debt increases. Yet, there is little conclusive evidence that OBF improves student outcomes; rather, some evidence suggests that OBF policies may have serious unintended consequences. As a shortcut to improve student outcomes, colleges and universities may reduce the academic rigor of programs, enroll fewer students – like lower-income and underrepresented students – who are less likely to graduate, and encourage students to pursue credentials instead of associate or bachelor’s degrees.[10] To address these unintended consequences, some OBF policies account for lower-income student enrollment in the formula to determine how state funds are distributed. A few states also account for how colleges serve underrepresented minorities, adult students, and veterans in their formulas.[11]

Although OBF policies have become more common in recent years, many states only allocate part of their appropriations via OBF metrics, and a combination of these three approaches is used to determine overall state funding. The variation in combinations is important to understand, as each model has been shown to have differing effects,[12] and these effects vary across institutional characteristics.[13]

California exemplifies a move towards a funding formula that considers equity alongside outcomes. While some states have included equity premiums within their OBF metrics, California has included equity in its formula funding. In the 2018-19 budget, each California community college received funding through a combination of enrollment counts, the number of low-income students it serves (under the assumption these student require additional resources), and student outcome measures.[14] The model eventually will be weighted between the three factors at 60, 20, and 20 percent, respectively. Additionally, state appropriations under the new Student Centered Funding Formula are awarded after local tax revenues, student fees (including grant aid used to cover these fees), and other revenues (e.g., timber tax revenue).[15] By explicitly addressing equity in its funding model, accounting for revenue colleges may receive from state higher education grants as well as other tax revenue, and centrally setting tuition prices, California has aligned its postsecondary financing in a way that may limit inefficiencies and avoid conflicting goals.

Appropriations play an important role in public colleges’ operations, and fluctuations in state funding can result in uncertainty for institutional leaders. Policymakers and governing bodies should consider the impact of these uncertainties on the year-to-year operations of a college. For example, if a college is unable to depend upon the state for resources, it is likely to seek other forms of revenue – from increased tuition dollars, auxiliary services, patent revenue, or other sources – which has the potential to compromise institutional missions and undercut access and student support.[16] As seen in the recent proposed cuts to the Alaska higher education system, state institutions with erratic funding or dramatic cuts to appropriations run the risk of losing accreditation on the grounds that the institution cannot function without proper financial support.[17] Volatility in state support limits the ability of colleges to plan for the future, provide a quality education, and may jeopardize students’ labor market outcomes if colleges become unaccredited.

In addition to avoiding volatility, equity in state appropriations is necessary to improve access and attainment for historically underserved populations. The funding model adopted for the California Community College System is intended to ensure schools serving the most disadvantaged students receive appropriate resources to serve those students. The use of state appropriations to improve the instruction and student supports at public colleges is the most effective way to increase student attainment. An increase in funding is necessary to provide a quality education, but must be considered vis-à-vis student aid programs and tuition-setting policies. Providing adequate resources through other financial levers to lower the cost and barriers to entry is necessary to improve access for lower income students. Together, these policy levers can align to provide more postsecondary opportunities for historically underserved students.

The effects of tuition-setting policies

Tuition-setting policies often strive to promote access and affordability, but tuition is only one facet of affordability. Here, we describe different tuition-setting practices, the importance of net price on access and affordability, and how tuition setting should be considered in relation to appropriations and state financial aid programs.

According to a 2017 SHEEO survey, some states, including Washington, allow institutions flexibility in setting tuition, but for the plurality of state public college systems, tuition policies are set by their governing boards.[18] The same survey indicated that 20 states, including Maine, Montana, and Oklahoma, have recently proposed or enacted tuition freezes. While tuition is the sticker price students see when applying to college, the actual price students pay reflects discounts from federal, state, and institutional aid. The published tuition does not, therefore, accurately reflect the net price a student may pay. Private institutions have long used this “high-tuition/high-aid” model where a relatively low percentage of students pay the sticker price and most others receive discounts. This model is now becoming more common among public institutions.

High sticker prices may depress application rates from more price sensitive students.[19] Historically underserved students have shown a greater aversion to higher tuition prices, and thus sticker shock may decrease their enrollment.[20] These effects may be particularly pronounced at community colleges, which enroll more historically underserved students and provide postsecondary opportunities to those on the fringes of higher education.[21]

While an important top-line number for all students, the tuition rate is especially significant for DACA students who are not eligible for federal financial aid and thus depend on lower tuition to make their education affordable.[22] Higher tuition prices have been shown to decrease the enrollment rate of undocumented students at public colleges.[23] In these ways, tuition setting plays an important role in access, but its role is confounded with other higher education policies, like state student aid programs, to generate the net price.

When states lift regulations on tuition setting at public institutions, there is the potential for high-tuition/high-aid models to develop. These policies appear to be regionally concentrated in the Northeast and Midwest,[24] and they are related to party control in state government as well as the robustness of the private postsecondary market.[25] Some have argued that high-tuition/high-aid models enable states to direct funds directly to lower-income students rather than spending money to keep tuition prices low for high-income students.[26] However, the high-tuition/high-aid approach has the potential to exacerbate inequity by giving colleges the autonomy to use institutional aid to lure wealthy, high achieving students in an effort to increase rankings or prestige. In fact, these policies at public colleges in some states are linked to lower-income students paying higher net tuition than at public colleges in states that have kept tuition low.[27] It appears that public colleges that switch to the high-tuition/high-aid model may not be redirecting funds that were previously used to keep published tuition low towards lower-income students, as proponents of the high-tuition/high-aid suggest will happen.

Although state governments or higher education governing bodies may play an outsized role in tuition setting, the vast majority of states allow institutional autonomy for tuition revenue spending. That is, each institution is able to use its tuition revenue to meet its institutional goals. There can be some restrictions; for example, public colleges in some states must set aside a certain portion of tuition revenue for financial aid.[28] Washington State requires institutions that increase tuition above a state-mandated threshold to set aside five percent of all tuition revenue for need-based aid.[29] Similarly, in Texas, as part of the deregulation of tuition-setting policies, the state mandates that public schools set aside at least 15 percent of tuition for need-based aid.[30] Meanwhile, Iowa eliminated its set-aside mandate in 2012; however, public colleges are still able to use tuition revenue to fund need-based aid. Institutional aid, which lowers the net price, contributes to the opacity of college costs and thus potentially amplifies the deleterious effects of sticker shock described above.

The implications of tuition-setting authority on institutional behavior should be considered by policymakers. Tuition-setting policies are an opportunity to guide public colleges towards state educational goals. The ideal level of influence government should have on tuition setting may be impacted by the state’s higher education market, economic and educational needs, and political and social climate. Nevertheless, policymakers should consider ways to use this lever, in accordance with appropriations and state financial aid, to efficiently and effectively align policies to improve public higher education.

The importance and variation of net price

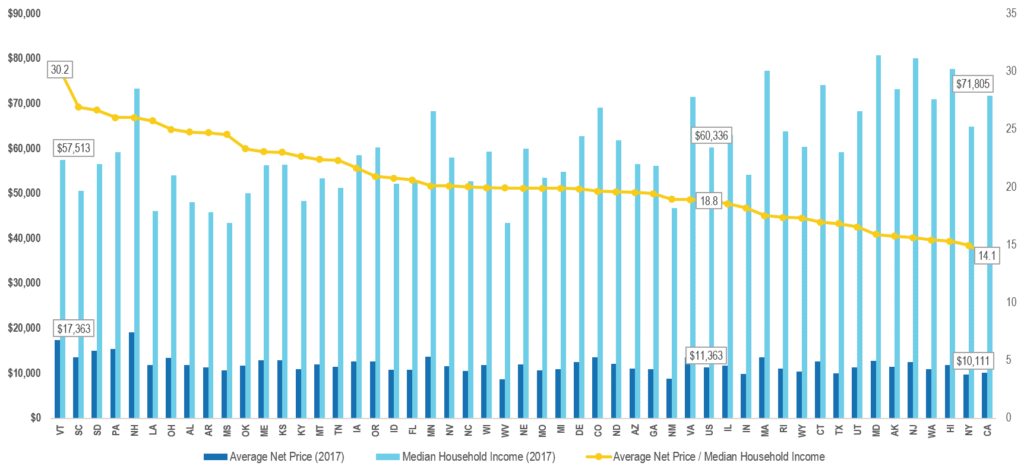

Although sticker price is important, net price more accurately reflects what a student pays. Just as it is important to consider total tuition in relation to the discounts given to students, we believe it is imperative to consider the net price in relation to students’ ability to pay. For instance, comparing the net price of a college in Mississippi and Massachusetts may not fully capture affordability, as incomes in Mississippi are generally much lower than in Massachusetts. Figure 1 shows these measures of college affordability by state in 2017. For each state, the bar on the left shows the average net price for in-state students at public higher education institutions.[31] The bar on the right shows the median household income. The chart is sorted by the gold line, which divides average net price by the median household income. States that have more affordable public colleges – like California, New York, and Hawaii – appear on the right side of the chart. California, for example, was the state with the most affordable public colleges in 2017. The average net price at public institutions was $10,111 per year, which represented 14.1 percent of the state’s median household income of $71,805. On the other end of the spectrum, Vermont had the least affordable public colleges. The average net price of $17,363 represented 30.2 percent of the median household income of $57,513. The net price of public colleges in Vermont was higher than in California and the median income was lower, making public higher education substantially less affordable.

Figure 1 – When comparing average net price to median family income, college affordability varies by state[32] |

| Source: IPEDS; U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Note: all dollar figures are inflation-adjusted using the CPI to be in 2017 dollars. |

While public colleges vary in affordability for in-state students, schools in all states often use out-of-state and foreign students to increase revenues. These students typically pay higher tuition prices than in-state students and typically receive fewer tuition discounts in the form of institutional or other types of financial aid. Public institutions, especially more selective publics, have used this source of revenue to offset declines in state funding, which in many cases has resulted in decreasing enrollments of low-income and underrepresented minority students. [33] The use of nonresident enrollment to stabilize revenue may also undercut a state college’s mission of supporting the educational needs of state residents. This tension between financial stability and institutional mission is an important consideration for policymakers and governing boards considering tuition freezes as well as the impact that changes in appropriations may have on an institution’s tuition setting behavior.

The complexities of state financial aid policies

In combination with tuition and appropriations, states’ financial aid policies can have an important impact on higher education affordability and equity of access. States typically allocate their grant aid programs using one or a combination of two criteria – students’ academic merit and students’ financial need. Over the last 20 years, states have increased the amount of money spent on grant aid per student, and an increasing share of those funds are distributed based on students’ academic merit. Between academic years 1996-97 and 2016-17, average state grant aid per student has increased by nearly 58 percent – from $520 per student to $820 per student. Over that same time period, the share of state grant aid allocated based on students’ academic merit has increased from 15 percent to 24 percent.[34]

Most scholars agree that merit aid programs disadvantage lower-income students and students of color and that shifting funds from need-based grant programs to merit-based programs likely widens existing enrollment gaps by income and race.[35] Moreover, merit-based programs may lead to higher tuition prices,[36] possibly dissuading low-income students from applying in the first place. Need-based grants, however, increase the likelihood that lower-income students will enroll in college and improve their chances of graduating.[37]

However, aid alone may not be the answer. Recent research suggests that increased Pell Grant awards did not improve persistence and completion among community college students in Wisconsin,[38] although other research suggests increased need-based aid may improve completion at public four-year colleges in Texas[39] and Florida.[40] A synthesis of this body of research suggests the complexity of applying for need-based programs is likely to hinder their effectiveness, and states should consider simplifying their grant programs.[41] Moreover, for students already enrolled, tying their funding to maintaining a certain GPA appears to provide incentives to improve outcomes.[42]

Additional research has examined more robust programs that award aid coupled with advising, mentoring, or counseling services. These targeted interventions appear to result in higher persistence and completion among low-income individuals.[43] This serves as an important reminder that the alignment of state higher education finance policies is necessary. Need-based grants may not be sufficient to improve student outcomes on their own; however, when coupled with increased appropriations, schools are more likely to have the necessary resources to provide additional student services to needy students.

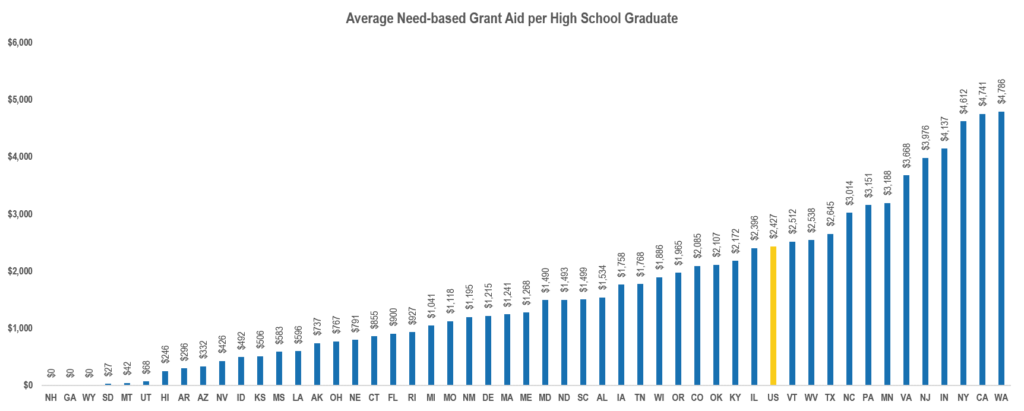

Figure 2 shows one way of comparing need-based grant aid across states. Rather than dividing need-based grant aid by the number of college students – since the amount of aid provided may affect a student’s decision to enroll – we divide by the number of high school graduates in the state. Three states – Washington, California, and New York – provide over $4,500 in need-based grant aid per high school graduate. Not surprisingly, these states also have among the most affordable public institutions, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2 – In 2017, some states provided over $4,000 in need-based grant aid per high school graduate, while others provided little to none |

| Source: NASSGAP, NCES Common Core of Data & WICHE Knocking at the College Door report. Note: All dollar figures are inflation-adjusted using the CPI to be in 2017 dollars. |

The amount of aid allocated is an important factor in achieving equity of access to a state’s public colleges. However, the process for allocating that aid can also impact equity, especially the timing of the grants and the eligibility criteria used to award them. Many states utilize “first-come, first-served” aid application processes, which require students to apply for aid before they finish their applications or make their decisions about where to attend. Students who apply for aid early in the process are more likely to receive aid and receive aid in higher amounts than students who apply later in the process.[44] This type of system inherently favors students with more knowledge of the college application and the financial aid processes, as well as those with parental support and involvement. As such, low-income and first-generation students may not maximize the amount of aid they receive, or may miss out receiving any state aid.

In many states there is a misalignment between admissions and FAFSA deadlines resulting in some students having to make application and enrollment decisions prior to obtaining their financial aid award. Without knowing their aid award, students do not know the net price they will pay and thus may not apply due to the perceived price which is the published tuition and fees. These misaligned deadlines may favor wealthier students, for whom money is less of an issue, and those with more college knowledge, who may have a better understanding of their likely net price. Tennessee provides an example of how state policy can remedy this misalignment. As part of its goal to increase college attainment, the state has created the Tennessee FAFSA Frenzy which works with schools and communities to facilitate high school seniors’ completion of the FAFSA by the state’s aid application deadline of February 1.[45] In this way, Tennessee stymies the potential deleterious effects of an early aid application deadline and also provides students with their total aid package earlier which gives students more time to consider their postsecondary options.

States must also decide what eligibility criteria to set for both merit and need-based grant aid. Grant aid programs in many states require students to be enrolled full-time or to be recent high school graduates in order to be eligible for aid. These rules naturally exclude part-time students and adult students, who are more likely to be lower-income or from an underrepresented group. For instance, Georgia’s Hope Scholarship, which awards aid based on high school grades, naturally excludes adult students who do not apply to college directly from high school. For need-based aid, students typically must attend full time to receive full benefits. For example, in Minnesota, part-time students have their award prorated based on the number of credits. However, the parent or student contribution used in the award formula is not reduced if the student takes fewer credits, so a student who is eligible for an award with a full-time course load may be expected to pay more out-of-pocket at a lower enrollment level.[46]

Among the most significant need-based grant aid programs are states with promise programs or free-college programs. Tennessee and New York have two of the most robust and well-known programs. New York’s Excelsior Scholarship, for example, provides free tuition for eligible students pursuing four-year degrees at CUNY and SUNY campuses with a family income under $75,000. This, however, is a “last-dollar” program, meaning that it provides funding for tuition costs after all other grants and scholarships – federal, state, institutional – are taken into account. Last-dollar programs are less likely to benefit many low-income students than their more moderate-income peers.[47] The NY Excelsior Scholarship, for instance, can only be used for tuition and fees, unlike federal student aid dollars which can help students buy books and pay for housing and food. Under last-dollar state programs, federal sources of aid must first be applied to tuition charges, thus precluding students from using last-dollar funds to cover the full cost of attending college (i.e., housing, books, or meals). In these cases, low-income students whose tuition charges are largely covered by federal awards likely receive less or no aid from last-dollar state programs, while moderate-income students likely receive more.[48] These equity implications are important for policymakers to consider when designing legislation.[49]

Promise programs have become increasingly widespread and range in size from individual towns to entire state. These programs also take many forms and include both first- and last-dollar awards. Although the exact structure varies extensively, the general premise is that promise programs typically cover the full price of tuition.[50] Promise programs are more likely to improve retention and completion rates when the funding provided to low income students is packaged with other support services, like advising and mentoring support. Tennessee’s Promise Scholar Program, for example, includes an advisory component. The state also launched Tennessee Reconnect, which grants last-dollar funding specifically for adults to attend public community colleges for free and especially targets veterans and active-duty service members. Due to the variation in programs, the effectiveness of promise programs, generally, has not been fully evaluated.[51]

One key benefit of promise programs is the “free” college messaging. Advocates for such programs suggest that the free college message changes the mindset of individuals who would have been less likely to enroll in college. By making the price of college a non-factor, students may be more likely to envision college as a more certain part of their future.[52] However, a recent simulation study suggests that free community college may draw students away from four-year programs and decrease their likelihood of eventually completing a four year degree.[53] This study is supported by previous research that suggests the Adams Scholarship in Massachusetts caused students to enroll in lower quality public institutions and thus complete their degrees at lower rates.[54] The potential benefits of “free” college messaging must be balanced with the potential unintended consequences of such programs. Policymakers should consider both sides of the coin as they strategically align state funding policies.

Just as “free” college programs have the potential to concentrate enrollment in certain institutions or sectors, the design of state financial aid programs may expand or limit institutional choice. For example, 42 of 50 states allow students to use state need-based grants at private institutions, and the proportion of state need-based dollars that go to private institutions ranges from less than one percent to more than 80 percent.[55] In this way, the design of state aid programs can either facilitate choice in college enrollment and expand a student’s options, or funnel students into specific colleges. Research also shows that large state need-based grants increase the diversity of institutions low-income students attend, including increasing their enrollment at in-state four-year institutions.[56] State policymakers should be clear about the intended goals of their higher education financing strategy and build policy around that. The utility between concentrating access among a small group of institutions or broadening student choice will depend on each state’s postsecondary market and other finance-related policies.

Strategically aligning appropriations, tuition setting, and financial aid programs

Although much of the conversation about state financing of public colleges since the Great Recession has focused on undoing dramatic budget cuts, restoring higher education funding is not sufficient. Investment in higher education has numerous public and private returns; however, the returns vary across institutions. For example, students’ earnings vary by institution type,[57] as do the expected tax revenues derived from those earnings.[58] From public financing and state economic perspectives, it makes sense to increase postsecondary attainment. Having additional college-trained workers results in more economic activity, a higher tax base, and less spending of state dollars on social services targeted towards the needy. However, targeting public investment efficiently requires a deliberate alignment of multiple higher education strategies.

An effective strategy must first recognize the heterogeneity that exists within the postsecondary market. The cost to produce a credential and the efficiency of degree production varies across institution types. Institutions that produce credentials efficiently or that are particularly effective at graduating students are poised to provide large returns to state investment. For example, public minority serving institutions appear to be more effective at producing college graduates than private minority serving institutions.[59] There is also evidence that public master’s institutions are largely cost efficient and represent an opportunity to benefit from economies of scale in undergraduate training.[60] States would benefit from targeting funding towards these cost-effective public options in order to improve overall attainment.

Of course, before investments are made, state leaders must assess the current financial health of their postsecondary system as a whole as well as the health of individual colleges and campuses. Current funding policies may be disproportionately harming some institutions. For example, Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs) see disproportionate decreases in funding under performance-based funding policies.[61] In order to strategically invest in higher education, state leaders must assess the unique financial situations of their colleges to better understand where public dollars can maximize opportunities for students.

Similarly, cost-effectiveness varies across programs that seek to provide opportunities to historically underserved students and thus close equity gaps. For example, state aid dollars appear to have the largest impact on attendance for low-income students,[62] while findings from the evaluation of the HAIL (High Achieving Involved Leader) Scholarship at University of Michigan (UM), which guarantees four years of free tuition and fees at UM for lower-income Michigan residents, found disproportionate effects for lower-income rural students and those living farther from the university.[63] If reducing the needs for social welfare programs and increasing the tax base are important state goals, helping low-income students access postsecondary options and eventually earn a living wage should be part of the strategy. Moreover, as states consider the heterogeneous effects that aid programs have on specific populations, they can tailor their strategies to improve access and attainment. While increasing overall higher education funding will help achieve this goal, strategically aligning finance policy to give historically underserved students the best chance at postsecondary success is a more effective way to reach an attainment goal.

Faced with limited funds, policymakers are often faced with a trade-off between increasing aid programs and increasing appropriations. This mirrors the point made above, that states must increase access to historically underserved students, but that access must be to quality institutions. Research suggests that a state legislature with more professional staff is more likely to increase need-based aid rather than delegating the responsibilities of financing low-income students to colleges via increased appropriations.[64] Additionally, the decision to fund appropriations, need-based aid, or merit-based aid appears to be dominated by political influences rather than a strategic alignment between appropriations and aid programs.[65] We suggest that state politicians rely more heavily on legislative staff and state education officials for guidance on strategic postsecondary investments.

The case of Virginia

The State Council of Higher Education in Virginia (SCHEV) is one example of a state that has proposed a strategic alignment in its FY2020 budget. The proposal seeks funds to limit tuition increases, provide additional student financial aid, and support institutional excellence.[66] Specifically, SCHEV’s budget and policy recommendations include creating a separate fund to partially offset faculty salary increases, helping Virginia public colleges remain competitive with institutions in other states and ensuring high-quality public options. This fund is similar to direct appropriations, but it is explicitly earmarked for faculty recruitment and retention. Earmarked funds are also allocated through the Higher Education Equipment Trust Fund (HEETF). HEETF dollars are allocated to campuses depending on their needs in order to ensure each college is equipped to serve its region and unique student population. The budget also calls for increases in state student aid allocations to certain public colleges. Virginia colleges have their own tuition-setting authority, with some restrictions on the use of tuition revenue to subsidize out-of-state students, and the Council monitors enrollment trends to ensure lower-income students have opportunities to access all institutions. SCHEV recommends the state provide additional funds to schools with decreasing student populations, to help buffer loss of overall revenue and thus potential institutional aid dollars, as well as to schools with noticeable decreases in lower-income students under the premise that additional resources will enable institutions to lower the financial barriers lower-income students face and thus increase access for these individuals. Additionally, student aid allocations are targeted towards institutions based on the average level of need met, and each institution has a state-identified minimum.

The more general Tuition Assistance Grant (TAG) program, aimed at lower-income students, has included a special allocation for seniors planning to enter the teaching profession. Because this award does not come until the final year of schooling, its incentive power appears to be diminished. SCHEV has recommended ending this program and redirecting the dollars into the general TAG fund in order to increase the maximum grant awarded in the first year. The Council notes that other policies have already been implemented to address the teacher shortage and the current use of TAG dollars is duplicative.

SCHEV’s overall recommendation is to increase state funding to public higher education. Such an increase would benefit lower-income and underrepresented minority students’ access to quality postsecondary opportunities. However, SCHEV also recommends explicit strategies to align various postsecondary finance policies including state financial aid programs, general and earmarked appropriations, and tuition-setting policies (and the restrictions that accompany tuition revenue spending). This focus on all three aspects of higher education funding is intended to help institutions maintain their capacity to serve students and provide a high-quality education while simultaneously preserving affordability for all residents and increasing opportunities for historically underserved groups.

Accountability as a complement

Other states have used accountability measures to maintain the alignment of these three methods. The principal-agent relationship that exists between state government and public colleges underscores the logic behind regulatory policy being tied to postsecondary financing. States create “contracts,” or accountability measures, that guide the behaviors of public colleges to align with state goals. The effectiveness of these policies, however, hinges on design. For example, evidence from performance-based funding policies suggests that tying accountability directly to funding may create perverse incentives for colleges to game the system, such as colleges decreasing access for historically underserved students who may have a lower likelihood of graduating.[67]

Some states have used accountability policies to align financing and improve efficiency. Often, however, these are not tied to an institution’s funding. Rather, states rely on public reporting to hold colleges accountable to legislators and residents. This approach to accountability may help eliminate incentives for nefarious gaming and provide general guiding principles that reinforce the mission of colleges. In Ohio, public institutions are required to report how improved administrative efficiencies are directly benefiting students through increased affordability.[68] These reports are part of a holistic strategy aimed at improving efficiencies, decreasing costs to students, and maintaining quality. While these practices cannot make up for underfunded appropriations or financial aid programs, they can add public pressure to keep the three financial levers aligned.

Recommendations for improving alignment

Here we have mapped out what is known about three key areas of postsecondary finance: state appropriations, tuition-setting authority, and state financial aid programs. The alignment of these programs can help reduce inefficiencies and maximize the benefits of public higher education spending for historically underserved students. Alignment can improve access and attainment for these students and stands to improve the economic outlook for states. Building on the literature and the state examples, we have four suggestions for improving the alignment of finance policies.

First, developing an overarching plan is important to develop a coherent vision and to build policy around this. As discussed in our previous policy brief on north star goals, identifying a goal and coalescing stakeholders to reach this goal can move a policy agenda forward[69]. Similarly, we suggest that an overarching finance goal (or goals), should be used to bring stakeholders together and discuss the multifaceted approach to public higher education funding. The decisions around each financial lever are often made at different times during the legislative process and by different groups.[70] The structure and timing of these decisions lends itself to inefficiencies in the overall financing approach. We suggest not only gathering decision makers and stakeholders to develop a comprehensive strategy, but also to rely on the expertise of state higher education governing bodies, such at the State Council for Higher Education of Virginia.

Second, states must consider the contextual factors that make their state unique. The adoption, diffusion, and state-to-state learning has been well documented across a range of higher education policy issues.[71] However, evidence suggests that the effectiveness of state higher education policy is deeply rooted in economic, social, and political factors.[72] In order for states to ensure equity in access and opportunity and improve attainment rates for historically underserved students, they must align finance policies with their current and changing demographics, higher education structure (e.g., governance structure or public-private mix of institutions), and fiscal situation. While restoring postsecondary funding to its pre-recession levels is important for maintaining quality and access, the strategic use of those dollars in relation to state needs is important. The policy mix and specific alignment strategy should vary across states. Although looking to other states as examples of strategies may be helpful, it is important for leaders to evaluate these strategies within the context of their state.

Third, it is important for states to avoid duplicative efforts. Policymakers should consider how their strategies interact with federal policies. For example, last-dollar promise programs that only cover the tuition remaining after Pell grants do little to expand opportunities for lower-income students who are often still unable to cover the full cost of attendance, which includes housing, food, and books. For states with low sticker prices, the Pell grant may already serve this purpose. The example from California where the Student Centered Funding Formula shows us that aligning tuition-setting, state financial aid programs, and funding policies can eliminate duplicative efforts and may improve efficiency.

Finally, states must avoid goal conflict within policies. Implementing funding policies, such as performance-based funding, that decrease state appropriations to minority-serving institutions will undercut efforts to improve access as these institutions will be less capable to serve enrolled students and the educational quality may be affected. Moreover these policies have been shown to incentivize colleges to exclude lower-income and minority students. If the state has a goal to improve opportunities and student outcomes for underrepresented minority students, performance-based funding may limit their opportunities. Even if coupled with state financial aid, these students may be relegated to underfunded and lower-quality institutions. When funding, financial aid, and tuition-setting policies are designed to avoid goal conflict, access and attainment can be improved for lower-income and underrepresented minority students.

Conclusion and remaining questions

Policies related to appropriations, tuition setting, and state financial aid impact students’ decision to enroll, likelihood of success in college, and long-term economic success. The interplay between these policies demonstrates the inability of any one policy to be a panacea for postsecondary finance issues. Here we call for an explicit focus on the strategic alignment of these policies for two overarching reasons: first, aligning policies to work cooperatively stands to bring greater levels of efficiency to an already underfunded sector; second, using multiple financial levers to impact students across the lifecycle of applying to and completing college can improve overall attainment, help close persistent racial and income-based gaps, and improve the economic outlook for both students and the state. While increasing postsecondary funding is important, targeting these investments strategically will maximize the benefits of public dollars.

This policy memo describes what is currently known about the effects of each lever. Lowering tuition may help reduce sticker shock for some students; however, the net price that students eventually pay appears to have a larger impact on enrollment and persistence. The use of state financial aid can be an effective tool to reduce net price and increase the enrollment of historically underserved students. But a high tuition price and a complicated financial aid system dampens these effects. Moreover, lowering the barrier to entry by sacrificing quality does not serve students well and may not improve their outcomes. In fact, colleges have a greater impact when increased appropriations are used to improve educational offerings rather than to lower tuition. It is important for states to maintain adequate funding so colleges can serve their students and target aid programs to those least likely to enroll and persist. While a great deal of attention has been paid to restoring funding to pre-recession levels, we believe this restoration should be done simultaneously with a purposeful and strategic alignment of financial levers to maximize the benefits of public higher education. Although there is a wealth of information on each lever, there are still important questions researchers must address, including the examination of the strategic alignment. We pose some of these questions below:

- To what extent does the alignment of appropriations, tuitions setting, and financial aid increase access and attainment?

- Which states take a strategic and holistic approach to appropriations, grant aid, and tuition? How are those plans developed and implemented and what are their essential components?

- Which states prioritize year-to-year stability in funding? What are the essential components of these stability policies and how are these policies sustained?

- What are the effects of changes in state aid programs on tuition, affordability, and institutional spending?

- Do state-imposed limits on tuition increases impact the enrollment of nonresident students?

- How do higher education governance structures impact the alignment and effectiveness of these three levers?

- How do other state policies (such as authorization, quality assurance, and consumer protection) interact with the three funding levers?

Endnotes

- Jennifer A. Delaney and William R. Doyle, “State Spending on Higher Education: Testing the Balance Wheel over Time,” Journal of Education Finance (2011): 343-368, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23018116. ↑

- Douglas A. Webber, “State Divestment and Tuition at Public Institutions,” Economics of Education Review 60 (2017): 1-4, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2017.07.007 ↑

- While measures of quality in higher education may difficult to ascertain, we believe retention, completion, loan repayment, and employment rates can serve as useful proxies. When schools have sufficient resources to serve their student populations, these measures would be expected to increase, and thus we would consider that to be a higher quality educational offering. Thus quality reflects the ability of a school to provide useful and effecting instruction as well as the necessary ancillary supports for students to succeed. ↑

- David J. Deming and Christopher R. Walters, The Impact of Price Caps and Spending Cuts on US Postsecondary Attainment, Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017, https://doi.org/10.3386/w23736. ↑

- Rajashri Chakrabarti, Nicole Gorton, and Michael F. Lovenheim, The Effect of State Funding for Postsecondary Education on Long-Run Student Outcomes, Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017, http://conference.iza.org/conference_files/WoLabConf_2018/chakrabarti_r26265.pdf. ↑

- Sandy Baum, Michael S. McPherson, Breno Braga, and Sarah Minton, Tuition and State Appropriations: Using Evidence and Logic to Gain Perspective, Washington: Urban Institute, 2018, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/tuition-and-state-appropriations. ↑

- James C. Hearn, Outcomes-Based Funding in Historical and Comparative Context, Lumina Issue Papers, Indianapolis: Lumina Foundation for Education, 2015, https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/resources/hearn-obf-full.pdf.Daniel T. Layzell, “State Higher Education Funding Models: An Assessment of Current and Emerging Approaches,” Journal of Education Finance 33, no. 1 (2007): 1-19, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40704312. ↑

- Martha Snyder and Brian Fox, Driving Better Outcomes: Fiscal Year 2016 State Status and Typology Update, Washington: HCM Strategists, 2016, http://hcmstrategists.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2016-Report-Update-WEB.pdf. ↑

- James C. Hearn, Outcomes-Based Funding in Historical and Comparative Context, Lumina Issue Papers, Indianapolis: Lumina Foundation for Education, 2015, https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/resources/hearn-obf-full.pdf. ↑

- Tiffany Jones, Sosanya Jones, Kayla C. Elliott, L. Russell Owens, Amanda E. Assalone, and Denisa Gándara, Outcomes Based Funding and Race in Higher Education, Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49436-4. ↑

- Arkansas, Kentucky, Nevada, Ohio, Virginia, Washington, Oregon, and Pennsylvania include weights for underrepresented minority students; Arkansas, Louisiana, Montana, Ohio, Tennessee, and Maine include weights for adult students; Montana, New York, and Oregon include weights for military veterans. ↑

- Amy Y. Li and Alec I. Kennedy, “Performance Funding Policy Effects on Community College Outcomes: Are Short-term Certificates on the Rise?” Community College Review 46, no. 1 (2018): 3-39, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0091552117743790. ↑

- Nicholas Hillman and Daniel Corral, “The Equity Implications of Paying for Performance in Higher Education,” American Behavioral Scientist 61, no. 14 (2017): 1757-1772, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0002764217744834.Chris. Birdsall, “Performance Management in Public Higher Education: Unintended Consequences and the Implications of Organizational Diversity,” Public Performance & Management Review 41, no. 4 (2018): 669-695, https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2018.1481116. ↑

- California Community Colleges. “Student Centered Funding Formula.” Accessed August 1, 2019: https://www.cccco.edu/About-Us/Chancellors-Office/Divisions/College-Finance-and-Facilities-Planning/Student-Centered-Funding-Formula. ↑

- Program-Based Funding, Cal. EDC § 84750 (2019), https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=EDC&division=7.&title=3.&part=50.&chapter=5.&article=2 ↑

- Sheila A. Slaughter and Gary Rhoades, Academic Capitalism and the New Economy: Markets, State, and Higher Education, Baltimore, Maryland: JHU Press, 2004, https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/academic-capitalism-and-new-economy. ↑

- Colleen Flaherty, “Accreditation Risk From Alaska Cuts,” Inside Higher Education, July 10, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/07/10/u-alaskas-accreditor-warns-funding-cuts-could-threaten-systems-status. ↑

- John Armstrong, Andy Carlson, and Sophia Laderman, The State Imperative: Aligning Tuition Policies with Strategies for Affordability, Boulder, CO: State Higher Education Executive Officers, 2017, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED589744. ↑

- Ethan Henley, “Sticker Shock: The Rising Cost of College,” Journal of Higher Education Management 29, no. 1, (2014): 16-21, http://www.aaua.org/journals/pdfs/JHEM-Vol29-2014.pdf. ↑

- Drew Allen and Gregory C. Wolniak. “Exploring the Effects of Tuition Increases on Racial/Ethnic Diversity at Public Colleges and Universities,” Research in Higher Education 60, no. 1 (2019): 18-43, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9502-6. ↑

- Amy Li and Jen Mishory. “Financing Institutions in the Free College Debate,” New York, NY: The Century Foundation, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/report/financing-institutions-free-college-debate/. ↑

- Elizabeth Redden, “DACA Lives, but for How Long?” Inside Higher Education, March 5, 2018, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/03/05/daca-continues-now-colleges-and-students-face-uncertainties. ↑

- Dylan Conger and Lesley J. Turner, The Impact of Tuition Increases on Undocumented College Students’ Attainment, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2015, https://doi.org/10.3386/w21135. ↑

- James C. Hearn, Carolyn P. Griswold, and Ginger M. Marine, “Region, Resources, and Reason: A Contextual Analysis of State Tuition and Student Aid Policies,” Research in Higher Education 37, no. 3 (1996): 141-178, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01730117. ↑

- William R. Doyle, “The Politics of Public College Tuition and State Financial Aid,” The Journal of Higher Education 83, no. 5 (2012): 617-647, https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2012.11777260. ↑

- Vincent Badolato, “Getting what You Pay for: Tuition Policy and Practice,” Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission on Higher Education, 2008, https://www.wiche.edu/info/gwypf/badolato.pdf. ↑

- Stephen Burd, “Undermining Pell: Volume III: The News Keeps Getting Worse for Low-Income Students,” Washington, DC: New America, 2016, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/policy-papers/undermining-pell-volume-iii/. ↑

- Christine Jacobs and Sarah Whitfield, “Beyond Need and Merit: Strengthening State Grant Programs,” Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2012, https://www.brookings.edu/research/beyond-need-and-merit-strengthening-state-grant-programs/. ↑

- Dustin Weeden, “Hot Topics in Higher Education: Tuition Policy,” Washington, DC: National Conference for States Legislatures, 2015, https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/83158. ↑

- Texas Code § 56.011, https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/ED/htm/ED.56.htm. ↑

- To calculate this average net price, we first calculate an enrollment-weighted average of the net price in two-year and four-year institutions separately. We then average the two-year and four-year net prices – weighting by the national share of enrollment in two- and four-year institutions – to get a single average net price. We weight by the national share of enrollment to avoid having the enrollment mix in the state affect the net price (e.g. having states with a high share of students attending two-year institutions appear to be especially inexpensive). The resulting number should be thought of as the average net price in the state if the state had the national average mix of enrollment in two- and four-year institutions. ↑

- Note: Average net price reflects what the average net price would be if the state had the national enrollment mix of two-year and four-year institutions. ↑

- Ozan Jaquette and Bradley R. Curs, “Creating the Out-of-State University: Do Public Universities Increase Nonresident Freshman Enrollment in Response to Declining State Appropriations?” Research in Higher Education 56, no. 6 (2015): 535-565, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-015-9362-2.Ozan Jaquette, Bradley R. Curs, and Julie R. Posselt, “Tuition Rich, Mission Poor: Nonresident Enrollment Growth and the Socioeconomic and Racial Composition of Public Research Universities,” The Journal of Higher Education 87, no. 5 (2016): 635-673, https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2016.0025. ↑

- Sandy Baum, Jennifer Ma, Matea Pender, and CJ Libassi. “Trends in Student Aid, 2018. Trends in Higher Education Series,” New York, NY: College Board Advocacy & Policy Center, 2018, https://research.collegeboard.org/trends/student-aid/resource-library. ↑

- Bridget Terry Long and Erin Riley, “Financial aid: A Broken Bridge to College Access?” Harvard Educational Review 77, no. 1 (2007): 39-63, https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.77.1.765h8777686r7357. ↑

- Nathan E. Lassila, “Effects of Tuition Price, Grant Aid, and Institutional Revenue on Low-Income Student Enrollment,” Journal of Student Financial Aid 41, no. 3 (2011), https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4191/2a2987847c375aab5ab00f0f55cef28397bc.pdf. ↑

- Susan M. Dynarski, “Does Aid Matter? Measuring the Effect of Student Aid on College Attendance and Completion,” American Economic Review 93, no. 1 (2003): 279-288, https://doi.org/10.1257/000282803321455287.Gabrielle Fack and Julien Grenet, “Improving College Access and Success for Low-Income Students: Evidence from a Large Need-Based Grant Program,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7, no. 2 (2015): 1-34, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130423. ↑

- Drew M. Anderson and Sara Goldrick-Rab, “Aid After Enrollment: Impacts of a Statewide Grant Program at Public Two-Year Colleges,” Economics of Education Review 67, December (2018): 148-157, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.10.008. ↑

- Jeffrey T. Denning, Benjamin M. Marx, and Lesley J. Turner, “ProPelled: The Effects of Grants on Graduation, Earnings, and Welfare,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11, no. 3 (2019): 193-224, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20180100. ↑

- Benjamin L. Castleman and Bridget Terry Long, “Looking Beyond Enrollment: The Causal Effect of Need-Based Grants on College Access, Persistence, and Graduation,” Journal of Labor Economics 34, no. 4 (2016): 1023-1073, https://doi.org/10.1086/686643. ↑

- Susan Dynarski and Judith Scott-Clayton, “Financial Aid Policy: Lessons from Research.” Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2013, https://doi.org/10.3386/w18710. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Lindsay C. Page, Stacy S. Kehoe, Benjamin L. Castleman, and Gumilang Aryo Sahadewo, “More than Dollars for Scholars the Impact of the Dell Scholars Program on College Access, Persistence, and Degree Attainment,” Journal of Human Resources 54, no. 3 (2019): 683-725, https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.54.3.0516.7935R1.Susan Scrivener and Michael J. Weiss, “More Graduates: Two-Year Results from an Evaluation of Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) for Developmental Education Students,” Available at SSRN 2393088, 2013, https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2393088.Josh Angrist, Sally Hudson, and Amanda Pallais. “Evaluating Econometric Evaluations of Post-Secondary Aid,” American Economic Review 105, no. 5 (2015): 502-07, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20151025. ↑

- Mary Feeney and John Heroff, “Barriers to Need-Based Financial Aid: Predictors of Timely FAFSA Completion Among Low-Income Students,” Journal of Student Financial Aid 43, no. 2 (2013), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1018067.pdf. ↑

- Mary Nelle Karas, Amanda Klafehn, and Courtney Souter, “Tennessee’s FAFSA Frenzy: Data, Communications, and Statewide Partnerships,” Nashville, TN: Tennessee Higher Education Commission, 2018, https://www.tbr.edu/sites/default/files/media/2018/10/5%20FAFSA%20Presentation_Equity%20Conference_10012018.pdf. ↑

- Minnesota Office of Higher Education, “Minnesota State Grant,” Accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.ohe.state.mn.us/mPg.cfm?pageID=138. ↑

- Casey Bayer, “What Does Free College Really Mean?” Harvard Graduate School of Education, Accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/17/01/what-does-free-college-really-mean. ↑

- Sara Goldrick-Rab, Paying The Price: College Costs, Financial Aid, and the Betrayal of the American Dream, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2016, https://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/P/bo24663096.html. ↑

- The NY Excelsior Scholarship also requires students to remain a NY resident after college or the awarded dollars are converted into state-backed loans which must be repaid. Students who have more family resources may be more financially capable of turning down out-of-state opportunities and absorbing additional loans. This conversion to loans may have additional equity implications. ↑

- Laura W. Perna and Elaine W. Leigh, “Understanding the Promise: A Typology of State and Local College Promise Programs,” Educational Researcher 47, no. 3 (2018): 155-180, https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0013189X17742653. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Madeline St. Amour, “Study Minimizes the Impact of Free Community College,” Inside Higher Ed, September 6, 2016, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/09/06/study-plays-down-potential-impact-free-community-college-four-year-graduation. ↑

- Christopher Avery, Jessica Howell, Matea Pender, and Bruce Sacerdote, “Policies and Payoffs to Addressing America’s College Graduation Deficit” BPEA Conference Draft, Fall 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Avery-et-al_conference-draft.pdf. ↑

- Sarah R. Cohodes and Joshua S. Goodman, “Merit Aid, College Quality, and College Completion: Massachusetts’ Adams Scholarship as an In-Kind Subsidy,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6, no. 4 (2014): 251-85, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.6.4.251. ↑

- “48th Annual Survey Report on State-Sponsored Student Financial Aid,” Washington, DC: National Association of State Student Aid and Grant Programs, https://www.nassgapsurvey.com/survey_reports/2016-2017-48th.pdf. ↑

- Laura W. Perna and Marvin A. Titus, “Understanding Differences in the Choice of College Attended: The Role of State Public Policies,” The Review of Higher Education 27, no. 4 (2004): 501-525, http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2004.0020. ↑

- Kristin Blagg and Erica Blom, “Evaluating the Return on Investment in Higher Education: An Assessment of Individual-and State-Level Returns,” Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2018, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED592627. ↑

- Jennifer Ma, Matea Pender, and Meredith Welch, “Education Pays 2016: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society. Trends in Higher Education Series,” New York, NY: College Board, 2016, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED572548. ↑

- G. Thomas Sav, “Minority serving college and university cost efficiencies.” Journal of Social Sciences 8, no. 1 (2012), https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v5n3p26. ↑

- Marvin A. Titus, Adriana Vamosiu, and Kevin R. McClure, “Are Public Master’s Institutions Cost Efficient? A Stochastic Frontier and Spatial Analysis,” Research in Higher Education 58, no. 5 (2017): 469-496, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-016-9434-y. ↑

- Nicholas Hillman and Daniel Corral, “The Equity Implications of Paying for Performance in Higher Education,” American Behavioral Scientist 61, no. 14 (2017): 1757-1772, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0002764217744834. ↑

- Lyle Mckinney, “An Analysis of Policy Solutions to Improve the Efficiency and Equity of Florida’s Bright Futures Scholarship Program,” Florida Journal of Educational Administration & Policy 2, no. 2 (2009): 85-101, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ930108.pdf. ↑

- Susan Dynarski, C. J. Libassi, Katherine Michelmore, and Stephanie Owen, “Closing the Gap: The Effect of a Targeted, Tuition-Free Promise on College Choices of High-Achieving, Low-Income Students,” Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018, https://doi.org/10.3386/w25349. ↑

- Robert C. Lowry, “Subsidizing Institutions vs. Outputs vs. Individuals: States’ Choices for Financing Public Postsecondary Education,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26, no. 2 (2015): 197-210, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv024. ↑

- Michael K. McLendon, David A. Tandberg, and Nicholas W. Hillman, “Financing College Opportunity: Factors Influencing State Spending on Student Financial Aid and Campus Appropriations, 1990 through 2010,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 655, no. 1 (2014): 143-162, Financing College Opportunity: Factors Influencing State Spending on Student Financial Aid and Campus Appropriations, 1990 through 2010. ↑

- State Council of Higher Education for Virginia, “FY 2020 Budget and Policy Recommendations for Higher Education in Virginia.” Accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.schev.edu/docs/default-source/Reports-and-Studies/2018-reports/fy2020budget-recommendations11918.pdf. ↑

- Kevin J. Dougherty, Sosanya M. Jones, Lara Pheatt, Rebecca S. Natow, and Vikash Reddy, Performance Funding for Higher Education. Baltimore, MD: JHU Press, 2016, https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/performance-funding-higher-education. ↑

- John Armstrong, Andy Carlson, and Sophia Laderman, The State Imperative: Aligning Tuition Policies with Strategies for Affordability, Boulder, CO: State Higher Education Executive Officers, 2017, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED589744. ↑

- Cindy Le, Elizabeth Davidson Pisacreta, James Dean Ward, and Jesse Margolis, “Setting a North Star: Motivations, Implications, and Approaches to State Postsecondary Attainment Goals,” New York, NY: Ithaka S+R, 2019, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.311539. ↑

- Dennis Jones, “Financing in Sync: Aligning Fiscal Policy with State Objective,” Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, 2003, https://www.wiche.edu/Policy/PolicyInsights/PoliciesInSync/JonesInsight.pdf. ↑

- T. Austin Lacy and David A. Tandberg, “Rethinking Policy Diffusion: The Interstate Spread of ‘Finance Innovations’,” Research in Higher Education 55, no. 7 (2014): 627-649, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-014-9330-2.Amy Y. Li, “Covet thy Neighbor or ‘Reverse Policy Diffusion’? State Adoption of Performance Funding 2.0,” Research in Higher Education 58, no. 7 (2017): 746-771, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-016-9444-9.James Dean Ward and William G. Tierney, “Regulatory Enforcement as Policy: Exploring Factors Related to State Lawsuits Against For-Profit Colleges,” American Behavioral Scientist 61, no. 14 (2017): 1799-1823, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0002764217744819. ↑

- Laura W. Perna, Joni E. Finney, and Patrick M. Callan, The Attainment Agenda: State Policy Leadership in Higher Education, Baltimore, MD: JHU Press, 2014, https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/attainment-agenda. ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.