Using Equity Data to Guide the Design and Implementation of the New General Education Curriculum at Ohio State

-

Table of Contents

- 1. Series Overview

- Introduction: Designing a new, equity-driven General Education Curriculum at Ohio State

- Part I: Adopting an inclusive and holistic approach to decision-making, design, and implementation

- Part II: Using data to guide the design process

- Part III: Paving the way to assess the impact of the new GE curriculum on academic equity

- Final Thoughts

- Appendix I: The Second Year Transformational Program (STEP)

- Acknowledgements

- Endnotes

- 1. Series Overview

- Introduction: Designing a new, equity-driven General Education Curriculum at Ohio State

- Part I: Adopting an inclusive and holistic approach to decision-making, design, and implementation

- Part II: Using data to guide the design process

- Part III: Paving the way to assess the impact of the new GE curriculum on academic equity

- Final Thoughts

- Appendix I: The Second Year Transformational Program (STEP)

- Acknowledgements

- Endnotes

1. Series Overview

In Fall 2020, the American Talent Initiative (ATI), an alliance of high-graduation-rate colleges and universities committed to expanding access and opportunity for low- and middle-income students, established its newest community of practice (CoP) focused on academic equity. Together, the 37 CoP members explore topics related to creating equitable academic communities. One such area of focus is how institutions can more effectively utilize data to enhance their equity-related projects. In January 2021, members participated in a webinar discussion on this topic, during which CoP representatives presented on how they have leveraged data in their academic equity work. This case study builds on a presentation given by Dr. Meg Daly, Professor at The Ohio State University, titled, “Using Data to Guide the Design and Implementation of the OSU’s New General Education Curriculum.”

Introduction: Designing a new, equity-driven General Education Curriculum at Ohio State

In 2017, Ohio State University (OSU) embarked on reimagining its General Education (GE) curriculum to build an educational experience that better supported the academic capacity and professional goals of its students and aligned with the university’s commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion. The process of redesigning the GE provided OSU with an opportunity for institutional reflection and self-study and engaged faculty in conversation about the needs and experiences of students. This process resulted in a new curricular program, launching in Fall 2022, that incorporates measurable goals tied to key intellectual and cognitive skills, showcases new and inclusive pedagogies and approaches to academic research, and foregrounds the intention of having students become “interculturally competent global citizens who can engage with significant aspects of the human condition in local, state, national, and global settings.”[1]

The current GE was first introduced at OSU in the 1980s. Each of the 12 academic colleges[2] across the university’s six campuses administers its own GE program. Despite variations in GE offerings across the colleges, the current GEs all require students to enroll in 45-65 credit hours across seven to ten subject areas. Revisions in the 1990s and early 2000s in some colleges added a focus on coursework related to social diversity and encouraged participation in study abroad, service learning, and cross disciplinary seminars.

These slight changes to the GE occurred against a backdrop of significant change in the OSU student profile. The current student body is more academically distinguished, more international, and more racially diverse than the student body of 1985. More students were interested in pursuing interdisciplinary academic programs, including double majors that spanned two colleges. Likewise, the faculty of 2015 and of 1985 differed significantly in their scholarship, with emerging emphasis on intersectional approaches to cultural studies and greater weight placed on global competencies within disciplines like business, engineering, and food, agriculture, and environmental sciences.

Not only was the GE no longer responsive to the university’s growing diversity and new directions of scholarship, but it also lacked cohesion across colleges and campuses. Course availability differed from one campus to the next, raising equity concerns across OSU’s main Columbus campus (~46,000 undergraduates currently enrolled) and its five regional campuses (undergraduate enrollments currently range from 600 at Wooster to 2,700 at Newark).

Importantly, there was no way to assess the curriculum’s effectiveness at providing an equitable, foundational education to its undergraduate students: no program-level goals existed against which faculty and staff could evaluate the curriculum.

The committee that initiated the revision to OSU’s approach to the GE aimed to integrate the changing perspectives and needs of the OSU community, and create a cohesive program with articulated goals. As we discuss below, the self-study and dialogue that accompanied the process of “reimagining General Education for OSU” brought several key priorities to the fore, which drove the approach and design of OSU’s re-imagined GE: 1) The GE should be an engine for building cultural competencies and educating students on issues of race, gender, and ethnic diversity, two areas considered critical components of an undergraduate education by faculty and students alike; 2) High-impact pedagogies like service learning, study away from campus, or integrating research and creative inquiry are highly valuable, but should be available and relevant to more of the student body, as there were marked differences in participation based on race, gender, and major, and; 3) The new GE should be a shared experience, inclusive of major and campus of enrollment.

In the sections below, we outline the key stages of our design and implementation of OSU’s new GE curriculum, focusing on how we used data at each stage to inform the process. In Part I, we provide an overview of the stages of GE design and implementation. Part II hones in on how the use of diverse data and perspectives guided these processes. In Part III, we conclude with a description of how OSU plans to use data to assess the new GE’s impact on student outcomes and equity.

Part I: Adopting an inclusive and holistic approach to decision-making, design, and implementation

Designing and implementing the new General Education curriculum at OSU has four key steps in the process:

Step 1: Recommendation from University Senate committee

The recommendation to overhaul the GE at OSU was made by the Council on Academic Affairs, a committee of the University Senate that included students, faculty, and staff from across OSU campuses. They recommended comprehensive, rather than incremental, changes, and for those changes to apply across all colleges and majors. This recommendation led to the formation of the design committee, which included students, faculty representing the colleges and campuses, and staff with expertise in curriculum design, digital education, and student academic support.

Step 2: Design committee works to develop GE with participation from each college

This newly-formed design committee used self study and comparative study of other programs as a starting point for the design process. This approach helped develop community and cohesion within the committee. The group quickly converged on the motto of the University—Education for Citizenship—as the guiding principle of this shared GE curriculum. As a result, a signature component of the new GE is a requirement for all students to take coursework that explores “Citizenship for a Just and Diverse World.”

The governance structure of Ohio State required that all plans be approved by each college. In most cases, this required discussion and then voting by representative bodies within a college. Rather than just presenting a final draft, college governance groups were engaged during development, and major changes were made at each stage to address the needs of the colleges. The principles guiding the changes were those of the initial charge: the GE was to be a coherent program, shared by all OSU undergraduates, with impactful, modern courses that provide opportunities for students to gain a foundational understanding of the diversity of disciplines and to dig deeper on some key topics, including citizenship. Among other changes, feedback from the colleges led to the development of a mechanism to increase the availability of “Integrative Practice” courses that include high impact pedagogies like education away, service-learning, interdisciplinary team-taught courses, instruction in a world language, and research and creative inquiry.

Step 3: Implementation of GE, with strong representation from different colleges and regional campuses

The implementation phase of the GE revisions relied on similar structures as the design phase. Implementation, like the design process, was faculty led, with co-chairs who represented different colleges. The implementation team included faculty, staff, and students, with strong representation from regional campuses. In this phase, a representative from Columbus State Community College (CSCC) joined the team to help OSU team members understand how the curriculum might impact OSU’s partnership with CSCC and its relationships with other two-year transfer partners.

Unlike the design phase, implementation planning worked primarily through subcommittees, with each group focusing on a specific issue. Academic advising staff and regional campus faculty participated in most of the committees, but each constituency also met in cross-committees that allowed them to share information and identify group-specific issues to spotlight for the full committee.

Step 4: Ongoing implementation

Although the implementation committee disbanded after submitting its final report in February 2020, a standing subcommittee of the University Senate’s Council on Academic Affairs, manages ongoing activities related to implementation. The composition of this subcommittee mirrors that of the design and implementation committees, including faculty from each college and the regional campuses and undergraduate students as voting members, with participation from academic advising, student services, the registrar’s office, and college governance groups.

Part II: Using data to guide the design process

The design committee (step 2 above) utilized data in a few different ways to inform the GE, including feedback from employers on desired attributes of graduates, exit surveys from graduating students, and institutional data on student enrollment patterns. In this section, we describe these data elements in greater detail:

- Surveys: Colleges had previously developed surveys of students, employers, and other stakeholders in response to other needs. By using data from previously administered surveys, the team was able to move more quickly in data collection and mitigate concerns of widespread “survey fatigue,” but this re-use may have limited the scope of the information gathered.

- Listening Sessions: The design process included listening sessions on each campus, with sessions on the Columbus campus that included department chairs and other leaders, which focused on either student or faculty ideas and concerns. More than 1,000 people provided feedback in the design and development phase. The faculty and student feedback led to the prioritization of cultural competencies as a key goal of the program and to the development of an emphasis on understanding race, gender, and ethnic diversity. The emphasis on race, ethnic, and gender diversity was an early suggestion in a faculty listening session that was amplified and promoted in subsequent discussions.

- University data sources: Members of the design committee queried existing institutional data as part of ongoing discussions, with an emphasis on using these data and the expertise of academic advising to understand how students navigate their GE curriculum. For example, it was evident from these data that many students took a burst of GE courses early in their tenure at OSU and then finished their GE coursework in their last few terms, with low engagement in GE coursework in the middle. Although OSU offers thousands of GE courses, and these courses span the curriculum and “level” of instruction from introductory to more advanced courses, only a small set of introductory courses received the vast majority of enrollments. Contrary to expectations, students in their third or fourth year on campus did not take advanced courses at higher rates than students in their first or second year on campus except when those courses overlapped with upper-year students’ majors.

The design committee made decisions based on information gleaned from these surveys, listening sessions, and university data. For example, cultural competence was on the radar of the design group from a stakeholder survey of employers, who identified the ability of students to work across communities and to function within teams as highly desired skills. Moreover, focus group discussions among students revealed that an exclusive and toxic culture within STEM gateway courses, largely attributed to the attitudes of fellow students, deterred many students from underrepresented groups—students of color and women—from pursuing STEM majors. Thus, the program goals for the revised GE emphasize cultural competence and inclusive team-building, and nearly all of the categories within the GE require that students explore the ethical and social dimensions of the discipline, be it history, science, art, or math.

The design committee also highlighted that disparities in the availability of courses and academic experiences for students on the regional campuses had the greatest potential to create inequities in opportunity across the university, as the regional campus student body is more racially and economically diverse, compared to Columbus. The regional campus cross-committee group (within the implementation team) identified key issues for the success of regional campus students in the new GE, including access to courses, availability of Integrative Practice courses, and local input on the “Bookend” seminars that launch and close the GE.

Beyond the implications for equity, maintaining equivalency between the regional campuses and Columbus has practical consequences because many students ultimately transfer to Columbus from the regional campuses and comparable experiences help with a seamless transition. Customization and support are important too, so that the GE curriculum has relevance and resonance for students on the regional campuses while they are there. Changes in the process of course approval, agreement on baseline availability of courses, and ongoing regional campus participation in the development of the content for the Bookend seminars addresses the most fundamental of these needs. Inclusive branding for the ePortfolio tool used in the GE features students and sights from each of the campuses to make clear that this is a GE for all Ohio State students.

Data also helped identify issues of equity in student participation in courses that involve high impact pedagogies such as service learning, study abroad, and independent research. An OSU working group participating in the Reinvention Collaborative’s Lamborn-Hughes Institute took up the issue, identifying discrepancies in participation across colleges and student demographics, highlighting that men—and particularly Black men—were less likely to take courses that involved high impact practices. Their data represents an important baseline against which we can evaluate the impact of the Integrative Practice courses within the GE. The definitions of the practices and rubrics created during the Lamborn-Hughes Institute were the nucleus for the guidance built by the implementation committee for Integrative Practice courses. The expectation that Integrative Practice courses be visible to students from historically excluded or underrepresented groups is made explicit in the documentation for these courses, and all Integrative Practice courses must articulate their plan for reaching diverse students before being approved.

Part III: Paving the way to assess the impact of the new GE curriculum on academic equity

We hope that the revised GE offers significant academic benefit to Ohio State students. We plan to track the achievement of these benefits through program-level assessments that will focus both on the academic content and the institutional aspirations embodied in the new GE. The plan for program assessment leverages the collaborative approach used throughout the process and relies on data analysis begun as part of the design and implementation phases. Our expectation is that consistent, ongoing assessment will allow OSU to see and respond to changes in student needs as they arise and pursue continued modification of the program to improve student and institutional outcomes. In this section, we outline key principles of the revised GE’s program structure and the accompanying program assessment process.

Principle 1: Creating a holistic GE program to enhance learning outcomes and support program assessment

The revised GE was conceptualized as a program, with program-level goals met by the summed experience a student has within their courses. The program will be evaluated through course-level assessment and through the Bookend seminar that closes the GE experience, which includes an ePortfolio of artifacts from GE courses and reflections about the coursework and GE pathways. The closing Bookend is being designed to support assessment of the program, with the course-level goals aligning closely with program goals. Ease of use in assessment was a key decision factor in choosing a platform for the ePortfolio.

Principle 2: Adopting a laddered approach to evaluating student learning outcomes

The structure of the revised GE, which includes foundational coursework within disciplines and then more advanced, topical coursework on interdisciplinary themes, allows OSU faculty and staff to evaluate progression in student understanding, as some learning goals are shared across disciplines and stages within the GE, and these relate directly to program goals. For example, two related course-level goals are that: 1) students are expected to recognize the social and ethical dimensions of individual disciplines within their foundational coursework, and then; 2) students are able to examine and critique these dimensions within their interdisciplinary theme coursework. These course-level goals correspond directly to the program-level goal to “examine, critique, and appreciate various expressions and implications of diversity, equity, and inclusion, both within and beyond US society.”[3] This laddered approach to GE course progression and goals allows us to localize changes that might need to be made, should students not meet program goals. Additionally, the sharing of goals across categories within the foundational coursework enables comparison between disciplines in terms of the attainment of the goals, which can provide rationale to enact changes or provide targeted support.

Principle 3: Using baseline data to track progress toward institutional goals related to student success

In addition to the learning goals for students, OSU has institutional goals for the student experience: greater engagement with the curriculum, more exciting and pedagogically engaging experiences within GE courses, and ease of transition between campuses and colleges. As is the case with the current GE, we will monitor patterns of course enrollment for the revised GE, with the goal of seeing greater breadth and depth in the array of courses being taken to satisfy the GE. The expectation is that greater availability and visibility of the Integrative Practice courses in the GE will promote student participation in these courses in ways that mirror the demographics of the institution so that these GE experiences can serve as springboards for equitable participation in additional high impact courses. GE coordinators will compare student participation data against baseline data collected by the OSU Lamborn-Hughes working group (mentioned above). In addition, they plan to improve identification and tracking of the courses that incorporate these high-impact practices.

The standing subcommittee will monitor ease of navigation using standard metrics like graduation rates, both for all students, and for students in specific demographic groups (race, major, campus of enrollment, etc.). Our program-level goal is to increase four-year graduation rates across demographic groups, but especially in places where a significant gap exists—historically excluded and underrepresented groups and students who change academic programs during their career. In addition to standard metrics, GE coordinators on campus intend to develop ways to understand the impact of the revised GE on students who change majors or transfer, using metrics for “excess credits” not applied to a degree requirement that have been developed through a Joyce-Foundation-supported effort to improve the academic experience of transfer students (see Appendix).[4] Because this is a university-wide effort, the university will be able to measure the new GE’s impact in all of the ongoing benchmarking and evaluation the university does for undergraduate student success.

Principle 4: Maintaining a focus on collaboration in course- and program-level assessment

The framework of collaboration used to develop and implement the GE are part of the new model of assessment. Previously, instructors developed their own, individual approaches to course-level assessment, which represented one of the most significant bottlenecks in course approval and course assessment because faculty did not have support in developing or administering their plan. Further, individual assessment outcomes could not easily be aggregated or compared to understand broader trends. Course assessment in the revised GE will bring together instructors teaching within a component of the GE to develop shared plans and metrics, with support of instructional designers to scaffold the process, as well as program staff to collate, digest, and share the results.[5] Explicit program goals make it possible for departmental units to see where their major programs overlap with or build from GE goals and allow co-curricular programs like the university’s Second Year Transformational Program (STEP) to see how their activities align with the goals of general education (see Appendix).

Final Thoughts

Re-imagining OSU’s GE has required community-wide collaboration and an intentional focus on the diversity of voices and perspectives represented within the OSU community. In Fall 2022, we will begin offering courses via the new GE program. We hope that this re-imagined GE, informed by inclusive design processes, an intentional focus on equity, and thoughtful integration of diverse data, equips OSU undergraduates with the skills and confidence to be global citizens for today’s world. We look forward to tracking the program’s progress and our students’ success.

Interested in learning more? For more information on OSU’s GE design and implementation, please contact Dr. Meg Daly at daly.66@osu.edu. For more details on the ATI Academic Equity CoP, please email Emily Schwartz at Emily.Schwartz@ithaka.org.

Appendix I: The Second Year Transformational Program (STEP)

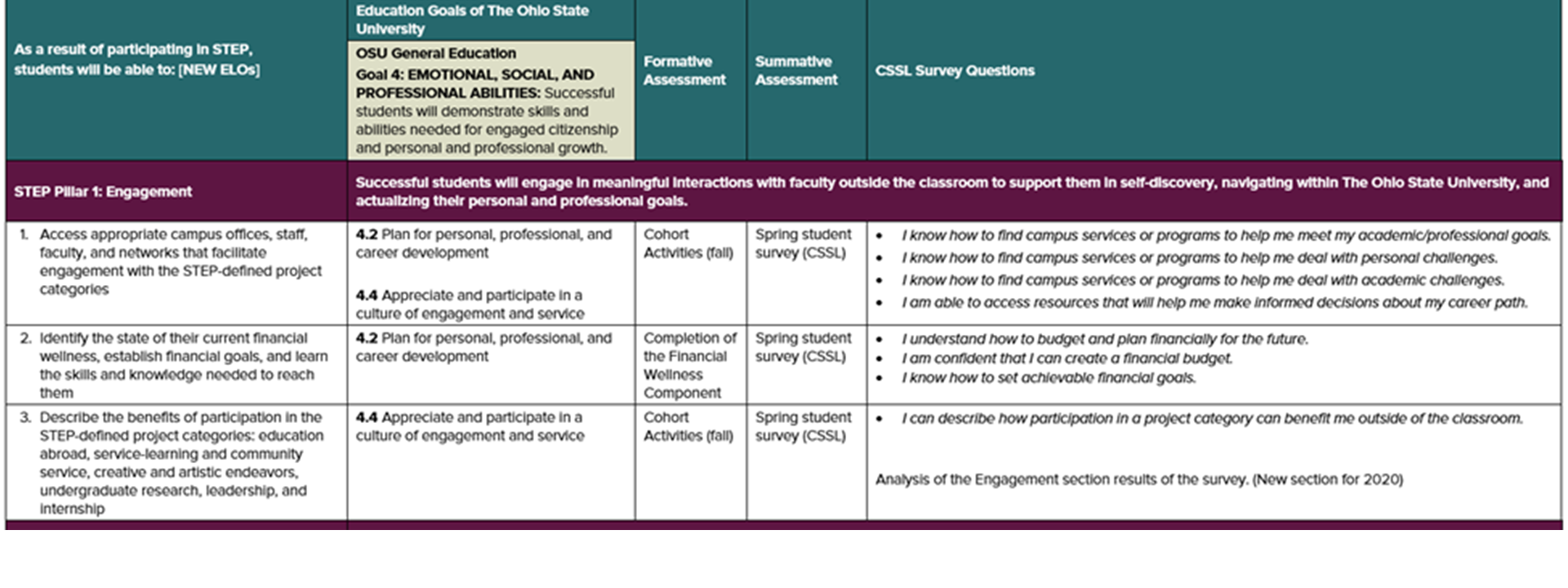

The Second Year Transformational Program (STEP) is a partnership between OSU’s Office of Academic Affairs and the Office of Student Life that focuses on both student engagement & student development. The activities within its pillar of “Engagement” align with the new GE’s goal for students to demonstrates the skills and abilities needed for engaged citizenship, personal, and professional growth. This overlap reinforces the centrality of the GE to the student experience at OSU.

This diagram shows the alignment of the STEP outcomes and GE goals, and identifies the ways in which STEP assays attainment of these goals. These data provide mid-progress checkpoints for understanding student’s progress towards the GE goals.

The American Talent Initiative (ATI) is a Bloomberg Philanthropies-supported collaboration between the Aspen Institute College Excellence Program, Ithaka S+R, and an alliance of top colleges and universities committed to expanding access and opportunity for students from low- and moderate-income backgrounds. ATI has one central goal: attract, enroll, and graduate 50,000 additional high-achieving students from low- and moderate-income backgrounds at the nation’s colleges and universities with the highest graduation rates by 2025. For more information about the American Talent Initiative, please contact Benjamin Fresquez at benjamin.fresquez@aspeninstitute.org.

Acknowledgements

The American Talent Initiative would like to thank

- The 37 members of the ATI academic equity community of practice, especially the staff who engage regularly with the community and lead initiatives on their respective campuses aimed at promoting greater equity in the academic experience.

- Randall Bass, Heidi Elmendorf, and Mark Joy, of Georgetown University, and Katie Brock and Ulili Emore, of The University of Texas at Austin, for spearheading activities for the community of practice and lending their time and expertise to advancing this critical work.

- Elizabeth Pisacreta for her guidance and support in the coordination of this case study.

- The staff of the Aspen Institute and Ithaka S+R who devote their time and energy to the American Talent Initiative, including Benjamin Fresquez, Mya Haynes, Martin Kurzweil, Tania LaViolet, Cindy Le, Gelsey Mehl, Yazmin Padilla, Adam Rabinowitz, and Josh Wyner.

- Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Aronson Family Foundation, and the Gray Foundation for supporting the work of ATI.

Members of the ATI Academic Equity Community of Practice

- Allegheny College

- Barnard College

- Baylor University

- Bowdoin College

- Claremont McKenna College

- Colgate University

- College of the Holy Cross

- Duke University

- Emory University

- George Mason University

- Georgetown University

- Hamilton College

- Hope College

- James Madison University

- Lebanon Valley College

- Middlebury College

- Muhlenberg College

- Pennsylvania State University-Main Campus

- Pomona College

- Princeton University

- Rutgers-New Brunswick

- Stanford University

- The Ohio State University

- The University of Texas at Austin

- University of California-Santa Cruz

- University of Dayton

- University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- University of Iowa

- University of Pennsylvania

- University of Pittsburgh

- University of Richmond

- University of Washington-Seattle Campus

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Vassar College

- Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

- Washington University in St. Louis

- Williams College

Endnotes

- “The GE Program,” The Ohio State University, https://oaa.osu.edu/ohio-state-ge-program. ↑

- See “Colleges and Campuses,” The Ohio State University, https://oaa.osu.edu/. ↑

- “The GE Program,” The Ohio State University, https://oaa.osu.edu/ohio-state-ge-program. ↑

- Ohio State University Foundation, Grantee, Grants Database, The Joyce Foundation, https://www.joycefdn.org/grants-database. ↑

- “General Education Program Structure,” The Ohio State University, https://oaa.osu.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/general-education-review/implementation/New-GE-Structure-Aug-2020.pdf. ↑