Consolidating the University of Wisconsin Colleges

The Reorganization of the University of Wisconsin System

Introduction

In 2017 to 2018, the University of Wisconsin (UW) System undertook a major consolidation, removing its two-year college campuses from a standalone sub-system known as the UW Colleges and merging them with nearby four-year UW institutions. The system-level motivation for doing so, in a state undergoing a demographic shift with an aging population, was ultimately budgetary, even if specific savings were not promised. The receiving universities followed several different models for their mergers, some of which appear to have been more successful than others. This case study of the consolidation at the University of Wisconsin System was conducted as part of a broader project examining equity issues, particularly pertaining to race and ethnicity, in the course of public university system consolidations.[1] While there is little evidence of equity serving as a major driver of this consolidation at UW, certainly not on racial lines, individual institutions made choices that, in some cases, may lead to improved outcomes for underrepresented populations.

Prior to 2018, the public higher education system in Wisconsin had a unique composition and structure. The University of Wisconsin (UW) System, itself the product of a 1974 consolidation,[2] included multiple institution types. Its 13 four-year universities included two major research universities and another 11 comprehensives, each overseen by a chancellor.

Additionally, the system included the UW Colleges, 13 two-year campuses, mostly located in small towns and with programs largely structured to enable transfer to bachelor’s degree granting institutions. Prior to the consolidation the Colleges had an aggregate enrollment of less than 10,000 full-time equivalency (FTE) students, a figure in steady decline. In the fall of 2016, total enrollment at the 13 UW College campuses declined steeply by 22.3 percent.[3]

Individual campuses within the Colleges faced punishing cumulative declines. One of the hardest hit, UW-Manitowoc, lost 52 percent of its enrollment between 2010 and 2017.[4]

Although each of the UW Colleges campuses had its own place-name identity, none were independent academic institutions. Rather, a single chancellor was responsible for the entire group, with administrative leadership and various shared services provided centrally. This chancellor’s portfolio also included several other “outreach” activities, including the statewide cooperative extension service, business and entrepreneurial services, and public broadcasting. This portfolio was an unusual combination. An entirely separate system, the Wisconsin State Technical Colleges, existed alongside UW, with many of its component institutions co-located with the UW Colleges.

In October 2017, Ray Cross, then president of the University of Wisconsin System, proposed a reorganization plan. The component parts of the UW Colleges and UW-Extension would be redistributed within the system. Most critically, the two-year campuses were to be merged into seven geographically proximate four-year universities, providing a more regional approach to the management of the system.[5] Cooperative extension and public broadcasting would be merged into UW Madison, the state flagship, their home prior to 1974.

The reorganization plan moved rapidly towards adoption and implementation. In November of 2017 the University of Wisconsin Board of Regents approved a resolution to go forward with restructuring UW Colleges and UW-Extension.[6] On January 16, 2018, the UW System submitted its application to restructure to the Higher Learning Commission (HLC),[7] which approved the application in June 2018.[8] This was the biggest reorganization in UW System history “since its inception by the legislature in 1971.”[9]

Table 1: UW Colleges Campus Restructuring Plan (made effective July 1, 2018). List of UW four-year institutions and the two-year institutions merged into them.

| UW Four-Year Institution | UW College Campuses |

|---|---|

| UW-Eau Claire | UW-Barron County |

| UW-Green Bay | UW-Manitowoc, UW-Marinette, UW-Sheboygan |

| UW-Milwaukee | UW-Washington County, UW-Waukesha |

| UW-Oshkosh | UW-Fond du Lac, UW-Fox Valley |

| UW-Platteville | UW-Baraboo/Sauk County, UW-Richland |

| UW-Stevens Point | UW-Marathon County, UW-Marshfield/Wood County |

| UW-Whitewater | UW-Rock County |

In conducting this case study, we interviewed current and former leaders across the University of Wisconsin system (see Table 2).

Table 2: List of Interview Participants

| Interviewee | Position and University of Wisconsin Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Rebecca Blank | Chancellor, UW Madison |

| Johannes Britz | Provost, UW Milwaukee |

| Ray Cross | Former President, UW System |

| Andy Leavitt | Chancellor, UW-Oshkosh |

| Cathy Sandeen | President, California State University East Bay (then Chancellor for the UW Colleges and Extension at the time of the consolidation) |

| Stephen Schmid | Special Assistant and former Interim Dean, UW-Milwaukee |

| Jim Schmidt | Chancellor, UW-Eau Claire |

| Dennis Shields | Chancellor, UW-Platteville |

To enable interviewees to speak freely, we have elected to attribute only a few quotations. Nevertheless, the narrative below is deeply enriched as a result of their generous contributions and candid reflections.

System-Level Strategy

Leaders were motivated by two principal factors as they pursued the consolidation. There was a series of budget cuts facing the UW System, driven in large part by the state legislature’s views about the system. And in looking for how to address these budget cuts, and avoid future cuts, there was a desire to address the economic and demographic changes that required substantially new approaches especially among the Colleges.

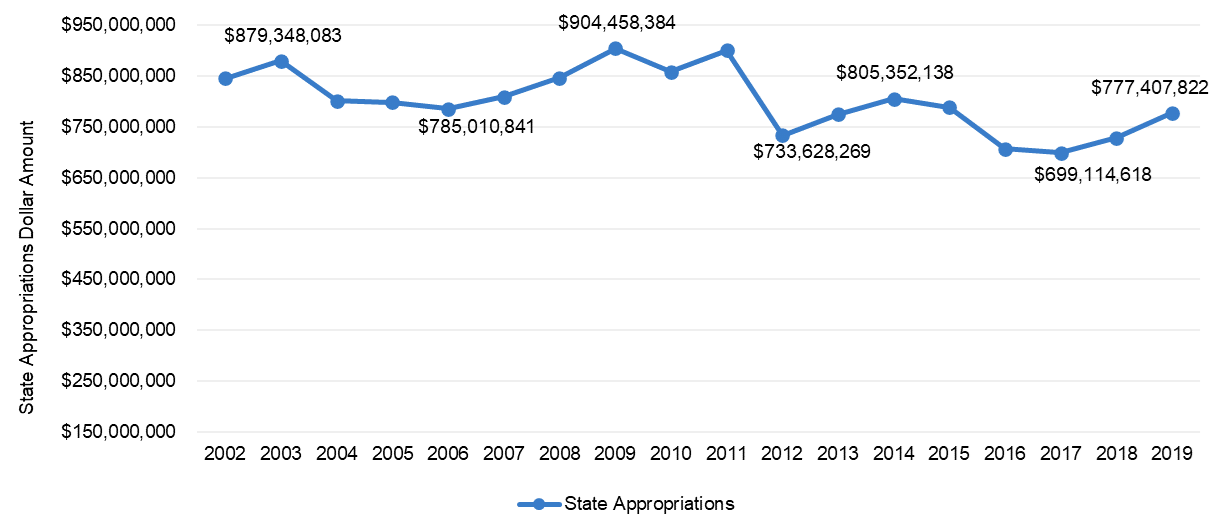

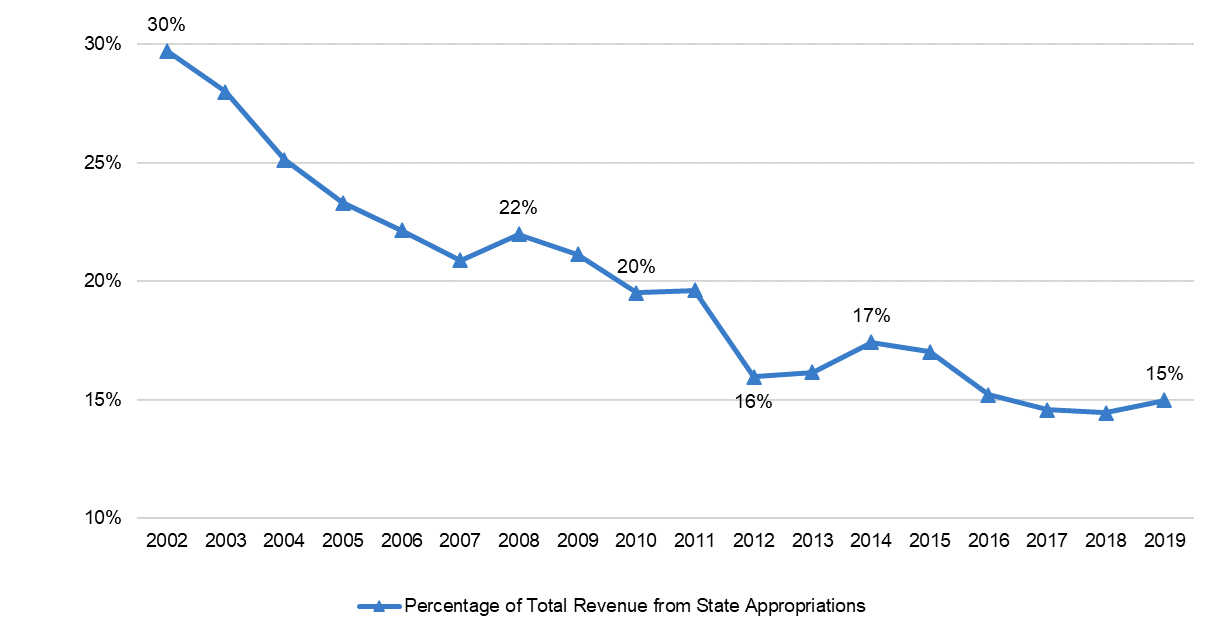

The basic background surrounding this merger contained enormous political controversies about the state university system, sometimes driven by claims that the system was too wealthy. Critics termed the substantial fund balances being maintained by the state university system “slush funds.”[10] Tuition rates were frozen starting in 2013[11] (and then extended again and again) to “make our universities affordable and accessible.”[12] When the state government proposed further reductions to the state university system funding, the governor suggested that faculty members should work harder to keep costs lower. [13] Figure 1 shows how state appropriations across the UW System remained largely flat over an extended period of time. In parallel, tuition, when uncapped, and other sources of revenue increased at greater rates.[14] As a result, the share of total revenue derived from state appropriations was approximately halved over a two-decade period (see Figure 2). Budget debates and constraints were a basic challenge for the university system and one that undoubtedly helped to motivate the consolidation.

Figure 1: State appropriations trends at UW-Eau Claire, UW-Green Bay, UW-La Crosse, UW-Madison, UW-Milwaukee, UW-Oshkosh, UW-Parkside, UW-Platteville, UW-Stevens Point, UW-Stout, UW-Superior, and UW-Whitewater combined from 2002 – 2019.[15]

Figure 2: Percentage of total revenue from state appropriations from UW-Eau Claire, UW-Green Bay, UW-La Crosse, UW-Madison, UW-Milwaukee, UW-Oshkosh, UW-Parkside, UW-Platteville, UW-Stevens Point, UW-Stout, UW-Superior, and UW-Whitewater combined from 2002 – 2019.

The more focused motivation driving the consolidation of the Colleges was demographic change. The state government was projecting a steadily aging population,[16] with substantial declines in the traditional college age population. The Colleges were located outside the major population centers of the state, in small towns where economic shifts were leading to declining enrollments among traditional student categories. At a statewide level, there was concern about projected population stagnation among working age adults (accompanied by steep growth in the retirement age population).[17] But the Colleges did not draw their students from across the state, rather they drew from local communities. And these local communities were in some cases faced with economic decline, as traditional industries closed, in some but not all cases replaced with newer forms of economic activity.

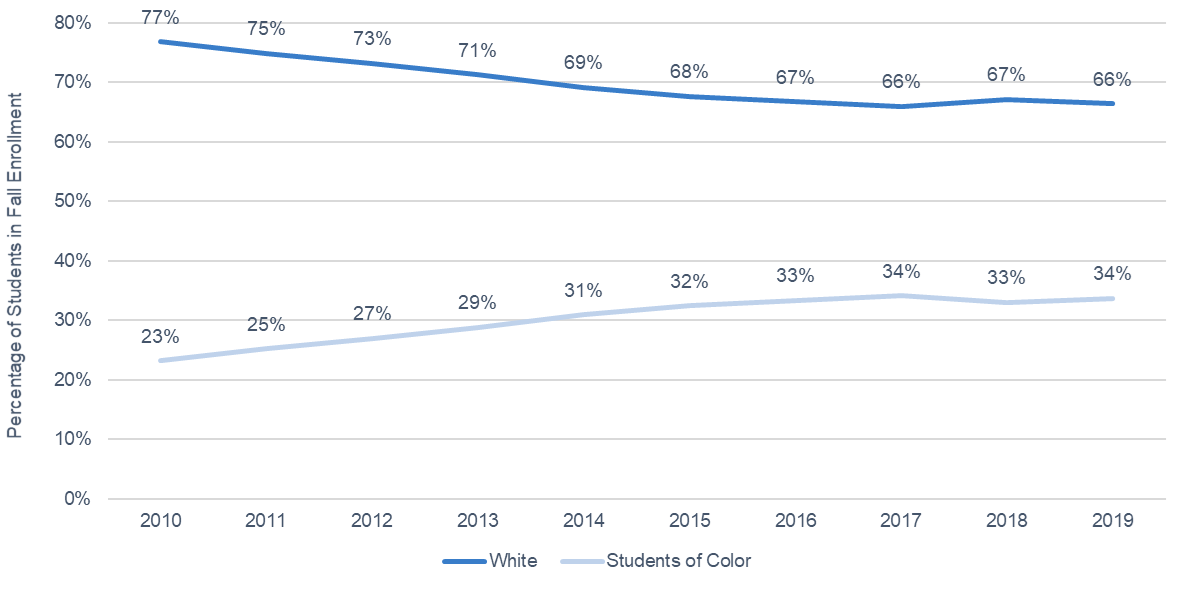

Wisconsin saw a significant increase in Latino population between 1990 and 2010, with clusters in Milwaukee initially but soon a substantial rural population. Many of these new residents were immigrants, and many had less than high school education. At the same time, in some counties, the children of immigrant families were keeping local schools fully enrolled, making up for declines in the white school-aged population.[18] For the UW-Milwaukee, this meant a substantial increase in Latino student enrollments, as illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3: Fall enrollments at UW-Milwaukee pre-and post-merger by race and ethnicity as shares of total fall enrollment at UW-Milwaukee. This table compares shares of the total fall enrollment racial and ethnic makeup from 2010 – 2019.*

Figure 3: Fall enrollments at UW-Milwaukee pre-and post-merger. White students vs. students of color[19] as shares of total fall enrollment at UW-Milwaukee. This figure compares shares of the total fall enrollment racial and ethnic makeup from 2010 – 2019.

Each of the campuses of the UW Colleges was very small, with most having only several hundred FTE enrollments. In many cases, these enrollments were in steep decline. Enrollment across all the UW Colleges had declined 32 percent from 2010 through 2017.[20] With 7,000 enrollments across the 13 institutions, the Colleges had in the aggregate become smaller than almost all of the individual four-year institutions, with the burden of maintaining separate programs across 13 campuses. Between state budget cuts and enrollment declines, the Colleges were unlikely to ever again be sustainable as standalone entities.

As Cathy Sandeen, then chancellor for UW Colleges and Extension, stated at the time, “The dramatic demographic declines in this state are undeniable and we have been working hard to ensure the future viability and sustainability of our small campuses.”[21] This included several elements to increase outreach and reduce costs. First, the Colleges were “regionalized,” with dean-level leadership for clusters of roughly three campuses each, and with centralization of certain services such as libraries and IT. Second, there was a plan to “right-size” some of the smaller college campuses and to develop customized academic programming based on the needs of each region. Third, there was a plan for a major marketing campaign, designed to position the Colleges as a gateway to the statewide system. And finally, there were plans to develop additional partnership programs with some of the four-year institutions, especially UW-Madison.

Notwithstanding these plans, the political and financial pressures facing the system were growing. It seemed time to do something more radical to address enrollment declines and financial sustainability.

One factor driving this enrollment decline was declining traditional-aged population in the two-year institutions’ communities. As a result, closing some of the under-enrolled UW College campuses might have been the simplest solution. Yet, some remembered local controversies in the early 1980s around efforts to do so,[22] and this approach was judged politically infeasible. Indeed, a primary motivation for moving ahead with the consolidation was to ensure that the UW System did leave these communities. This underlying logic was essentially political, recognizing the importance of maintaining and gaining allies in the state regions where the two-year campuses were located, which were largely rural and Republican.

System leadership considered other options, perhaps most significantly to merge the UW Colleges with the Wisconsin State Technical Colleges. This prospect seemed to have merit given that they were often co-located. But the Technical Colleges system jealously guarded its independence and spurned this early discussion. As Cross later reflected, “I would have preferred to merge them with the technical colleges but that wasn’t going to happen.”[23]

In the end, dismantling the Colleges as a standalone academic unit seemed to be the most feasible path forward. The plan was to assign responsibility for one or more struggling two-year campuses to each of several four-year universities that were comparatively stable and, in some cases, growing (See Table 1). As Cross said at the time, “We want to leverage the strength of our four-year institutions at a time when overall enrollments at UW Colleges are declining.”[24] Additionally, the Extension service—the other remaining element of the division that had reported to the same chancellor as the Colleges—was merged into Madison, the land-grant research institution. It is a fairly common model for the state land-grant institution to operate the extension service, the idea being to bring the fruits of the research enterprise to those in the state who can best apply them practically. In the eyes of some leaders, the previous model of connecting extension with the “access” campuses made these connections more difficult to develop.

System-Level Goals and Approach

The immediate motivation for this consolidation was at the intersection of demographic and budgetary concerns, but Cross was reluctant to speak about a budgetary goal. In 2017, Cross stated that “we must restructure these two organizations given the state’s demographic challenges, budgetary constraints.”[25] But he also remembers speaking widely about the reality that “You may never see a penny of savings.”[26] Cross would again and again try to frame the goal of the merger strategically. This was intentional. As he would later reflect, “Corporate mergers succeed for strategic reasons, not financial reasons. It was important to me that we defined success this way.”[27]

Looking back, Cross recalls several strategic goals for the consolidation.[28] These were ultimately about utilizing the new structure that would emerge to better leverage the educational capacity and readjust it to provide educational offerings that were better suited to the current and emerging needs of Wisconsin’s residents. As he said at the time, the merger would make it possible “to bring third- and fourth-year coursework to some of these [2-year college] campuses,”[29] providing them with new academic programs through which to serve communities in new ways. In this respect, the consolidation as it was pursued responded to the changing demographic composition and economic needs of the state. Of course, it also had the effect of delegating, if not burying, the demographic and budgetary challenges facing the two-year campuses in far larger and comparatively more stable universities.

One of Cross’s goals was to maintain and build upon some of the key assets of the two-year institutions. For example, Cross recalls that the two-year institutions had far greater student services, which he says have been vital for “underprepared” students. Maintaining these campuses and their student services was an important goal as an anchor for an array of educational programs that could be provided through them.

A second strategic goal was to enlarge the programmatic scope of the educational offerings on the two-year campuses to better match with changing needs for education in their communities. If successful, this would not only better serve these individual communities but also entice more students to enroll there thereby securing the critical mass necessary to their continued existence. As described in the section below on the individual UW mergers, one example of this is the addition of a variety of new programs, including some bachelor’s degree programs, at the post-merger two-year campuses.

While the goals may have been largely educational, there were a number of organizational and political outcomes, if not goals, that this approach enabled. Perhaps most importantly, having been president of SUNY’s Morrisville State College before coming to Wisconsin, Cross felt strongly that any consolidation needed to respect where there were strong senses of institutional identity. SUNY attempted to merge universities from the top down by appointing a single president to lead two universities, an effort that eventually failed.[30] Cross saw that by contrast the individual two-year college campuses in Wisconsin had identities individually that were never subsumed within the “UW Colleges” two-year system, so that reassigning them to the four-year universities would not materially impact their existing identities. There was no chancellor for any of the two-year campuses, although there was one for the entire UW Colleges whose position was eventually eliminated. Thus, the organizational politics of this move were comparatively straightforward and did not encounter substantive organized resistance.

Rural Wisconsin, and the small towns where the two-year campuses are found, historically tend to lean Republican, a factor that is essential to the political logic of the consolidation. One important element of the mergers was to give responsibility for each of the two-year campuses to a chancellor in the region, located at a nearby four-year university, rather than a chancellor in the Democratic-leaning state capital responsible for all of the two-year campuses. A senior individual “on the ground” would, Cross hoped, produce increased engagement with these rural and heavily Republican communities. He hoped to translate the strong local political support for each of the two-year campuses into support for the merged institutions, even those that were located in higher population areas with a more Democratic populace. The mergers could help additional communities see the economic and educational benefits for their own populations created by the UW System as a whole. If successful, then, the mergers could even have reduced some of the ideological split around the UW System.

The systems’ rhetoric at the time about goals and objectives was straightforward: “Our goal in joining UW Colleges with the UW’s four-year comprehensive and research institutions is to expand access to higher education, maintain affordability, and increase the opportunities available to students throughout Wisconsin and beyond.”[31] The primary objectives for the consolidation were to:[32]

- Expand access to higher education by offering more courses at the two-year campuses, including eventually offering upper-level courses

- Maintain affordability by continuing existing tuition levels post-integration for courses currently offered at the two-year institutions

- Identify and reduce barriers to transferring credits within the UW System

- Further standardize and regionalize administrative operations and services to more efficiently use resources

Pursuing the System Plan

The 2018 consolidation was implemented on several levels. The first was the work to initiate the consolidation and generate political support for it. This process was initiated in secrecy at the system level and almost immediately adopted. It came as a surprise to almost everyone who would subsequently be involved in the efforts to sort out how the merged organizations would operate in practice.

That said, the plan did not come out of nowhere. The question of how best to organize the Colleges had been present for some time, and proposals for changes surfaced from time to time. One version, including reassigning the two-year campuses to the responsibility of four-year institutions as well as putting Extension into UW Madison, was proposed by Eau Claire Chancellor James Schmidt during a previous cycle of state appropriation reductions in January 2015.[33] At the time, Schmidt recalls, the principal budgetary logic was to reduce the central administrative operation associated with running the Colleges, which was housed in Madison, and which was estimated at 30 percent of the total costs of running the UW Colleges.[34] However, at that time, Cross rejected the idea, perhaps not surprising given that he had previously served as chancellor of the UW Colleges![35]

In the ensuing two years, significant investments were made in the Colleges, including in marketing efforts. But with enrollments continuing to drop, just a little more than two years later, Cross advanced a remarkably similar proposal, with remarkable speed. Whatever the purpose might have been in the past, now it was not cost savings, but rather to shore up the Colleges in the face of demographic changes and enrollment declines.

Before the consolidation was announced publicly, the impending news was shared with the chancellors of the four-year institutions. This allowed for a brief period of negotiation and adjustment, as at least one two-year institution was assigned to a different university than in Cross’s initial proposal. Such discussions were at a very high level, very brief, and very confidential. It seems that Cross feared that any protracted discussion of the consolidation plan would lead to its failure. He recalls that he felt up against a wall to receive approval for the consolidation before further state appropriations cuts were made against the system. As a result, he acted in secrecy. He says today that he regrets having to do this, but he felt he knew the system and the issues well enough that urgency outweighed inclusiveness.

The plan was released publicly in October 2017.[36] It was presented to the UW Board of Regents, which debated it at a session in November 2017 and adopted it then by a decisive margin of 16-2.[37]

After the plan was adopted by the Regents, the priority at the system level was to move the plan forward expeditiously and without interruptions. For example, one substantial priority was to ensure that accreditation issues were addressed smoothly. They wanted to avoid the kind of challenge that Connecticut was already experiencing in merging together its 12 community colleges, including a years-long delay in merging accreditations.[38] The consolidation plan was aided by the fact that the 13 two-year campuses in Wisconsin were already branch campuses of the UW Colleges, so reassigning them to individual four-year institutions maintained their identity, from an accreditation perspective, as branches, simply now of a different parent university within the system. Leaders including Cross worked directly with the Higher Learning Commission, the regional accreditor for the Midwest and mountain states, to ensure that there would be no challenge to accreditation. Similar issues and resolutions arose with maintaining financial aid eligibility, which was tricky to navigate and a foremost priority.

The Individual UW Mergers

Then there was implementation at the institutional level, which was left in the hands of the “receiving” four-year institutions (see Table 1) and their chancellors and leadership teams. To explore how the individual mergers worked out, we spoke with key campus leaders from four of the “receiving” universities. All these individuals made clear, at least in retrospect, that they understood the fundamental need for some kind of consolidation. Many would have liked more time for decision-making, agreed that not all the individual mergers were fully completed even several years later, and in some cases felt that not all the mergers were likely to succeed in the end. But several of them had experience with consolidations at other public university systems, and no one appears to have questioned the fundamental need for a new approach with the two-year campuses.

One of the challenges faced by the individual universities was that different kinds of leadership were required for different elements of the mergers, several of which are discussed below. For example, developing the academic structure required a comparatively brief period of high-level leadership often in conjunction with faculty governance bodies. And, the kind of academic leadership that might be put into place for a relatively stable and sustainable institution was not necessarily going to work well when entrepreneurial drive is needed for extensive program realignment. Several of the universities experimented with several different leadership structures even within the first several years following the mergers.

In every case, one or two two-year campuses were assigned to a nearby university. But beyond this high-level similarity, each individual merger worked differently.

Academic Structure

Determining academic structure was one of the most significant issues faced by the consolidating institutions. Several of the universities merged the two-year campus’s academic organization into their own, integrating faculty members at a departmental level. As one chancellor explained, “But we wanted to have ONE faculty….There had previously been a disparity in expectations—publishing, grant-seeking, etc. Now they are all in the same department. It was important that we don’t have a caste system or two tiers.”[39] As a result, receiving universities grandfathered the tenure status of tenured faculty members from their two-year institutions, even though they likely would have experienced differing requirements. Efforts were also made to align compensation, workload, and future recruiting, tenure, and promotion requirements.

This approach was not taken at every institution. As a research university, Milwaukee faced perhaps the greatest academic alignment challenge in integrating UW-Washington County and UW-Waukesha, the two-year institutions. Its choice was to create a separate College of General Studies with which the faculty members from these two-year campuses could be affiliated, rather than merging the academic organization at a departmental level. This approach also allowed differentiated tuition rates and degree requirements. Finally, it enabled a decanal structure to oversee activities on the two-year campuses, providing not only academic leadership but also a clear line of oversight for student affairs issues as well. As we will see below, several other receiving institutions would come to recognize belatedly that there was a greater need for oversight of the two-year campuses that went well beyond academics.

Program Realignment

As discussed above, the consolidation was intended to produce a set of academic programs that would be better aligned with the needs of the regions where the two-year campuses are located. The work of program realignment requires a keen sense of market demand as well as an ability to match that demand with capacity. It does not have the same type of urgency as addressing tenure issues as part of a merger, to take one example, and it can be an ongoing process.

In retrospect, several universities have made real progress in building new degree programs at their two-year campuses that serve the economic needs of local regions. In some cases, these programs will begin to include a bachelor’s degree. One university has sought to bring a nursing degree program to a two-year campus that did not previously have it and is exploring further plans with business and technology programs. Another has sought ways to develop hospitality degree programs closer to a resort area, in a way that is seen to connect more deeply to the needs of a previously “invisible” Latino community. In some cases, preexisting programs have been wound down.

These kinds of programmatic realignments and partnerships might have been possible without the consolidation, and it is difficult to establish convincingly that they would not otherwise have taken place. In some cases, it appears from interviews that leaders from the four-year institutions were far more engaged in these opportunities, when responsible for their own institutions rather than when considering a partnership with another. For underrepresented populations, then, there may be cases where organizational changes result in improved opportunities in unexpected ways. In most cases, however, it remains too early to point to unalloyed successes.

The Two-Year Campuses

The two-year campuses were long funded through a hybrid model in which the county in which each is located paid for land and facilities, while the UW System was responsible for all operational expenses. UW maintained this model following the consolidation. This created some strange disconnects that the universities have sought to address in their mergers.

A specific example given by one chancellor involves the residence halls on one of the two-year campuses.: “Residence halls were like the wild west—disciplinary issues weren’t programmatically integrated into the student affairs structure because the buildings were not owned by the institution.” Consequently, even some of the universities that undertook a relatively complete academic merger have nevertheless established an assistant chancellor or associate vice chancellor for their two-year campuses. This provides a mechanism to address student affairs and other non-academic issues.

Because facilities remain the responsibility of the counties and not the UW System, the levels of investment vary widely, in some cases even between two campuses now affiliated with the same university. One chancellor noted that the physical appearance of one of the campuses compared unfavorably with the local high school next door. Encouraging enrollments in this type of dynamic is seen as challenging and yet outside the control of the university. As this chancellor explained, describing the need for local investment broadly, “We need more support and engagement from the county government—it’s clearly a step down from the adjoining high school to end up at the college. We need help locally to reach into the high schools, engage the Hispanic community, and develop joint high school/college enrollments. They want us to keep [the campus] in existence but aren’t really doing anything” to support it.

Outcomes and Lessons Learned

Merging the 13 Colleges into several four-year institutions provided a new model for operating these institutions, the result of which has been the development of a number of new academic programs that better serve the educational needs of underserved regions of the state. But, with several years having passed, the consolidation of 2017-2018 has not resulted in dramatic changes to the Colleges, either from an enrollment or a programming perspective. In 2021, more consolidation is in the air again.

The promise of establishing new academic programs at these branch campuses has seemed clear for some time. While it might have been possible for joint programs to be established without the mergers, the evidence shows that in this new configuration the four-year institutions’ chancellors and provosts were more likely to take leadership responsibility for program development at the two-year campuses. In this respect alone, the consolidation has had positive outcomes.

At the same time, it has proven to be impossible to establish the success, or for that matter the failure, of these mergers through any kind of rigorous external metrics. While enrollments have grown at many of the four-year institutions, the effect of the merger has been to eliminate the reporting of enrollments specific to the two-year campuses through the main national data source, IPEDS. Adding to this the enrollment shocks brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, it becomes virtually impossible to judge the success of the mergers from an enrollment perspective.

There are reasons to believe that less progress has been made than might have been hoped for. The pandemic of course was a huge disruption. Additionally, several of the mergers experienced challenges in terms of developing adequate administration and governance models for the campuses, issues that had to be resolved before major investments in academic programming could begin.

Today, leaders of several of the four-year institutions are optimistic about the prospects of the merged entities, but that is not so in every case. And it remains to be seen how a struggling merger can be addressed. But these consolidations may not be the last ones for the UW System.

Earlier in 2021, former governor and interim system president Tommy Thompson proposed merging the UW System with the Wisconsin Technical College System, the very proposal that Cross felt would be politically impossible, an indication that enrollment declines and financial troubles continue to face public education in the state.[40] If such a consolidation were to take place, there would be renewed questions about the right way to organize and deliver higher education in the smaller cities and towns of the state. Some envision the creation of what they see as a long-overdue community college system for the state. In that case, some if not all of the 13 campuses that comprised the UW Colleges could find themselves on yet another new pathway forward.

Endnotes

-

Martin Kurzweil, Melody Andrews, Catharine Bond Hill, Sosanya Jones, Jane Radecki, and Roger Schonfeld, “Public College and University Consolidations and the Implications for Equity: Lessons from Georgia, Texas, and Wisconsin,” Ithaka S+R, August 24, 2021, https://sr.ithaka.org/publications/public-college-and-university-consolidations-and-the-implications-for-equity.

- This merger combined the former University of Wisconsin and former Wisconsin State Universities to create what we now know as the University of Wisconsin System. ↑

- Karen Herzog, “Enrollment Fall at Several UW System Campuses This Fall as State’s Demographics Shift,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 6, 2017, https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/education/2017/10/06/challenging-demographics-senenrollment-falls-several-uw-system-campuses-fall-challenging-demographic/734596001/. ↑

- Karen Herzog, “Merger Would Keep UW System’s Two-Year Campuses Afloat Despite Steep Enrollment Losses,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 11, 2017, https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/education/2017/10/11/details-announced-proposed-merger-uw-system-two-and-four-year-campuses/753921001/. ↑

- “UW System to Restructure UW Colleges and UW-Extension to Expand Access to Higher Education,” University of Wisconsin System, October 11, 2017, https://www.wisconsin.edu/news/archive/uw-system-to-restructure-uw-colleges-and-uw-extension-to-expand-access-to-higher-education/. ↑

- “Approval of Restructuring of UW Colleges and UW-Extension,” University of Wisconsin System, November 7, 2017, https://www.wisconsin.edu/uw-restructure/download/Board-of-Regents-Restructuring-Proposal-Resolution-7.pdf. . ↑

- “Higher Learning Commission Application,” UW Colleges and UW-Extension Restructuring, January 16, 2018, https://www.wisconsin.edu/uw-restructure/higher-learning-commission-proposal/. ↑

- “US System Restructuring Is Given Seal of Approval by the Higher Learning Commission: Two-Year UW Campuses Join Four-Year Receiving Institutions as Branch Campuses,” University of Wisconsin System, June 29, 2018, https://www.wisconsin.edu/news/archive/uw-system-restructuring-is-given-seal-of-approval-by-the-higher-learning-commission/. ↑

- Kelly Meyerhofer, “UW System Merger Approved. Here’s When the Official Transfer Takes Place,” Wisconsin State Journal, June 30, 2018, sec. Topical, Top Story, https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/education/university/uw-system-merger-approved-heres-when-the-official-transfer-takes-place/article_aa4d164b-4983-5306-ab53-b1e766bd465c.html. ↑

- “UW Slush Fund More than Quadruples in Last Decade,” Maclver Institute, March 3, 2015, https://www.maciverinstitute.com/2015/03/uw-slush-fund-more-than-quadruples-in-last-decade/. ↑

- Nico Savidge, “Scott Walker Calls for Extending UW Tuition Freeze in Next State Budget,” La Crosse Tribune, October 21, 2016, https://lacrossetribune.com/news/state-and-regional/scott-walker-calls-for-extending-uw-tuition-freeze-in-next-state-budget/article_a0170857-ef41-5036-821b-ae57bde27e54.html?mode=nowapp. ↑

- Nico Savidge, “Scott Walker Calls for Extending UW Tuition Freeze in Next State Budget,” Wisconsin State Journal, August 2, 2016, Topical, https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/education/university/scott-walker-calls-for-extending-uw-tuition-freeze-in-next/article_5e4392c8-1155-56db-be4f-d92557960095.html. ↑

- Karen Herzog and Patrick Marley, “Scott Walker Budget Cut Sparks Sharp Debate on UW System,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, January 28, 2015, http://archive.jsonline.com/news/education/scott-walker-says-uw-faculty-should-teach-more-classes-do-more-work-b99434737z1-290087401.html. ↑

- “Annual Financial Reports,” University of Wisconsin System, 2021, https://www.wisconsin.edu/financial-administration/forms-and-publications/annual-financial-reports/. ↑

- It is important to mention here that all of this data was taken from IPEDS. Unfortunately, IPEDS does not report data on the UW Colleges and therefore the numbers in this figure may be slightly off from what is found in a UW annual financial report. This figure also excludes the UW System administration. These state appropriation numbers match what each UW institution reports for state appropriations under non-operating revenues and expenses in their annual campus financial statements. ↑

- “Demographics of Aging in Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Department of Health Services, 2019, https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/aging/demographics.htm. ↑

- In the late fall of 2017 information about UW restructuring was released. Here it became clear that the UW System was up against a challenge with state demographics, specifically around age. At the time of this information release, current age demographic trends indicated that the enrollment challenges were unlikely to see a significant improvement in the foreseeable future: “By 2040, nearly 95% of total population growth in Wisconsin will be age 65 and older, while those of working age 18-64 will increase a mere 0.4%.” “UW System to Restructure UW Colleges and UW-Extension to Expand Access to Higher Education,” University of Wisconsin System, October 11, 2017, https://www.wisconsin.edu/news/archive/uw-system-to-restructure-uw-colleges-and-uw-extension-to-expand-access-to-higher-education/. ↑

- See “Latino Demographics,” Latino Wisconsin Division of Extension, https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/latinowisconsin/latino-demographics/. ↑

-

Students of color for this figure refers to American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, two or more races, race/ethnicity unknown, and Nonresident alien. All of these races and ethnicities have been combined together in this figure to create “students of color.”

- Shamane Mills, “Colleges Struggle To Attract Students,” Wisconsin Public Radio, May 30, 2018, https://www.wpr.org/colleges-struggle-attract-students; “UW System to Restructure UW Colleges and UW-Extension to Expand Access to Higher Education,” University of Wisconsin System, October 11, 2017, https://www.wisconsin.edu/news/archive/uw-system-to-restructure-uw-colleges-and-uw-extension-to-expand-access-to-higher-education/. ↑

- “UW System to Restructure UW Colleges and UW-Extension to Expand Access to Higher Education,” University of Wisconsin System, October 11, 2017, https://www.wisconsin.edu/news/archive/uw-system-to-restructure-uw-colleges-and-uw-extension-to-expand-access-to-higher-education/. ↑

- See for example, Kelly Meyerhofer, “18 Months Into UW Merger, Small, Rural Campuses Still Struggling to Find Students,” Wisconsin State Journal, February 20, 2020, https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/education/university/18-months-into-uw-merger-small-rural-campuses-still-struggling-to-find-students/article_49d31545-7aee-5432-8e5f-a761c0ada14a.html. ↑

- Ray Cross, Interview by Roger Schonfeld, April 2, 2021. ↑

- “UW System to Restructure UW Colleges and UW-Extension to Expand Access to Higher Education,” University of Wisconsin System, October 11, 2017, https://www.wisconsin.edu/news/archive/uw-system-to-restructure-uw-colleges-and-uw-extension-to-expand-access-to-higher-education/. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ray Cross, Interview by Roger Schonfeld, April 2, 2021. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- “UW Regents Approve Merging System Campuses,” Wisconsin Public Radio, November 9, 2017, https://www.wpr.org/uw-regents-approve-merging-system-campuses.↑

- Patty Ritchie, “Suny Drops Plan to Merge Canton-Potsdam Presidents,” The New York State Senate, December 6, 2011, https://www.nysenate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/patty-ritchie/suny-drops-plan-merge-canton-potsdam-presidents. ↑

- “The New UW System,” UW Colleges and UW-Extension Restructuring, 2020, https://www.wisconsin.edu/uw-restructure/overview/. ↑

- “UW System Restructuring Is Given Seal of Approval by the Higher Learning Commission: Two-Year UW Campuses Join Four-Year Receiving Institutions as Branch Campuses,” University of Wisconsin System, June 29, 2018, https://www.wisconsin.edu/news/archive/uw-system-restructuring-is-given-seal-of-approval-by-the-higher-learning-commission/. ↑

- Dan Simmons, “UW President Ray Cross Feared Lawmakers Would Curtail Shared Governance, Tenure,” La Crosse Tribune, February 11, 2015, https://lacrossetribune.com/news/local/education/university/uw-president-ray-cross-feared-lawmakers-would-curtail-shared-governance-tenure/article_1a02ef62-91d0-56bd-8bdb-7aae3e371ca2.html. ↑

- Roger Schonfeld, Interview with Jim Schmidt, April 5, 2021. ↑

- Dan Simmons, “UW President Ray Cross Feared Lawmakers Would Curtail Shared Governance, Tenure,” La Crosse Tribune, February 11, 2015, https://lacrossetribune.com/news/local/education/university/uw-president-ray-cross-feared-lawmakers-would-curtail-shared-governance-tenure/article_1a02ef62-91d0-56bd-8bdb-7aae3e371ca2.html. ↑

- Karen Herzog, “Merger Would Keep UW System’s Two-Year Campuses Afloat Despite Steep Enrollment Losses,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 11, 2017, https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/education/2017/10/11/details-announced-proposed-merger-uw-system-two-and-four-year-campuses/753921001/. ↑

- “Regents Approve Concept to Restructure UW Colleges and UW-Extension,” University of Wisconsin System, November 9, 2017, https://www.wisconsin.edu/news/archive/regents-approve-concept-to-restructure-uw-colleges-and-uw-extension-news-summary/. ↑

- See for example, David Quigley, “NECHE Letter July 2019” (New England Commission of Higher Education (NECHE), July 12, 2019), https://www.ct.edu/files/pdfs/NECHE%20letter%20July%202019.pdf. ↑

- Roger Schonfeld, Interview with Andrew Leavitt, April 27, 2021. ↑

- Mia Lee, “UW System President Talks Consolidating UW System, Wisconsin Technical College Campuses,” The Badger Herald, March 3, 2021, https://badgerherald.com/news/2021/03/03/uw-system-president-talks-consolidating-uw-system-wisconsin-technical-college-campuses/. ↑