Unbarring Access

A Landscape Review of Postsecondary Education in Prison and Its Pedagogical Supports

Introduction

Postsecondary education in US prisons is a growing topic in both academic and political circles. While much of the discourse surrounding higher education more broadly focuses on students’ educational and employment outcomes, the conversation around postsecondary education in prisons often centers on the societal benefits of this programming, with a strong focus on reduced recidivism rates – the rates with which formerly incarcerated individuals engage in criminal acts that result in their re-arrest, re-conviction, or re-incarceration. With 1.5 million people incarcerated across state and federal prisons,[1] at an average annual cost of $31,000 per person,[2] reducing recidivism is an important metric. However, as is discussed in more detail in this paper, the field of higher education in prison deserves a stronger student-centered approach to research, policy, and practice that promotes a broader range of positive outcomes for incarcerated adults and their families, and ultimately the field of education and society at large.

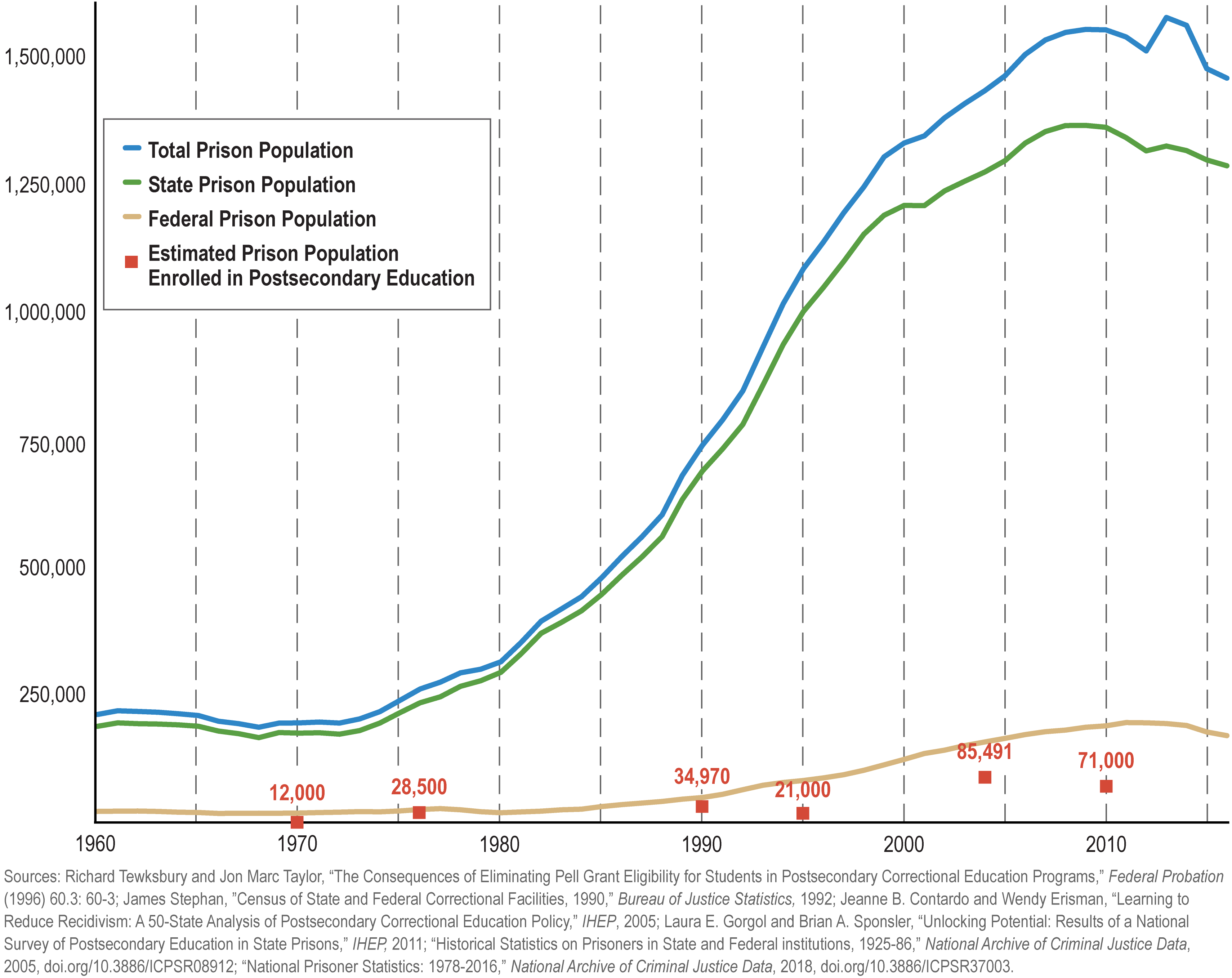

People in prison have disproportionately low levels of education, both upon entering and during their incarceration. In 2012 and 2014, only six percent of the incarcerated population held a postsecondary degree, compared with 37 percent of non-incarcerated persons.[3] Despite alarming increases in the number of adults held in US prisons over the last two decades, the very small shares of students who enroll in postsecondary education programs while in prison have decreased (see Figure 1). In fact, only nine percent of people in prison attain any postsecondary educational credential while incarcerated, mostly in the form of certificates.[4] By 2020, 65 percent of all jobs in the economy will require postsecondary education.[5] Yet 95 percent of all people in state facilities will eventually be released and need access to employment.[6] Given their low rates of postsecondary education, how will incarcerated adults gain the skills and tools they need for life outside? There are multiple barriers to postsecondary access and success for this underserved population, resting mainly in limited federal and public support for improving and expanding programs.[7]

Figure 1: US Prison Population and Postsecondary Education in Prison Enrollment

In 2019 The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation provided funding for ITHAKA, a not-for-profit organization with expertise at the intersection of higher education and information technologies, to conduct a landscape review of postsecondary education programs in prison and to identify pedagogical support needs for advancing student outcomes.[8] This multi-phase project reviews key policies, administrative structures, and student barriers to access and success to postsecondary education in prisons, and draws on a series of interviews with stakeholders, including leading experts, program directors, instructors, former students, and technology providers.

Ithaka S+R – which is part of ITHAKA – has expertise on policies and programs that broaden access to higher education, but this landscape review marks our entrance into the field of postsecondary education in prison.[9] As the first phase of this work, this review examines the lack of access to and information about postsecondary education in US prisons.[10] It surveys previous studies, paved by important research efforts led by the Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP), the RAND Corporation, and the Vera Institute of Justice. It adds to the extant literature by focusing its scope on credit-bearing postsecondary education in prison programs and by looking at the necessary pedagogical supports twenty-first-century programs need to equip students with a quality education. It argues that incarcerated students must be treated as a distinct population within higher education institutions, with unique needs that educators and other stakeholders should address in order to improve student outcomes and the field.

The report concludes by identifying priorities for advancing an agenda that ensures improved student outcomes more broadly and providing recommendations for how to best achieve this. This hinges on two major priorities: creating a coordinated research agenda and bolstering a community of practice for stakeholders. Both of these priorities will require significant additional support at the federal and state levels. In addition to these broader recommendations, we also share how the findings from this landscape review will be used to inform the next steps in the research ITHAKA is undertaking for this postsecondary education in prison project.

Background

This section provides a brief overview of the different perspectives stakeholders take when discussing postsecondary education in prison, including differing terms and vocabularies. It also provides a brief historical overview of the field, including access to higher education for US-incarcerated adults and available pedagogical supports.

Definitions and Philosophies

It is worth noting at the beginning of any research on people in prison the difference between several terms regarding US incarcerated adults. The US “correctional population” includes individuals housed in state or federal prisons, those retained in local jails, those on probation, and those on parole. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ most recent estimates, the total adult correctional population in 2016 was 6.6 million: 4.5 million consisted of adults under community supervision (i.e. on parole and probation) and 2.1 million were incarcerated. Of these incarcerated adults, 740,700 were detained in local jails while 1.5 million were held in prisons, the majority (1.3 million) in state facilities.[11] Incarcerated adults – people held in jails and prisons – are the focus of this report, though most information we have regarding students enrolled in postsecondary education programs focuses on the state and federal, rather than the local, level.

The term “prison education program,” often shorthanded as PEP, refers to several types of educational initiatives offered to incarcerated individuals. PEP can refer to juvenile secondary educational programming for students under age 18 and also includes adult secondary educational (ASE) programs that allow people in prison to earn their high school diploma or GED. PEPs also include adult basic education (ABE) classes that teach general arithmetic, reading comprehension, basic writing skills, and English as a second language; ABEs target students who read below the ninth-grade level. A large portion of adult PEP is comprised of vocation-focused training, which is referred to as career and technical education (CTE). CTEs, such as programs that instruct students on welding, horticulture, or automotive repair, sometimes grant incarcerated students industry certification or state licensure. [12]

Unlike ASE, ABE, and CTE, there is no common nomenclature of postsecondary education in prison. Approaches to these higher education offerings or college-in-prison programs often depend upon the grounding philosophy held by different players in field. These differing approaches not only dictate the language employed when discussing postsecondary education for the US incarcerated population, vocabularies that have in recent history become politicized,[13] but also dictate program goals, their desired outcomes, and the social science behind them.

Stakeholders with correctional backgrounds – such as state departments of corrections and the Federal Bureau of Prisons – use departmental language to describe higher education initiatives. For example, the US Office of Justice Programs refers to postsecondary education in prison as postsecondary correctional education (PSCE). It defines PSCE as “academic or vocational coursework taken beyond a high school diploma or equivalent that allows inmates to earn credit while they are incarcerated.”[14] Correctional departments typically focus on both the benefits of higher education on correctional facility operations as well as the societal benefits of postsecondary education in prison, and use metrics such as reduced recidivism as the primary goal for offering and funding such programming. This is the approach taken by the Corrections Education Association with the mission “to deliver quality education and help inmates achieve successful release and reintegration into society.”[15]

This approach is critiqued by many education providers, however; while they concede the societal benefits of educating incarcerated adults, they do not see this as a primary reason for providing such programming. For example, the Alliance for Higher Education in Prison formed to broaden corrections-centered approaches to postsecondary education in prison. It defines “meaningful, sustained, quality higher education in prison” as that which “is designed in the best interest of incarcerated students and in accordance with the highest standards and best practices of the field of postsecondary education.”[16] Those adhering to this philosophy champion postsecondary education in prison “without labels or stigmas,”[17] and eschew correctional terms such as “inmate” or “prisoner” when discussing incarcerated students.[18] These practitioners push back against the notion of “correctional education” as a concept and reduced recidivism as a primary goal, and move toward the philosophy that higher education in prison is just that – college at a different, albeit uniquely challenging, campus.

Early History (1834-1965)

Historically, early prison educational programs in the US were offered by religious organizations. For example, in 1834 Harvard Divinity College provided 30 tutors to work weekly with the incarcerated students at the Massachusetts State Prison. At the turn of the century, however, academic reformers began implementing structured college-level coursework inside. The University of California professors who started a program inside the San Quentin State Correctional Facility in 1914 were at the forefront of this movement. In their early history, credit-bearing postsecondary courses in specific were mostly student-funded correspondence courses, with the degree of financial support dependent upon the ebbs and flows of contemporary political climates. Wisconsin was the first state to offer such distance-learning programs in 1932.[19] The field for teaching in prison began to organize during this early history: The Friends of Prison Libraries and Correctional Education was founded under the aegis of the American Library Association in 1937 and published the first journal in the field, Correctional Education.[20] By 1955, California established televised postsecondary courses in prison and Illinois founded the first program offering live in-prison college instruction in 1962. In terms of pedagogical materials, most supplemental resources for education were donated to prison libraries, either from higher education institutions or private charitable sources.[21]

Pell Grant Era (1965-1994)

The golden age of prison education began when federal Pell Grants, originally called Basic Educational Opportunity Grants, became available for incarcerated students through Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965.[22] In this environment, higher education institutions began building specialized programs to enroll incarcerated Pell-eligible students.[23] This allowed for better access for lower-income students as they were no longer mainly dependent on their own funds to pay for postsecondary education in prison.[24] During this era, supplementary academic resources were provided almost exclusively by Pell-funded colleges, but there is a gap in the literature regarding how institutions’ academic libraries served students during this period. Targeted programs, such as Lehigh University’s Social Restoration Degree Program and Western Illinois University’s undergraduate degree in Corrections and Alternative Education were started to better prepare teachers instructing incarcerated students and to meet the demand for postsecondary education in prison instruction.[25]

Punitive Cutbacks and Program Decline (1994-2015)

The golden age of postsecondary education in prison ended in 1994 with the enactment of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which eliminated incarcerated students’ Pell grant eligibility. This legislative measure was based on policymakers’ push toward punitive rather than rehabilitative prison philosophies. In the first academic year after incarcerated students were excluded from Pell funding, student enrollment in postsecondary education in prison programs decreased 44 percent to just over 21,000 students.[26] This decline continued into the twenty-first century. Whereas it is estimated that approximately 14 percent of the total U.S. incarcerated population participated in college courses in 1991, only an estimated seven percent were enrolled by 2004.[27] With reductions to onsite postsecondary programs due to a lack of funding, motivated students turned to correspondence courses for attaining college. By this time, however, correspondence and distance learning initiatives had largely moved online, making these opportunities inaccessible to most incarcerated students who live without internet access due to security protocols.

Second Chance Pell (2016-2019)

In 2015, the US Department of Education announced the Second Chance Pell pilot program, an Experimental Sites Initiative designed “to test whether participation in high quality education programs increases after expanding access to financial aid for incarcerated individuals” and with the “goal of helping them get jobs and support their families when they are released.”[28] Initially, 67 colleges and universities were selected for the pilot, which was to run from 2016 to 2019, but recently the pilot has gained a fourth year at its current 64 test sites and is extended to 2020.[29] The program funds the approved higher education institutions directly, although these funds do not always cover the full cost of the program. Teaching formats under Second Chance Pell include onsite, in-person instruction, online, and hybrid programs. There is more discussion of how Second Chance Pell has altered postsecondary education in prison, including its unique eligibility requirements, in the following sections.

New Programs under Second Chance Pell

In 2016, through the Second Chance Pell test program, 25 higher education institutions were able to start offering prison programs for the first time.[30] Although data is not yet available on the effectiveness of these new programs, two examples highlight their potential for expanding access to students, as well as their diverse approaches to that end.

North Country Community College in New York was granted Pell eligibility for 129 students. The program offers in-person coursework across three associate degree programs: humanities and social science, entrepreneurship management, and individual studies. In 2018, the program graduated 32 students, some of whom were accepted by four-year institutions upon release.[31]

Similarly, Texas’s Wiley College, a historically black college, was granted eligibility for up to 300 students in three Louisiana state correctional institutions, with an estimated $5,815 funds per student. The college offers fully-online classes toward associate of arts, bachelor of arts, and bachelor of business administration degrees. Course materials are made available to enrolled students through tablets tied to a secured portal.[32]

Overview of Today’s Programs

One of the biggest challenges in understanding the current landscape of postsecondary education in prison is the lack of aggregate quantitative and qualitative studies on credit-bearing higher education programs. This affects what we know about how programs are organized, administered, and implemented, as well any impacts they have on students. This section provides an overview of the available research, while also discussing its limitations and our present inability to gather a holistic picture of American postsecondary education in prison programs.

Administration

Postsecondary education in prison program administration is difficult to analyze because of the variance in implementation across state and individual correctional facilities. There is no centralized administrative body at the federal level; the US Department of Education has an Office of Correctional Education (OCE), which is housed in the Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education Division of Adult Education and Literacy, yet the OCE acts as a coordinating rather than an administrative body.[33] This might be due in part to the fact that of the 1.5 million people incarcerated in US prisons, only nine percent are held in federal facilities.[34]

The OCE’s “Survey of State Correctional Education Systems,” last administered in 1992, shows the disparity in state-level administration of adult education programs. Most of the 43 state respondents reported that their adult educational programs fall under the purview of departments of corrections (43 percent), with other states administering their programs through correctional school districts (21 percent), decentralized educational systems (19 percent), departments of education (10 percent), or by other means (7 percent).[35] Whatever the governing agency, most states have a correctional education director, also referred to as a correctional education administrator, who oversees a large portfolio of prison programming, including postsecondary education, secondary education, GED preparation, special education instruction, adult learning classes, and ESL courses. Often this role oversees not only adult but juvenile education; 21 percent of OCE’s survey respondents noted that the administration of adult education was combined with that of juveniles in their states. To further complicate this landscape, some education administrators also run extra-educational programming such as religious services and substance abuse programs.

Examples of current state governance can elucidate this tangled administrative web. In California, for example, the Office of Correctional Education (OCE) sits under the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s Division of Rehabilitative Programs. California’s OCE oversees all in-person postsecondary education courses through a partnership with the California Community College Chancellor’s Office, but also runs the basic adult education, library services, and technical education programs within all state facilities.[36] Similarly, in Texas, the administration of “Academic and Vocational” postsecondary education in prison falls under the jurisdiction of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s coordinating entity, the Rehabilitation Programs Division (RPD). The RPD arranges contracts with local colleges and universities that enroll incarcerated students through independent admissions procedures and sets security-based eligibility requirements and classification clearances for admitted students. Again, this service is one of many that fall under the RPD’s purview, in addition to its Youthful Offender Program, Substance Abuse Treatment Program, and the Chaplaincy Department.[37] These two states, which have the largest prison populations and some of the longest running carceral higher education programs in the country, have layers of administrative burdens, overstretched resources, and limited budgets that arguably impede the administration and implementation of postsecondary education in prison.

Some states, however, are innovating their governance, recognizing that the successful implementation of credit-bearing postsecondary education in prison needs some degree of administrative desegregation from prison programming at large. For instance, since 2012, Tennessee’s postsecondary education in prison programming has run through the Tennessee Higher Education Initiative (THEI), a nonprofit that partners with the Tennessee Department of Correction and participating Tennessee colleges and universities. THEI directly funds such programming; its operational funding in 2018 was $384,215, 71 percent of which came from state appropriations.[38] In addition to having its own budget, THEI oversees postsecondary education in prison programming by coordinating admissions, eligibility, and academic curricula across all stakeholders. This includes managing articulation agreements between institutions and course transferability: “All credits, certificates and degrees earned behind bars are recognized by and transferable to any Tennessee Board of Regents (TBR) college or university, as well as SACS-COC accredited private and public colleges and universities outside of Tennessee.” Understanding that educational pathways (inside and out) are integral to program success, THEI also assists with formerly incarcerated students’ academic transition from the correctional facility to the college campus.[39]

Under the umbrella organization of a state’s department of corrections, prison wardens have a great amount of administrative control over all programs in their individual facilities. Wardens ensure that educational programs operating within the prison adhere to the policies and procedures set forth by the overarching department of corrections. Larger facilities have their own in-house educational directors, though many under-budgeted state systems assign that duty to a facility’s deputy warden.[40]

Of course, beyond corrections agencies and prison staff, the administration of postsecondary education in prison is also conducted by the directors of academic and vocational programs that offer coursework. These positions usually sit within the college or university offering a postsecondary education in prison program, a nonprofit program that partners with a higher education institution, or are an educational and non-profit combination. Directors of postsecondary education in prison programs perform a heavy amount of coordination with both state correctional education administrators and correctional facility leadership. In fact, for program managers who facilitate these programs, navigating administrative channels is a major challenge for the job.[41]

Thus, the successful administration of postsecondary education in prison requires collaboration among correctional agency administrators, prison staff, and program directors.[42] Though these relationships are critical, they can often be fraught given the involved parties’ differing mandates and philosophies toward carceral education.[43] Correctional agency administrators are typically tasked with ensuring compliance with state and federal policy, prison staff are primarily interested in ensuring safety and security within their facility, and program directors are usually concerned with offering the benefits of education that better students’ lives. We discuss some challenges posed by these diverse administrative perspectives on prison education in the “Barriers” section of this report.

Access and Enrollment

Because of a lack of systematic, standardized data collection, exact figures on national postsecondary education in prison enrollment are unknown. For example, the last Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities was issued in 2005, and though it counted “educational staff” and the percent of facilities offering “college courses,” it did not ask for the number of enrolled students in such programming.[44] A survey of 14,500 people in state and federal prison was conducted in 2004 by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which has shared the data through the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research, but includes very limited questions regarding education enrollment.[45] In 2006, the US Department of Education issued the “Correctional Education Data Guidebook” and a companion website to redress the critical dearth of data on incarcerated students. The goal of the two-pronged project was to enable state education administrators to gather, share, and analyze standardized data across US facilities.[46] However, the website was no longer live by 2015. Thus, without a standardized means for collecting information, the best estimates we have are from independent survey and research efforts, most of which were performed before the Second Chance Pell Era. These surveys tell us about facility and state participation in postsecondary education in prison programming rather than providing program- or student-level data. They also provide no information about the quality of programming being delivered. Taken in aggregate, while these surveys do not provide a complete picture, they nonetheless present the most thoroughly available information on postsecondary education in prison to date.

In 2010, the Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP) surveyed correctional education administrators from 43 states regarding their postsecondary education in prison programming for the 2009-10 academic year. They defined programming to be “any academic or vocational coursework an incarcerated person takes beyond the high school diploma or equivalent that can be used toward a certificate or an associate’s, bachelor’s, or graduate degree.” Importantly, this definition includes remedial, non-credit-bearing coursework that moves students toward either academic or applied degrees. Through this study, IHEP estimated that in 2010, across the 43 surveyed states, 35 to 42 percent of correctional facilities offered some form of higher education and that approximately 71,000 incarcerated students (or six percent of the incarcerated adult population in participating states) were enrolled in higher education programs, most of which were vocational or certificate programs. It is unknown how many of these students were actually earning postsecondary credit. The study did, however, uncover the low number of certificates and degrees conferred to this student population. In 2010, 9,900 incarcerated students earned a certificate, 2,200 earned an associate’s degree, and 400 earned a bachelor’s across 43 states. IHEP’s research highlights the important fact that there is disparity in enrollment across states: 13 of the 43 surveyed states educated 86 percent of the 71,000 incarcerated students in the 2009-10 academic year.[47]

During the 2012-13 academic year, the RAND Corporation conducted a more widely-scoped survey on prison education. Like IHEP, RAND’s study surveyed state correctional education directors, with 42 state officials responding. However, RAND’s survey focused on all educational programs offered to adults held in state prisons: adult basic education, secondary education, GED test preparation, career technical education, ESL classes, and special education in addition to postsecondary coursework. RAND’s survey supports IHEP’s findings that smaller states are less likely to offer postsecondary education in prison. It also found that while almost all of the 42 surveyed states offered some kind of prison education program to adult students, only 70 percent provided “adult postsecondary education/college courses” in at least one state correctional institution. Because it is unlikely that all correctional institutions within a single state offer such programs, it is difficult to estimate their prevalence.[48] Even more problematic is that at that time, less than half (43 percent) of the 42 participating states tracked the number of degrees their students earn and fewer (40 percent) captured data around college credits earned within their correctional institutions.[49] This insufficient student data capture seriously limits the ability to which we can understand and evaluate postsecondary education in prison.

In 2014, the Department of Education and the National Center for Education Statistics surveyed and assessed incarcerated adults for the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), a background questionnaire and direct cognitive skills assessment developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.[50] It showed that incarcerated adults had significantly lower scores in literacy and numeracy than non-incarcerated adults. Despite these scores, results indicated that the majority of adults surveyed (58 percent) did not complete further formal education after being incarcerated, and most who did stopped at earning a high school diploma or GED; this figure is of course greatly affected by the lack of postsecondary opportunities available inside. In fact, only 21 percent of surveyed adults were studying for a formal degree or certificate, while an additional 70 percent wanted to enroll in postsecondary education. Of those interested in enrolling, the vast majority wanted to enroll in certificate (29 percent) or degree (40 percent) programs. A quarter of these potential students, however, were on a waitlist.[51] This research underlines the desirability of credit-bearing postsecondary education in prison among the U.S. adult prison population, as well as the barriers to accessing high quality programs.

A number of vocal scholars and practitioners in this field have called for a change in the metrics used to assess postsecondary education in prison, arguing that we should not be collecting student enrollment and outcomes data from correctional authorities in the first place. Instead, they hold that students’ access and progress should be tracked similarly to traditional students: through the higher education institutions providing their education.[52] Recent figures have helped scope the landscape of community colleges and universities that are providing postsecondary education in prison. Findings published in late 2018 show that there are at least 202 higher education institutions providing credit-bearing coursework in 47 states.[53] Of these programs, 33 percent are funded through Second Chance Pell, including 12 percent that are new programs launched because of the re-instatement of Pell funding. In terms of the institutional sector, 55 percent of colleges offering postsecondary education in prison programming are public two-year institutions, 23 percent are private four-year institutions, 21 percent are public four-year institutions, and only one percent are for-profit institutions. Most of these programs are run by regionally accredited institutions, the highest tier of accreditation, indicating promise regarding the quality of the education provided to incarcerated students.[54]

In the absence of nationally representative longitudinal individual-level educational data for incarcerated persons, and standardized reporting on students’ outcomes by the postsecondary programs that serve them, national figures on key student outcomes, such as enrollment, retention, transfer, completion, debt, and employment, remain unknown. New figures coming out of Second Chance Pell show promise for program expansion and attainment rates, highlighting the need to bolster data collection structures and systems for more adequate research. The Vera Institute of Justice recently reported that a year after its implementation in fall 2016, Second Chance Pell’s enrollment grew 236 percent. By June 2018, the 64 colleges that participated in the pilot program offered more than 1,100 courses across 82 certificate, 69 associate, and 24 bachelor’s degree programs.[55]

Teaching Formats

Like many aspects of postsecondary education in prison, pedagogical structures within programs are understudied. What we do know is that due to security measures barring access to the internet and other distance-learning technologies, most programs are still delivered in-person, which requires significant facility resources: classroom space, security measures to clear faculty and teaching materials, and library space to store course materials. Scalable distance learning pedagogical formats are less common. For example, in 2010 all state correctional systems offered in-person instruction to higher education students in at least one facility, while about half offered correspondence courses, and around a quarter offered video or satellite.[56] However, third-party platforms are quickly entering this space and altering the landscape through, for example, tablet-based course delivery. More information about innovations in program delivery will be discussed in the “Information Delivery” section, as well as potential perils in the later section “Concerns for the Future of Postsecondary Education in Prison.”

Liberal Arts Programs

Though there are several kinds of postsecondary courses offered in prison, one typology of distinction is those that confer vocation-based certificates and degrees versus programs that confer liberal arts and sciences degrees. To extend access to the latter, the Bard Prison Initiative, operating since 2001, hosts the Consortium for the Liberal Arts in Prison. The Consortium engages 11 leading liberal arts institutions – including Yale, Wesleyan, and Washington University in St. Louis – to build a national college-in-prison network. It specifically emphasizes academic integrity, calling for courses “to be of the highest quality, ambition, and rigor” and to “[treat] the prison as only one site among many where we can and must push the frontiers of inclusive excellence.”[57]

Goucher College, a Consortium member, has leveraged this partnership to become the first and currently only college in Maryland to confer bachelor’s degrees to people in prison. Its 130 students work toward earning a Goucher four-year degree indistinguishable from that of its on-campus student population. A Second Chance Pell site, Goucher offers courses in political science, sociology, psychology, and English, among others, and because students have no internet access, Goucher supplies all texts and research materials.[58]

Private, elite universities are not the only institutions offering such programs. Milwaukee Area Technical College (MATC) considers its incarcerated students to be one of its eight “special population” student groups. MATC offers incarcerated students – which numbered more than 300 in the 2017-18 academic year – coursework toward an associates of arts and science degree to adults in the Wisconsin Department of Corrections through Moodle, a modified online course delivery platform. Students from neighboring colleges such as Marquette University use video conferencing to offer tutoring support to MATC’s incarcerated students, either one-on-one or through small group work.[59]

Program Impacts on Educational Outcomes

There are numerous challenges to gleaning an adequate understanding of the impact of credit-bearing postsecondary education in prison programs on participants’ educational outcomes. As described earlier, different players in this field hold diverging philosophies on the goals of higher education in prison and consequent desired outcomes. Stakeholder philosophies profoundly impact, and at times limit, both the science and available funding behind research on postsecondary education in prison. Presently, national figures on students’ educational outcomes remain unknown and rigorous research on program impacts is scarce, focusing almost exclusively on reductions in recidivism. Additional interrelated challenges that limit the scope and quality of research for understanding the impacts of postsecondary education in prison on students’ outcomes include the absence of adequate data on prison education programs and their students; research ethics restrictions on accessing and collecting data from people in prison, who are considered a protected group; structural issues that impact student access and retention, such as inter-prison transfer; and the absence of funding to support adequate program evaluation.

Selection bias is also a notable challenge that is difficult to overcome when adequate program evaluation efforts and related structures are not in place. Incarcerated students’ outcomes are often compared to those of the broader incarcerated population or to comparison groups that do not account for key differences that may influence eligibility, participation, and outcomes. For instance, incarcerated individuals with more advanced literacy skills, motivation levels, and available sources of program funding are more likely to self-select into educational programs[60] and succeed due to these protective factors than other individuals they are compared to. Additionally, program administration factors and eligibility criteria mean that participants are not representative of the entire potential postsecondary incarcerated student population. For instance, many corrections-focused programs enroll incarcerated adults as a reward for specific behaviors or, in the case of Second Chance Pell, enroll those on a five-year-or-less timeframe to release. These challenges leave the field with an incomplete understanding of whether and how expanding postsecondary education in prison can benefit different groups of students and society at large.

Research on the impacts of postsecondary education in prison on recidivism is not impervious to these challenges. In the most comprehensive meta-analysis to date, Bozick and colleagues identified only 11 primary studies of prison education program impacts on recidivism over a 37-year time period that they classified as highly rigorous.[61] Nonetheless, their final analyses, which include a broad group of studies with different levels of rigor and educational programming (including secondary education and non-credit bearing coursework), point to positive associations across the board. They estimate that students who participate in a prison education program are 28 to 32 percent less likely to recidivate when compared with their counterparts who did not participate in education programs.[62] In addition to its promising economic returns, reducing recidivism supports and maximizes the benefits reaped through postsecondary education at the individual level. Narrowly focusing on reducing recidivism as a key goal and outcome of postsecondary education programming in prison, however, is problematic. Recidivism measures do not capture essential and otherwise standard metrics of educational success, including adequate transfer and program re-entry, program completion, the earning of credentials with value in the labor market, and gainful employment. To stop at the absence of recidivism as a measure of success for formerly incarcerated students absolves stakeholders from ensuring appropriate and equitable learning, completion, and post-graduation outcomes for students. A strict focus on recidivism as an outcome can also alter criteria for recruitment and admission into programs, such that those responsible for admissions carefully select individuals “who possess a low risk for being a recidivist” into these programs.[63] This practice can further limit opportunity for incarcerated adults with the greatest barriers to access and those who might stand to benefit the most from postsecondary programing. In the absence of the right conditions for rigorous social science research in this area, it also further increases the risks of conflating correlation with causation and misleading the field.

To the extent that education programs promote students’ knowledge base, problem-solving strategies, and cognitive, moral, and social development – all hypothesized mechanisms by which education programs reduce recidivism,[64] postsecondary education in prison holds significant promise for bettering the educational outcomes of students more broadly. Participating in credit-bearing postsecondary education programs in specific may produce particularly beneficial educational, social, and employment outcomes out of prison compared with other types of educational programs. Combined with reduced recidivism, students theoretically have greater opportunities to further their education, pursue meaningful employment, and deploy their improved social and vocational skills as active participants in society. In reality, however, this potential for postsecondary education in prison cannot be met without ideological alignment among policymakers, researchers, and practitioners that promotes and organizes research and practice to support improved educational outcomes for students both pre- and post-release, across the postsecondary educational system at large.

Barriers to Postsecondary Education in Prison

Barriers to Access

Federal funds and policy have historically influenced students’ access to postsecondary education in prison. This is best evidenced by the significant drop (44 percent) in enrollment within a single year of eliminating Pell access for incarcerated adults.[65] Importantly, federal grants and policy initiatives each attach eligibility restrictions that limit access. Without a monetary incentive through federal, state, and local funds, higher education institutions may be less able, or willing, to provide courses to incarcerated students at sufficient scale, if at all.

Funding Sources

One of the biggest barriers to postsecondary education in prison is funding. In addition to federal funding cuts resultant from 1994’s Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, state spending has also declined. From 2009 to 2012, states reduced their spending on prison education programs by an average of six percent. Of these reductions, academically-oriented course offerings were reduced by 20 states in those three years, while vocational programming actually expanded by one percent.[66]

IHEP’s 2011 survey found that even before Second Chance Pell, the most common source of higher education funding for both low- (93 percent) and high-enrollment (100 percent) state prison systems was still federal grants.[67] The second most common source was family and individual finances (62 percent in high-enrollment states/77 percent in low-enrollment states).[68] IHEP also found that higher education programs in the 13 high-enrollment states were much more likely to receive funds from external sources than those in low-enrollment states, including from state appropriations (77 percent/23 percent), higher education institutions (38 percent/23 percent), philanthropic endeavors (38 percent/23 percent), and local sources (15 percent/7 percent). [69]

Before Second Chance Pell, the largest federal funding source for higher education in prison was the Grants to States for Workplace and Community Transition Training for Incarcerated Individuals, which last reported more than $17 million in annual appropriations before ending in 2010.[70] Second Chance Pell is currently the largest single federal funding source for postsecondary education in prison: the 2017-2018 academic year enrolled 11,000 students, and participating higher education institutions received a total of $22 million to fund students.[71] Another promising federal funding source of higher education in prison is the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act of 2006, which provides grants to states for career and technical education.[72] However, states cannot allocate more than one percent of their Perkins funding to prison education, inclusive of both secondary and postsecondary education initiatives.[73] According to 2018 Perkins grant figures, this puts the total national appropriations for all career and technical education in prison at just under $12 million.[74]

Eligibility Restrictions

There are several barriers to incarcerated students’ eligibility for postsecondary education in prison, which IHEP uncovered in its 2011 survey of state administrators. Low- and high-enrollment state prison systems differed on many of these elements, but both ranked the top prohibiting factor as time to release (85 percent for high-enrollment states, 87 percent for low-enrollment states).[75] For high-enrollment states, in-prison infractions are just as likely to restrict eligibility, whereas this type of barrier only affects 27 percent of low-enrollment states. Both enrollment categories noted that age, crime of conviction, standardized test scores, and length of incarceration were further restrictions to enrollment.[76]

Second Chance Pell experimental sites can only admit students who have completed high school (or received their GED), have met higher education institution admissions criteria, have completed a FAFSA, and are US citizens. Verifying Pell-eligibility for incarcerated individuals poses further obstacles. For instance, a recent evaluation by the Government Accountability Office revealed that compared with FAFSA applicants in the general population, potentially-eligible students at a number of pilot sites were especially likely not to have access to their Social Security Number, not to have registered for Selective Service, and to have federal student loans in default – all of which render the student ineligible.[77] Further, like all Title IV Aid recipients, incarcerated students who are convicted of a drug or sexual offense have limited eligibility. For example, if a student is convicted for the possession or sale of illegal drugs while receiving Second Chance Pell funding, Pell eligibility can be suspended. Eligibility suspension can be lifted through approved drug rehabilitation programs,[78] but this greatly affects incarcerated individuals who are still awaiting trial for a drug-related crime. Similarly, those convicted of a sexual offense and are subject to an involuntary civil commitment post-incarceration are ineligible to participate in Second Chance Pell.[79] Experimental sites also prioritize enrollment to students who are “likely to be released within five years,”[80] excluding a significant portion of the current US incarcerated population.

HEI Participation

Access to postsecondary education in prison within a given facility is limited to whatever programming is offered by higher education institutions. Research has shown that an estimated scant four percent of the 4,627 degree-granting, postsecondary Title IV institutions in the US offer credit-bearing coursework to incarcerated students.[81] The uncertain future of the Second Chance Pell Program could further reduce these numbers. As we discuss in more detail in the recommendations section of this report, greater participation from postsecondary institutions is contingent on state-level support and incentives. Institutions would also benefit from robust practice-sharing communities and a coordinated postsecondary education in prison research agenda that identifies program quality, effectiveness, and impacts.

Barriers to Effective Implementation

Our research uncovered the following barriers to effective implementation of higher education in prisons. These are not the only factors affecting the successful delivery of quality education for incarcerated individuals, but the most common themes cited throughout the literature on college education in prison.

Buy-in within Correctional Facilities

In terms of correctional agency administration, higher education programs in prison are sometimes viewed more as tools for social control than as essential reform programs that cut recidivism and otherwise benefit people in prison, a sentiment that has grown across correctional facility staff as prison populations continue to rise leaving facilities under-resourced. Prison education, in short, is often used a “carrot for good behavior,” an incentive earned by those who behave best.[82] Some correctional officers in particular do not see the benefits of postsecondary programming, and may even become resentful that incarcerated students are able to receive educational opportunities to which they never had access. Postsecondary prison programs that offer educational pathways to correctional officers and their families help alleviate this barrier to implementation and build buy-in among prison personnel.[83] The Prison Program at Saint Louis University, for instance, provides such programming, offering associate of arts degrees to both incarcerated students and prison staff. Since 2008, the program has served 4,500 students, who take credit-bearing classes as two separate cohorts.[84] Similarly, the long-running Boston University Prison Education Program has awarded 353 bachelor’s and 28 master’s degrees to students since its inception in 1972,[85] while the university also awards academic scholarships for Massachusetts Department of Correction employees.[86]

Correctional Facility Transfers

Because of the perceived lack of program import, and due to prison overcrowding, many incarcerated students enrolled in postsecondary education are transferred to other prisons during their sentence, often to facilities not equipped to allow them to continue their same learning pathways, or to prisons that lack postsecondary programs in general.[87] When students are transferred, they effectively withdraw from a course; these students are thus docked as being non-completers, potentially jeopardizing any future funding and enrollment eligibility at participating postsecondary institutions.[88] Postsecondary education in prison programs that build memoranda of understanding (MOUs) between the department of corrections and the higher education institution can help ensure that prison transfers will not impede a student’s progress to the degree or certificate.[89]

Credit Transfer and Articulation Agreements

Creating degree pathways is critical to long-term postsecondary education in prison success, especially since many incarcerated students lose credit earned inside post-release. Transferable credits are more cost effective, and in some cases, being enrolled in credit-bearing courses lowers the risk of facility transfer due to MOUs, which in turn greatly enables students’ program progression.[90] As previously argued, program directors should also be conscious of existing articulation agreements between colleges and universities so that courses are stackable to attain first certificates, then associate’s and later bachelor’s degrees. We have already seen how Tennessee’s THEI program has built this into their program administration. But other states have also organized transfer agreements for incarcerated students. In California, community colleges offering postsecondary education in prison offer students the opportunity to earn an associate’s degree of transfer (ADT), a stackable degree that transfers to any state public institution. This allows students to start their postsecondary education in prison and continue toward a bachelor’s degree outside of their correctional facility.[91] However, these streamlined articulation agreements are the exception, not the rule, within postsecondary education in prison.[92]

Limited and Poor Quality Educational Resources

One of the few qualitative studies available, which interviewed more than 80 incarcerated students, was published in 2013. The general dissatisfaction among students regarding their quality of instruction was a key finding. This includes students’ perceptions of the “inadequacy of instructors” and their “dissatisfaction with the quality of the educational material provided to them.”[93] Multiple reports have noted the high turnover in prison instructors, which is especially problematic given the unique training faculty must receive.[94] This is a major barrier to implementing postsecondary education in prison. The lack of adequate teaching materials and access to pedagogical support, a particular challenge within the security measures enforced upon the prison classroom, will be discussed in the following section.

Providing Academic Resources

The lack of publicly available information regarding how instructors are supported within postsecondary education programs in prison and how students access academic resources is a major impetus for this report. This section surveys extant studies in this area, arguing that information access and delivery is an important and overlooked element within current dialogues around program implementation. It discusses how prison libraries, postsecondary academic libraries, and information technology providers have traditionally provided educational support and examines the innovations some states and postsecondary education in prison programs are taking to better serve their incarcerated students.

Library Models and Academic Resources

Within correctional facilities, there are two primary library models that serve enrolled incarcerated students.[95] The first is the correctional facility’s library, which in theory, serves the entire prison population and is overseen by facility staff. These libraries have federal mandates to ensure legal resources are accessible to their incarcerated constituents, which often limits the availability of physical shelf space for other resources. Maryland’s Montgomery County Correctional Facility Library is an example of this model: its 15,000 books and other materials support recreational reading and legal research as well as educational programs.[96]

The second model is the library built by the postsecondary program, usually established as a response to the resource limitations of the prison library. This library is a separate space within the correctional facility that is typically restricted for use only by students who are enrolled in the sponsoring program. Materials that are permanently shelved within this library model are typically purchased through the postsecondary program budget or are donated.[97] The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Educational Justice Project (EJP) utilizes such a library model within the Danville Correctional Center. This two-room community library, which is exclusively maintained by EJP, holds the program’s book and CD collections, while also serving as a discussion space and tutoring center. EJP’s library is run by students who apply to be library workers, and their duties are to “organize the collections and maintain the atmosphere of the rooms so that they’re supportive of scholarly work.”[98]

Both models benefit from the partnership of an external academic library to facilitate resource delivery and navigate the research process. Library professionals have long identified this need. In the 1980s, Central Michigan University offered reference services to incarcerated students through free telephone calls; students working on course-assigned research and term papers were able to speak to campus reference librarians, who then mailed materials to students.[99] By the 1990s, a movement to extend the Standards for Distance Learning Library Services (adopted by the Association of College and Research Libraries) to incarcerated students began to form. These early initiatives included providing print copies of select library catalogs and indexes, performing interlibrary loan services, and building travelling collections of course reserves.[100] Today, several programs coordinate with academic librarians to provide students with reference services and resources through the use of research request forms.

As offline computer access has become more common across U.S. correctional facilities (see the following section), innovative librarians and academic resource providers have digitized resources for incarcerated students. In Iowa, Grinnell College’s campus library built an offline library catalog through VuFind, XAMPP, and flash drives.[101] Michigan’s Jackson College librarians have engaged in discussions with scholarly database provider Gale to develop offline access to article databases.[102] Similarly, JSTOR, a service of ITHAKA, developed an offline catalog originally for use by the Bard Prison Initiative and is exploring ways to scale up this program. However, for many postsecondary education in prison programs, both information delivery and affiliation with host institutions’ academic libraries are still rather limited. In these programs, the burden of material delivery falls upon individual instructors, who must follow strict screening procedures to ensure no contraband is brought into the correctional facility.

Access to Academic Research

Online resources for academic research accessed by students on the outside are almost completely unavailable to postsecondary prison programs. This includes digital databases for article searching, learning management systems that allow online discussion and sharing of materials, and online access to campus library catalogs and reference librarians. Even bringing analog research materials into the prison can meet security obstacles. Placing the burden on instructors to physically bring books and articles into correctional facilities is not an optimal delivery method, especially since all resources are subject to extensive security screening protocols. In fact, some states are beginning to ban all paper delivery to incarcerated individuals because of the potential to carry dissolvable narcotics on the page.

However, innovative programs are working to ensure that incarcerated students are able to experience the college research process even under these challenging circumstances. The University of Illinois’s Education Justice Project (EJP) not only works with the university’s academic library to provide materials in its community library at Danville Correctional, but also helps EJP students complete loan request slips for specific books and research topics from the UIUC collection. EJP community librarians fulfill these research requests with UIUC library materials, which arrive back in Danville for the student to use.[103]

Similarly, Jackson College’s program enables students to make research requests directly to Jackson reference librarians. These librarians review research request worksheets and provide instructional notes on their research processes to the requesting students. This includes their thought process for gathering materials and procedural steps taken to gain access to resources. One student’s direct thanks on the process: “Thank you greatly for the images and articles you provided for my Art 112 class…your work has rendered much better results that [sic] I expected.”[104]

Technology Access and Digital Literacy

RAND’s 2013 survey of 42 correctional education administrators found that computer use in carceral education programs is common. Arguably, computer access within correctional facilities has increased due to the GED’s 2014 move to computerized delivery, especially since 24 states require all incarcerated adults to participate in education programs if they have not yet earned a high school diploma or GED. As it stands, most states have at least one prison with a computer lab. In terms of hardware, 93 percent of surveyed states offer access to desktop computers, 40 percent offer access to laptops, and 24 percent offer access to tablets. Internet access is much less common. Though available to instructors within 73 percent of the surveyed states, only 38 percent offer simulated internet to students, and small numbers (14 percent) offer restricted live internet access.[105]

For those correctional institutions that do allow network access, most digital educational resources are offered through closed network access. Local area networks (LAN) are provided in 62 percent of U.S. state correctional systems; this kind of networking allows students to access articles and databases through a controlled intranet. Wide area networks (WAN) are offered by 26 percent of states; these networks are similar to LAN but can link multiple and even statewide correctional computer networks.[106]

The U.S. Department of Education is vocal in its support for computer- and network-based educational tools as a means for incarcerated students to develop their digital literacy skills.[107] These high-demand competencies are essential to today’s labor market and having them equips incarcerated students for both academic and workplace endeavors post-release. State correctional systems recognize this too: 57 percent offer Microsoft Office certification to their incarcerated population.[108] And programs such as TLM’s Code.7370 and Girl Develop It, which teach incarcerated students to code offline, are proving that a lack of internet access need not encumber students’ digital literacy.

Several states are innovating to provide incarcerated students in particular with the computer resources they need to succeed in their academic programs. In Washington, Peninsula College has built an isolated local server (ILS) at the Clallam Bay and Olympic corrections centers. This ILS, which moves internet content to correctional facilities’ LAN intranet, allows students to access a virtual web server. Through this server, instructors can share educational resources with students through Canvas, an open-source learning management system.[109] In New Mexico, the Department of Corrections has furnished nine facilities with WAN computer labs that connect to a centralized closed network server. Through this infrastructure, students can access educational course materials through Moodle’s course management system.[110]

Other states are turning to outside vendors to help solve network needs. Illinois has partnered with i-Pathways to deliver GED test preparation to 33 state correctional facilities using a customized, secure LAN network. Similarly, the city of Philadelphia engaged Jail Education Solutions’ Edovo platform for a pilot program testing educational tablets in its city jails. Incarcerated students rent the tablets for two dollars a day and can access postsecondary coursework over a restricted internet connection through a partnership with Saylor Academy,[111] a nonprofit organization that offers free and open online courses accredited by National College Credit Recommendation Service (a program of the Board of Regents of The University of the State of New York) and American Council on Education’s ACE CREDIT Registry and Transcript System.[112] However, there are issues with contracting third-party educational providers, as discussed in the following section.

Concerns for the Future of Postsecondary Education in Prison

Recent bipartisan support for postsecondary education in prison – such as the April 2019 introduction of the Restoring Education and Learning (REAL) Act, a bill that would restore Pell Grant eligibility for incarcerated students[113] – has created a fertile ground for program expansion. Prison education is increasingly gaining national attention,[114] and this is a watershed moment for policy, practice, and innovation. This section discusses some of the major opportunities and concerns for the future of postsecondary education in prison, with an eye toward access, scalability, and quality.

Second Chance Pell and Program Evaluation

The Experimental Sites Initiative Second Chance Pell ends has been extended to 2020. The program has had important impacts regarding postsecondary access for people in prison through partnerships with state and federal prisons across 64 colleges in 27 states.[115] For the 2018-2019 academic year, for example, more than 10,000 incarcerated students have been awarded Pell grants to fund their postsecondary education through Second Chance Pell.[116] Postsecondary credentials earned thus far during the experiment include 701 certificates, 230 associate’s degrees, and 23 bachelor’s degrees.[117] Second Chance Pell also launched 25 new postsecondary in prison programs – 40 percent of the sites operating under the experiment – which shows promise that more colleges will begin to offer such programming if federal funding were to become permanently available. The upcoming expansion of the Second Chance Pell program to include new sites may offer such an opportunity.[118]

However, simply extending and expanding Second Chance Pell as it is currently structured creates several issues worth noting. First, there was no formal evaluation built in to the experiment at large. The Department of Education notes the following: “School-reported student-level data, responses to school surveys, and existing [Federal Student Aid] data sources will be used to produce a report of the first two years of the experiment.”[119] Such a report has yet to be produced, but the premise of using disparate data self-reported through prison sites is a flawed methodology for program evaluation. Such reporting tells us little to nothing about how programs were implemented, their teaching formats, curricula designs, and pedagogical supports (among other important program documentation). Without being able to compare disparate implementation strategies across the 64 sites and common metrics for program evaluation – such as student retention, engagement, transfer, and completion – we have no collected information to inform policymakers and program staff on successful strategies that provide the types of quality education that best promote student outcomes and lead to employability post release.

There is also concern over how eligibility under Second Chance Pell is currently administered. As previously discussed, participants are selected from a small pool of academically eligible adults and selection directly privileges eligibility for incarcerated people likely to be released within five years. The goal of Second Chance Pell is “to supplement not supplant existing investments in postsecondary prison-based education programs,”[120] yet some fear that higher education institutions might chase this new line to governmental money and build low quality income-generating postsecondary education in prison programs. This is an especially timely and topical concern given the financial pressures both private and public colleges are increasingly facing.[121]

Technological Interventions and Profit-making Initiatives

Given the large onsite resource needs postsecondary education in prison requires, some programs are adapting scalable technology-based curricula that use tools and hardware supplied by for-profit technology vendors, controversially eliminating in-person instruction. Ashland University, for example, is one of the largest Second Chance Pell experimental sites, having been allocated funds to educate more than 1,000 Pell eligible students. It uses tablet-based models of postsecondary course delivery to more than 30 prisons in three different states via JPay’s Lantern, an Android tablet loaded with proprietary and secure learning management software.[122] Though such endeavors promise a growth in scalable access to incarcerated people, such technology has several issues to be addressed before broader adoption.

Importantly, companies like JPay and Global Tel Link have been giving free tablets to the incarcerated since 2016, independently of postsecondary education programs. JPay recently distributed 52,000 free tablets to New York prisons, and expects not only to make that money back, but create $9 million in profits through this endeavor by 2022. This is done by using the tablets to charge high service rates for users’ access to video chats, music, and money transfers, profiting off the incarcerated who average $0.92 per hour for their labor.[123] It should be noted that because of this business model, JPay is currently facing a class action lawsuit for allegedly exploiting incarcerated people to pay exorbitant fees for accessing their own money in prison, which for many states is the only way family members can send funds to people inside.[124] Incarcerated people do not have a choice of service providers; contracts with companies such as JPay and Global Tel Link are made through states’ department of corrections. Postsecondary education in prison must evaluate the risk of student exploitation before committing to a technology-centric model of educational delivery, and select vendors accordingly. It is also worth asking if providing digital materials for guided self-learning meets the traditional values and quality measures of higher education. Certainly using technology to support and supplement postsecondary coursework will train students in the digital literacy and research skills most college students gain during their education; but educational engagement and opportunities for developing certain important soft skills may be lacking when the physical classroom is entirely removed and learning takes place in isolation.

Technological vendors are not the only entities primed to capitalize on incarcerated students through postsecondary education in prison. Proprietary universities, private prisons, and even states themselves could potentially profit off of incarcerated people in the name of postsecondary education.[125] In fact, the claim that for-profit colleges were rampantly and fraudulently collecting Pell Grant funds to increase their bottom line and in turn providing little to no education for incarcerated students was used by legislators to support the 1994 bill that ended Pell eligibility for people in prison at that time.[126] Such Pell fraud has recently been exposed across swaths of the for-profit sector over the last five years, uncovering exploitation of non-incarcerated students who have more choice in higher education institutions than those in prison.[127] Guidelines that restrict such exploitation of people in prison, who have little to no choice of the postsecondary programs offered within their correctional facility, must be put in place to ensure this does not occur in future permutations of federal funding for postsecondary education in prison.

Similarly, private prisons, often publicly-traded companies with the incentive to maximize prisoner count per facility while minimizing operational costs, have the potential to reduce the quality of services offered in order to boost profits and increase shareholder value.[128] This includes the administration of educational programming, which comes from correctional facility budgets under contract with federal and state governments. As one oft-cited study concludes, “A for-profit prison operator thus has almost no contractual incentive to provide rehabilitation opportunities or educational or vocational training that might benefit inmates after release, except insofar as these services act to decrease the current cost of confinement.”[129] Recent studies have found that recidivism risk is significantly greater among individuals released from for-profit facilities vs. county- and state-operated facilities, and point to poor rehabilitative programming opportunities as one of the key reasons.[130] Federal and state contracts with private prisons, if the practice is to continue, should provide penalties for low-quality programming, including the management of postsecondary education.

While it is clear that postsecondary education in prison requires more resources, from the reinstatement of Pell funding for incarcerated students to the assignment of educational support through private contracts, these resources should also be subject to thoughtful and strategic constraints.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Incarcerated students constitute a distinct population within the broader higher education system. As argued by the Alliance for Higher Education in Prison, increased access to higher education includes providing opportunities for the large US incarcerated population.[131] These students – much like students who are single parents or students with limited English proficiency – have specific pedagogical challenges that should be addressed by the higher education institutions serving them.[132] While the bulk of scholarship on postsecondary education in prison to date has focused on correctional aims, and reduced recidivism is a powerful metric that strengthens the argument for social betterment through postsecondary education, there is potential to improve pedagogical contexts by adopting a more student-centered approach to research, practice, and policy. Ultimately, investing in the educational outcomes of incarcerated individuals serves the public good by providing people with the tools to reach their full potential, give back to their communities, and contribute to the democratic mission of our society, which in turn reduces crime and controls the cost of corrections.

Creating a Student Outcomes-Oriented Research Agenda

A major barrier to understanding how to maximize student outcomes is the lack of aggregate quantitative and qualitative research on postsecondary education in prison programming and outcomes. Two major studies are currently underway to collect much-needed data.[133] It is also crucial that ongoing, coordinated efforts be developed to collect evidence on pedagogical support needs and outcomes.

Four elements are essential for successfully developing coordinated postsecondary education in prison research:

- Standardize educational data collection across U.S. correctional facilities. More than a decade ago, the US Department of Education published its “Correctional Education Data Guidebook,” which prescribed standards for educational data collection upon individuals’ entry into the correctional facility. The initiative was not adopted, but data standardization efforts are necessary to form a baseline for future studies on incarcerated students and their outcomes. Such metrics, ideally, would be updated if and when incarcerated students enter and exit educational programming, including postsecondary education in prison.

- Identify the effects of postsecondary education in prison on student outcomes. Most outcomes-based research on postsecondary education in prison – and carceral education at large – analyzes blanket measurements of student outcomes and of recidivism rates in particular. Research is needed to uncover the specific impacts individual programs have on learners’ outcomes more broadly, such as degree attainment, student persistence, student engagement, sense of belonging, deep learning, time-to-completion, and labor market outcomes. Similar to research on postsecondary program impacts outside the prison context, this includes inquiries into credit accrual and transferability across institutions. This work should be driven by theoretical frameworks that generate targeted research questions and hypotheses regarding the mechanisms linking specific programmatic features to student outcomes and conducted according to the federal regulations that govern research on vulnerable populations.

- Examine the features of postsecondary education in prison and their effectiveness. Studies must also evaluate the pedagogical resources employed by these programs. How effective are different classroom models? How relevant is the vast body of pedagogical literature aimed at traditional students to teaching and learning within the prison population? What extracurricular and/or social layers are combined with coursework? How is information delivered to students to meet their research and discovery needs? What are the administrative qualities that undergird these programs? What role do incarcerated individuals have in the development/leadership of postsecondary education in prison programs? Eventually, it may be possible to evaluate the effectiveness of specific types of programs by these and other features. Such comparative analyses are critical for calibrating the next era of postsecondary education in prison programming, and will inform policymakers, practitioners, and curriculum designers.

- Study the effectiveness of Second Chance Pell. Second Chance Pell has provided researchers with a dataset of 11,000 students and 64 postsecondary prison programs. Selecting a diverse sample of programs and students to conduct longitudinal impact studies may uncover the effect of federal funding on life outcomes for participants, such as employability, health benefits, and social engagement.[134] By conducting a series of qualitative and small-scale evaluations of specific programs and initiatives of interest, it would be possible to trace the long-term benefits of select pilot programs and better understand how to support and develop postsecondary programming for incarcerated students moving forward.[135]

Developing Practices to Maximize Student Outcomes

In addition to standardizing data collection, it is important that existing collaborative networks of higher education institutions, correctional facility staff, program instructors, and department of corrections officers continue to meet regularly to improve postsecondary education in prison programming, data collection, and advocacy. For example, The Alliance for Higher Education in Prison – “a national network dedicated to the expansion of quality higher education in prison, empowering students in prison and after release, and shaping public discussion about education and incarceration”[136] – runs an active listserv amongst stakeholders and organizes the leading conference in the field.

Moreover, there is great potential to leverage such networks to foster communities of practice focused on student outcomes including:

- Increasing institutional participation through state-level advocacy. Presently only four percent of American higher education institutions are estimated to provide credit-bearing prison education, with the majority concentrated in 13 states. In order to increase access, more colleges and universities should begin offering programming. Widespread program availability also improves postsecondary retention among incarcerated students who are transferred across facilities. Similarly, many programs in existence are currently serving small populations of incarcerated students and must grow to provide better support. Changes in state legislation, spurred by advocacy networks, can offer significant incentives for higher education institutions to develop and strengthen postsecondary education in prison programs. For example, a 2014 California law that allowed community colleges to include face-to-face prison courses as a part of their standard budgets led to an explosion in postsecondary in-prison programs, and in student enrollment in transferable degree-granting courses.[137] Serving the incarcerated population provides unique benefits to state colleges and universities: As more state systems are under financial stress due to declining higher education appropriations,[138] the incarcerated student population serves as a viable source of increased enrollment-based funding.