Of Meetings and Members

The Interconnected Future of Conferences and Scholarly Societies

Introduction

Conferences have been an essential part of the modern scholarly communications landscape since academic communities began organizing themselves into disciplinary associations in the late nineteenth century. With some estimates indicating that there are more than 4.5 million presentations delivered at academic, scientific, and professional conferences annually, conferences are numerically at least, the “major medium of scientific communication.”[1] Many of these presentations are made at the annual meetings organized by scholarly societies.

Annual meetings are often the largest and most expensive public facing activities that societies engage in.[2] Meeting locations are often locked in several years in advance (mid to large size societies often sign hotel contracts five to seven years in advance), while society staff begin planning for the next meeting in earnest as soon as the current one ends. Some societies treat annual meetings as profit-centers that will subsidize operating costs, but even if budgeted to break even, the revenue generated by annual meetings is critical to the long-term financial health of the organization.[3]

The annual meeting offers unparalleled opportunities for societies to influence the direction of research agendas in their field, highlight professional issues, and facilitate networking within their membership and the broader disciplinary community. Annual meetings often serve important governance functions through business, caucus, and board meetings. They also provide opportunities to gather feedback and ideas from members, as well as to identify and recruit new committee and board members. Perhaps most importantly, annual meetings are gathering places for the disciplinary and membership communities that societies serve, places where scholars gather in large numbers and across subfields for intellectual and interpersonal exchange.

Annual meetings are gathering places for the disciplinary and membership communities that societies serve.

Despite their importance and ubiquity, annual meetings faced significant criticism even before the COVID-19 pandemic, much of it focused on exposing the limitations of in-person conferences. Criticism of in-person conferences can be loosely grouped into four categories: cost, access, culture, and climate. Graduate students and early career scholars, contingent faculty, and faculty from under-resourced institutions noted that the high cost of attendance prohibited their attendance and exacerbated inequities within higher education.[4] Minoritized scholars described facing micro-aggressions, snubs, and harassment that made the boundaries and fault lines within scholarly communities all too clear while scholars with disabilities often felt excluded entirely from participating.[5] Environmentally conscious scholars have made urgent appeals for reducing the climate footprints of in-person meetings.[6] All these criticisms mirrored frustrations voiced on social media and elsewhere by scholars who believed their field’s scholarly society was stuck in its ways, insular, and inattentive to the concerns of early career scholars and with stagnant or declining society membership.[7] For the most part, these criticisms resulted in minimal changes to the conference status quo, and the overwhelming majority of conferences remained strictly in-person events.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic forced societies to experiment at scale with virtual conferences. The virtual meetings of 2020-22 were much more successful than pre-pandemic conventional wisdom would have believed possible—a testament to the efforts and creativity of society staff. Indeed, in 2020 there was palpable excitement about “redefining,” “overhauling,” and “rethinking” the academic conference as virtual or hybrid events.[8] Though their limitations—especially around social and networking aspects of conferences—quickly became apparent, virtual formats greatly increased access to cutting edge research by attracting participants and audiences that were considerably more diverse than the attendees of in-person annual meetings.

As the pandemic recedes into memory, societies find themselves at a crossroads. For several years, the decision to hold hybrid or virtual meetings was dictated by outside forces: it has now become a question of societies’ priorities, mission, and values. 2023 has seen many societies (including members of our cohort) returning to primarily in-person conferences. It is too early to tell whether the virtual meetings of 2020-22 were anomalies, but a casual observer might reasonably describe the “new normal” as nearly identical to the old one. A closer view suggests a more nuanced picture. Virtual-only meetings remain visible parts of the conference landscape, annual meetings now routinely include virtual and/or hybrid programming, and many societies are now offering regular virtual content that might previously have been in-person events throughout the year. These changes do not amount to a radical transformation of the genre, but they do indicate that societies—never the most nimble and risk taking of organizations—are incorporating some COVID-era practices into post-COVID annual meetings.

At this stage, it is unclear whether the current practices of treating virtual events as supplements to in-person focused conferences signals a commitment to further experimentation or not. For societies, this is a question with significant ramifications. Decisions about conference formats are directly tied to questions about the current and future composition of their membership, the success of organizational commitments to diversity, and the long-term relevance and sustainability of scholarly societies. They are also decisions that will impact the larger landscape of scholarship and scholarly communication.

The present report details findings from a major research project on the future of scholarly meetings conducted by Ithaka S+R and JSTOR Labs in partnership with representatives from 17 scholarly societies and with generous funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. This community of co-learners met regularly throughout 2022 and into early 2023 for strategic discussions and design-informed workshops about the challenges facing scholarly conferences and opportunities for change. Individual sessions within our institute focused on financial models for virtual and hybrid meetings, meeting member needs, working with boards, and a design jam to develop concrete innovations.

Our cohort included 28 individuals, primarily executive directors and meeting managers, from 17 scholarly societies based in the United States. Of these, eight focused on STEM fields, four on humanities, and five on the social sciences, with memberships ranging from around 300 to over 150,000. We are deeply indebted to the individuals who participated, from whom we have learned much and whose participation made this report possible (a full list of participating societies and representatives can be found in Appendix I). However, the findings here should be taken to represent our viewpoint, informed by, but not synonymous with, those of participants. Because our meetings encouraged candor about sensitive topics and heavy doses of speculation about potential strategic directions, we do not attribute ideas to individuals or individual societies in this report.

To an unusual degree, this project was directly shaped by external forces and events. It was conceived during the early months of the pandemic at a time of profound uncertainty and widespread determination to create a “new normal” that would re-evaluate the status quo of when, where, and how work of all types would take place going forward. It launched around the time of the Omicron wave, which served as a blunt reminder of the seriousness of the public health situation, yet most of the institute took place as the effectiveness of vaccines and relaxed regulatory environment created conditions for a resurgence of in-person gatherings across sectors. As we draft this report, the World Health Organization has declared that the pandemic is over, though COVID-19 remains endemic. The mood and tenor of our cohort meetings reflected these shifts. Early meetings were dominated by daily exigencies and the endless need to pivot, improvise, and change plans on the fly. By the end of the institute, staff exhaustion, a sense of excitement about gathering after several years of isolation, and hotel contracts all pushed societies back towards in-person annual meetings. Most members of our cohort shared a conviction that significant changes to the pre-pandemic meeting formats would better position their organization to serve early career researchers—a crucial demographic for membership organizations and for the future of research in the fields societies represent. But the politics of format changes remain daunting—members and boards have strong and conflicting opinions, and tangible financial, technological, and logistical paths forward remain elusive.

If the institute ultimately raised more questions than it answered, it did clarify both the barriers to change and the stakes involved in making them. We wish to highlight four key finding areas:

- Scholarly societies have long traditions of hosting conferences, yet too often convention rather than purpose drives decisions on content and format. Experiments with conference design should begin with a clear articulation of purpose.

- The structure and content of meetings send strong signals about an organization’s priorities and values. Decisions-making about conferences should be calibrated to reflect a society’s mission and goals.

- Making significant changes to meeting formats involves risk, but new conference modalities provide even greater opportunities to increase the impact and accessibility of scholars, build and empower diverse research communities, and improve the sustainability of societies.

- Hybrid conferences are already here, but hybrid is best envisioned as a changeable cluster of possibilities rather than a single format.

Grant Activities

Institute Design

In late 2021, when we began recruiting for the project, the pandemic had disrupted two cycles of annual meetings for most societies. Op-eds assessing the successes and failures of virtual meetings were commonplace and a few early white papers—notably the very useful Presidential Task Force Report from the Association for Computer Machinery (ACM)—had begun to identify best practices and assess tools for successfully planning virtual conferences.[9] Despite this accumulation of evidence, many—perhaps most—societies were still in crisis mode, improvising, reactive, and exhausted by the social, political, and epidemiological upheavals for the previous two years. Time and space for reflection about the previous two years, and for deliberate consideration of what the future might hold, took a backseat to day-to-day challenges.

In the first instance, our goal was to provide this time and space. We aimed to fill this space with leaders and meeting planners from scholarly societies who would meet regularly to learn from each other. We recruited primarily through direct solicitation because we felt it was important that the cohort include societies with widely different membership sizes and resources and a broad range of disciplines: we wanted to maximize opportunities to learn from both close peers and from societies that might otherwise never speak with one another. Including a range of societies would also help make the present report more broadly useful and less likely to mistake domain specific challenges for universal ones, or—as importantly—treat universal challenges as though they were unique to a discipline. A second goal was to leverage the power of design thinking to ground our conversations and promote solution-oriented thinking. To this end, most convenings featured interactive design components such as empathy mapping, futuring, and a design jam.

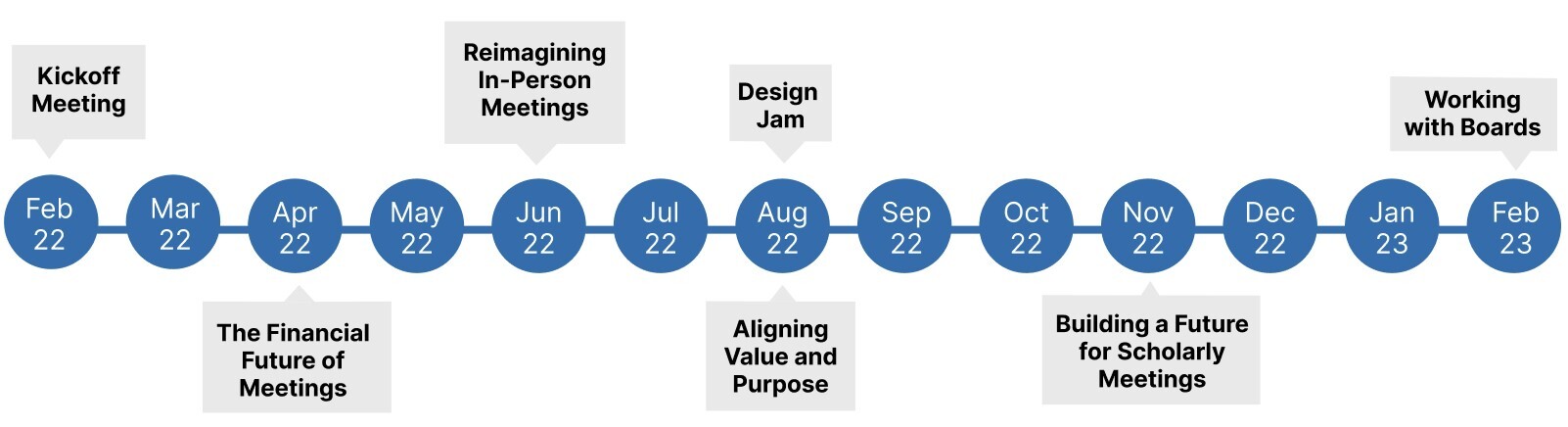

The institute convened seven times over the course of 2022 and early 2023 for a series of working meetings that emphasized discussion and knowledge exchange on a specific topic. All meetings were conducted virtually.

Institute Timeline

Kick Off Meeting (February 2022)

Our initial session was built around two small group discussions. The first focused on articulating why societies host conferences and assessing how their current experiments in virtual or hybrid conferences were accomplishing those goals. The second encouraged participants to consider what they hoped their meetings would look like in the next five to 10 years and identify barriers they would need to overcome in order to realize that vision. At a concluding plenary, we synthesized findings from the breakout rooms to find common questions, goals, and challenges that were shared across the cohort and would guide future institute sessions.

The Financial Future of Meetings (April 2022)

Conferences play major roles in the finances of most scholarly societies, making changes to conference modalities a high stakes endeavor. This is true whether societies treat them as profit centers that subsidize other society activities or budget them as break-even propositions. The highlight of this session focused on using design-informed exercises to identify ways to use virtual meetings as tools for increasing membership, particularly among early career researchers. Using an empathy mapping framework, the cohort considered ways to redefine the value proposition of society membership to encourage early career researchers who attended virtual conferences to join or renew as members.

Reimagining In-Person Meetings (June 2022)

At this session, we circulated six innovative models for in-person meetings with hybrid and virtual possibilities. Participants were asked to select a model that they felt they could reasonably implement within the next two or three years, and a second model that represented a desirable long-term option. We also presented a third scenario to cohort members asking them to respond to the possibility that climate change could drastically limit academic travel in the near future. Most participants agreed that they would continue to hold annual meetings with meaningful in-person components for the foreseeable future. They also agreed that fully hybrid meetings (e.g. where all or most sessions are available to in-person and virtual participation) were neither financially feasible nor likely to provide in-person or virtual participants with positive experiences.

Aligning Value and Purpose (August 2022)

At this session, we presented a synthesis of existing research on conference modalities and of observations from our earlier sessions. We presented several propositions to the cohort as a framework for approaching the upcoming design jam including: a) opportunities outweigh risks, b) hybrid is already here, and c) the basics should be on the table. We concluded with a conversation about what organizational values annual meetings currently reflect and how to better align them with organizational strategy.

Design Jam (August 2022)

During this day-long workshop, participants went through several rounds of sketching ideas for innovations in conferences. Through the process, we were able to identify several “easy wins” that could be readily adopted by many societies and two particularly promising ideas for further development into paper prototypes. JSTOR Labs then spent several months iterating, testing, and refining those ideas into prototypes.

Building a Future for Scholarly Meetings (November 2022)

At our final official cohort meeting, we shared the prototypes developed by JSTOR Labs and considered paths forward that individual societies could take and transformative possibilities that would require collaboration between societies, funders, and other stakeholders to accomplish.

Working with Boards (February 2023)

One critical issue that was uncovered over the course of the institute was the importance of support and leadership from governing boards. Interest in this topic was sufficiently strong that we decided to host an extra cohort meeting on the topic after the formal end of the institute. At this informal meeting, participants shared insights into how to build buy-in among board members for meaningful changes to conference formats.

Findings

Finding Area 1: Scholarly societies have long traditions of hosting annual meetings, yet too often convention rather than purpose drives decisions on content and format. Experiments with conference design should begin with a clear articulation of purpose.

At our initial cohort meeting, we asked participants to describe why they held an annual meeting. Several themes quickly emerged that speak to the primary purposes that conference organizers believe that their meetings provide to attendees: a) a venue for scholarly communication; b) a forum for networking between scholars; c) opportunities for professional development. Participants also articulated a number of benefits that annual meetings provide to their society.

Conferences as Scholarly Communication

The first and most often cited purpose of annual meetings was to facilitate the advancement and dissemination of research—in particular new research—in their field. As organizations dedicated in part to the advancement of a field or discipline, this purpose aligns directly with societies’ core missions. We meet, said one participant, “to share science and move scholarly agendas forward.” Annual meetings serve this purpose in several ways. Primary among them are research panels and poster presentations, which together constitute the bulk of conference sessions. For presenters, panels and posters are opportunities to share emerging research findings with colleagues and to receive feedback from peers that will sharpen their hypotheses and conclusions. Audience members receive early access to cutting edge research, which is often shared at conferences before appearing in print.

Though difficult to quantify, these intellectual exchanges are widely believed to increase the speed of scientific innovation by organizations and individuals who are well positioned to understand how scientific culture and research advance.[10] Societies’ marketing materials frequently describe the value of conferences as a form of scholarly communication, and researchers seem to agree. Respondents to Ithaka S+R’s 2021 US Faculty Survey named attending conferences as an important way they keep up with new research in their field more often than any other method, including reading journal articles.[11] Other studies have found that the majority of conference attendees learn new information and ideas while attending.[12]

The Power of Co-Location

Perhaps unsurprisingly, members of our cohort all agreed that one purpose of a conference is to bring widely scattered academics together in a single space. The concentration of scholars created by an annual meeting provided unique opportunities for networking, socializing, and community building. Members of our cohort were particularly eager to facilitate connections between senior scholars and junior career researchers and, in some cases, academic researchers with colleagues working outside the academy.

Several distinct social benefits of conferences have been described in the literature. Some studies have focused on the role that conference attendance plays in socializing students and early career scholars into the culture and norms of a field.[13] Others have attempted to quantify how many collaborative research projects originate as social interactions at conferences, with results suggesting that conferences increase new collaborations in the neighborhood of 10-15 percent.[14]

Most participants had experimented with a variety of formats and platforms in an attempt to replicate some of the social texture of in-person meetings. Without exception, members of our cohort (and most outside commentators), reported that these efforts had largely failed. While new software continues to come to market, optimism for meaningful solutions to this challenge was low.

Venues for Professional Development

Some societies have long histories of offering career and professional development topics at meetings and through other venues. This is particularly true in fields where societies are involved in accreditation of academic programs and/or professional licensing that requires continuing education credits. However, over the past several decades many societies with annual meetings that have traditionally focused almost exclusively on research are re-allocating resources towards sessions on professional issues and professional development. As one participant noted, their meeting has become “increasingly focused on teaching (as opposed to just research).” The workshops, meetups, panels, and roundtables on teaching and learning that have become prominent features at growing numbers of societies reflect organizational commitments to better serving teaching-oriented members and recognition of the importance of undergraduate education to disciplinary reproduction. Teaching-focused programming is also used to attract new constituencies such as K-12 and community college faculty to the meeting. For similar reasons, societies in disciplines facing steep declines in tenure-track hiring are devoting staff resources and room allocations to host sessions and workshops on alternative career paths and transferable skills.[15] This trend will likely continue as academic positions dry up across disciplines and as private sector employment becomes the largest employer of early career PhDs.[16]

Despite their growing visibility, these kinds of activities still exist at the margins of most annual meetings. Nevertheless, they are instructive in that they provide evidence that there is room for new purposes within the shell of an annual meeting, for adjusting programming in response to changes in the needs of members. On the other hand, the halting pace and uneven adoption of increased career and professional development programming is a good reminder that in the normal course of events, structural change comes slowly to annual meetings.

Financial Models for Meetings

For many societies, the primary purpose of their annual meeting is to generate revenue to support the societies’ mission. Scholarly societies typically organize meetings on one of two major financial models. In a net revenue generation model, annual meetings are priced to generate substantial surplus revenue relative to their operating expenses. That surplus revenue can then be used to subsidize aspects of the society that are non-revenue generating. Cost-neutral models are budgeted to break even. Our cohort was roughly split between societies depending on one of these two models. Disciplinary patterns are hard to discern given our sample size of 17, but it appears that STEM-oriented scholarly societies are somewhat more likely to use conferences to generate surplus revenue than humanities and social science-oriented societies.

For societies focused on generating surplus revenue, changes to the format of the annual meeting have direct and potentially significant budgetary effects across the organization. Cost-neutral models limit immediate budgetary risks (for societies with endowments or investments to cover short term losses), but sustained losses can undermine the organizations’ sustainability. One key barrier to continued experimentation with virtual and hybrid meetings is that the important questions about essential budgetary questions remain unanswered.

In theory, many societies in our cohort would prefer that their meetings be fully hybrid—that is that most or all sessions would be available in-person and via live stream. However, no one was optimistic that this option is viable or will become so any time soon. The problem is not technological. There are plenty of commercial platforms on the market that support hybrid programming, though none have succeeded in creating rich and immersive environments for both in-person and virtual attendees. The bigger challenge, however, is that the costs of live-streaming content from in-person locations are prohibitive. Most annual meetings are held in hotels or convention centers, which charge high prices for video equipment and video personnel. Though societies are sometimes willing to pay to have small numbers of keynotes or high-profile panels, typical research panels are simply too expensive to stream en masse. A meeting manager in our cohort noted that the “cost to content” ratio of hybrid meetings simply did not work. One smaller society in our cohort had experimented with holding meetings in commercial coworking and event spaces, which can greatly lower the cost of hybrid programming, but this option does not scale to the size of mid to large sized annual meetings.

Virtual or mixed-annual meetings raise equally thorny questions, though primarily on the revenue side of the financial equation. How to set viable price points for virtual registration is still unclear—and is complicated by what many members of our cohort described as a widespread belief that virtual events should be free to attend and to present at—because their production costs were nominal. It is true that virtual events are considerably less expensive than in-person events, but they do have costs in terms of both technology and, more significantly, staff time. Societies and other organizations are, in fact, routinely offering free virtual programming—absorbing the costs of a few webinars is well within the means of all but the smallest societies (and even they are more likely to struggle with the labor involved in organizing an event than with the technology costs).

Societies are typically reluctant to provide free access to virtual-only annual meetings. This is true regardless of whether that access is via live-stream or the now common practices of selling temporary access to recordings generated during the meeting. Few societies are in a position to forgo the revenue that virtual access could generate, though opinions varied widely about how much virtual access was worth. In the spring of 2022, Ithaka S+R conducted research to compare in-person and virtual-only conference registration costs.[17] We located 26 societies (23 in STEM disciplines) providing both options and for which registration prices for their forthcoming annual meeting were available. Pricing ranged widely. Some societies charged identical rates in both categories, while others charged much less for virtual-only access. In every case, in-person registration included virtual access at no additional charge. On average, virtual-only access cost roughly 50 percent of the cost of in-person registration.[18]

| In-person registration | Virtual only registration | |

| Average (all societies) | $544 | $268 |

| Median (all societies) | $535 | $245 |

| Range (all societies) | $187 – $899 | $30 – $620 |

| Average (STEM societies) | $596 | $290 |

| Median (STEM societies) | $588 | $280 |

| Range (STEM societies) | $350 – $899 | $30 – $620 |

| Average (HSS societies) | $256 | $147 |

| Median (HSS societies) | $253 | $124 |

| Range (HSS societies) | $187 – $330 | $100 – $240 |

A second consideration is whether virtual and hybrid programming discourages in-person registration and if so, how much. No society in our cohort had solid data on this point, but many expressed concerns. Virtual registration is attractive when it’s additive, enabling attendance for people who would not have otherwise registered. But if individuals who might attend in-person opt for virtual registration, societies will lose vital revenue. Several cohort members also expressed fears that universities would adopt policies requiring faculty to attend and present virtually when possible in order to save money on faculty travel budgets. Such a preference would have dire consequences for the financial sustainability of in-person meetings.

The Power of Convening

The power to convene is perhaps the most important lever societies have for exercising influence over disciplines and disciplinary cultures. This soft power occurs across the lifecycle of annual meetings. Conference selection committees provide both peer review and a means to ensure demographic diversity among speakers and to balance viewpoint and methodological diversity within and across research panels. Often, a portion of the program is devoted to panels and workshops that are organized by society staff, committees, board members, and executive directors to highlight organizational programs, activities, and priorities. Society-organized panels can be particularly effective means of calling attention to professional issues and challenges such as career diversity, sexual orientation and gender disparities within a discipline, and financial threats to the discipline as a whole. Formal codes of conduct, decisions about keynote speakers, the choice of which sessions to highlight in marketing and communication, and even reception themes provide opportunities to shape disciplinary cultures and communities.

This is hardly an exhaustive list of reasons why societies organize meetings. In theory, each might independently serve as the rationale for hosting a conference, though in practice annual meetings have many purposes. Though they may seem obvious once articulated, it was often easier for cohort members to describe what kinds of activities take place at their meeting than to clearly define why they did those things. This was particularly noticeable when we asked the cohort to break the conference down into its constituent parts—panels, keynotes, poster sessions, receptions, exhibit halls, and so forth—and describe specifically how they contributed to the larger purposes of the meeting. Several observed that this was a novel question, that the typical activities of a meeting are easily taken for granted. The logistics of scheduling and the demands of generating content can dominate the planning cycle, which is too demanding to provide much time to reflect on the meeting’s larger purpose and to consider how well familiar session formats are aligned with those goals and with the needs of scholars.

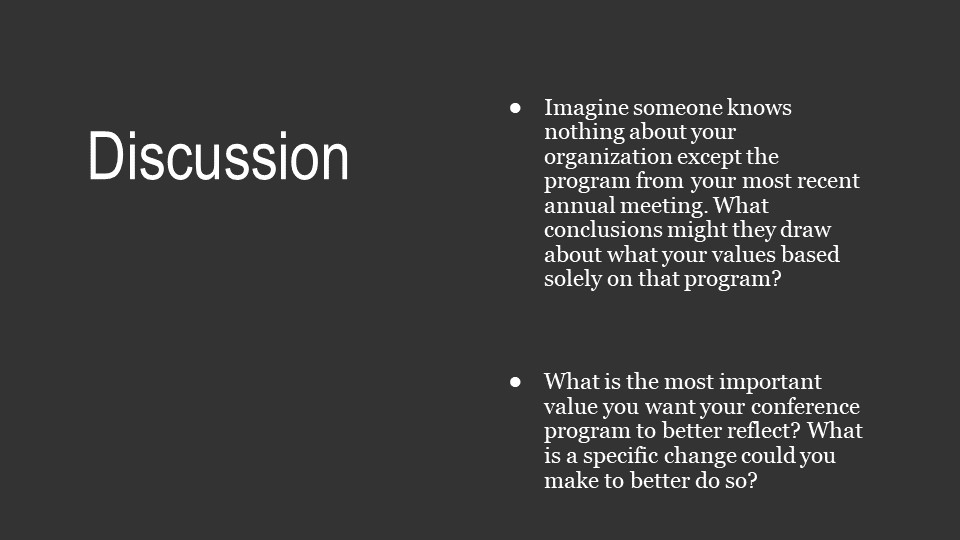

Finding Area 2: The structure and content of annual meetings send strong signals about an organization’s priorities and values. Decisions-making about conferences should be calibrated to reflect a society’s mission and goals.

Annual meetings are the most visible of a societies’ activities—for many scholars, the meeting effectively is the society. The content of a meeting and its cultural norms around belonging and behavior reflect the values and priorities of its organizer. While attendees seldom see the full extent of the labor put into conferences or of the limits within which they operate, they rightly believe the structure, content, and cultural dynamics of an annual meeting reflect the values and priorities of its organizer. Though difficult to quantify, evidence that early career scholars and scholars from minoritized groups often struggle to see their values and needs reflected in annual meeting programs and society activities is easy to find. For example, a recent study of early career researchers in the social sciences noted a “a powerful sense of frustration and disillusionment with incumbent scholarly societies, pointing to an emerging crisis of legitimacy for these organizations.” The same study noted that annual meetings were often “singled out as a particular site of dissatisfaction both with the staid format of the scholarly program and the interpersonal dynamics that tended to prevail.”[19] Concerns about the high costs of attendance and the perceptions that meetings primarily serve the needs of high profile mid to late career scholars, are commonplace among early career scholars. Meanwhile, scholars of color, women, and LGBTQ researchers and other researchers from minoritized groups report widespread microaggressions and acts of harassment that illuminate the boundaries of belonging within scholarly communities and conference cultures.[20]

Annual meetings are the most visible of a societies’ activities—for many scholars, the meeting effectively is the society.

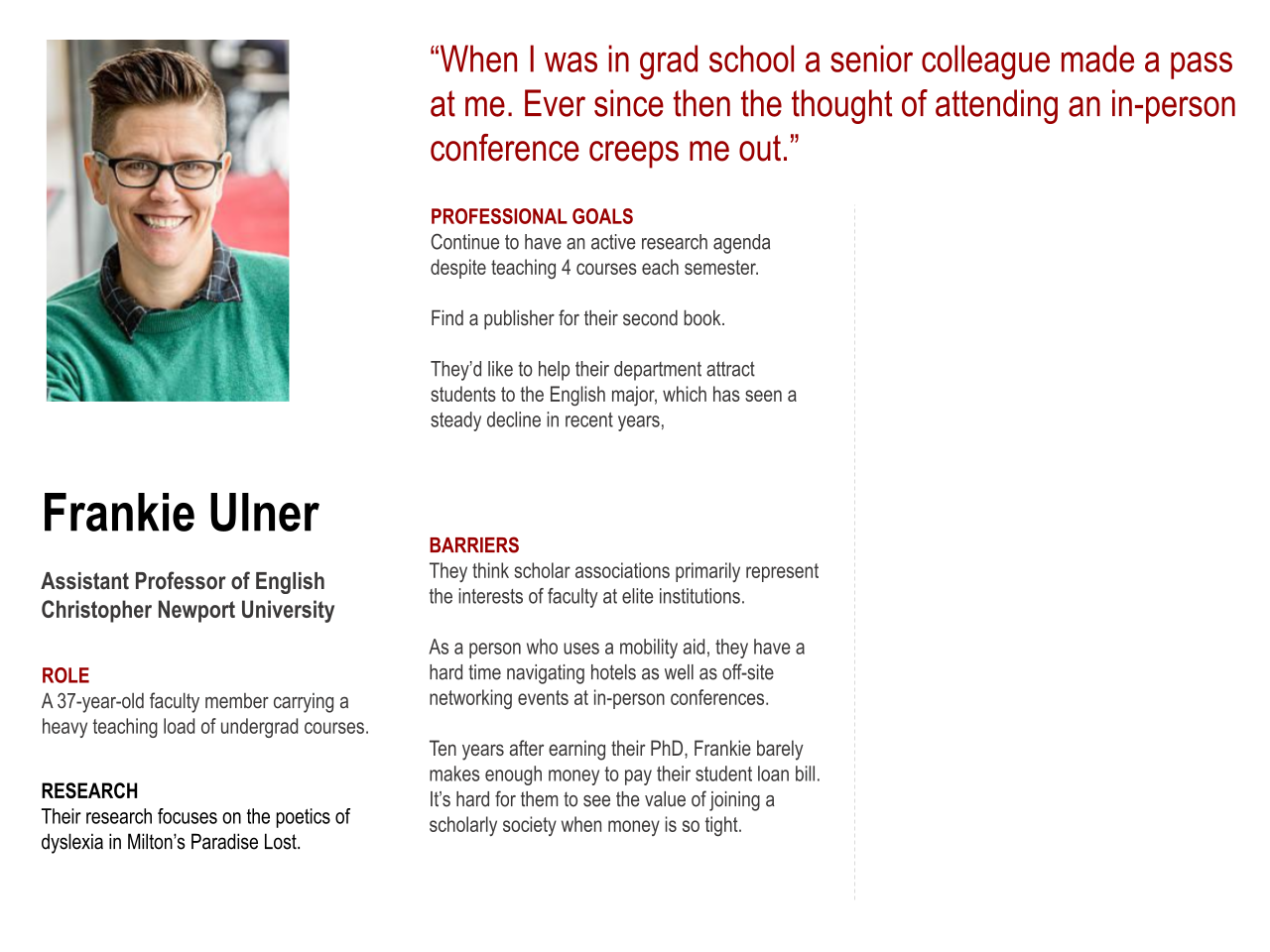

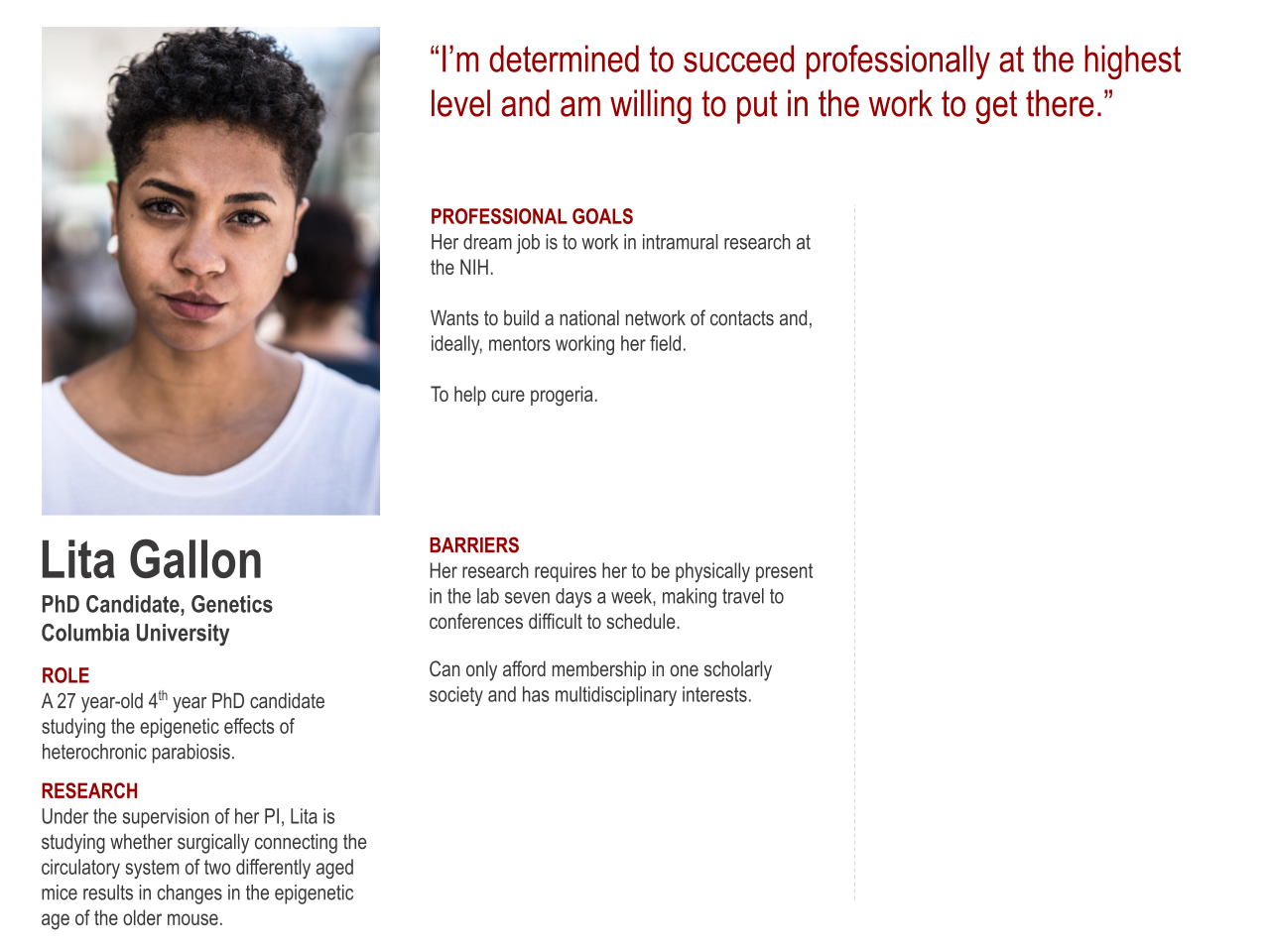

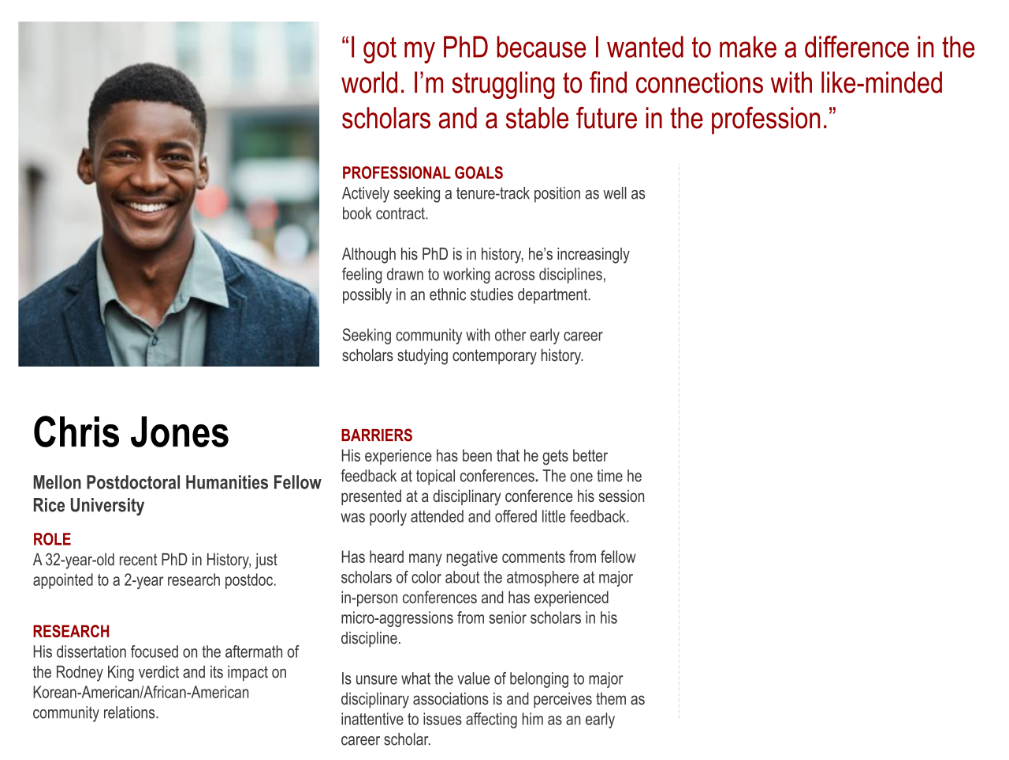

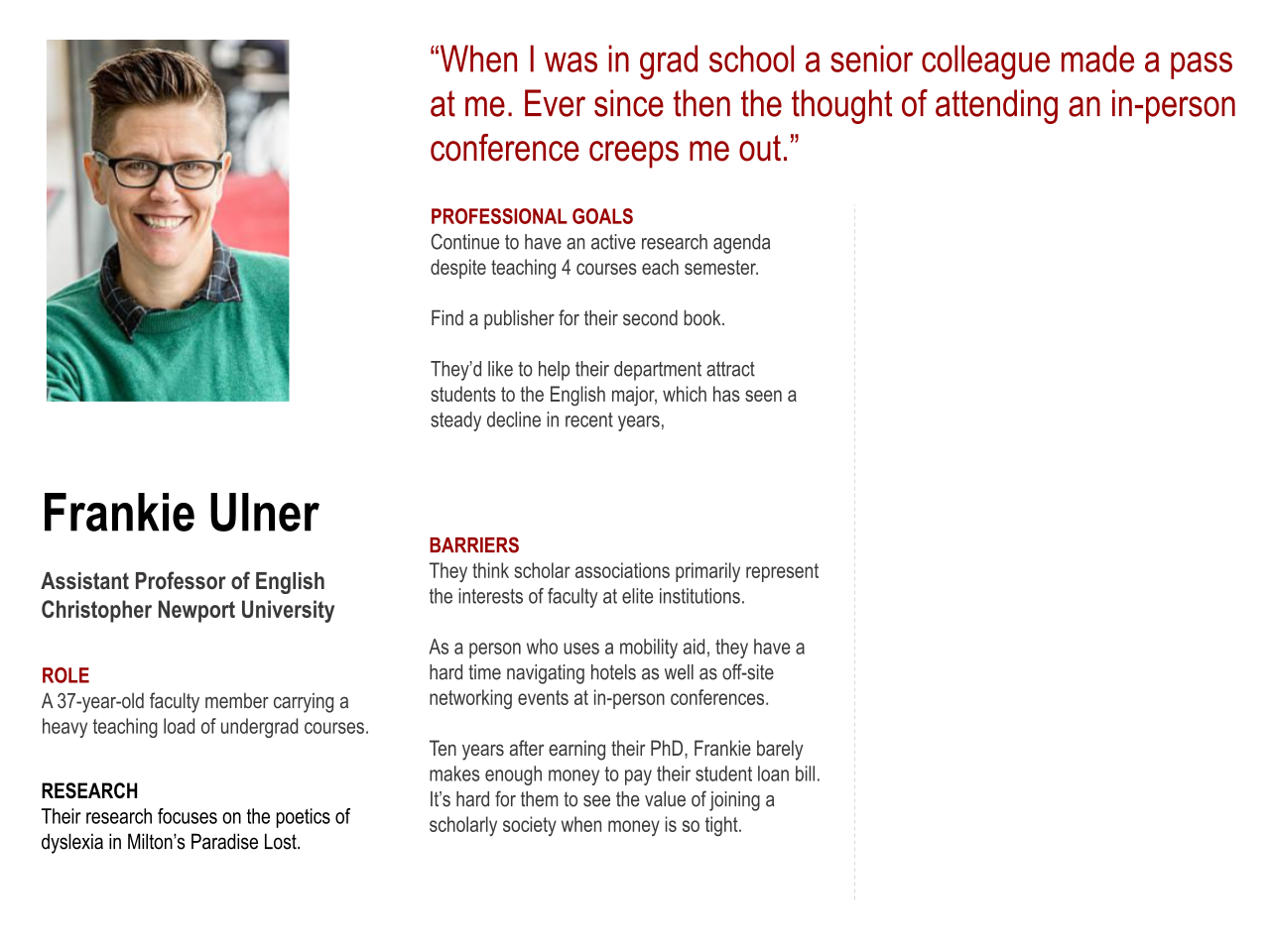

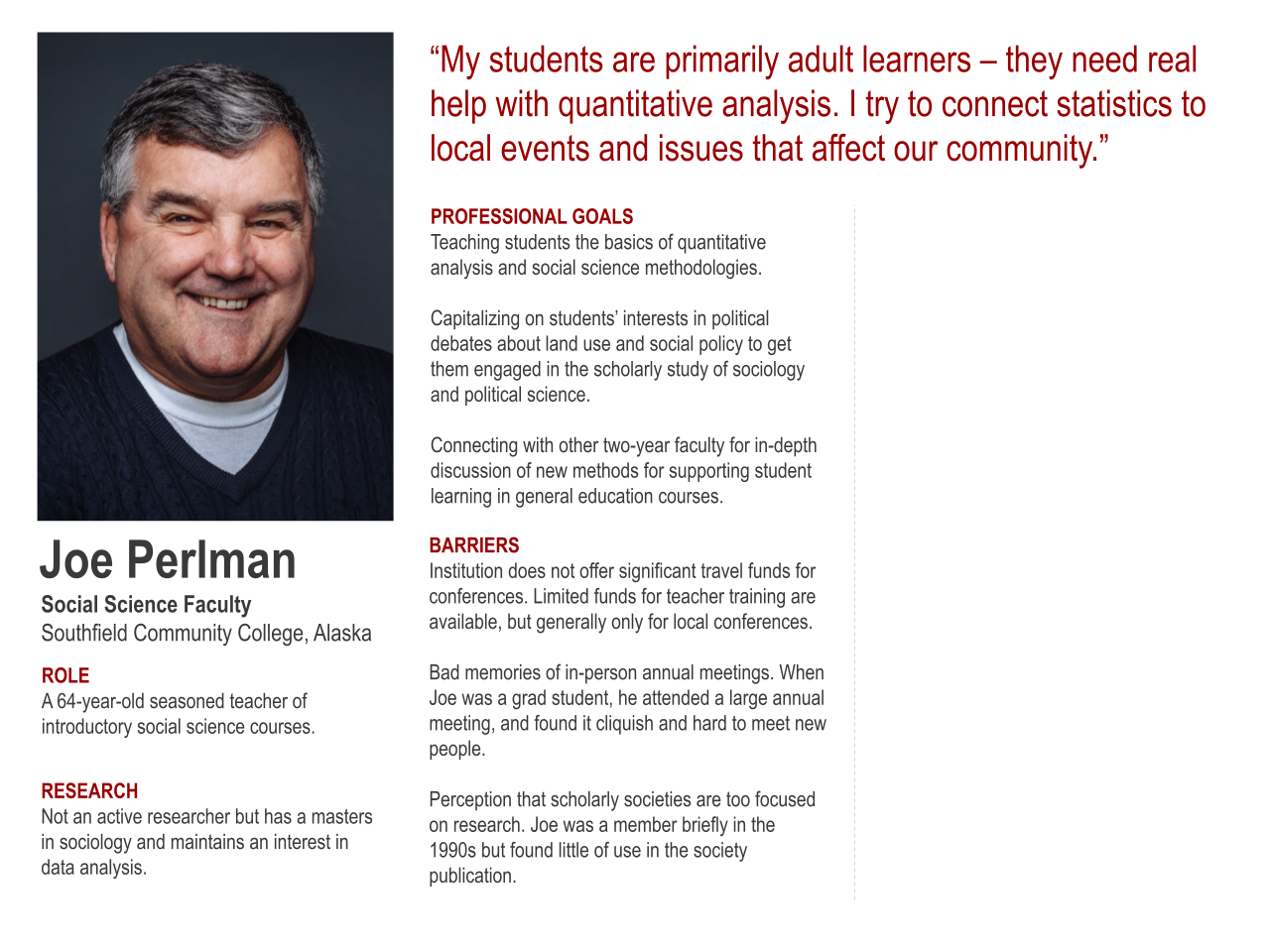

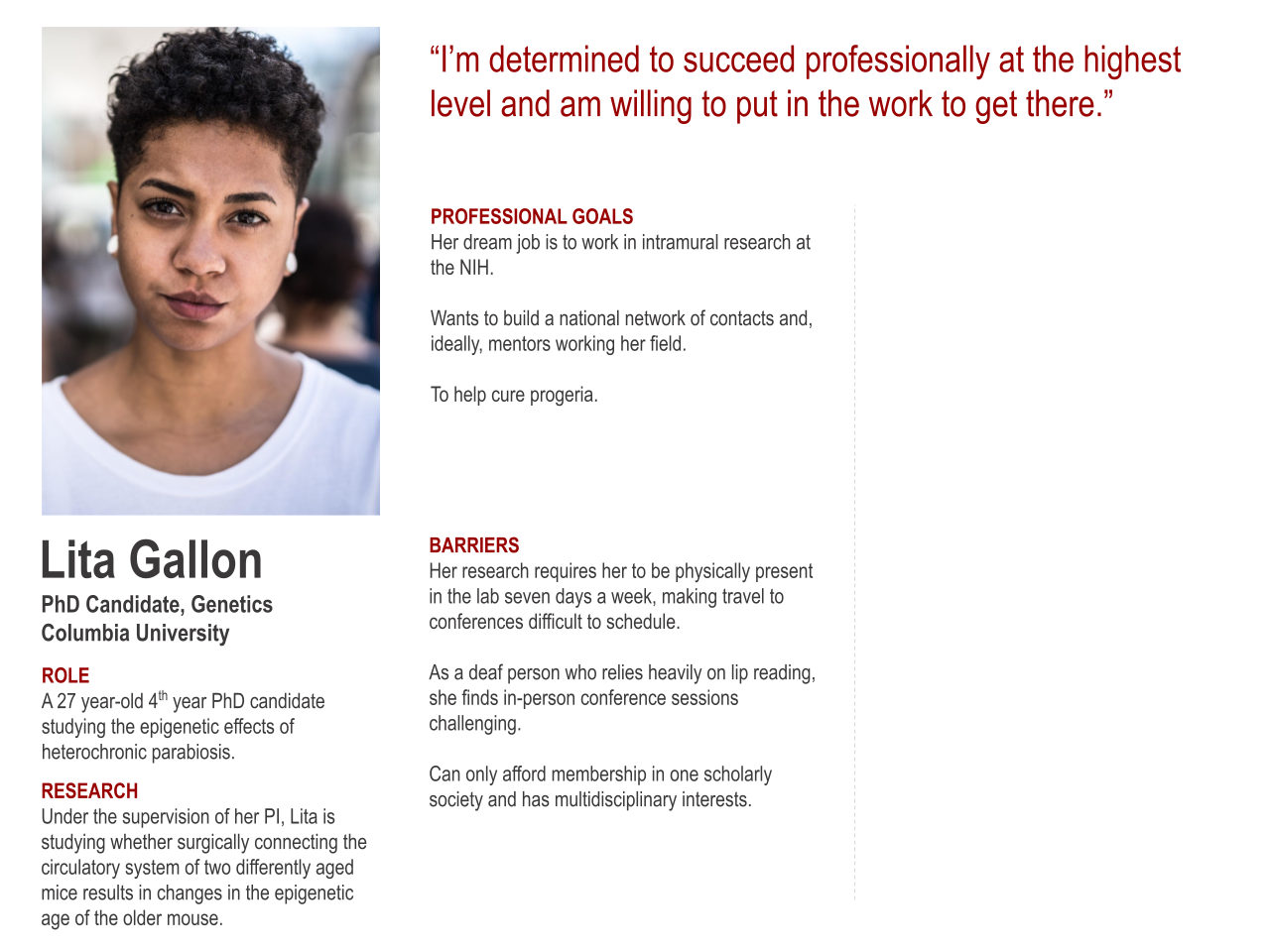

These are exactly the groups that societies are most eager to recruit as members. Early career scholars are the lifeblood of a membership organization: without them, the long-term sustainability of the organization is imperiled. When asked to choose the profile of specific personas for an empathy-mapping activity, the overwhelming majority of cohort members selected early career researchers as the people they most want to attend their annual meeting. Likewise, scholarly societies have made serious commitments to improving the diversity of their membership so that it better reflects the changing demographics of academic communities and furthers equity and justice goals that have become central to many societies’ missions and values.

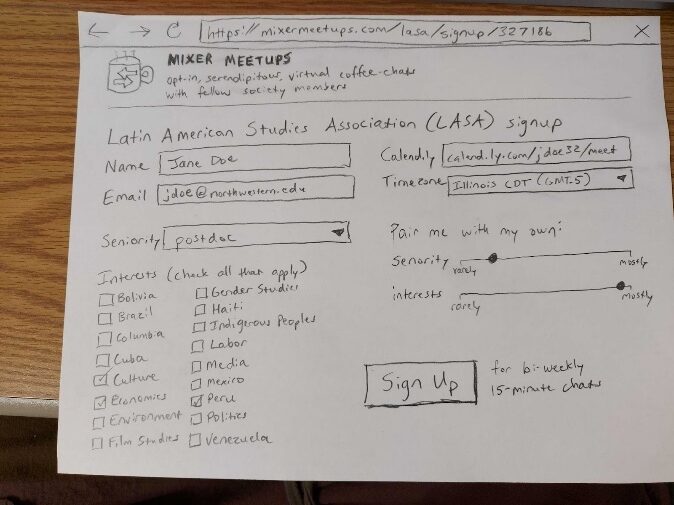

Figure 1: Simulated profiles for use in understanding how changes to meeting formats impact early career researchers

Peer-reviewed research is now backing up anecdotal evidence that virtual conferences are significantly more diverse than in-person ones. A study of participation at five virtual conferences in science and engineering fields found that participation of women increased between 60 and 260 percent. Participation by researchers from either primarily undergraduate or regional research institutions increased between 45 and 157 percent. The elimination of travel costs allowed more students and postdocs to attend as well: as a proportion of all attendees, they grew from 29 to 42 percent and 5 to 11 percent, respectively.[21] A separate study of conferences in biology, computer science, and bioinformatics reported a “dramatic increase in the number of participants from under-represented minorities, as well as in international attendees.”[22] The research is clear: virtual meetings substantially improve access to conferences and attract a much more diverse range of participants than in-person meetings.

Figure 2: Discussion prompt considering a key topic of the institute—the relationship between meeting formats and societies’ values

Scholarly societies that are returning to fully in-person annual meetings are choosing to hold conferences that limit access by the very scholars societies most want to engage. The possible long-term effects of this decision on membership are impossible to know with certainty—but it is very easy to imagine that it could significantly affect the sustainability of many societies. Much more importantly, it sends a message about who societies value and contributes to existing inequities within scholarly communities.

Members of our cohort understood this but were less clear about what to do about it. Many described being caught between in-person only and virtual-only camps, a divide that broke roughly along generational lines. Some had existing hotel contracts that left them with few options, and most are currently trying to split the difference by offering both in-person and virtual formats “at” their annual meeting and/or by developing year-round virtual offerings. Whether this will leave either camp happy remains to be seen, though the attractions of this middle ground approach are obvious and, potentially, offer a significant way for societies to increase access while still holding large in-person conferences.

Decisions about conference formats are decisions about values: like budgets, they speak to an organization’s actual priorities. Societies have multiple competing values and priorities and will figure out how to balance them to the best of their abilities within the limits of their resources. There is no single or simple answer about how to do so. What is important is to center questions about values and priorities in decision making about the future of annual meetings.

Finding Area 3: Making significant changes to meeting formats involves risk, but new conference modalities provide even greater opportunities to increase the impact and accessibility of scholars, build and empower diverse research communities, and improve the sustainability of societies.

For understandable reasons, societies are typically cautious with risk and slow to change. Few have large endowments or other resources to use to recover from a mistake, and the needs and interest of their core members are relatively stable from year to year. The members of our cohort tended to frame significant changes to their annual meeting as a serious risk. The decision making of other societies suggests that the cohort is well-aligned with the thinking of their counterparts in other societies.

In the view of cohort participants, there is a strong generational aspect to this calculation. Senior members of societies tend to have strong preferences for in-person meetings. Societies are hard pressed to ignore that preference: senior members are more likely to serve or have served in key leadership roles and to have accumulated professional prestige. They are also likely to renew their membership and to be considered as potential donors. Societies have compelling reasons to be responsive to these members: they are the foundation of their membership base and as membership organizations, serving the needs of members is part of the core purpose of a scholarly society. Several members of our cohort remarked that because multiple scholarly societies exist in most fields, senior members could readily find a new “home” society if their current one de-emphasizes the in-person meeting. One participant indicated that some members had explicitly communicated this possibility.

Exhibitors also prefer in-person meetings, and the revenue that exhibit halls generate is important to most societies. Both the literature and the experiences of our cohort members agree that existing virtual conference models offer significantly less value to vendors, though a few members of our cohort reported modest success with finding sponsors for high profile virtual programming.[23] In-person exhibit halls attract large numbers of passersby, while virtual exhibit halls are lightly attended. The marketplace may eventually solve this problem, but innovation in this space has slowed as the pandemic has waned. One of several CEOs with whom we spoke during the course of this project observed that the private sector was largely failing to articulate the value of virtual meetings and to price products at levels that societies can afford.

The future of conferences is also a question about the future of membership.

However, from an outsiders’ perspective, societies may be underestimating the risks of inaction. As we have seen, fully virtual meetings have changed the demographics of conference participants in ways that better reflect the future of scholarly communities. Many societies are already struggling with an aging and shrinking membership. Long-term membership data is difficult to find, but available evidence demonstrates that these declines can be significant. The American Sociological Association saw a 22 percent decrease in members between 2007 and 2017, when an ASA task force charged with increasing membership pointed to the annual meeting as one of three critical areas in need of change. By 2022, membership had declined by an additional 14 percent.[24] Not all societies face declines of this magnitude, but overall, membership in societies is on the decline. Wiley, which conducts annual surveys of society membership, reported an 8 percent decline in membership in its 2022 survey, and noted that the percentage of researchers who belonged to a society was now at the “lowest level of society membership since we started the survey nine years ago.” 71 percent of those 31 years or more into their career belonged to a society. In contrast, only 32 percent of early career researchers and 28 percent of students were society members, and noted that skepticism about societies’ commitments to diversity, equity and inclusion was a significant factor in their decision-making around membership.[25] Societies are aware of and concerned by these trends—it was a consistent topic of conversation throughout the institute.

In our estimation, this is perhaps the most powerful argument for boldness in decision making about conference formats. The cautious and slow pace of change that is most comfortable to many societies may often serve societies well, but with regards to the future of conferences, it involves considerable risk. To drift back towards conferences with strong resemblance to the pre-COVID status quo is to miss opportunities to leverage a format that appeals to future members. The future of conferences is also a question about the future of membership.

Planning for Disruption

COVID-19 exposed the fragility of the old normal, leaving societies—and nearly everyone else—flatfooted and off guard. Distant and abstract risks became all too close and tangible and flexibility more important than well-defined structures. Between the possibility of another global pandemic, the acceleration of the climate crisis, and rising geopolitical tensions, there are few reasons to believe that the new normal will be more stable than the old. If anything, it seems likely to be much less stable. As societies build templates for post-pandemic conferences, they would be wise to plan for disruption and make decisions now that facilitate flexibility in the future. One obvious way to do so is to continue building capacity for virtual and hybrid events.

Prior to the pandemic, concerns about the heavy carbon cost of academic travel drove most advocates of virtual meetings. Modern academic life is deeply dependent on air travel and a significant contributor to the carbon footprint of universities. Estimates vary about how high the carbon costs of academic travel are, but individual institutions in the US have estimated amounts ranging from 5-10 percent of total emissions to as high as a third of their emissions.[26]

Conference format decisions can substantially reduce emissions by providing hybrid and virtual opportunities to participate and/or making use of multiple host cities.[27] However, these offerings will need to be of high quality and of comparable prestige in order to maximize their benefits, as scholars—especially those seeking promotion and tenure—have strong incentives to prioritize the prestige of the venue over carbon costs when selecting where to present their research. At the moment, societies have the opportunity to adopt these measures voluntarily: in the future carbon taxes, university or funder decisions to limit or stop funding air travel, and other circumstances beyond their control may force societies’ hands.

Our cohort often identified emissions reductions as a benefit of virtual meetings, but typically ranked it very low on the list of items that was motivating them to invest in the format. In an effort to reframe climate change as an active risk rather than a passive benefit of conference planning decisions, we interrupted one of our cohort meetings and presented participants with a scenario that was not included on the meeting agenda:

The year is 2027. Planet earth has just passed the 1.5 degree Celsius warming threshold—a little earlier than scientists had predicted. The increasingly severe effects of climate change result in a massive shift in economic priorities throughout the globe as governments scramble to manage climate refugees and develop infrastructure to protect resources. Military builds up as competition for resources escalates to a critical rate. To fund these efforts, the US government implements a heavy carbon tax that makes regular airplane travel prohibitively expensive for most individuals.

Universities respond by adopting policies that prohibit reimbursement for travel by faculty. Alternative transportation infrastructure is in the early stages of development, and at least a decade away from allowing for widespread travel. The new economic priorities mean that no financial support is available for scholarly societies for general operating expenses. There will be no federal spending similar to that offered during COVID to keep societies afloat.

In such a scenario, we remarked, scholarship and scholarly communication would likely be even more important than they are now, but scholarly societies would find their power to convene severely constrained. How, we asked, would this affect societies’ ability to fulfill their organizational missions? What would they need to do to adapt, and what could they do now to make those adaptations easier?

Figure 4: Planning for climate disruptions

With one exception, participants agreed that something like this scenario was reasonably likely and that it would put immense pressure on their organizations in general and their meetings in particular. Few were preparing for such a scenario, though. They faced more pressure from members advocating for the return of in-person meetings and of hypermobile academic cultures than from members demanding that their society adopt urgent climate action. In truth, most seemed relieved that they did not face immediate pressure to adapt given their limited financial resources and the exhaustion of their staff after several very difficult years. Most felt that the investment required to mitigate the risks of future disruptions was less urgent than the risks of a poorly attended annual meeting, or universities would see continued investments by societies in virtual programming as an opportunity to decrease or eliminate faculty travel funds, or any number of more immediate problems. Should another disruption occur, they felt confident they could more easily switch to virtual formats if necessary.

Finding Area 4: Hybrid conferences are already here, but hybrid is best envisioned as a changeable cluster of possibilities rather than a single format.

Emerging Conference Formats

In common usage, virtual, in-person, and hybrid meetings form a relatively simple taxonomy for meeting formats. Within this taxonomy, “hybrid” provides a way out of the binary of fully in-person or fully virtual meetings, a way to think of conference options in terms of both/and rather than either/or. In theory, a fully hybrid conference would allow virtual and in-person participants to intermix freely at all or most conference proceedings. To the extent that hybridity depends on the ability of live and remote participants to interact in real time, hybrid meetings are, and will likely remain rare because few societies have the staffing and financial resources to organize them. If hybridity describes meetings with mixed modalities for engagement, most in-person focused annual meetings are now hybrid to some degree.[28]

The most common hybrid meeting format is the parallel meeting. Parallel meetings include both virtual and in-person programming operating on separate tracks. They may be organized essentially as consecutive meetings—for example, an in-person meeting with virtual panels held after the in-person meeting ends, or concurrent meetings, where virtual and in-person events are happening simultaneously. In either version, recordings of selected content from in-person and of all virtual presentations can be made available afterward, usually for a limited period of time and behind a paywall.[29]

Parallel meetings are the easiest and least expensive type of hybrid meeting to organize since they minimize the need for live streaming. They also allow societies to avoid having to make decisions that will alienate member factions, since those with the means and inclination to travel can meet in-person, while those without them still have options for participating or attending.

Parallel meetings are the easiest and least expensive type of hybrid meeting to organize since they minimize the need for live streaming. They also allow societies to avoid having to make decisions that will alienate member factions, since those with the means and inclination to travel can meet in-person, while those without them still have options for participating or attending.

On the other hand, parallel meetings provide only a shallow hybridity. Their relative simplicity and inexpensiveness is a byproduct of their design, which makes little to no effort to facilitate interaction between live and remote participants or to ensure that all participants have equitable conference experiences. The format also presents distinct risks of further entrenching some of the academic inequities of traditional in-person conferences while diminishing the democratizing potential of virtual meetings. It is easy to imagine them splitting into a de facto high status in-person track with rich networking opportunities and unique opportunities for collaboration, and a bare-bones virtual track that becomes viewed as a “lesser” presentation. The pandemic had the salutary effect of reducing pre-pandemic perceptions that virtual presentations were worth less than in person ones. Long-term reliance on parallel meetings could revive them.

Most societies in our cohort were organizing parallel meetings of some type for their 2023 annual meetings and anticipated relying on the format for the next several years. Four societies intended to stick with the format over the long run, several out of the conviction that it was the best way to balance demand for in-person meetings while offering alternative access options that could increase participation. At least one member showed considerably less enthusiasm for the format but did not believe any other option was realistic given the organization’s resources. For the most part, though, participants saw the parallel meeting as a transitional offering rather than a desirable long-term option. The long-term desirability of parallel formats was one of only a few areas where our cohort clearly split along disciplinary lines. No STEM society expressed long-term interest in the format, while the majority of humanities societies did.

Every member of our cohort was committed to retaining in-person focused annual meetings, though two societies were exploring rotating between fully virtual and fully in-person meetings on alternate years.[30] All of them anticipated that for the foreseeable future those meetings would include hybrid components.

Opinions varied widely as to what those meetings would look like. At our June 2022 meeting, we asked participants to choose what they wanted their annual meeting to look like 10 to 15 years from now from several emerging conference formats: parallel, hub and spoke, distributed, seminars, and multidisciplinary topical summits. We have described parallel meetings already, but the remainder deserve brief introductions.[31]

Hub and Spoke. Regional conferences (“spokes”) meet concurrently with a central in-person conference (the “hub”), creating connected mini-conferences in local settings that supplement a flagship central meeting. The society organizing the committee would likely take primary responsibility for organizing the hub meeting, providing content and support to link the spokes, while local organizing committees would take responsibility for organizing in-person and/or virtual events for meeting spokes, as well as assisting in linking their content to the central meeting hub.

Distributed. This conference model consists solely of regional meetings that are linked conceptually and temporally but are otherwise largely autonomous. Distributed meetings could be largely distinct from one another but might also be connected through virtual programming or hybrid cross-meeting sessions.

![]()

Multidisciplinary Topical Summits. In this model, societies co-organize multidisciplinary meetings organized around specific themes. They may include traditional panel presentations but are likely to benefit from increased emphasis on networking and as forums for working groups to meet, collaborate, and share. For example, ecologists, geologists, agricultural scientists, economists, and oceanographers could jointly organize a summit on the topic of water.

Seminars. Another alternative to discipline-spanning generalist meetings, the seminar is similar to the multidisciplinary summit in that it is focused on a specific theme, though its scale is likely to be considerably more modest. Seminar-style meetings could be organized regularly as a series of options that meet in a variety of physical and virtual spaces. Alternatively, a society could organize several such seminars that would be held concurrently, to create something resembling a traditional in-person meeting focused on seminar meetings rather than panels.

At least one society preferred each of these options, highlighting the likelihood that societies will make different decisions about their meetings that reflect their missions and resources. One individual described topical summits as “a best-case scenario” because they created opportunities for cross-society partnerships. For smaller societies, the individual said, this kind of collaboration represented a clear long-term path to sustainability. A different individual favored distributed conferences, because of their reduced carbon footprints and because they might foster meetings that were “more intimate and therefore more enriching when it comes to interacting with colleagues.”

However, the two most common choices were parallel meetings and the hub and spoke model. The benefits of the hub and spoke were described in several ways. One participant described them as ways that the national society could interact more with their regional chapters. Another imagined coordinating spokes around the world, where the spokes could contribute to “building strong research communities in areas of the world that are economically challenged.” This global vision was reiterated by other societies from STEM fields in particular, who are already accustomed to thinking about global research networks but face difficulties bringing those communities together at a single location due to travel costs and visa issues. By adding virtual spokes and/or streaming selected panels from hub to spoke, spoke to hub, or spoke to spoke, the model offered some ways to replicate the communal feeling of a fully in-person conference and to avoid marginalizing virtual participation. The hub and spoke model has also been proposed by advocates for reducing the carbon footprint of annual meetings.[32]

Actually implementing a hub and spoke conference presents several challenges. Creating a coordinated event spread across locations (especially if distributed across the globe) adds several additional layers of complexity to the already complex logistics of organizing an annual meeting. While local chapters or organizing committees could help plan the spoke meetings, several societies were protective of their brands and expressed concerns about meetings that they had not planned being organized in their names.

These and other hurdles may limit the practicality of the format for many societies: while many cohort members found it intriguing, just one or two were actively discussing how to implement it. The relative simplicity of organizing parallel meetings may discourage further innovation. Several societies in the cohort already seem content to settle on it, and absent sustained will and commitments from leadership, many other societies are likely to do so as well.

Reimagining Conferences Sessions

Our cohort and this report, like most discussions of conferences before and after the pandemic, has focused on the whole rather than the parts. One reason for this is that the parts are so easily taken for granted. Indeed, with the exception of receptions and other social events, which have seen considerable experimentation over the past several years, most virtual and hybrid meetings have mirrored in-person conferences as closely as technology allows, importing old formats into radically different technological contexts. Some of these formats, most notably the three or four paper panel, are frequently derided even at in-person events and yet have been transported essentially unchanged into virtual formats, where they are no less vibrant (but at least essential to sneak away from or multitask through).[33] As they exist now, most virtual and hybrid offerings function as either substitute for or supplement in-person meetings, largely the same except that one takes place in a room and the other on Zoom.

As they exist now, most virtual and hybrid offerings function as either substitute for or supplement in-person meetings, largely the same except that one takes place in a room and the other on Zoom.

Meeting planners have deep understandings of what purposes the various sessions and events at conferences serve. Early in our design jam, we broke participants into small groups to discuss the purpose of five conference activities: plenaries, poster sessions, panels and roundtables, receptions, and exhibit halls. At first, the question threw many participants for a loop: several mentioned having never been asked it before. Despite this, each group rapidly identified distinct and consequential ways that each of these events contributed to the larger goals of the annual meeting. Consider, for example, the differences between plenaries and panels. Both are forums for scholarly communication, but their roles diverge. As a participant succinctly noted, the key difference between plenaries and panels is that plenaries are “less focused on the value they give to presenters” and more focused on the “value they give to the society and the audience.” For the most part, they are content with the alignment between purpose and form.

In contrast, we have barely begun to consider what new types of content would maximize the affordances of virtual and hybrid meetings or of what alignment between purpose and form would look like. What would born-digital conference sessions look like and be able to do? In what ways could societies build session formats that served the core purposes that in-person sessions serve, but without replicating their form? How might they be better at facilitating scholarly communication and exchange, fostering scholarly communities, and encouraging the advancement of science than legacy formats? What transformations would be required to equip them to do so? We won’t understand the value of virtual and hybrid formats until we have designed conferences that take advantage of the technological gap that separates the nineteenth from the twenty-first century.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that the early optimism that we would see a revolution in conferences has fared little better than the idea that the “new normal” would differ significantly from the old. Three years of conversation—within and outside our cohort—have produced little in the way of solutions to the problem of creating vibrant social interactions in virtual settings, of how to pay for hybrid meetings, or a way out of the stalemate between those who prefer either virtual or in-person formats. One path forward might be to concentrate on the parts rather than the whole, and experiment boldly with what those formats could be if freed from the conventions of the traditional annual meeting.

Conclusion

Lurking under these issues is an even larger one that we have not yet raised. What is the purpose of a scholarly society in the twenty-first century? Declining memberships and the sense among a significant number of early career researchers that societies are at best indifferent to their needs are indications that many scholars are also asking this question.

Many societies are struggling to articulate their value proposition to members. More than a few members of our cohort considered this an urgent challenge for which they did not yet have a satisfactory answer. Membership pages on society websites sometimes spend more time listing member benefits than making the case for the value of the organization itself. Among the member benefits that societies most often highlight is the opportunity to participate in their annual meeting. In doing so they also highlight the depth of the relationship between meetings and members as well as the interconnections between the purpose of societies and the purpose of meetings. Clarity regarding the purpose of societies and their meetings is the fulcrum upon which the survival of societies may balance.

Recommendations

Societies

- Increase experimentation with maximizing the possibilities afforded by virtual and hybrid events. Many societies now regularly produce virtual content that is not attached to the annual meetings: encourage presenters and staff to use the medium to its fullest rather than hew closely to legacy formats.

- Make conscious decisions about conference modalities rooted in the missions, values, and goals of your society. Returning to fully in-person meetings may be a reasonable decision for some societies: the real danger is that societies will simply drift back into them.

- Decisions about format are decisions about which members or potential members’ needs to prioritize. Those decisions should be made with the long-term sustainability of the organization and the future needs of scholarly communities in mind.

- Design decisions about the shape of entire meetings and of individual sessions should begin with consideration of what outcomes they are designed to accomplish.

- Don’t give up on virtual formats. While the demand for in-person meetings is ascendant, it will take several more years before it is possible to have a clear idea of the actual demand for virtual and in-person formats. Recent data is too tied to the ebbs and flows of the pandemic to be definitive.

- Many societies make decisions based on small numbers of highly vocal members, rather than evidence-based assessments of what their members and potential members want and need. Invest in surveys and other ways to develop data about members and non-members’ needs and desires.

- The most urgent research problems cannot be solved through single disciplines. Societies should work now to create models for conferences and other activities that support convergent and interdisciplinary research and allow societies to pool risks and costs.

Scholars

- Societies are by nature more responsive to the needs of members than non-members. Advocacy for virtual or hybrid meetings, robust DEI and justice initiatives, climate change, and other reforms to societies will be more effective if it comes from members.

- When creating presentations, consider whether legacy formats best suit your goals and make best use of available technology.

- Consider committing to making meaningful changes to your travel patterns and limit in-person participation.

Funders

- Absent strong pressure from outside forces, many societies are likely to more-or-less return to pre-pandemic conference formats and miss the opportunities that the pandemic afforded to make meetings better aligned with the technologies, scholarly communities, and research questions of our times. Funders are well positioned to push societies to continue innovating in this space.

- Fund carbon offsets and incentivizing emissions reducing behaviors among grantees.

- Find opportunities to invest in community infrastructures to make the financial costs of hybrid meetings viable. Support and encourage cross-societal experimentation with consortial meetings.

- Consider whether new models for scholarly association may be needed. Consider funding operational grants to societies willing to take the risks associated with experimentation. Likewise, promote other forms of voluntary association that may be better able to adapt to present and future circumstances.

Appendix 1: Participants

American Arachnological Society

Andy Roberts, President

American Association of Geographers

Oscar Larson, Director of Meetings

American Geophysical Union

Lauren Parr, Vice President, Meetings

Rebecca Orens, Assistant Director, Meetings Experience

American Historical Association

Dana Schafer, Deputy Director

Debby Doyle, Meetings Manager

Hope Shannon, Marketing and Engagement Manager

American Philosophical Association

Amy Ferrar, Executive Director

Melissa Smallbrook, Meetings Coordinator

American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

Roya Jaseb, Director of Meetings

Ann Brameyer, Meetings Manager

American Society of Civil Engineers

Elizabeth Maddox, Director of Conference and Event Services

American Society of Plant Biologists

Sarah Black, Vice President for Content and Communications

Jean Rosenberg, Director of Meetings and Events

American Sociological Association

Nancy Kidd, Executive Director

Michelle Randall, Director of Meetings

American Statistical Association

Donna LaLonde, Director of Strategic Initiatives Outreach

Naomi Friedman, Meetings Planner

Bibliographical Society of America

Erin McGuirl, Executive Director

Ashley Cataldo, Events Chair

Genetics Society of America

Tracey DePellegrin, Chief Executive Officer

Middle Eastern Studies Association

Jeff Reger, Executive Director

Mormon History Association

Barbara Jones Brown, Executive Director

Christine Blythe, Executive Director

Greg Golding, Production Consultant

Population Association of America

Danielle Staudt, Executive Director

Bobbie Westmoreland, Program and Education Manager

The Oceanography Society

Jennifer Ramarui, Executive Director

The Protein Society

Raluca Cadar, Executive Director

Appendix 2: Empathy Mapping Personas

Empathy mapping is a common component of design thinking used to understand users’ behaviors and needs. We used this activity to ground conversations about the effects of decision-making about conference formats on specific types of scholars that our cohort identified as of high interest. The following personas were generated to represent realistic, but fictitious, scholars whose needs, values, and goals could be tested against proposed courses of action.

Appendix 3: Conference Modality Cards

These “cards” were prepared in advance of a cohort meeting focused on possibilities for reimagining conferences that featured significant in-person programming. Participants were asked to select two options from these cards that seemed most promising in the short-term and long-term for their society.

Appendix 4: Design Jam

The cohort, along with several ITHAKA staff and early career scholars, participated in a “design jam,” sometimes known as a “design studio.” A design jam is a method of structured brainstorming by way of sketching. First, we reviewed our understanding of scholars’ needs, with a particular focus on the needs that aren’t being met well by societies. We asked everyone to sketch as many small concepts, up to eight on a page, as they could within eight minutes. Then, we shared those sketches on a Mural board and the sketcher explained their thinking to the group.

We asked everyone to sketch a second round of ideas, keeping in mind any inspiration from the first round that they could build on. Finally, we asked them to vote with colored dots to indicate the ideas they believed to have the most potential. The second round of ideas, with votes, is depicted below.

Based on the sketches and votes, we came away with five ideas we believed to be promising and worth further evaluation. We sketched those five concepts on paper and tested them with seven society staff members in September 2022. These ideas, along with the high-level findings about their feasibility, desirability, and viability are described below.

The first three concepts were only tested once.

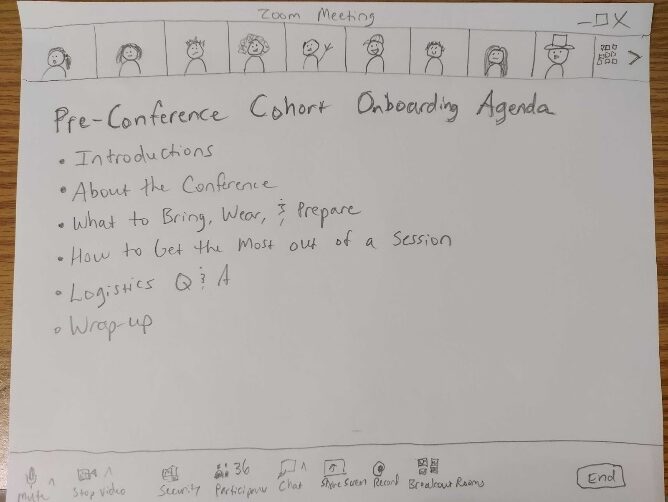

Pre-Conference Zoom Cohort Onboarding

In this concept, new society members who are attending the conference for the first time are granted an opportunity to meet beforehand to network with other new attendees and learn about how to prepare for the conference, such as what to expect and how to get the most out of it.

The response to this concept was overwhelmingly positive in large part because it’s an easy win.

So easy, in fact, that all but one society had either adopted it or was in the process of adopting it. The minimal downsides of this idea seemed mostly related to the advisor-advisee relationship. For instance, the advisor might view this conference prep as their job, or the advisor may control which sessions the advisee attends. While this idea was well received, it isn’t particularly innovative since it had already been implemented by many societies; we didn’t take this concept any further.

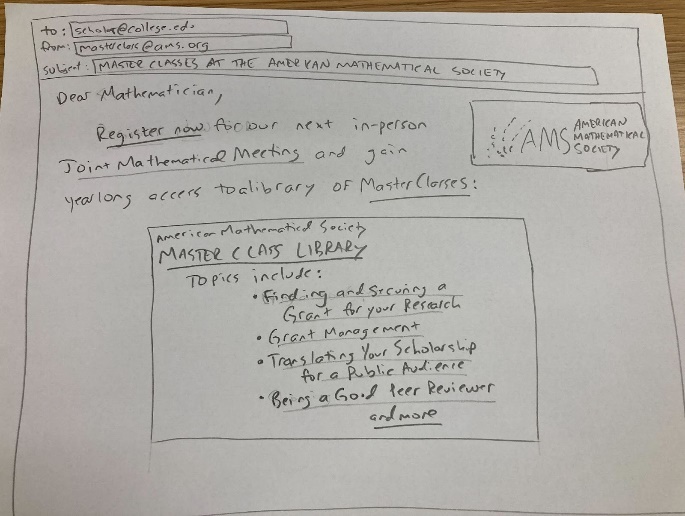

Master Class Library

In this concept, a society hosts a collection of online meta-scholarship presentations on topics such as how to secure grants, how to translate your research for a public audience, or how to be an effective peer reviewer.

Interviewees particularly liked the name “Master Class Library.” In many cases, they already had video collections of talks from leaders in their fields online, though these were more often about scholarship than the meta-scholarship topics mentioned above. The latter were considered especially valuable for professional development purposes. Besides the name, another innovative aspect of this concept was the access model. Registering and paying for attendance at the in-person conference would grant access to this library for a year. As it is, most societies’ video collections either seemed to be free or tied to membership.

Some concerns about this topic included a) the “minefield” involved in selecting who would be chosen to speak, and on which topics b) the need to pay speakers to record the videos and c) the idea that these topics would be better covered through in-person—or at the least more interactive—sessions.

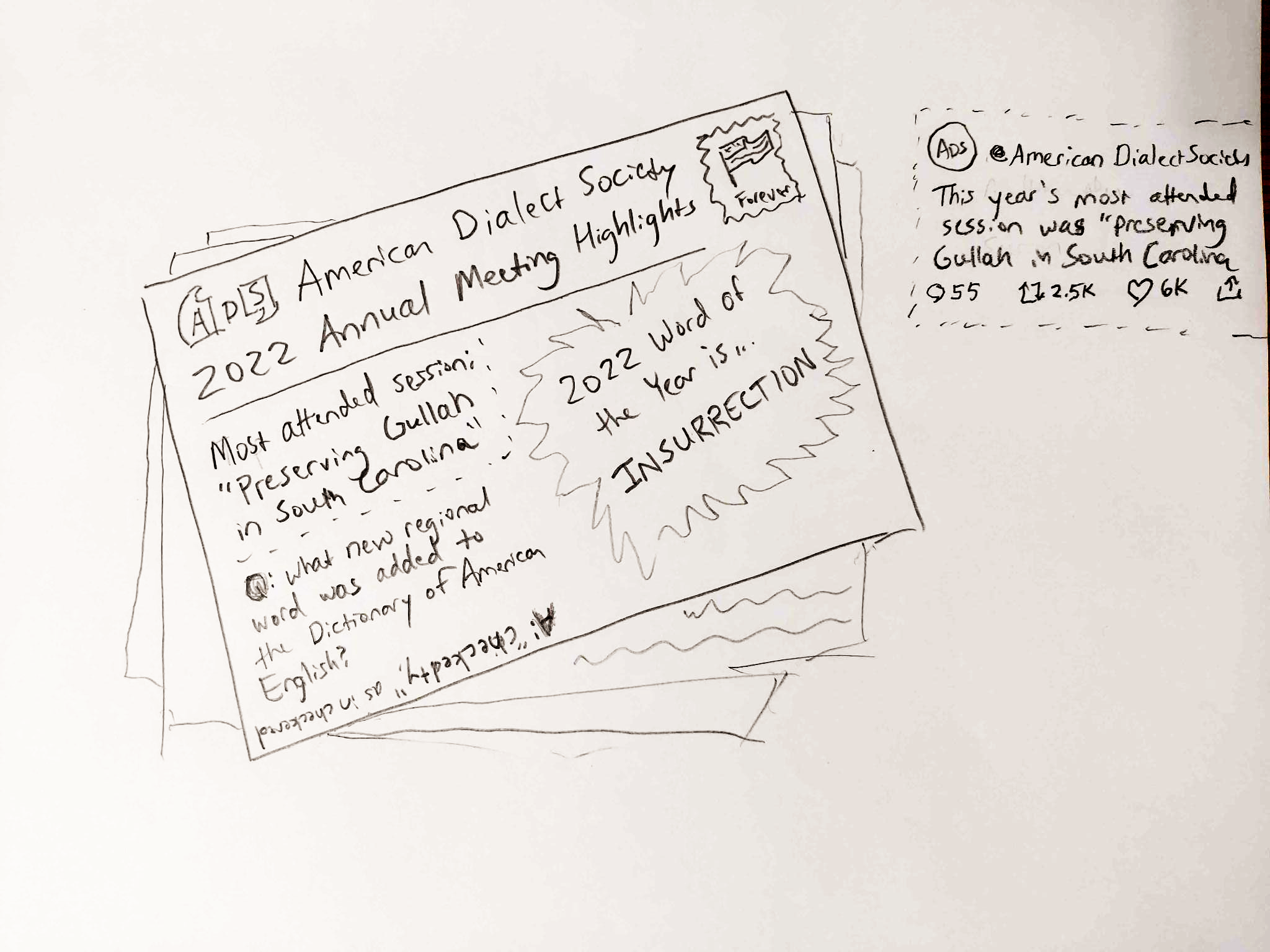

“Wow” Postcards

In this concept, a wrap-up session is held at the end of the conference where attendees can debrief, discuss, and share their excitement and takeaways. Those takeaways are then translated into physical mail or social media posts to promote the conference and particular sessions within it.

We received feedback that the wrap-up sessions themselves might be the biggest value-add, and most interviewees had viscerally negative reactions to the idea of mailing a postcard. They said it was logistically difficult and a waste of postage and printing, with the exception of one executive director who said the idea was “fun,” “nostalgic,” and “enchanting.” In addition, some societies already make announcements after conferences about highlights, such as the names of award winners. However, there were questions about the value of this type of communication, especially in the disciplines and conferences where session recordings aren’t made available after the fact. Absent a way for members to assess conference content, the value of sharing highlights seemed minimal. While this idea generated a good amount of excitement during the brainstorming session, it did not hold up to further scrutiny.

The next two concepts, which showed the most promise, were further refined throughout the next several months. They were tested in September 2022, expanded and refined, and then tested again with different society staff in October 2022.

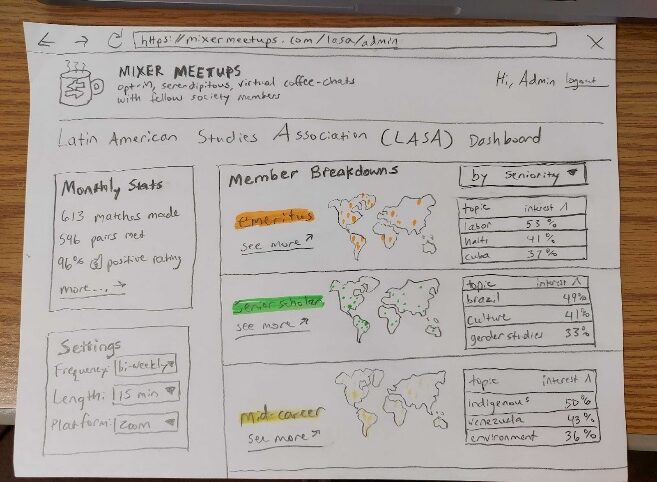

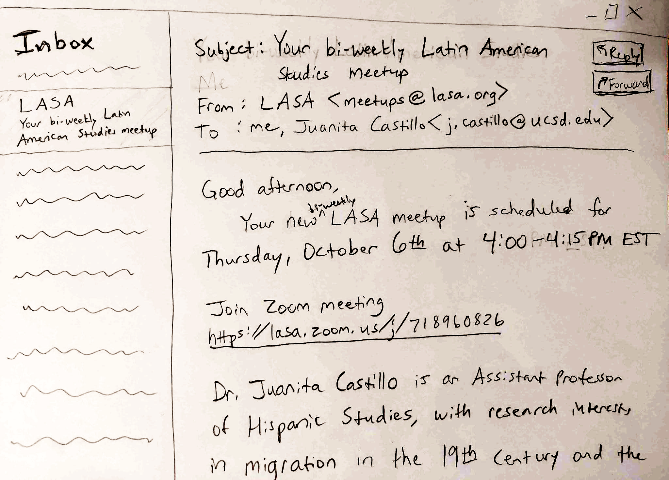

Bi-Weekly Random Chats (like Donut) aka Mixer Meetup aka Mixer.ly

In this concept, society members opt in to semi-randomly paired coffee chats. These chats are intended to augment or replace the serendipitous networking opportunities that occur at in-person conferences.

This idea inspired discussion, delight, and further ideation from some interviewees. These types of random matches may be more or less helpful to a scholar depending on career trajectory and progress. For instance, a well-networked senior scholar who already mentors their fair share of junior scholars might have little use for this service. In addition to helping societies fulfill their constituents’ networking needs, societies could potentially also use random chats to gather data about scholars’ interests and involvement. Some interviewees questioned whether this should go broader (e.g. cross-society) or narrower (e.g. subdisciplines).

There were also some concerns about safety and conduct, for which the society might be liable. Finally, there are tools with similar functionality, such as the Donut app within Slack, meaning that it is not a “defensible” idea in the startup sense. As one person put it, LinkedIn could add this next week.

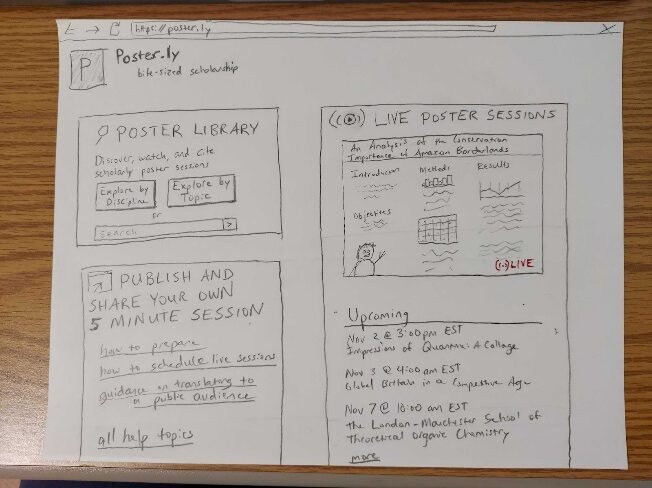

Poster.ly aka Academic Twitch

In this concept for “bite-sized scholarship,” five-minute poster sessions or lightning talks are presented live as well as hosted for later viewing. We envisioned a search function for past posters, a help section on how to best prepare and present this type of talk, a live feed on the homepage, and a list of upcoming live sessions. If someone chooses to join a live poster session, they see the presenter overlaid on the presentation/poster, as well as an interactive chat.

Participants had different opinions as to whether this should be segregated by society, perhaps white-labeled, or a single cross-society, cross-disciplinary platform.

For some societies and disciplines, this idea was generally exciting, though they were still concerned about moderation of live sessions. The societies who were interested in the idea also remarked it could be helpful in keeping scholars engaged year round or alleviating issues with overflowing poster halls in the larger societies.

However, in disciplines where a) posters or short-form presentations aren’t valued or b) posters and short-form presentations are HIGHLY valued and secretive, Poster.ly was not appealing. The latter group had concerns about intellectual property theft or the desire not to preserve poster sessions where incomplete work that isn’t finalized may be presented.

Endnotes

- Nicholas Rowe, “Conferences Mean High Times but Low Returns,” Times Higher Education, 12 April 2018, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/conferences-mean-high-times-low-returns. ↑

- Notable exceptions to this are societies such as the American Physical Society, the American Chemical Association, and the American Mathematical Society that continue to play active roles as independent publishers: market changes in the academic publishing landscape have led many societies to contract out much of this work. See Vincent Lariviere, Stefanie Haustein, and Philippe Mongeon, “The Oligopoly of Academic Publishers in the Digital Era,” PLoS ONE 10, no. 6 (June 2015) https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0127502; David Crotty, “Market Consolidation and the Demise of the Independently Publishing Research Society,” The Scholarly Kitchen, 14 December 2021, https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2021/12/14/market-consolidation-and-the-demise-of-the-independently-publishing-research-society/. ↑

- For an overview of conference costs and business models, see Mark Carden, “What Should a Conference Cost?” The Scholarly Kitchen, 11 February 2021, https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2021/02/11/guest-post-what-should-a-conference-cost/. ↑

- Colleen Flaherty, “The Great Conference Con?” Inside Higher Ed, 24 July 2017, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/07/25/article-sparks-new-round-criticism-costs-associated-academic-conferences; Julian Kircherr and Asit Biswas, “Expensive Academic Conferences Give Us Old ideas and No New Faces,” The Guardian, 30 August 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/2017/aug/30/expensive-academic-conferences-give-us-old-ideas-and-no-new-faces; Sarvenaz Sarabipour et al., “Changing Scientific Meetings for the Better,” Nature Human Behaviour 5, no. 3 (March 2021): 296–300, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01067-y; Catherine Oliver and Amelia Morris, “Resisting the ‘Academic Circle Jerk’: Precarity and Friendship at Academic Conferences in UK Higher Education,” British Journal of Sociology of Education 43, no. 4 (June 2022): 603-622, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01425692.2022.2042193. ↑

- Sara Custer, “Twitter Responses Show Sexual Harassment Is Rife at Academic Conferences,” Times Higher Education, 21 May 2019, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/twitter-responses-show-sexual-harassment-rife-academic-conferences; Race MoChridhe, “Academic Travel Culture Is Not Only Bad for the Planet, It Is Also Bad for the Diversity and Equity of Research,” London School of Economics Blog, 19 March 2019, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2019/03/19/academic-travel-culture-it-is-not-only-bad-for-the-planet-it-also-bad-for-the-diversity-and-equity-of-research/; https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-01467-2; Nina M. Flores, “Harassment at Conferences: Will #MeToo Momentum Translate to Real Change?” Gender and Education 32, no. 1 (November 2019): 137-144, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09540253.2019.1633462?journalCode=cgee20; Anonymous, “As a Young Academic, I Was Repeatedly Sexually Harassed at Conferences,” The Guardian, 1 December 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/2017/dec/01/as-a-young-academic-i-was-repeatedly-sexually-harassed-at-conferences; Kyra Leigh Sutton, “Conferencing While Black Is Exhausting,” Inside Higher Ed, 16 June 2022, https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2022/06/17/challenges-attending-conferences-black-academics-opinion; Scott Jaschik, “Dark Side of a Scholarly Meeting,” Inside Higher Ed, 24 June 2018, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/06/25/twitter-thread-reveals-how-woman-academic-conference-was-nearly-sexually-assaulted; Ebony O. McGee and Lasana Kazembe, “Entertainers or Education Researchers? The Challenges Associated with Presenting While Black,” Race Ethnicity and Education 19, no. 1 (2016) 96-120, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13613324.2015.1069263#preview; Lewis A. Wheaton, “Many Neuroscience Conferences Still Have No Black Speakers,” Scientific American, 10 November 2021, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/many-neuroscience-conferences-still-have-no-black-speakers/. ↑