Supporting Research in Languages and Literature

Foreword

We at the Modern Language Association are proud to have sponsored the research for Ithaka S+R’s report, Supporting Research in Languages and Literature. Research tools have shifted tremendously in recent years, and this report gives college and university libraries, faculty members, and publishers a comprehensive look at the research processes used by today’s faculty members. The in-depth interviews and incisive analysis in this report paint a picture not only of how scholars pursue research in the humanities but also of the ways research tools and processes need to change to meet new conditions.

As the publishers of the MLA International Bibliography, we naturally were interested in scholars’ discovery processes and in finding out ways we could meet the changing needs in the profession. We were delighted, however, at how much more we learned from the research on this project. What the report presents is a picture of the entire research workflow for a range of different kinds of scholars, with special attention to considerations of diversity and equity. How does the availability of certain kinds of tools affect choice of topic? Are language and literature faculty members working collaboratively? How much are they pursuing topics in public humanities versus traditional disciplinary research topics? The report draws on the perspectives of researchers from different types of institutions, from regional public colleges to private doctoral universities.

Perhaps the most exciting result of this project for us is the series of recommendations at the end of the report. Rather than a frozen-in-amber summary of the state of the matter at the moment the interviews were conducted, the report is a forward-looking document, using current findings to indicate future directions and to point to the kinds of changes we in scholarly publishing and research libraries need to make to give the scholars of today and tomorrow the support they will need to move the humanities ahead.

I thank Ithaka S+R, and especially Danielle Cooper, Cate Mahoney, and Rebecca Springer, for working with us on this project and for their support of quality research in the humanities. Thank you too to the research teams that conducted these interviews. We’re especially grateful to the MLA members who gave their time as project advisors: Howard Rambsy II, Roopika Risam, Patricia Simpson, Dana Williams, and Arielle Zibrak, as well as to the MLA staff members who worked so hard on the project. Humanities research is essential for understanding the world in which we live, in its political, environmental, and even medical complexities. Work such as this report gives us the context we need to support that research both now and in the future.

Paula Krebs, Executive Director, Modern Language Association of America

Executive Summary

Ithaka S+R’s Research Support Services program investigates how the research support needs of scholars vary by discipline. From 2018 to early 2020, Ithaka S+R examined the changing research methods and practices of language and literature scholars in the United States with the goal of identifying services to better support them. The goal of this report is to provide actionable findings for the organizations, institutions, and professionals who support the research processes of language and literature scholars.

This project was undertaken collaboratively with research teams at fourteen US academic libraries.[1] We are delighted to have the Modern Language Association (MLA) as project partner and sponsor for the project, and Paula Krebs, MLA executive director, as project advisor. MLA also furnished a fifteenth research team which focused on scholars at regional comprehensive colleges and universities in the United States. The project also relied on scholars who are leaders in the field to engage in an advisory capacity. We thank Howard Rambsy II (Southern Illinois University Edwardsville), Roopika Risam (Salem State University), Patricia Simpson (University of Nebraska-Lincoln), Dana Williams (Howard University) and Arielle Zibrak (University of Wyoming) for their thoughtful contributions.

The field of languages and literatures embraces a broad range of interdisciplinary influences, languages and regions studied, and “texts”—in forms ranging from books to newspapers to video games—studied. Yet it has a distinctive flavor among other humanities disciplines. Language and literature scholars share a tendency to center research on core texts, and the field is deeply invested in the physicality of texts both as research tools and as objects of research. These unique qualities inform the workflows of language and literature scholars in navigating archives, identifying relevant scholarly literature, using algorithm-powered discovery tools, and engaging with colleagues. Scholars’ practices are also significantly shaped by the forms research outputs take. As in other fields, the monograph and peer-reviewed article remain the paramount modes of scholarly communication, shored up by tenure and promotion incentives that favor traditional formats. Digital humanities and public humanities approaches remain on the margins—for now.

This report highlights opportunities for those invested in fostering the language and literature research endeavor—university administrators, librarians and archivists, publishers, research tool providers, and scholars themselves—to support the changing research practices of language and literature scholars. We offer recommendations for providing training in foundational research skills, accelerating the discovery of archival and scholarly resources, helping scholars connect with peers, and paving the way for new research directions.

The research that underlies this report was conducted prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we believe our findings resonate now more than ever. Perhaps no field of scholarship is as attuned to the interpretive and expressive power of context—the settings, modes, and mindsets in which we interact with texts—as the field of languages and literature. COVID-19 has set the context of academic research in flux. In describing the enduring importance of physical texts and the emergence of digital scholarship horizons, this report sheds light on the pandemic’s disruption of “research as usual” and points toward future possibilities.

Introduction

Through its Research Support Services program, Ithaka S+R conducts in-depth qualitative analysis of the research practices and associated support needs of scholars by discipline. Our previous projects in the program studied scholars in history, chemistry, art history, religious studies, Asian studies, agriculture, public health, civil and environmental engineering, and Indigenous studies.[2] A scholar-centered approach to understanding research in higher education is crucial to developing information services and spaces. By studying different disciplines, we gain a better understanding of how research activity functions across the academy.

The establishment of the Modern Language Association in 1883 marked the emergence of the academic study of modern languages (languages other than classical Greek and Latin) and literature at American universities.[3] Departments of English literature and modern languages expanded with rising university enrolment after the second world war.[4] During that time, the discipline shifted its focus away from philology and the historical progression of the literary canon, and a distinction emerged between literary criticism—an attempt to assess the merits of works of literature—and literary studies, an academic investigation of literature as a way of understanding its cultural context.[5] The latter orientation enabled the discipline to adopt new interpretive lenses, including feminist, Marxist, postcolonial, and queer theories, and to acknowledge a greater diversity of literary voices. Language and literature scholars have also embraced an increasingly global outlook, with growing numbers of scholars focusing their research outside Europe and North America.

Today, the discipline of languages and literature is at a crossroads. Undergraduate enrollments in English and modern languages have been declining,[6] and recent PhDs’ chances of attaining a tenure-track job were low even before the COVID-19 pandemic spurred widespread hiring freezes.[7] At the same time, digital methodologies, nontraditional forms of scholarly communication, and alternative career paths present exciting new opportunities to engage wider audiences.[8] The pandemic has also prompted renewed calls for humanistic scholars to contribute to societal dialogues on pressing subjects including collective responsibility, scientific authority, and inequality, including through translational or “public humanities” scholarship.[9]

It is important to understand the support needs of language and literature scholars at this critical juncture. This report explores their information activities over the entirety of the research lifecycle—from identifying a research topic to publicizing findings—as well as their perceptions of the key issues facing the discipline and what those issues mean for the evolution of language and literature research. We share our findings and recommendations in order to highlight opportunities for a variety of stakeholders to better support their scholarship.

Methods

This project is part of Ithaka S+R’s ongoing program to conduct research on scholarly information practices by discipline through collaboration with higher education institutions.[10] Conversations with leaders in the field informed the decision to frame the project around “languages and literature,” as well as the key issues the research would address. We thank Paula Krebs (MLA), Howard Ramsby (Southern Illinois University Edwardsville), Roopika Risam (Salem State University), Patricia Simpson (University of Nebraska-Lincoln), Dana Williams (Howard University) and Arielle Zibrak (University of Wyoming) for their thoughtful contributions.

Participation in the project was open to any academic libraries of US higher education institutions able to conform to the project specifications, such as timeline and research capacity. Fourteen institutions, listed in Appendix 1, participated in the project. The Modern Language Association (MLA) fielded an additional research team, which conducted telephone interviews with scholars at a variety of institutions across the United States and US territories. Reflecting a desire to include the perspectives of scholars at a variety of types of institutions, the MLA team recruited only scholars from regional comprehensive colleges and universities, including several minority serving institutions.[11] Further research is needed to illuminate how researchers’ needs vary by institution type.

Each research team consisted of one to four members who, following a training workshop designed and led by Danielle Cooper, collected the qualitative data that Ithaka S+R analyzed for this report. The research teams at the participating institutions primarily comprised subject librarians but also included participants in other roles, such as assessment librarians. Each team conducted research with approximately fifteen language and literature scholars at their institution through semi-structured interviews that followed the arc of the research process (see Appendix 2 for the interview guide).

Teams developed their own analysis from the data they collected at their respective institutions with the option of either creating an internal whitepaper or a publicly available local report. The publicly available local reports, which provide a complement to this capstone report, are listed and linked in Appendix 1. In what follows, insights from and resonances with local reports are indicated in footnotes.

Ithaka S+R collected anonymized transcripts from the 192 interviews conducted across the participating institutions. We selected 40 of these transcripts as a representative sample based on the research subfields delineated below, academic title (lecturer, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), and institution. Figure 1 summarizes this sample. This study does not purport be statistically representative nor are the recommendations meant to be prescriptive; rather, the report and its recommendations are intended to be suggestive of areas for further investigation. The sampled transcripts were analyzed through a grounded approach to coding utilizing NVivo software, with additional keyword-based analysis conducted across the entire body of transcripts. The interviewees remain unidentified in this report to protect anonymity. We thank the interviewees for their participation.

Table 1. Representation of Professional Rank and Research Area among Interviewees

| Rank | Percent of Interviewees |

|---|---|

| Lecturer/Teaching/Clinical | 2% |

| Assistant Professor | 20% |

| Associate Professor | 35% |

| Professor | 43% |

| Total | 100% |

| Research Area | Percent of Interviewees |

|---|---|

| Area Studies | 76% |

| Cultural Studies | 19% |

| Writing Studies | 5% |

| Total | 100% |

Defining the Language and Literature Scholar

This report focuses on the research practices and needs of language and literature scholars at higher education institutions. Because the aim of this project was to illuminate research practices, we hold teaching practices and pedagogical research out of scope and “scholars” as individuals who are employed by their institutions with research as a significant component of their job responsibilities, as opposed to those who exclusively teach. This means that language instruction is excluded from the scope of this project, even though it is an important function of language and literature departments. Additionally, graduate students were not included in this study.

The field of language and literature is characterized by its breadth and interdisciplinarity, with scholars in English and modern language departments borrowing research methodologies from history, musicology, art history, film and theater studies, cultural studies, philosophy, anthropology, and linguistics. Language and literature researchers may define their purview of study according to any number of categories, including country or region (e.g. Italy, Latin America, the postcolonial world); time period; methodology (e.g. archival, ethnographic, cultural history); genre or media (e.g. novels, film/television, theater/performance, poetry, music, cultural productions, video games); specific languages or linguistic phenomena; specific authors; or themes (e.g. secularism, book burning, kinship). An additional, overlapping category with which some language and literature scholars identify is the “digital humanities,” which refers to scholarship characterized by technology-enabled methods of research, analysis and communication.

For the purposes of scoping this project, we grouped the scholarship of languages and literature into three broad categories:

Area studies. The study of literature and other cultural products in a particular language (e.g. English, Chinese) or originating in a particular area of the world (e.g. Latin America), including research that crosses multiple languages or geographic areas.

Cultural studies. The study of cultures in relation to systems of power, informed by critical theory (e.g. African American studies, gender studies).

Writing studies. The study of the production, consumption, and circulation of writing (e.g. rhetoric, genre studies, publishing studies).

However, in practice, it is often difficult to identify a language and literature scholar’s research with only one of these categories; scholars often define their work according to both geographical boundaries and theoretical orientations, for instance. In the analysis that follows, other, less formal distinctions—such as researchers who work in archives within versus outside the United States, or researchers who place greater or lesser prioritization on public engagement with their work—often take precedence.

Core Text, Physical Text

It is not a mere cliché to assert that the field of languages and literature is populated by scholars who love books. Even as research workflows become increasingly digitized, language and literature scholars still gravitate toward practices of scholarship that center the book as a physical object, whether annotating a text in the margins, browsing bookstore shelves, or studying the material culture of books. Zooming out from research processes to the scope of language and literature research itself, we find that scholars tend to build their research projects around one or more core text(s), broadly defined. The centrality of the physical book and the core text have important implications for how scholars discover and work with research materials.

Paratextuality and the Physical Book

Today, the research of language and literature scholars is largely conducted using digital tools, as will be discussed below. However, for language and literature scholars, the “book as object” remains extremely important. The French literary theorist Gérard Genette coined the term “paratext” to describe all the aspects of a book outside and surrounding the body text itself.[12] This report uses paratextuality as a way to understand language and literature scholars’ interest in the physicality and the physical contexts of literary texts, both as research tools and as objects of research.

Many language and literature scholars, regardless of career stage, place a high value on owning print copies of books.[13] This stems in part from simple affection for the physical object. “If there’s only one thing that I love to own, it’s a book,” explained one interviewee. Another motivation for owning books is the ability to annotate them extensively by hand—a byproduct, perhaps, of the discipline’s enduring orientation toward the close reading of core texts (see “Text-Centered Workflows” below). One scholar gave a hierarchy of formats for annotation: “I would rank owning the book first, digital access second, and then physical library copy third.” Interviewees described annotating by hand in books they own, using annotation software to mark up e-books (“in the way I used to do it on paper,” one scholar remarked), and taking notes separate from the text in annotation software for physical library copies. A smaller number of scholars prefer working with e-books and annotation software such as iAnnotate to using physical copies, presumably because this allows them to carry extensive digital “libraries” with them. Tablets are seen as preferable to laptops for reading and annotating digital copies of texts.

“If there’s one thing I love to own, it’s a book.”

Language and literature scholars accumulate their own personal “libraries” of print literary texts and scholarly literature by purchasing books online, subscribing to journals or magazines, and visiting bookstores and publishers’ booths at conferences.[14] Scholars also save money by looking for second-hand copies on Amazon or AbeBooks. Additionally, the opportunity to find hard-to-come-by texts published outside the United States is an incentive to research travel: interviewees waxed lyrical about browsing through family-owned bookstores in Iceland or librarie vendors in African markets. It is important to note, however, that the ability to experience such novelties requires research leave and access to travel funding, a luxury that many early career researchers and faculty members at less resourced institutions do not enjoy.

This notion of “browsing” through physical copies of texts—whether in bookstores, archives, or libraries—was mentioned repeatedly by interviewees.[15] Language and literature scholars relish what feels like serendipitous discovery. (Of course, the arrangement of books in these contexts is often highly intentional.[16]) “It’s still indispensable to go to the [library] stacks just to see the texts that are adjacent and have a moment where I encounter the book I didn’t even think to look for electronically,” one scholar explained. “I don’t want to be too tidy when I’m looking for unexpected connections.” Embracing the unexpected allows language and literature scholars to alight on unique research topics and novel perspectives. It is also a product of the discipline’s propensity to value interesting scholarly conversations over exhaustive coverage of the secondary literature (see “Engaging the Scholarly Community” below). In other words, language and literature scholars are not just searching for everything that may be relevant—they are searching for compelling dialogues among texts.

The influence of material culture studies within the discipline has also made the physicality of books—particularly historical books—a critical aspect of research.[17] For instance, one interviewee explained that when reading a particular eighteenth-century poet’s work in modern editions, “about 60 percent of the meaning behind and encoded in the poem is lost” if the format of the original printing is not also studied. The desire of many language and literature scholars to experience and examine objects in person resonates with the practices of art historians, although language and literature scholars are probably more amenable to working with digital surrogates overall.[18] While high-quality digitization or reproduction are considered acceptable substitutes—and often greatly facilitate access—for many scholars, the opportunity to “get into archives and just handle” materials is also important. Language and literature scholars’ uses of archives is discussed below in the “Working with Archives” section.

Text-Centered Workflows

Most research projects undertaken by language and literature scholars focus on a core text or corpus of texts, broadly defined. Under the influence of cultural studies, the very notion of what a “text” is has been expanded to include other types of cultural objects which carry meaning or discourse, from films and video games to architectural spaces and performances.[19] As one scholar put it, “anything’s a text for us to study now.” Interviewees described coming across promising “core texts” through a variety of avenues, including related earlier projects, the scholarly literature, archival research or conversations with archivists, interactions with colleagues, and even teaching experiences.[20]

After identifying the core text(s), the researcher typically searches for a unique angle—an aspect of the text or its context that has not been fleshed out in the scholarship. This search typically involves a combination of archival work and/or investigation of related texts with a review of the scholarly literature, as the researcher asks questions and follows hunches to decide whether they merit further study. One scholar put it succinctly: “we begin with what we know, and then we think, and then we go to the library to find things that we don’t know.” When identifying an angle, novelty is value: one scholar described searching exhaustively in libraries, bookstores, and the internet to verify the “newness” of an idea before proceeding to search for a theoretical angle in the scholarly literature.[21] Research then proceeds through iterative stages of reading and writing; as described in the “Research Outputs” section below, most projects culminate in one or more scholarly publications.

The discipline’s orientation toward centering research on core texts influences how scholars search for information.

The discipline’s orientation toward centering research on core texts influences how scholars search for information. They usually approach archives and libraries looking for materials related to a particular text or author. However, it is also important to note that not all research in the discipline conforms to this pattern. Although the core text—however defined—remains central to the workflows of language and literature scholars, interviewees also described defining research topics in relation to theory-driven questions or historical phenomena.[22] Scholars embarking on theory-oriented projects may scope their projects using the scholarly literature before proceeding to identify relevant texts to focus on, while more historical or anthropological projects often begin with wide-ranging archival research. “I would say that I tend to go to a library and work there for an extended period of time,” remarked one interviewee, “and there, through secondary bibliography or consultation with the curators, I find more texts to work on.” Language and literature scholars’ discovery practices are explored in greater depth in the next section.

Research Workflows

“Workflow” means the sequence by which scholars move through a research project, from start to finish.[23] Although the research practices of language and literature scholars vary according to methodological orientation, source type, output type, and personal preference, some important patterns can be discerned. This section discusses how language and literature scholars discover and access various types of information, the extent to which they consider and understand the discovery tools they use, and how they engage with colleagues throughout the research lifecycle.

Working with Archives

A majority of language and literature scholars interviewed for this project use archives or special collections material, or expect to do so for future projects. (In what follows, we use the term “archives” to refer to both archives and special collections departments.) Unsurprisingly, a number of interviewees reported that the increase in availability of archival materials online—either through institutional websites or through generalist repositories like HathiTrust—means they spend less time visiting archives than they did a decade or two ago. Like their colleagues in other humanities fields, language and literature scholars generally make use of digital surrogates whenever they are available “in order to save the cost of going and examining it, and the time.”[24] As discussed in the “Paratextuality and the Physical Book” section above, they may still make an effort to visit materials in person if there is “a really compelling reason to examine the material object.”

Language and literature scholars also spend considerable time in archives consulting materials that have not been digitized. Simply identifying potentially relevant items or collections can be challenging. Many scholars prioritize building working relationships with archivists, who can often suggest materials of interest that would not be apparent from searching catalogs or finding aids. A few interviewees reported that archivists had reached out to them following a visit to share additional relevant materials or to alert them to new acquisitions that had not yet been processed and cataloged: “You wouldn’t know about if you didn’t talk.”

Scholars prioritize building working relationships with archivists.

Other interviewees voiced frustration around communicating with archivists and navigating archival collections. The task of searching for relevant material is made more laborious for collections that have undergone minimal processing,[25] although interviewees were sympathetic to archives’ limited resources. One scholar discussed the archival trend toward “MPLP” (more product, less process) —organizing and listing materials in larger groups in order to make them available to researchers sooner.[26] “I’m not against that because I like to promote the idea of access,” they explained. “But the time that archivists are no longer taking to . . . give those item-level details is now switched back on the researchers.”

The access policies of specific archives, especially archives outside the United States, also arose as a pain point in scholars’ research workflows. Interviewees related stories of limited access to finding aids, intensive permissions processes, and bureaucratic headaches. At some archives, digital photography is not allowed, and scholars must take notes and transcribe documents by hand. A few interviewees spoke of more intangible barriers to using archives. “It’s really important to be able to convince [archivists] of the seriousness of your project and … of you as a person” in order to access materials, one explained. Another noted that researchers who are people of color may feel “a little bit out of place” in archives. “Archives tend to be spaces that you don’t see that many non-white people. It’s still a very exclusive space.”

Working with Scholarly Literature

Like their colleagues in other humanities fields, language and literature scholars rely on a mix of discovery tools to help them find relevant scholarly literature. They search using Google, Google Scholar, WorldCat, their library’s catalog, and the MLA Bibliography. Databases such as EBSCO, JSTOR, Project Muse, and ProQuest are also frequent starting points for research. Notably, although many language and literature scholars report using Google Scholar, that search engine is not as predominant in this field as it is in STEM disciplines.[27] One scholar commented that Google Scholar doesn’t have “a very good inventory of humanities research.” In addition to keyword searching, language and literature scholars also rely on algorithmically-generated recommendations available through Academia.edu and Amazon.[28] (Interviewees did not report using nonprofit academic networking sites like Humanities Commons for this purpose.) They also value the ability to search the full text of online resources, such as through Google Books. A few interviewees expressed a desire for improved optical character recognition (OCR) in digitized texts. Foreign language texts, especially texts written in languages which do not use the Roman alphabet, pose a particular challenge.[29]

A few interviewees described how liaison librarians who were familiar with their research project had proactively helped them identify useful resources.[30] These close working relationships, however, may be exceptional. A few other interviewees said they did not know whom they could contact for help at their libraries.[31] Many explained that they generally do not ask library staff for help in finding materials, either because they do not feel they need assistance or because they believe that their research is so specialized that a librarian would not be able to help them.[32]

Algorithm Agnostic

Public concern over the algorithmic bias of search engines is growing.[33] However, this public discourse has generally not included critiques of the algorithm-enabled ways in which academics discover scholarly literature and other research materials. Asked whether they understood how the search engines they use to conduct their research work, most interviewees responded with confusion. Many expressed that they were content with not being able to understand how search engines work as long as they could find what they need. [34] “I would say I don’t know how things work exactly, but I care less about that than the fact that I’m getting what I want,” one scholar explained. Others suggested that search algorithms could be improved to make keyword searching more effective: “I think sometimes algorithms don’t get it.”

“I would say I don’t know how search engines work exactly, but I care less about that than getting what I want.”

Many other interviewees, when asked to comment on how search engines work, said they had never thought about this issue with regards to their scholarship.[35] Interviewees did not express concerns that they were missing relevant content due to the algorithms used in digital discovery tools.[36] Several did express a vague sense that search engines like Google are “super opaque.” Nevertheless, the ease and effectiveness of Google and Google Scholar compared to other search tools means that scholars continue to utilize them despite their unease:

It places me at the mercy of a giant corporation. And so I wish I had more responsible tools. . . . I wish [the library’s discovery tool] was as good algorithmically as Google and was doing the same things, but Google has billions of dollars and we here at [our university] do not have billions of dollars.”

Finally, an additional concern raised by scholars was the Western bias of online databases, metadata, and digitized materials.[37]

Tools and Training

Like scholars in many other fields, language and literature scholars have personalized and idiosyncratic ways of organizing their research materials, notes, and writing. Most utilize a limited range of basic workflow tools. For instance, use of the citation management software Zotero—or, less frequently, EndNote or RefWorks—is relatively common. The organization of primary source material often poses the greatest challenge. Like many historians, some language and literature scholars take large numbers of photographs when they visit archive.[38] As one interviewee put it, when visiting an archive, “I just take photos of everything.” Interviewees reported they do not have a good way to organize, annotate, or label these photographs, and none mentioned Tropy, a tool designed for this purpose.[39] (This may be due to the fact that Tropy is only available for desktop computer use, whereas many scholars use their mobile phones to take photographs in the archive.) Language and literature scholars also store large quantities of primary source material—either copied and pasted from online archives, or transcribed themselves—in Microsoft Word or Google Docs files.

Like their colleagues in other humanistic disciplines, most language and literature scholars have not received formal training in searching for archival or scholarly materials or managing their research workflows.[40] In graduate school, “it was sort of like, ‘Well, if you have what it takes, you’ll be able to figure this out,’” one interviewee revealed. Language and literature scholars who have obtained tenure-track or tenured positions may be reticent to admit that they still need training in research skills. One scholar declared that faculty should “no longer need a workshop [on working with discovery tools], because hopefully by the time you become faculty you have learned all of that.”

In spite of their own graduate school experiences—or lack thereof—with research methods training, language and literature scholars believe that current graduate students would benefit from instruction in this area. Many language and literature scholars opined that bibliographic skills have eroded with the rise of “one box” search engines. They expressed a desire for students to “tame the library” —or to embrace the labor of searching across multiple platforms, databases, catalogs and collections, including by visiting libraries and archives physically. This desire seems motivated partially by the discipline’s orientation toward physical texts and browsing in person, and partially by concerns about information literacy and even work ethic. Some interviewees believe, rightly or wrongly, that students are reluctant to engage with research beyond the Google search box.

Engaging the Scholarly Community

Most research in languages and literature is conducted by a single researcher. “In the humanities, we tend to be more of a solo act,” one interviewee quipped. Language and literature scholars do receive significant help from librarians, archivists, publishers, editors, and occasionally students, but do not describe them as collaborators. That term is generally reserved for coauthors, as is true in other humanities as well as STEM fields.[41] “Every article that gets published has been worked on by me, by maybe four different reviewers, by three different editorial assistants, and a managing editor,” one scholar explained, “but that’s not collaboration.” True project collaboration and coauthorship are relatively rare, with the notable exception of digital humanities and public humanities projects, which are frequently collaborative. Specifically, language and literature scholars often seek out collaborators with stronger information technology skillsets when embarking on projects with a significant web development or quantitative analysis components. Finally, scholarly outputs other than traditional monographs and articles are more likely to be undertaken collaboratively; such projects described by interviewees included an anthology and a manuscript catalog.

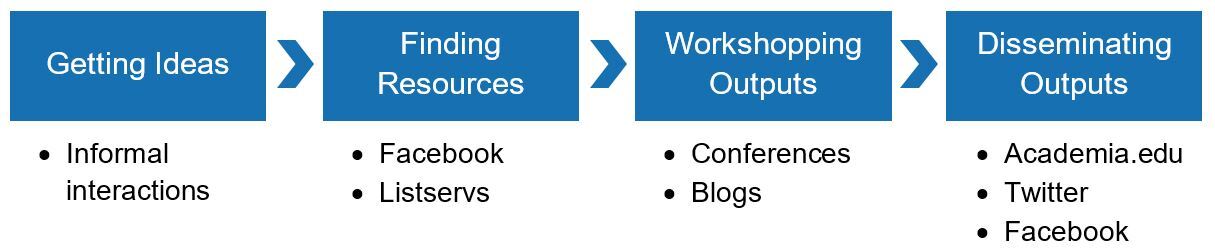

Although collaboration in the strict sense is relatively rare, language and literature scholars do benefit from engaging with their colleagues throughout the research process. The nature of that engagement, and the tools with which it is carried out, vary across the lifespan of a research project. Figure 1 simplifies the research process into four phases and lists some common ways scholars engage with their colleagues—other than through scholarly publications—at each phase.

Figure 1. Engaging Peers throughout the Scholarly Workflow

As discussed above, language and literature scholars often identify potential new research topics individually, by following leads or additional questions raised by previous research. However, a few interviewees described how research projects had arisen through extended conversations with their colleagues. “My collaborator and I went through graduate school together and we’ve always been thinking together about the history of our discipline and the way it’s narrated,” one scholar explained.

Engaging with colleagues becomes more important once the scholar begins to dig into a research project. In particular, language and literature scholars lean on their colleagues to help them find scholarly literature relevant to a particular topic or theoretical conversation. Although many scholars are wary using Facebook for professional (or even personal) networking, others reported posting on Facebook in order to pose research questions to trusted peers.[42] “I’ve had a couple experiences lately where a Facebook thread has produced a richer bibliography than I could produce on my own,” one scholar remarked. “Sometimes the searching that you do feels like it pales in comparison to that, in part because these are folks that I know and trust.” Scholars may start these questions by posting to their news feeds or within closed groups. Interviewees did not mention using the nonprofit networking site Humanities Commons for this purpose, even though it supports group discussion and collaborative bibliography functionalities.

“I’ve had a couple experiences lately where a Facebook thread has produced a richer bibliography than I could produce on my own.”

Many interviewees also use listservs in a similar way.[43] One scholar described posing a question to a listserv about films on a specific theme: “Immediately hundreds of people will chime in with obscure films that you haven’t heard of, in another language. Right? So, that’s . . . it’s a mind hive. It’s wonderful.” Listservs are often scoped around a language, a time period, or a thematic subfield; they are hosted by professional societies, publishers, and organizations like H-Net. One interviewee suggested that listservs are a convenient way to gather information because “when I open email it’s there. . . . I have a quick glance and I’m done with it.”

This emphasis on socially curated discovery is an important way in which language and literature scholars differ in their discovery practices from their colleagues in other disciplines. Scholars in other disciplines, such as history and chemistry,[44] commented on the difficulty of “keeping up” with the increasing volume of scholarly publication. While this anxiety was reported by some language and literature scholars as well, others described a more selective approach. “I don’t have time [to do a systematic literature review]—it’s not worth it for me to emphasize making sure that I’ve found everything that was written,” one scholar explained. Another commented, “You have to accept that you’re only going to see a small part of it, and [decide that] this is the area that strikes you as being the most promising.” The proliferation of scholarly outputs and discovery tools has made it more important for language and literature researchers to lean on their peers to decide “whose voice matters” within the scholarly conversation.[45]

The proliferation of scholarly outputs and discovery tools has made it more important for researchers to lean on their peers to decide “whose voice matters.”

As a research project approaches completion, a scholar in languages and literature will typically present initial findings at one or more conferences. These presentations can be a prestigious way to gain visibility for a project, but they function as a sort of first draft before writing a full-fledged article or book chapter for publication. Comments and discussion that arise are often incorporated into the final product. While interviewees also characterized conferences as opportunities to stay abreast of current developments in their subfields, this “workshopping” function appears to be the most important way in which language and literature scholars incorporate conference attendance into their research workflows. In addition to presenting works-in-progress at conferences, a few scholars also use personal blogs to air work that they are considering publishing as formal research projects within their scholarly communities. Unlike in some STEM disciplines, there is little culture of sharing and commenting on preprints of articles online in languages and literature.

The final stage in the research process, dissemination, is discussed at greater length in the “Research Outputs” section below. Here, we observe that scholars share their recent publications on several social media platforms. Although some scholars object to Academia.edu’s for-profit business model,[46] it is relatively common for language and literature scholars to maintain Academia.edu profiles as personal repositories of their work.[47] (ResearchGate, a similar website dominant in STEM fields, is not widely used by languages and literature scholars.[48]) A smaller number announce their recent publications via Twitter or their Facebook profile, and only a few mentioned ORCID in the context of linking all their research outputs online.

Language and literature scholars have a variety of motivations for publicizing their work online. One interviewee suggested that publishers encourage scholars to promote their work on social media because, according to the publishers, “it’s good for marketing.” Others attributed some importance to maintaining a “digital footprint” when applying for tenure-track jobs or, once hired, seeking tenure or promotion. “I do get a sense it matters in this fuzzier, social sense,” one explained, even if tenure and promotion committees do not evaluate candidates’ online presences formally. Another interviewee asserted that engagement online is most important for graduate students seeking academic jobs: “I think that’s actually essential to their livelihood in the profession.”

On the whole, language and literature scholars’ online engagement at the dissemination phase is more public and less community-driven than earlier in the research process. This is likely because incentives for social-professional engagement shift over the course of a research project. At earlier stages, scholars turn to relatively closed groups of peers, such as listservs, to ask questions and get advice. At the end of a research project, however, they tend to advertise their polished research outputs on more open and impersonal platforms such as Academia.edu and Twitter, using these platforms like a “beacon” to project their research out to wider academic audiences. Facebook, with its ability to publish content to an individual’s curated list of “friends” as well as to closed groups, straddles both functions.

The predominance of Facebook, Twitter, and Academia.edu in comparison with other online networking tools cannot be overestimated. These “big three,” alongside listservs, account for the vast majority of language and literature scholars’ online networking and discussion; both awareness and use tail off sharply outside this group. It is also important to note that many language and literature scholars do not engage professionally through social media or online networking sites at all, or only engage haphazardly. Like their colleagues in other disciplines,[49] interviewees for this project primarily pointed to the hazard of potentially wasting time as their reason for abstaining, with privacy and the perceived coarseness of online discourse secondary concerns.[50]

Research Outputs

When asked to describe the trajectory of their own research, language and literature scholars often narrated their work as a progression of projects leading to specific research outputs—traditional scholarly publications or, less commonly, digital humanities or public humanities projects.[51] In other words, language and literature scholars shape their research around anticipated outputs. This means that tenure and promotion incentives—which continue to favor a narrow range of traditional, peer-reviewed outputs—strongly influence what types of research scholars prioritize, and at what career stage they do so. It also means that fundamental questions remain about how to assess work produced within the digital humanities and public humanities movements.

Traditional Publications

As in other humanities disciplines, the primary modes of scholarly communication in languages and literature are monographs and peer-reviewed articles. Other traditional scholarly outputs, such as contributions to edited collections and critical editions, are also important.[52] There is a general consensus that languages and literature remains a “book field,” meaning that monographs are generally perceived to be the most significant and desirable publications.[53]

Like their colleagues in other disciplines, language and literature scholars decide where to publish books and articles based on subject fit and the perceived prestige of the press or journal.[54] This sense of prestige is understood implicitly within the scholarly community; quantitative measures popular in STEM fields, such as the journal “impact factors,”[55] are not important within languages and literature departments, despite moves by some university administrators to impose them. In general, language and literature scholars do not prioritize publishing in open access journals and are reluctant to pay article processing charges (APCs) to make their articles in hybrid journals open access. A few subfields, such as video game studies and digital humanities, have many open access journals and may represent exceptions to this trend.

Numerous interviewees expressed positive sentiments around the idea of their research being openly available, although they often conflated “open access”—free access to published, peer-reviewed articles—with other forms of online dissemination, such as digital archives and Academia.edu. However, these interviewees usually did not report having taken concrete actions to make their research open access. The pressure to publish in prestige journals—which are usually not open access—and the cost of article processing charges[56] contravenes any desire to make their work open.[57] As one unusually well-informed interviewee explained, “I would like [my work] to be copyrighted under a Creative Commons [open access copyright license] and I have absolutely no way of doing that because of the tenure system. . . . After I get tenure I’ll start to try to push that forward.” This resonates with findings from the Ithaka S+R US Faculty Survey 2018, which showed that younger faculty members across disciplines place less of a priority on publishing in open access journals than older faculty members.[58]

The continuing supremacy of the monograph within the field of languages and literature may also contribute to scholars’ ambivalence toward open access publishing, since the open access movement broadly focuses on journal articles. Although some publishers are experimenting with open access monographs—at least one interviewee reported having published a book both in print and in a free online version—this was not a priority for the scholars interviewed for this project.

Only a few interviewees reported that they had uploaded preprints of their articles to their campus repositories. Many scholars simply do not understand that they are able to do this or why they should. Others are confused about whether and how the copyright terms of their own work allow them to share it on platforms outside the publisher’s website.[59] Several interviewees reported that they share PDFs of their articles on Academia.edu, Facebook groups, or, less commonly, their personal websites; only some of these scholars mentioned paying attention to the copyright status of their work when doing so.

Digital Humanities

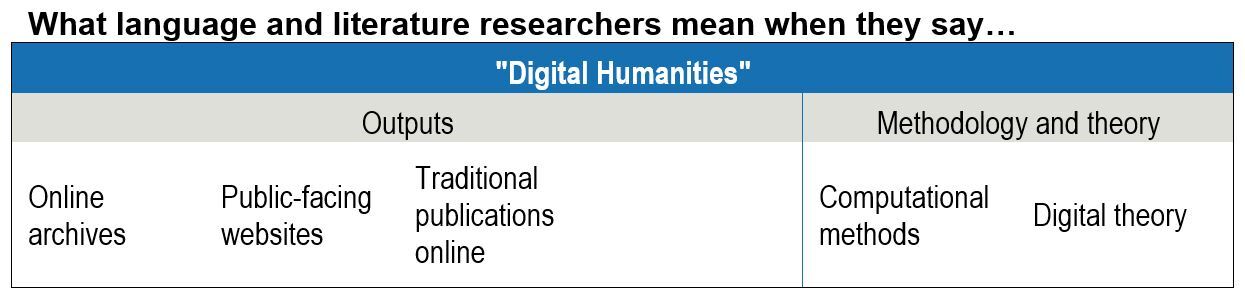

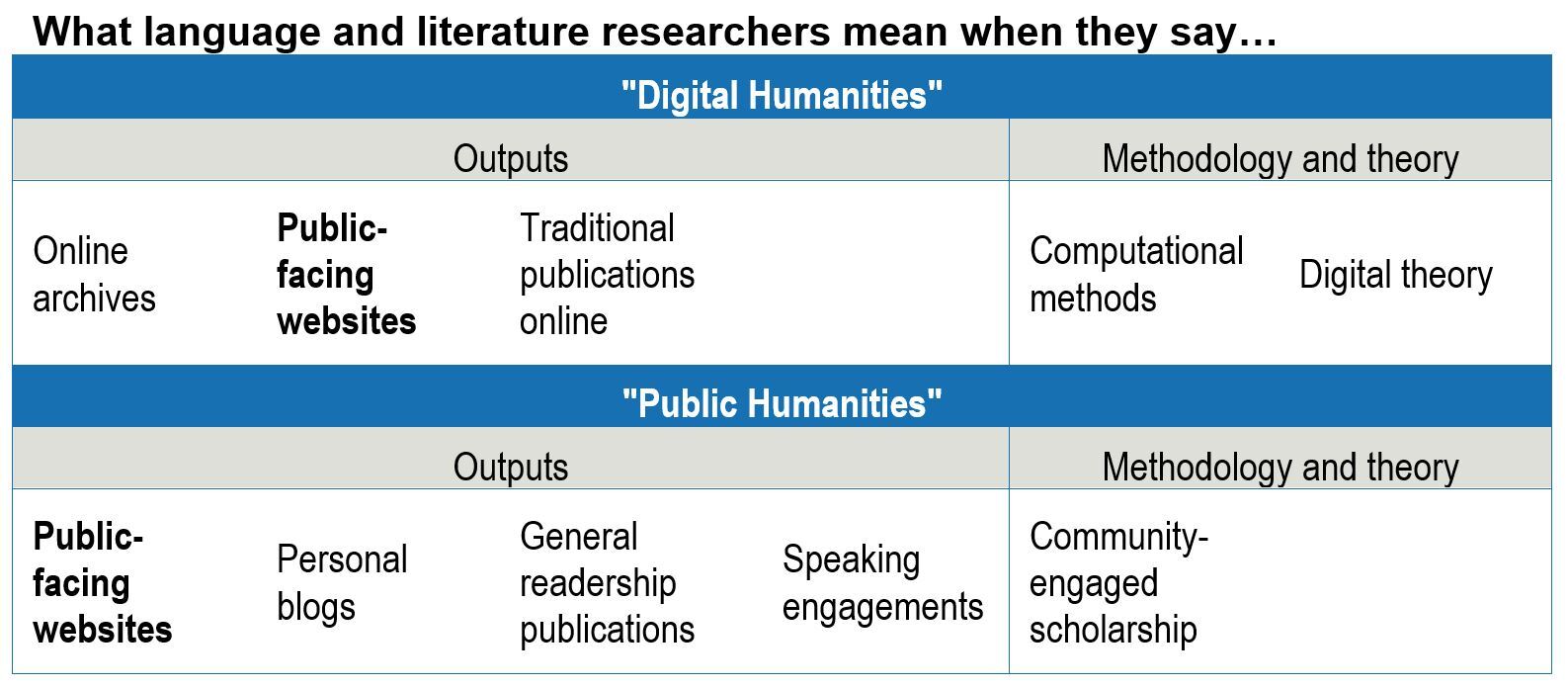

Although only a handful of interviewees for the project were actively engaged in digital humanities projects or were self-described digital humanists, many weighed in on the role of the digital humanities in the discipline of languages and literature. As discussed below, some language and literature scholars use the term “digital humanities” to refer to any research project which results in digital outputs, whereas others reserve the phrase for projects involving computational methodologies and digital theories. In this report, we discuss digital humanities as part of the “Research Outputs” section because the former interpretation was significantly more common among language and literature scholars interviewed.

Digital humanities is now several decades old, yet confusion about how to define the field still abounds. Many scholars associate the digital humanities with particular ways of disseminating scholarship or making primary sources available online. Numerous interviewees used “digital humanities” as a shorthand for digital archives and exhibitions, while others spoke of public-facing websites that make primary sources available in translation or allow users to explore interactive maps. In a few extreme cases, interviewees appeared to conflate digital humanities with open access, the online publication of traditional journals, or the evaluation of scholarship using quantitative indicators such as the Journal Impact Factor. Still other interviewees reserved the term “digital humanities” for projects employing data science methodologies, such as text mining.[60] And only a few identified the digital humanities with a theoretical orientation. “I have an interest in the digital self, and in performances and displays of the digital self,” mused one scholar. “I think that the way that my work ties into the digital humanities is that I don’t make a distinction between an analog or a digital body.”

This ambiguity appears to have significant implications for how language and literature scholars perceive and evaluate digital humanities research.[61] Several interviewees drew a distinction between digital humanities projects that involved, in their view, the less intellectually demanding work of making sources available online, and those that used digital methods to approach a more traditional research question. Said one scholar, “Digital humanities depends, really, on what we mean by it. If it’s just the making available of texts online, that’s not . . . a research accomplishment, per se.” Another interviewee even expressed reservations about the rigor of their own digital project:

I am currently engaged in a project that some people might classify as digital humanities, although I don’t think it is digital humanities, honestly. I sort of agree that it shouldn’t count for tenure. I don’t feel like this is unfair, because ultimately the part of the project that is real rigorous intellectual work is still the old fashioned article writing type.

Although digital humanities projects are proliferating, their place within the discipline remains undetermined. “In conferences there are lots of digital humanities people presenting. I can’t really assess whether they’re all good,” said one scholar. Many scholars remain committed to the idea that the traditional peer review process serves an important “gatekeeping” function for serious scholarly work. As a result, tenure and processes generally do not reward digital humanities projects.[62] “We see either graduate students or . . . tenured faculty branching into fairly deep digital projects, but not people who are right up against tenure track,” one scholar explained. Digital humanities proponents are frustrated by the slow pace of progress: “It’s starting to become silly for us not to know how to deal with” evaluating digital humanities projects for tenure and evaluation, one interviewee lamented.

“We see either graduate students or tenured faculty branching into fairly deep digital projects, but not people who are right up against the tenure track.”

Overall, the prevailing attitude toward the digital humanities of scholars interviewed for this project was one of curiosity—from a safe distance. Most interviewees who were prompted to speak about the digital humanities either pivoted to mention the work of a colleague or graduate student they knew, or mused that they had thought about embarking on a digital humanities project, but had never actually done so. A few said that digital humanities methods were not relevant to or appropriate for their research. However, many interviewees who were not themselves engaged in digital humanities still raised evaluation of digital projects as an unsolved issue in the tenure and evaluation process, suggesting that awareness of the uncertain status of the digital humanities within the field is high.

Finally, although ambivalence predominates, a few scholars expressed negative attitudes toward the digital humanities. One interviewee criticized “the kind of claims that are made for the digital humanities in terms of their ability to read through reams of data and produce insights. . . . I haven’t seen one article that has been convincing.” Another admitted that they don’t “see the point” of a colleague’s computational research, since “you could have come up with those generalizations without knowing the data.” A common thread in such critiques is the perception that the digital humanities privileges tools and methods which ultimately distract from the “real” work of the discipline. “I could collect so-called data,” said one interviewee. “It’s still a question of coming up with . . . the right words, asking the right questions . . . so what difference does it make whether it’s in an electronic format or a print format?”

Public Humanities

The field of language and literature is also coming to grips with another nontraditional research orientation: public humanities.[63] Like “digital humanities,” “public humanities” is a loose term denoting a variety of theoretical and methodological research approaches as well as forms of research output. At a basic level, public humanities aims to engage people who are not academics with humanistic research; it is an umbrella term that connects a range of disciplinary approaches to this engagement. Historians share a long tradition of reaching out to wider audiences through the practice of “public history,” with a strong bent toward illuminating cultural heritage artifacts and sites.[64] Some religious studies scholars’ research outputs are shaped by both scholarship and faith-based practice.[65] And social scientists have developed “participatory research” methodologies, which aim shift the locus of power from the scholar to the community with which they are engaging throughout the research process.[66] The language and literature scholars interviewed for this project usually responded to questions about “public humanities” by describing work falling into one of three broad categories: creating public-facing online research outputs such as websites; taking on the role of a “public intellectual”; and conducting community-engaged research.

When asked whether they had an interest in public humanities, many interviewees focused on research dissemination, discussing their willingness—or unwillingness—to create nontraditional, online outputs such as project websites. For example, one scholar discussed a public-facing website that translates Italian-language primary sources into English. In this way, language and literature scholars’ conceptions of public humanities and digital humanities research intersect. Most interviewees who spoke about public humanities in relation to digital outputs did not articulate a vision for how they would measure or promote public engagement with these outputs, other than making them available. It is also important to note that language and literature scholars generally do not view open access publishing as a proxy for public engagement; there is an implicit sense that traditional scholarly research outputs are inappropriate for wider audiences.

Other language and literature scholars implicitly equate public humanities work with taking on the role of a “public intellectual” (although one interviewee balked at that term, citing its origins in the work of Lionel Trilling). This role includes activities such as writing magazine article and op-ed columns, giving public talks, and appearing as a “talking head” in documentary films. The London Review of Books, New York Review of Books, and Los Angeles Review of Books were frequently cited venues for this type of engagement. It also includes publishing books destined for mass-market readerships. One interviewee characterized the role of a public intellectual as an ambition that scholars must choose whether to pursue: “These are people who will kind of want to self-promote themselves, right? Or they want to be on CNN or NPR. And, if that’s what you aspire to, then wonderful. But if not, most people are probably not going to come across your website.”

Finally, a few scholars associated public humanities with the growing movement of community-engaged scholarship.[67] Scholars practicing these methods strive not to simply conduct research about communities, but to conduct research with them and for their benefit. For one interviewee, this meant purchasing extra copies of their own published scholarship, giving them to the communities with which they worked when conducting research, and asking for feedback. “I have a whole community of friends, young scholars and also community activists,” this interviewee explained. “I believe that I’m a scholar and an advocate for social justice.” This resonates with the practices of Indigenous Studies scholars, who often seek input on draft publications from the Indigenous communities with which their research engaged.[68] Another observed that the “push toward engaged scholarship” has engendered an interest in humanistic fieldwork, especially among younger scholars. “It’s humanities research that involves the lived experience of people who are the objects of study,” they explained. “Certainly, we have a lot of grad students who are interested in that kind of work.”

“I believe that I’m a scholar and an advocate for social justice.”

Scholars’ expressed motivations for engaging in public humanities work often rested on convictions about the inherent value of language and literature research in public discourse—and on a sense of urgency in making that value known. Some spoke of an “obligation,” others of wanting to do work that is “satisfying” and “rewarding.” “We should be able to get people interested in literature, to show them what’s in it for them,” one interviewee stated. Another mused, “I think the university and the humanities departments have been grappling with their relevance.” Simply achieving a larger readership is a motivation sufficient for some scholars to want to write for more general audiences: “I don’t think we entered the field to speak to ten people.”[69]

However, even some interviewees who expressed positive feelings about engaging the broader public in humanities research sounded notes of caution. Several expressed fears of research being oversimplified or vulgarized. “It doesn’t mean that we should turn ourselves into entertainers,” one said. Another scholar, describing the opportunity to write a “popular history” book, added the caveat that such work should not be “trashy or anything.” The perception that “the bestseller is not academically strong” has important implications for how scholars choose to allocate their time. Like digital humanities projects, public humanities outputs are significantly less valuable for tenure and review evaluations than traditional, peer-reviewed publications.[70] “I’d love to have readers for my work whenever I can find them,” one interviewee explained. “The problem is you don’t know that your institution is going to care about that kind of stuff.” A partial exception to this rule is that some institutions reward scholars for securing research grants, including grants to fund public humanities work.

“It doesn’t mean we should turn ourselves into entertainers.”

As a result of this ambiguity, significant engagement in public humanities work among language and literature scholars remains relatively rare. Many respondents indicated that they would like to write public-facing outputs “in theory,” but cited time constraints as reasons for not doing so. A few expressed hesitation because they felt they lacked the skills needed to communicate in public forums. One scholar said they would like training in “how to write a sexy blog post about my research,” while another simply said, “I’m a little too shy.” In the end, language and literature scholars are simply not incentivized to overcome these barriers. “There are moments where I wonder, do I need to get on that bandwagon or not?” one interviewee explained. “And then in the end I’m reminded, OK, I think I have my ducks in a row for what I need for tenure and that’s fine.”

Conclusion

Although language and literature scholars share many research practices and challenges with their colleagues in other humanities disciplines, this report has identified three key themes that set the field apart—and point the way toward significant transformation on the horizon. Below, we summarize these findings toward offering recommendations for how academic libraries, archives, academic departments, professional societies, and software and platform providers can support scholarship in languages and literature. We also discuss how our findings resonate in the COVID-19 era.

The Language and Literature Scholar’s Unique Workflow

At first glance, a language and literature scholar’s approach to carrying out their research may appear similar to, say, a history scholar’s[71]—they read articles and books, visit archives, search multiple online databases and catalogs, and browse the stacks. On further examination, however, nuances emerge. Most language and literature scholars focus their research on a core text or corpus of core texts—with “texts” broadly defined as artifacts of human discourse. Investigations into historical context, theoretical frameworks, and literary comparisons flow from their curiosity about these texts.

This methodological approach has important implications. On the most basic level, the focused scrutiny and annotation of texts—ideally in physical formats, as discussed below —is critical. The pattern of core-text-focused research also informs the ways in which language and literature scholars go about searching for relevant materials. In the early phases of research they dip in and out of the archives and scholarly literature, following questions and leads raised by their core texts in search of fruitful research avenues. Rather than seeking an exhaustive view of the relevant material, they identify the theoretical conversations and contextual details that best illuminate their texts, often guided by the advice of their peers. This is a process that favors discretion—the ability to sniff out materials that resonate—over comprehensiveness. It is also a laborious and haphazard one. Language and literature scholars seem to embrace or even relish the labor of discovery, and want their graduate students to do the same.

Physical and Digital, in Tension and Harmony

Research in languages and literature increasingly straddles the material and digital—both in terms of scholars’ workflows and their objects and methods of study. In this discipline, attitudes toward materiality and the digital are complex and at times paradoxical. Today, digitization and the proliferation of online search tools allow scholars to engage with texts that were previously inaccessible—yet scholars continue to value, or even romanticize, the serendipitous discovery of physical texts. Language and literature scholars take pride in their personal “libraries” of hand-annotated print copies while also amassing large digital collections of PDFs and eBooks. And the influence of material culture studies, with its emphasis on the book as a physical object, has now been joined by new strains of scholarly discourse focused on theorizing the digital realm. The ambivalence of most language and literature scholars toward the specter of algorithmic bias is also important to note.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it would have been reasonable to predict that language and literature scholars would not easily follow their STEM colleagues in adopting almost fully digital workflows. Of course, this is no longer a safe bet. The slashing of library print collection budgets[72] and simultaneous scurry to make more academic materials available online;[73] the long-term disruption of travel; and widespread closures of physical libraries and archives are likely to jolt at least some scholars into digital work habits .[74] But the field’s bent toward serendipitous and selective discovery demands unique technological solutions that mirror analogue experiences. It is also possible that language and literature’s unapologetic love of close reading and the physical object will distance its practitioners from institutional leaders inclined to measure a department’s value by metrics such as the number of students who take a class, minor in a language, or find employment based on language-based skills—particularly in a climate of extreme fiscal uncertainty.

Another important area of disruption is engagement within the scholarly community. At the time of data collection for this project, perspectives on the value of online networking varied significantly among interviewees. Now it appears that the COVID-19 pandemic may nudge more scholars to join their peers in leveraging digital networking tools such as Facebook groups, listservs, and Twitter to communicate with their peers, crowdsourcing bibliographies and announcing their latest publications. As language and literature scholars increasingly recognize the benefits of online engagement, a strong “digital footprint” is being added to the implicit list of must-haves for graduate students vying for academic jobs.

These digital trends—in combination with growing concerns about equity and environmental impact—were already threatening the role of in-person conferences as venues for networking among scholars. With in-person conferences out of the question for at least the near-term future, many have proclaimed the death of the traditional conference as we know it.[75] It remains to be seen whether technological affordances, ranging from “matchmaking” apps[76] to 3D virtual reality conferences,[77] will preserve the conference’s function as a networking venue—or whether asynchronous forms of digital engagement will suffice to fill the gap. By contrast, one aspect of conference-going that appears relatively easy to adapt to remote formats is the opportunity to get focused feedback on work in progress from interested peers.

New Methods in Old Systems

While a minority of scholars have embraced digital humanities and public humanities methodologies, most remain cautiously curious—appreciative of their colleagues’ innovative projects but unmotivated to embark on similar work themselves. Reasons for this conservatism include a lack of digital or public communication skills and contentment with traditional research methods. However, by far the greatest barrier to embracing digital and public humanities work is the incentive structures of academic hiring, tenure and promotion. In an environment of fierce competition for academic jobs, it is usually in a scholar’s best interest to focus on producing prestigious monographs and journal articles—even in a context where any work which makes new materials available online has taken on outsized importance. For this reason, graduate students and tenured professors are the most ambitious practitioners of digital humanities and public humanities.

Nevertheless, there are indications that the tide may be turning. There is a sense among language and literature scholars that the formal recognition and evaluation of digital humanities projects for tenure and promotion is long overdue. As one scholar put it, “Everybody’s talking about, ‘we really need to get away from the book and article,’ but it feels like one of those things where everybody’s waiting until Harvard does it, or something like that.” The importance of online pedagogy in the pandemic context may also favor those candidates who can demonstrate the most dynamic digital engagement strategies; perhaps digital humanities researchers will have a leg up in securing what few jobs remain. However, the continued importance of peer review in the eyes of scholars means that digital projects are unlikely to play a prominent role in tenure and evaluation assessments until they can be formally assessed through a comparable process.

By contrast, the move toward public humanities has been fueled by rhetoric around convincing the public of the value of the humanities and, more concretely, some scholars’ sense of ethical obligation to the communities they research. The COVID-19 pandemic and renewed attention to systemic racism in the United States have added new dimensions to these important conversations. Our interviews, conducted prior to the pandemic and the death of George Floyd, returned few indications that public humanities research would occupy more than a supplementary place in tenure and promotion processes in the near future. Whether recent events will spur language and literature faculties to materially shift this trajectory remains to be seen.

The future of the discipline?

When asked about digital humanities and public humanities, interviewees frequently talked about graduate students’ projects. While the career aspirations and research practices of graduate students themselves lie outside the scope of this report, it is clear that language and literature scholars are observing a transformation in modes of scholarship among the next generation of scholars. Many believe that it is more important for graduate students to acquire digital and public communication skills than for established researchers. For example, digital humanities skills are increasingly listed as criteria in tenure-track job descriptions posted to the MLA Job List.[78]

Although digital humanities and public humanities are closely related in many language and literature scholars’ minds, it is important to note differences in the positionality of the two movements. Graduate students’ enthusiasm for digital humanities work—and the corresponding need for graduate training in digital skills—was often mentioned by interviewees in the context of academic careers. In other words, scholars implicitly predict that digital methods, outputs, and theories will continue to gain currency in the discipline.

By contrast, some scholars believe that public humanities training and research would particularly benefit graduate students exploring “alt-ac” career paths, or careers outside the academy.[79] “More and more we need to think about, okay, what else can our students do because there are only so many jobs available in our field. . . . I mean sometimes they can’t even write for an audience that’s bigger than five people,” one scholar mused. In recession conditions, graduate students are likely to increasingly demand transferrable skills,[80] even as leaders within the discipline call for universities and funders to retain the current generation of academic talent by supporting adjunct faculty, preserving tenure-track positions and creating new postdoctoral fellowships.[81] The discipline of languages and literature may be facing a bifurcation, in which digital humanities research is accepted as mainstream scholarly discourse while public humanities research is used to equip students for careers outside the ivory tower.

Recommendations

Accelerating Discovery

Center discovery on core texts. Most language and literature scholars search for archival materials and scholarly literature that are relevant to their core text(s), rather than the other way around. Providers of discovery platforms and catalogs should build tools that create links between authors or titles and thematic keywords. On the analog side, liaison librarians should keep track of what texts and authors scholars in their departments are working on.

Activate liaison relationships. A few language and literature scholars sing the praises of librarians alerting them to new materials unprompted. For academic libraries to make these fruitful relationships the rule rather than the exception, liaisons must proactively reach out to faculty members. And they must do so with even greater intentionality in fully or hybrid remote work contexts.

Prioritize diverse collections. The discipline of languages and literature is increasingly taking a global outlook. However, non-Western collections are both less available online and harder to locate. As deep learning engineers improve OCR in non-Roman alphabets, archives should direct resources toward digitization projects and finding aids for these collections. Embracing new crowdsourcing tools such as Sourcery may further improve access.[82]

Make discovery social and (seemingly) serendipitous. Language and literature scholars don’t conduct exhaustive literature reviews—instead, they trust their peers and their own instincts to help them identify the scholarly conversations that matter most, often serendipitously. Providers of discovery tools and peer-to-peer research sharing platforms should continue to improve recommendation algorithms, including by analyzing the browsing activities of similar users. Software providers should also consider integrating crowd-sourced bibliographies, such as those currently hosted by Zotero.

Recognize that scholars prioritize effectiveness. Issues around algorithmic bias in search engines are not on most language and literature scholars’ radar. By default, they will continue to use the search tools that most easily return the best results—including Google—although many also have a vague sense of unease around for-profit business models. Discovery platform providers should recognize that the current demand is for tools that work well and, if possible, are not implicated in corporate profiteering. To the extent that educating scholars about algorithmic bias is a priority for librarians, they must seek novel strategies for demonstrating its importance to scholars.

Building Research Skills

Leverage peer-to-peer education. Language and literature faculty members are unlikely to engage with library instructional programs for research skills because they believe they don’t—or shouldn’t—need instruction at all. Educational initiatives in which faculty “ambassadors” champion new tools or spread awareness among their peers are more likely to produce results.

Teach copyright and licensing basics. Many language and literature scholars are confused about what rights they have to reproduce and disseminate published versions of their own work, particularly on online platforms. Librarians should seize this opportunity to step in as advisors on copyright and licensing basics.

Train graduate students in bibliography. When surveying scholarly literature, language and literature scholars prioritize deciding “whose voice matters” over achieving exhaustive coverage. Libraries should partner with academic departments to train graduate students how to use catalogs, databases, archives, and the scholarly literature discerningly to find the resources they need.

Connecting Scholars

Build social tools to engage on a variety of scales . . . Although language and literature scholars typically work individually, they rely on peer networks for ideas, advice, and publicity. Moreover, they engage with these peer networks on different platforms at different points in the research lifecycle. If software providers want to displace juggernauts like Facebook and Academia.edu in this space, they should focus on specific functions, such as peer discussion groups, closed-group “workshopping” of works in progress, or wide-audience advertising of finished products.

. . . and integrate into existing workflows. It is also noteworthy that listservs, the networking tool favored by many language and literature scholars, are both low-tech and fully embedded in the routine of checking email. Software providers must ensure that offerings for language and literature scholars enhance existing workflows, rather than attempting to create new ones.

Shape conferences to facilitate work-in-progress discussions. The future of academic conferences is uncertain. Our data suggests that language and literature scholars think of conferences as opportunities to publicize and obtain feedback on research findings before attempting to publish. Professional societies seeking to determine the role of the conference in the pandemic context should shore up this function by experimenting with online formats that encourage constructive feedback.

Fostering New Directions

Pioneer new peer review processes. There is a growing impatience among language and literature scholars with the discipline’s inability to systematically assess and recognize digital humanities projects. At the same time, peer review appears unlikely to cede its place as the gatekeeping mechanism for academic work. Professional societies should take the lead in building frameworks and processes for peer review of digital humanities scholarship—which academic departments should then advocate to adopt in their tenure and promotion processes.