When Research is Relational

Supporting the Research Practices of Indigenous Studies Scholars

Executive Summary

In 2017 Ithaka S+R launched a project to explore the changing research methods and practices of Indigenous Studies scholars across Canada, the US, and Hawaiʻi with the goal of identifying services to better support them in ways that are also beneficial to Indigenous communities more broadly. The project was undertaken by a cohort of research teams at 11 academic libraries with guidance from a group of advisors comprised of Indigenous scholars and librarians. Each research team in the cohort developed findings and next steps based on their local research engaging with Indigenous Studies scholars at their own institutions (listed in Appendix 1). Ithaka S+R has the deepest gratitude to the researchers, research participants, and advisors for contributing their time and insight to the Indigenous Studies project.

The goal of this report is to serve as a companion piece to the local research undertaken by the cohort participants. In this report we provide comprehensive details on how the project was developed, designed, and fielded, and highlight key themes that emerged across the cohort as represented in their public outputs and presentations to date. The report concludes with final thoughts on how the project and its findings relate to how libraries and the Western academy can support research within Indigenous research paradigms.

Introduction

Ithaka S+R is a not-for-profit research group with a mandate towards understanding the evolving context of higher education, including issues of importance to stakeholders who support scholarly research, including libraries, museums, publishers, and scholarly societies. Through over 15 years of pursuing this research agenda Ithaka S+R has developed a certain kind of expertise in scholars’ information activities, such as through a triennial US faculty survey and in-depth studies on research activities of scholars by discipline through our ongoing Research Support Services program. [1] This work has been the basis for exploring new models for research support services, such as described in recent issue briefs on liaison librarianship and re-orienting research support around scholars as collectors.[2]

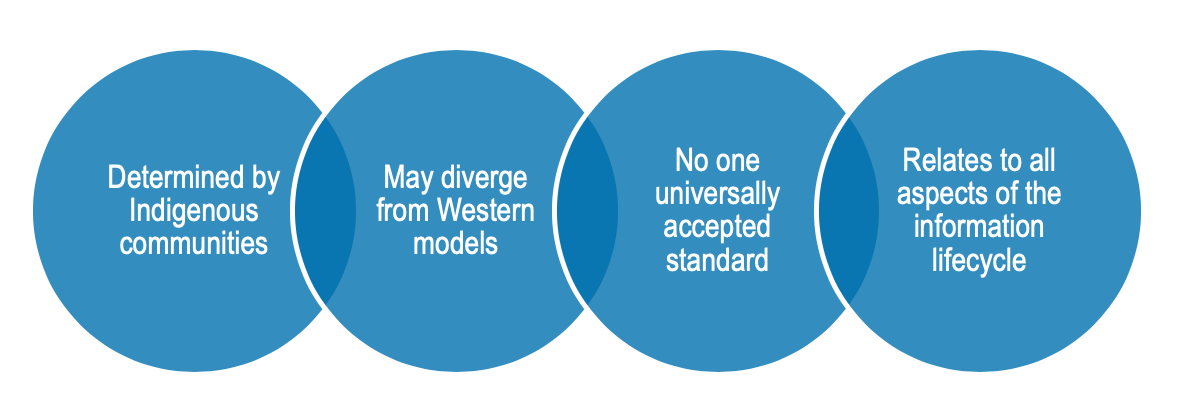

About three years ago it was suggested that Ithaka S+R develop a project on Indigenous Studies as part of its ongoing research agenda to understand scholars’ research activities and support needs. Ithaka S+R had no background in Indigenous Studies, and we knew, at the very least, that our particular expertise was not enough in and of itself to position us to lead a project on Indigenous Studies, which places Indigenous perspectives at the center of inquiry.[3] As part of that work, Indigenous Studies scholars may work within Indigenous knowledge paradigms, which involves unique protocols for defining, describing, sharing, and preserving information.[4] Scholars working within Indigenous Studies require information services and tools that are unique to the research supports typically found in Western institutions, including those provided by academic libraries, archives, museums and special collections. Building ongoing, meaningful relationships with Indigenous Studies scholars and understanding their work is an essential way for those who have mandates to support Indigenous Studies scholars at their institutions, such as academic librarians, archivists, and administrators, to develop services to fulfil those mandates.

A holistic perspective: Placing Indigenous perspectives at the center of inquiry

The interwoven characteristics of Indigenous information protocols

Before pursuing this project, we commenced a period of internal reflection and exploratory discussion with leaders in Indigenous Studies and Indigenous librarianship to understand if such a project spearheaded by Ithaka S+R would be of benefit to those communities, and if so, how it would make sense to proceed with developing it. We are grateful to Te Paea Paringatai,[5] Camille Callison,[6] Deborah Lee,[7] Loriene Roy[8] and J. Kēhaulani Kauanui[9] for their guidance and patience as advisors as Ithaka S+R explored the possibilities for developing a research project. With their guidance, we moved forward in collaboration with a group of academic libraries to study the evolving research support needs of Indigenous Studies scholars. Academic libraries and organizations like Ithaka S+R can be allies in this work only insofar as the project could be developed in ways that would honor Indigenous communities and their knowledge protocols and lead to meaningful change within mainstream academia. Given this, Ithaka S+R needed to change the methodology used in previous research support services projects.

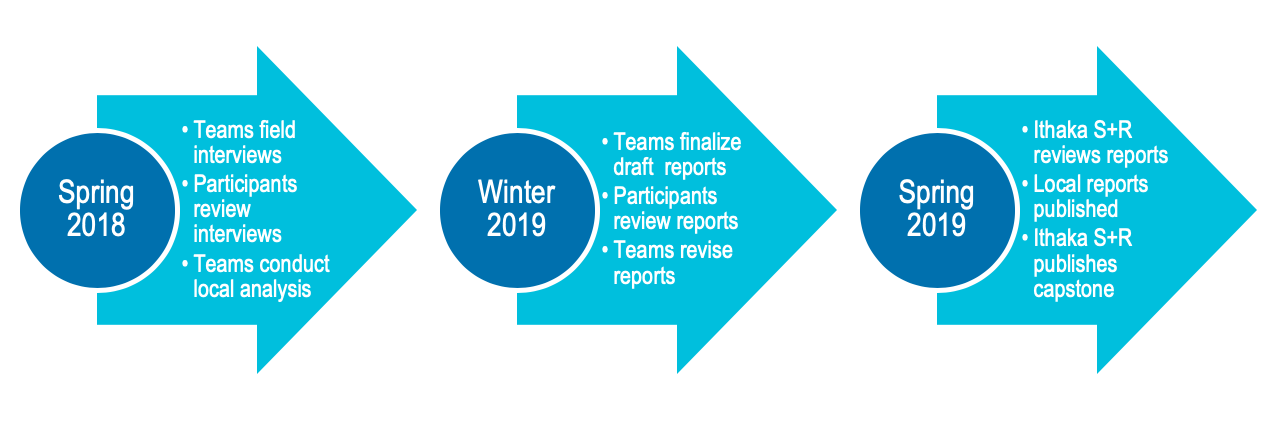

The project became a research study collectively undertaken from 2018 to 2019 by teams at 11 academic libraries to interview Indigenous Studies scholars on their research experiences and support needs.[10] The teams shared an approach and instruments that were reflective of Indigenous methodologies and which could be sufficiently adapted to lead to separate findings and next steps relevant to each local context. The reports from teams who chose to make some of their findings public are being released concurrently by each institution as companion publications (see Appendix 1).

The Ithaka S+R Indigenous Studies project timeline

This report shares how the project was developed and reflects on how this process, and the findings developed by the participating research teams, relate back to the project’s underlying goals. In describing how the project was developed we want to highlight what emerged as a significant finding throughout the research: the importance of respect and relationship building when engaging with those who work with Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous knowledge keepers and creators. This is a theme that is woven throughout this report and the reports by the local research teams, and we are grateful to the researchers and their libraries for their commitment to undertaking this work with us. This report does not simply represent the ending to a particular project, but rather a contribution to the vital ongoing work of honoring and fostering Indigenous ways of knowing in academia.

Creating the Project

The underlying aim of this project is to contribute to ongoing research examining how mainstream cultural institutions, including libraries, archives and museums, contribute to – and can begin to rectify – historic and ongoing practices of colonization and foster Indigenous approaches to librarianship. Understanding how Indigenous Studies scholars conduct their research by engaging in dialogue with them about their practices can help identify tools, policies, and services for working with Indigenous information that do not re-inscribe colonial practices and that foster Indigenous approaches to working with information. This exchange of knowledge is helpful insofar as it is also part of an ongoing process of developing meaningful relationships with Indigenous Studies scholars.[11]

Margaret Kovach emphasizes that due to the multi-layered, holistic nature of Indigenous Studies, engaging with the field “involves both process and content work.”[12] At the core of this project is a commitment to honoring Indigenous research protocols, not only by conveying findings about Indigenous Studies scholars’ experiences working with information, but also by creating and enacting research processes during the project that are consistent with those protocols. As is further outlined below, essential to this approach was developing processes that would enable the cohort to engage in a research project with shared aims while also having sufficient flexibility to enact their respective local components of the study to reflect and honor the unique contexts and needs of their scholars and larger institutions.

Relationship Building and the Cohort-Based Approach

Indigenous research approaches take a holistic worldview of knowledge creation, emphasizing cooperation and connectivity. Recognizing this has implications for every aspect of designing a research project, as the relationship between researcher and research participant is of fundamental importance.[13] Given this, it was determined that academic librarians who have a mandate to support Indigenous Studies scholars at their own institutions would be ideal research partners.[14]

Participation in the cohort was open to any higher education institution in the US and Canada with the interest and capacity to participate in the project goals and approach, particularly around a commitment to learn from and develop meaningful relationships with Indigenous Studies scholars.[15] Each institution in the cohort developed their own team of researchers to conduct the local component of the study.[16] Working with the advisors, we also identified schools to invite to the project that had similar interests to the project aims and that would allow us to achieve broader geographic representation. Appendix 1 lists the participants on the institutional research teams.[17]

In addition to facilitating relationships between the researchers and the research participants, the cohort-based approach also had the advantage of creating relationships between a group of researchers with shared interests, both at their own institutions and across the participating institutions. At the outset of the project the cohort convened at training workshops at the University of Alberta on November 2-3, 2017 and at Haskell Indian Nations University/University of Kansas on December 13-14, 2017 to become collectively familiar with project’s approach and engage with local Indigenous Studies scholars and local Indigenous culture.[18]

Researchers learn from Sierra Two Bulls (top) and Jancita Warrington (bottom) at the Haskell Cultural Center and Museum during the project workshop[19]

Throughout the project cohort members continued to connect through email exchanges, a remote meeting to share writing processes, and by developing a variety of conference engagements.[20] These opportunities were of particular value in allowing participants to learn from the other researchers’ experiences, processes, and emerging findings. We emphasize this especially for those considering developing projects with similar approaches.

Methods of Direct Inquiry

Reflecting that the local research teams were best positioned to engage with scholars at their institutions, the methods of direct inquiry were conducted exclusively by those teams as opposed to Ithaka S+R.[21] The primary mode of direct inquiry with the participants was semi-structured interviews, which were approximately 60-90 minutes in duration, and an iterative process of coding, analysis, and writing up based on what was learned from the interviews to further develop understanding.[22] These direct processes of inquiry were interwoven with continuous engagement with the participants, to ensure that the goals of and meanings derived from the project remain shared.

Each participating research team conducted interviews with a series of Indigenous Studies scholars at their own institutions.[23] We structured the interview guide to capture how research is conducted holistically through developing a program of research and engaging with the field, working with information sources, generating and managing data, and communicating findings.[24] In recognition that Indigenous Studies is multi- and inter-disciplinary, the semi-structured interview guide was designed to flexibly accommodate discussions with scholars across a variety of fields. In order to recognize and foster the relationship between the interviewer and interviewee, their connection to the research, and to acknowledge how these relationships are part of a larger holistic context, the interviews begin with the interviewer talking about who they are and inviting interviewees to ask any questions of the researcher that would be helpful for them at the outset of the interview.[25] The guide was also designed to provide the fullest possible breadth of questions and suggested prompts to accommodate the sheer variety of research approaches that Indigenous Studies scholars implement, and interviewers were given flexibility in determining which questions to work with on an interviewee-by-interviewee basis.[26]

The research teams continued their direct inquiry following the interviews through an iterative process of analyzing the transcripts and writing up the results.[27] During this process the teams shared an underlying goal to attend especially to what participants identified as their research support needs towards developing ideas for improving library services. While doing so, the teams also had full flexibility to design a process of analysis and reporting that would work best for them, their participants, and their institutions. Further information about the teams’ written outputs can be found in the following section. Each team developed their interviews into a corpus of transcripts and then developed their own unique process to derive meaning from those transcripts.

Communicating Findings

Each team created a local report to communicate findings and identify opportunities for improving services at their library accordingly. The teams had full agency in determining the process of writing and structuring the reports and whether or not to make the reports publicly available. This flexibility was built into the project in recognition that the teams would be in the best position to determine, in conjunction with their participants, how and which findings should be presented. Some teams are also developing other outputs from the data to ensure that they can reach as many relevant audiences as possible and communicate the fullest breadth of findings. This includes other engagements with scholars, librarians, and administrators at their institutions, and presentations and publications for wider audiences, including for those in Indigenous Studies and the information professions. Communicating findings beyond the formal project output of the public local reports is essential to ensuring that different audiences can be reached effectively.

Engaging with Participants

Attending to how the research teams engaged with their participants was an important part of the project methodology. Placing emphasis on relationship building in complement to the direct inquiry framework reflects Indigenous research approaches. Indigenous research approaches recognize that knowledge is created holistically, and, by extension, that privileging ways of learning through direct inquiry over other forms of engagement is an artificial and potentially damaging approach to research.

Prior to undertaking the formal inquiry, each team engaged with stakeholders at their institution, including prospective participants and other affiliates, to determine whether it would be worthwhile to proceed with the project, and if so, how to proceed accordingly. This enabled each team to build relationships with those whom they were seeking to engage as part of the study and to incorporate their feedback at an early stage. These meetings were intended to be conducted in ways that would be preferable for those they were seeking to engage and included hospitality, such as being taking out prospective participants for coffee.[28] At this stage some teams identified local adjustments to ensure they could proceed in the best possible way. It was at this point that many of the teams confirmed the importance of privileging engaging with Indigenous Studies scholars who self-identify as Indigenous in recognition of ongoing under-representation of Indigenous perspectives in academia,[29] and to incorporate student representation.[30] Some teams also determined that it would be important to solicit participation only from faculty whom they had already begun to develop relationships with prior to the project.[31]

Fostering an ethos of reciprocity and relationship building continued as the project moved into the period of direct inquiry. In addition to working with an interview guide developed to foster dialogue, the teams ensured that interviews would be conducted in spaces where participants felt the most comfortable, and some teams also gave gifts to their participants at the interviews in recognition of their contributions.[32] Following the interviews each team gave their participants the opportunity to vet the transcribed version of their interview and how their interview was included in the resulting local report. The teams also solicited the interviewees’ feedback on the report and its recommendations more widely. Participants were also given full agency about how their contributions to the report were recognized, including deciding whether or not to be publicly identified.

Project Findings

A common thread throughout the interviews and subsequent reports is how scholars conceptualize their research through the lens of Indigenous Studies, including the personal journeys of coming to and developing methodological approaches to the work. Reflecting this, the first section out of this report describes how findings pertaining to the knowledge practices of Indigenous Studies relate to specific information experiences and needs when conducting research. This is outlined further in the subsequent sections on project findings about working with information collections and gray literature, managing information, and sharing information and articulating its value.

Contextualizing Indigenous Studies as Practice

Similar to the experiences of developing the methodology for this project, participants emphasized how Indigenous Studies approaches may utilize a variety of methods, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, and that what unites the research is the commitment to putting Indigenous perspectives at the center. Woven through these accounts are many observations about how being an Indigenous Studies scholar grounds every aspect of conducting research, including the spaces where scholarly work takes place, and the processes of working with information, as an extension of how one relates to the Western academy more widely.[33] For example, Indigenous frameworks privilege relationship building, and by extension, how knowledge is created relationally, including through oral traditions. Scholars for this project emphasized how Indigenous community members, particularly Elders, were equivalent to primary sources.[34] As is explored further in subsequent sections of this report, the centrality of relations with people and particular spaces feeds into how scholars work when consulting information, their needs from the institutional spaces they work in, and their priorities in how their research and research more widely is credited and shared.

At the heart of Indigenous inquiry are Indigenous languages, because communication is integral to knowledge formation and is a carrier of culture and worldviews. Working with and within Indigenous languages is important for centering the research on Indigenous perspectives and within the Indigenous worldview. Scholars reflected on the importance of learning the Indigenous languages relevant to the communities they work with and study, and working with others with language knowledge to better contextualize the information contained in the sources they consult.[35]

Indigenous language support and support for Indigenous language revitalization efforts more broadly are highly important for fostering Indigenous Studies as a field.[36] As discussed later in this report, scholars see opportunities for the library to support these revitalization efforts by having Indigenous language spoken in libraries and more visually present in library spaces, collecting difficult-to-acquire language learning texts developed by Indigenous communities, improving metadata to include more consistent use of Indigenous language, and creating spaces such as language labs to support learning. There are also important contributions that could be made within the scholarly communications realm by fostering Indigenous language use in publishing.

While this project focused on Indigenous Studies scholars research practices, scholars shared how teaching feeds into their research and vice versa, which also reflects the holistic nature of Indigenous knowledge processes. Teaching students within Indigenous Studies frameworks and guiding them on research projects is a crucial component to building the field.[37] Therefore, the findings below are not only reflective of the research support needs of individual Indigenous Studies scholars, but also of needed supports for their teaching as they mentor students on their research paths.

Working with Information Collections and Gray Literature

Many scholars interviewed for this project identified working with archives and special collections, including collections held by various levels of government, academic institutions, and in various community contexts, as a component of their research processes. They shared how working with these collections from the vantage of Indigenous Studies, which places Indigenous perspectives at the center of inquiry, necessitates unique approaches to navigating these collections. Literacies in Indigenous languages, cultural protocols and other cultural understandings are important to navigating primary content.[38] Scholars highlighted how working with Indigenous community members can be an important strategy to help navigate and provide helpful context to what is found in the historical record.[39]

Critical literacy skills are also required to effectively identify information that sheds light on Indigenous experiences when working with documents that were created by and collected through colonial contexts.[40] The records can include disturbing and derogatory content which can be emotionally challenging to navigate.[41] Some of the Indigenous-identified participants in the project also explained how the content can have personal and affective dimensions because it documents the history of their family or larger community, sometimes revealing information that they did not know previously and/or representing a rare source pertaining to a particular person, language, or other knowledge.[42]

Discovery and access to archival and special collections was identified by many scholars as a major barrier. Discovery tools for archives and special collections are often ineffective, and policies for access create further barriers. For example, content in many collections can only be accessed in person at particular hours, and collections may not be processed.[43] Inconsistent and racist metadata about collections, particularly around people and place names, was also noted as a particular challenge when working with Indigenous content.[44] Experiences working in archival settings, positive or negative, can also have effects on scholars and the extent they work with these kinds of collections.[45] It can be challenging when information workers act as gatekeepers or lack the cultural knowledge to adequately support research in an Indigenous context. Conversely, positive experiences in archival settings can lead to lifelong professional partnerships.

Training and improved digital discovery and access tools were identified as ways to improve experiences working with archives and special collections.[46] Improved discovery and access of archives and special collections is important not just for scholars, but also for Indigenous community members towards their self-determination.[47] However, there is also an awareness that digitizing primary content is not a panacea and that digitization projects must involve careful consultation and planning with families and communities represented in the content.[48] Additionally, in some cases archives and special collections should prioritize repatriating content back to Indigenous communities.[49]

In addition to working with archives and special collections, scholars interviewed for this project also spoke to their experiences working with library collections. Here, too, many encounter challenges particularly around discovery, such as racist library classification headings and accompanying metadata and inconsistent naming practices.[50] Scholars seek out information across traditional disciplinary boundaries, develop critical literacy skills, and work within their own networks to effectively identify and work with published information in these contexts.[51] Some scholars have also been able to develop meaningful relationships with librarians and archivists over the course of their research. These scholars characterize librarians and archivists as providing vital guidance, characterized by collaborative, non-client-based models for working together.[52]

In both general and archives and special collections contexts, scholars see a need for increased collection of new content, such as books by Indigenous authors, including those that are self-published in academic library contexts, and digital artifacts circulating through Indigenous social media networks.[53] The need for collecting content on Indigenous law is particularly acute due to lack of digitized sources and comprehensive databases.[54] Some scholars also highlighted the gatekeeping function of academic libraries more widely and suggested that Indigenous communities should be granted access to libraries’ journals and books as a way of giving back.[55] Opening up libraries can also be achieved by attending more closely to library as place, with some participants making positive observations about distinctly Indigenous spaces and visible Indigenous collections and offering recommendations for other ways to make the spaces more welcoming, such as through ceremonies and language.[56]

Gray literature, or materials and research created by organizations outside of mainstream commercial and academic publishing and dissemination channels, are an important source of content for Indigenous Studies scholars. Scholars interviewed for this project spoke of a variety of types of gray literature they rely on in their work, including non-Indigenous and Indigenous government content and other forms of Indigenous community content from a variety of geographic locales and in numerous formats.[57] This content is challenging to work with because it is not typically collected by any one institution as a collection or with particular preservation strategies, which makes it difficult to discover and access in a stable manner over time.[58] Scholars interviewed at the University of Saskatchewan made specific reference to the Indigenous Studies Portal, a tool that has been developed to capture Indigenous gray literature primarily from across Canada among other forms of content.[59]

Managing Information

Indigenous Studies is a multi- and interdisciplinary field, and the kinds of information scholars for this project reported working with, creating, and collecting over the course of their research reflect that variety. They include personal notes, photographs, copies of images and documents, archaeological site data and documentation, interview recordings and transcripts, maps and other GIS data, and oral and government data. Referring to these forms of content exclusively as “data” may be too narrow in research contexts working with more expansive approaches to Indigenous knowledge, and it can be especially challenging to manage both information in emerging and evolving digital formats and the unique artifacts and materials reflective of Indigenous ways of knowing.[60] Scholars also amass personal collections of materials published or self-published by Indigenous people and communities that are difficult to acquire through mainstream libraries and bookstores. As in other fields,[61] scholars described a variety of idiosyncratic, ad hoc processes for managing the information they collect and create over time, reflecting a variety of needs and opportunities for further support in these areas. Indigenous approaches to quantitative research are anticipated to develop over time, which will necessitate further support needs in the future.

Scholars interviewed for the project communicated that they have strong stakes in how the information they create, collect, and work with is organized, shared and preserved over time.[62] This is not only because information preservation and management impacts their abilities to do their own work, but also because of Indigenous rights to information sovereignty for any information pertaining to Indigenous peoples and communities. The findings from the reports in this project show that much more work needs to be done by libraries, their institutions, and other stakeholders to understand and support the unique information needs related to Indigenous data management and sharing.

Scholars discussed the complexity of concurrently navigating university, government, and community protocols for managing and sharing the information they work with during their research, and also of keeping pace with technological advances in these areas.[63] For example, scholars may need to negotiate around default protocols by universities and governments that privilege eventually destroying information when the content represents important cultural heritage that should be kept and preserved in the long-term with input and oversight from the community.[64] Universities and governments may also mandate the use of third-party proprietary information management and sharing platforms, such as iCloud or Google Drive, which may potentially result in diminished information autonomy, greater vulnerability to security breaches, and inadequate infrastructure for long-term preservation.[65] Digital infrastructures designed to share information collected by Indigenous communities in ways that honor Indigenous rights to self-determination in description and access, such as Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR) and Murkurtu, can be important to facilitating respectful information preservation, organization and sharing processes.[66]

Sharing Research and Articulating its Value

Reflecting the underlying goals of research informed by Indigenous methods, the scholars across the institutions interviewed for this project shared a major priority for making their research more widely accessible and beneficial in ways that honor Indigenous communities. This work begins even before the findings from projects are formally published, with some scholars describing processes of seeking input from the Indigenous communities their research engaged with on drafts of the research reports and in the planning for where and how those findings will be shared with the community and more widely.[67] This kind of vetting can be considered a form of peer review and can be as important as formal academic peer review.[68] Some scholars also seek to recognize the contributions of Indigenous community members engaged in their research through co-authorship.[69]

Scholars described how the mechanisms for sharing findings with Indigenous communities engaged with their research can take a variety of forms, including sharing PDFs of publications, creating informal summaries of the research, speaking at community forums, appearing on radio shows and at community events, developing videos, providing reports to tribal councils, facilitating classroom discussions at local schools, and publishing in newspapers.[70] Scholars also noted that social media is a helpful tool for being more visible within and connected to Indigenous people, particularly through Facebook and Twitter. For this reason social media was also recognized by some scholars as an important tool of information discovery for themselves and others. [71]

In contrast to the venues listed above, publishing work in open access scholarly journals was not commonly mentioned by scholars as a mechanism they currently use to make their research more widely accessible. Some acknowledged that while they are not currently engaging in open access publishing, it has some potential to further their aims because it is consistent with their perceptions that Indigenous communities should have full access to all forms of publications their contributions are featured in.[72] While open access scholarly publishing may help break down access barriers, there are also other forms of inaccessibility, such as the academic writing genre, which are not fully ameliorated by open dissemination channels.[73]

Scholars described a variety of challenges in their efforts to share research with Indigenous communities. These efforts, like efforts throughout the research process to engage meaningfully with Indigenous communities, require considerable time, effort, and resources but also often cannot be captured by formal Western university recognition systems, such as tenure and promotion.[74] Engaging in these processes can feel counter-intuitive alongside Western academic training, particularly when pursuing the PhD, where limits are placed on how, when, and to what extent findings should be shared.[75]

Scholars also described a series of challenges in how they share their research within academic communities. Some scholars are very committed to supporting newer interdisciplinary publications aligned with the emerging field of Indigenous Studies but are also concerned that these publications are perceived as having less impact or prestige than more established titles, including during hiring, tenure, and promotion.[76] These sentiments also reflect the broader concerns scholars shared about how their research trajectory is perceived and evaluated by the Western academy, including their peers’ lack of familiarity with the value of Indigenous methods and interdisciplinary methods more widely, as well as the lack of mechanisms for recognizing this type of work.[77]

These concerns were reflected in the challenges that scholars described when pursuing publication in more established Western academic publishing venues. Peer review committees were commonly described as having a lack of awareness of or inadequate experiences with evaluating Indigenous methods and terminology.[78] Some participants in the sciences described the challenges of trying to publish work incorporating Indigenous research methods in more mainstream academic venues.[79] While having the opportunity to support emerging interdisciplinary Indigenous Studies publications has merit for some, there is also a risk that this approach leads to siloing, which exacerbates the perception that Indigenous research is less valuable or irrelevant to Western research pursuits.[80]

Conclusions and Next Steps

The Indigenous Studies project provided a unique opportunity for a cohort of academic libraries to come together, learn from Indigenous Studies scholars, and reflect on how those scholars’ needs can inform ways to improve research support services at their institutions and beyond. The findings from the project point to a variety of ways that this work can be continued and fostered anew. Crucially, this work requires contributions from and collaboration between a variety of stakeholders, including the Indigenous Studies scholarly community, Indigenous communities more widely, museums, archives, libraries, special collections, scholarly publishers, and digital tool providers, among others. We offer our findings towards informing that work, including how it proceeds, hoping to serve as an example of how research on and information services for Indigenous Studies scholars and, by extension, Indigenous communities must be developed through an ethos of mutual respect and beneficence.

In order to ensure that the research for this project has productive aims, each research team has identified opportunities and next steps for building on their findings to improve information support services in Indigenous Studies. Following the opportunity to read across those reflections, we conclude this capstone report by offering a series of recommendations that emerged through the project findings and through the process of developing and implementing the project. We look forward to continuing this important work with others and acknowledge how our ability to do this is due to the efforts of Indigenous librarians and scholars who have come before us.

Growing Institutional Capacity

Supporting Indigenous Studies research involves building the capacities of a variety of institutional capacities, including information workers, scholars, students, and administrators. Spaces and programming create fertile grounds for meaningful relationships.

- Spatial considerations in libraries, archives and special collections. Attend to how the spaces that research is conducted in can be made more welcoming through meaningful architecture and furnishing, display of Indigenous collections, Indigenous language use, and welcome events that respect and celebrate Indigenous cultures.[81]

- Cultural competencies. Libraries, archives, and special collections, in conjunction with their wider institutions, must engage in critical self-reflection about their role in colonization.[82] Affiliates with those institutions must also work towards greater awareness of Indigenous history, rights, language, culture, and protocols.[83]

- Professional competencies. Information workers and others involved in supporting Indigenous Studies research require unique competencies, including understanding of Indigenous information protocols and rights to self-determination, best practices in Indigenous information and data management, and Indigenous metadata.[84] Hiring and supporting Indigenous information workers and their leadership development, including students, is an essential part of this work.[85]

- Working with stakeholders. Workers in libraries, archives and special collections must engage meaningfully with Indigenous studies scholars and students towards improving information services, spaces and tools.[86] Support increased research capacity of Indigenous Studies scholars and students by providing the time to do it and recognize and understand why this is important.[87]

Broadening Opportunities for Information Discovery and Access

How and to whom Indigenous information is made available is a central consideration for fostering Indigenous Studies as a field. Reflecting Indigenous knowledge frameworks, these considerations often exceed Western academic strategies for information discovery and access.

- Subject headings, catalog descriptions, and other metadata. Metadata challenges such as inconsistent naming and problematic descriptions are a barrier to research and signal that collecting institutions are not respectful allies. Rectifying this involves work by individual archives, libraries, and special collections and collaborative endeavors, including leadership from professional organizations (e.g. ALA, ACRL, SAA) and appropriate community stakeholders. [88] [89]

- Non-published materials. The challenges of discovering and accessing certain kinds of information that aren’t formally published are particularly acute for content types such as oral histories, gray literature, and genealogical records.[90] It is unlikely that any one or even a group of libraries, archives, or special collections can tackle this. Governments and/or not-for-profit digital technology platform vendors are likely best positioned to develop broader solutions to these grand discovery challenges.

- Access for Indigenous communities. Building better relationships between Indigenous communities and the academy includes improving community access to scholarly content, such as by expanding institutional subscriptions.[91] Indigenous peoples have a right to know about research conducted on them and their communities, and access to this information should ideally be granted through programs that extend beyond individual institutions to ensure adequate community coverage.[92] Open access is not a panacea for these goals as Indigenous Studies scholars continue to navigate between their desire to communicate with Indigenous communities and the need to conform to publishing norms in their fields and in their institutions.[93]

Building Collections

Collecting institutions that are focused on offering information to those engaged with the burgeoning field of Indigenous Studies must focus on dynamic new content, and how working meaningfully with Indigenous communities is central to collecting work.

- Support Indigenous authors and Indigenous publishers. This work can be done by individual libraries and/or through consortia licensing or purchasing a wider array of content and by advocating for vendors to broaden their offerings as well.[94]

- Collect and preserve content in new media formats. Contemporary Indigenous culture is robust and is being expressed through new digital media and online dissemination channels. Archives and special collections are only in their infancy in understanding the most effective ways to build digital media into their historical collections, and preservation strategies are a crucial component to this work.[95]

- Honor Indigenous rights to information sovereignty. Digital repatriation and platforms that mediate who has access to information offer new opportunities for collecting institutions to respectfully engage with Indigenous communities in information stewardship.[96] Providing support so that Indigenous communities can build capacity for collecting and maintaining their own information collections is also an important component of the work that archives and special collections can provide.[97]

Researching Information Support Needs in Indigenous Studies

Conducting research on Indigenous Studies information practices can be a productive strategy for building evidence on how to improve information support services and build relationships with the field. Findings from this project point to key issues for information professionals to be mindful of when pursuing future research in these areas.

- Privilege Indigenous perspectives and worldviews. While Indigenous studies draws from a variety of methods, at its heart is a commitment to placing Indigenous perspectives at the center of inquiry. Research projects designed to identify Indigenous information support needs, including those of Indigenous Studies scholars, must reflect this in every aspect of the project, including how relationships are built with research participants and other relevant stakeholders, how input is gathered including direct methods of inquiry, and how findings are structured and enacted.

- Be mindful of project scope. Indigenous worldviews teach us about the holistic nature of knowledge creation, which can be challenging to honor through research conducted in Western academic contexts. For this project that meant aiming to do fewer but longer interviews on a broader scope of topics with maximum opportunities to engage with participants over the course of the project. It is important to recognize that the process of scoping must be determined on a project-by-project basis and requires considerable engagement and reflection.

- Build in adequate support for the researchers. Research projects that put Indigenous perspectives at the center take considerable effort and commitment on the parts of the researcher. This necessitates broader institutional support for the researcher’s time and energy, and a commitment to ongoing support for enacting the necessary actionable changes resulting from the work.

- Prioritize reciprocity. Indigenous methods teach us about the importance of designing research that is beneficial to both the researchers and the research participants. There is great potential for this ethos of reciprocity to be adapted to research on information needs more widely.

In addition to highlighting important considerations when developing research projects to better understand Indigenous information needs, the findings also are helpful for identifying directions for future research in this area by information professionals:

- Teaching supports. Many participants reflected on how teaching informs their research and vice versa, and how supporting Indigenous Studies students is an important component of developing the field overall. This highlights how research that further explores this dynamic and focuses more explicitly on teaching and student supports is worthwhile.

- Data practices. Quantitative approaches to Indigenous research is an emerging methodological area for the field. Since academic libraries and their wider institutions are only at the beginning of understanding how to support scholars’ data practices across the disciplines, it will be important to attend to the unique needs of Indigenous Studies scholars in this area.

- Geographic variations. The institutions that participated in this project capture perspectives of scholars in the US, Hawaiʻi, and Canada. Future projects that focus on Indigenous Studies scholars’ needs in other geographic contexts would be helpful for developing a more contextualized understanding.

- Design-oriented inquiry. Attending how to most effectively create the tools, spaces and services suggested through the project findings necessitates incorporating design-oriented approaches to inquiry. For example, when exploring how to improve Indigenous communities’ discovery of and access to scholarly literature and archival collections, attending to design is integral. Similarly, improving library spaces to make them more welcome to Indigenous students, scholars, and communities is also undergirded by design considerations.

Appendix 1. Research Teams and Local Reports

Dartmouth College

J. Wendel Cox, Ridie Wilson Ghezzi, Julia Logan, and Amy Witzel. Research Practices and Needs of Indigenous Studies Scholars at Dartmouth College: A Report Coordinated by Ithaka S+R, https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/dlstaffpubs/16/.

Haskell Indian Nations University/University of Kansas

Carrie Cornelius, Sara E. Morris, Rebecca Orozco, and Michael Peper. Research Support Services for the Field of Indigenous Studies, http://hdl.handle.net/1808/27712.

Northwestern University

Scott Garton, Michelle Guittar, Michael Perry, and Gina Petersen. Examining the Research Practices of Indigenous Studies Scholars at Northwestern University, https://doi.org/10.21985/N29R0W.

University of Alberta

Tanya Ball, Anne Carr-Wiggin, and Kayla Lar-Son. Rooting Stories and Branching Out: Research Support Services Study for the Field of Indigenous Studies, https://doi.org/10.7939/r3-5tdm-cx54.

University of Arizona

Michelle Nicole Boyer-Kelly, Verónica Reyes-Escudero, Anthony Sanchez, and Niamh Wallace. Research Practices of Indigenous Studies Scholars at the University of Arizona: An Ithaka S+R Report, http://hdl.handle.net/10150/631569.

University of British Columbia

Sarah Dupont and Kim Lawson. Research Support Services for Indigenous Scholarship at the University of British Columbia, forthcoming.

University of Hawaiʻi System

Kawena Komeiji, Keahiahi Long, Shavonn Matsuda, Annemarie Paikai, and Kapena Shim. E Naʻauao Pū, E Noiʻi Pū, E Noelo Pū: Research Support for Hawaiian Studies, http://hdl.handle.net/10125/44906.

University of Manitoba

Lisa O’Hara, Janice Linton, and Cody Fullerton. Libraries’ Support Services for Indigenous Research & Scholarship at the University of Manitoba, http://hdl.handle.net/1993/33591.

University of Saskatchewan

MaryLynn Gagné, Deborah Lee, and David Smith. Report on the Ithaka S+R Study on Improving Library Resources and Services for Indigenous Studies Scholars: University of Saskatchewan Context, https://harvest.usask.ca/handle/10388/11626.

University of Toronto

Jennifer Sylvester, Jennifer Toews, and Desmond Wong. Research Support Services for the Field of Indigenous Studies, http://hdl.handle.net/1807/93725.

Appendix 2. Semi-Structured Interview Guide

Pre-Interview Introduction

- Interviewer thanks participant for their participation, recognizes the participant’s expertise and knowledge contribution to the study, and acknowledges how this study contributes to a wider context of knowledge creation (including: the library and university in which the research is being conducted, other academic libraries, the wider academic community, and, society-at-large).

- Interviewer provides contextualizing information about the research project, including project background, the project methodology, and the structure of their engagement with the participant. Interviewer highlights that the participant has a choice about whether or not their responses, or a portion of their responses, remain confidential, and, that they will have the opportunity to review their transcript and how their words are invoked in the report towards this process.

- Consent form is reviewed and signed; audio recorder is turned on.

- Interviewer provides contextualizing information about themselves (e.g. their interest in the research topic, how they came to this work, their relationship to the participant)

- Interviewer invites participant to ask any questions about the interviewer, the research project, or anything else that would be helpful for participant, at this, or any point in the discussion

Participant Background

- How did you come to your work? [in the broadest sense of the term, e.g. background information about where they come from, how they came to academia and their research, how they came to this university, etc.]

- Describe your current research focus and current research project(s).

- What research methods and/or theoretical approaches do you typically work with to conduct your research? [e.g. decolonial approaches, oral history, ethnography]

- How did you develop your methodological approach? [e.g. through specific classes, key readings, trial and error, in consultation or collaboration with certain groups]

Working with Primary Sources

- Do you rely on primary source information to do your research? [“Primary” refers here to “primary sources,” or, an “artifact, a document, diary, manuscript, autobiography, a recording, or other source of information that was created at the time under study”]. If so,

- How do you locate this information? [e.g. “research tools,” with help from specific individuals]

- Do you have conversations with Indigenous community members around determining protocols for how this information is stored or shared? [e.g. plans for retention, destruction and sharing; meta-data used to describe collections and their access]

- Can you share a success story about finding and working with a valuable primary source? What were some factors that helped to make this a success story?

- How do you incorporate this content into your final research output(s)?

- Do you consult with individuals/communities around how this content is analyzed and incorporated into your final output? [If so, can you talk about how this consultation influences your written report, article, chapter, etc.?]

- Have you encountered any challenges in the process of locating or working with primary sources? If so, describe.

- Are there any resources, services or other supports that would help you more effectively locate or work with primary sources?

Working with Secondary Sources

- What kinds of secondary information do you rely on to do your research? [“secondary” refers here to “created later by someone who did not experience first-hand or participate in the events or conditions you’re researching” e.g. scholarly articles or monographs]?

- How do you locate this information? [e.g. research tools, with help from specific individuals]

- Do you have a story from your past related to your first experience learning about library online research tools? What was that experience like for you?

- Have you encountered any challenges in the process of locating or working with secondary sources? If so, describe.

- Are there any resources, services or other supports that would help you more effectively locate or work with secondary sources?

Working with Others

- Do you do qualitative or quantitative research with Indigenous community members as part of your research process? If so,

- Could you describe the nature of your most recent research project(s)? [e.g. is it ongoing? At what stage in your research process? In what capacity?]

- How would you describe your approach to doing qualitative or quantitative research with Indigenous community members and what literature or training has informed that approach? [e.g. specific literature, training workshops]

- What are some success stories you would like to share about doing qualitative or quantitative research with Indigenous community members?

- What is rewarding for you when you do qualitative or quantitative research with Indigenous peoples?

- Have you encountered any challenges during the process of doing qualitative or quantitative research with Indigenous peoples?

- Some Indigenous Studies scholars talk about the importance of developing ongoing, long-term relationships with Indigenous peoples, including those who may potentially become research participants, sometimes over the course of a lifetime. Have you engaged in this form of long-term relationship building, and if so, how has it informed your work?

- What has been most helpful for you in developing these relationships? [e.g. on-campus group on Indigenous community relations; soft skills training, i.e. learning patience; adopting a humble attitude; speaking with an Elder; etc.].

- Are there any resources or supports that would help you [or other scholars] more effectively develop these relationships?

- Do you regularly work with, consult or collaborate with any others as part of your research process? If so,

- Describe who you have typically worked with and how. [E.g. students, other scholars or researchers, research support professionals such as librarians, archivists or museum workers, other individuals or communities beyond the academy]

- Have you encountered any challenges in the process of working with others?

- Are there any resources, services or other supports that would help you more effectively develop these relationships?

Working with Data

- Does your research produce data? [e.g. interview transcripts, survey data, photographs] If so, what kinds of data are typically produced?

- Does your research involve working with data produced by others? [e.g. government data, datasets produced by other researchers] If so, describe what kinds of data you typically use and how you typically find that data. [e.g. research tools, techniques for discovery, specific individuals who help with locating the information]

If the participant works with data they produce themselves and/or by others, also ask:

- What are your plans for managing the data you work with beyond your current use (e.g. protocols for sharing, destruction schedule, plans for depositing in a repository or other external collection)

- Do you have conversations with Indigenous community members around determining data management protocols? [e.g. plans for retention, destruction and sharing; meta-data used to describe collections and their access]

- Do you engage in processes with any others around determining data management protocols? [e.g. librarians, data managers, other scholars]

- How do you incorporate the data you work with into your final research output(s)? [e.g. quotes, tables, models, data visualizations]

- Do you consult with individuals/communities around how this data is analyzed and incorporated into your research?

- Have you encountered any challenges in the process of finding or working with data?

- Are there any resources, services or other supports that would help you more effectively find or work with data?

Publishing Practices

- Where do you typically share your research in terms of scholarly publications?

- What are the main considerations for where you decide to publish your work in scholarly venues? [This could also include conference papers, in addition to journals, book chapters, books, etc.]

- Do you have conversations with Indigenous community members around developing outputs for publishing in scholarly venues? [e.g. co-authorship models, consulting on where to publish, seeking review and approval of content before seeking publication, starting up a new scholarly journal, etc.] If so, describe.

- Do you communicate with Indigenous community members/research participants around your activities publishing research in scholarly venues? [E.g. do you provide updates when your work is published, provide copies of your work] If so, describe.

- Are there any success stories about your research publications that you would like to share?

- Have you encountered any challenges in the process of publishing your research in scholarly venues?

- Are there any resources, services or other supports that would help you more effectively publish your research in scholarly venues?

- Have you ever made your research publications available through open access? [e.g. pre-print repository, institutional repository, open access journal or “gold” open access journal option)? If no, why not? If so,

- Where have you pursued open access publishing? What have been your motivations for pursuing open access? [e.g. required, for sharing, investment in open access principles].

- Do you have conversations with Indigenous community members to determine whether or how to make part or all of your research available via open access?

- Are there any resources, services or other supports that would help you regarding learning about or engaging with the concept of open access?

- Do you share your research beyond scholarly publications? [e.g. op-eds, books in the mainstream press, blogging]. If so,

- What are the main considerations for where you decide to share your work more widely?

- Do you have conversations with Indigenous community members to develop outputs for publishing in these venues? [e.g. co-authorship models, consulting on where to publish, seeking review and approval of content before seeking publication, etc.] If so, describe.

- Do you communicate with Indigenous community members about your publishing activity in these venues? [E.g. do you provide updates when your work is published, provide copies of your work] If so, describe.

- Have you encountered any challenges in the process of publishing your research in these venues? Are there any resources, services or other supports that would help you more effectively publish your research in these venues?

Scoping the Field and Wrapping up

- How do you keep up with your colleagues and the field more widely? [e.g. conferences, social networking]

- What future challenges and opportunities do you see for conducting research in Indigenous Studies?

- Is there anything else you think is particularly important for us to know about in terms of your experiences as a researcher that has not yet been covered in this interview?

- Do you have any other questions or comments about the interview or the research project before we conclude the interview?

Conclusion

- Thank the participant for sharing their knowledge and time.

- Acknowledge that the audio recorder is being turned off and turn off accordingly.

- Provide participant with the opportunity to ask questions and provide input beyond the formal interview.

- Share and discuss next steps in the research project including plans for the participant to review their transcript and the draft of the research report

Appendix 3. Select Bibliography

Andersen, Chris and Jean M. O’Brien, eds. Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies. Taylor & Francis, 2016.

Archibald, J. Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body and Spirit. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008.

Chilisa, B. Indigenous Research Methodologies. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2012.

Christen, K. “Relationships, Not Records: Digital Heritage and the Ethics of Sharing Indigenous Knowledge Online.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Studies and Digital Humanities, pp. 423-432. Routledge, 2018.

First Archivist Circle. “Protocols for Native American Archival Materials.” 2007. https://www2.nau.edu/libnap-p/protocols.html.

First Nations Information Governance Centre. “Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP).” 2014. https://fnigc.ca/sites/default/files/docs/ocap_path_to_fn_information_governance_en_final.pdf.

Deloria Jr., V. Red Earth, White Lies: Native Americans and the Myth of Scientific Fact. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 1997.

Drawson, A. S., E. Toombs, and C. J. Mushquash. “Indigenous Research Methods: A Systematic Review.” The International Indigenous Policy Journal 8, no. 2, 2017. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/iipj/vol8/iss2/5.

Goulding, D., B. Steels and C. McGarty. “A Cross‐Cultural Research Experience: Developing an Appropriate Methodology that Respectfully Incorporates both Indigenous and non‐Indigenous Knowledge Systems.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39, no. 5, 2016: 783‐801.

Kovach, M. Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations and Contexts. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Kurtz, D. “Indigenous methodologies: Traversing Indigenous and Western worldviews in research.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 9, no. 3, 2013: 217‐229.

O’Neal, J. “‘The Right to Know’: Decolonizing Native American Archives.” Journal of Western Archives, 6 no. 1, 2015: 1-17.

Overall, P. M. “Cultural Competence: A Conceptual Framework for Library and Information Science Professionals.” The Library Quarterly 79, no. 2, 2009: 175-204.

Porsanger, J. “An Essay about Indigenous Methodology.” Nordlit: Tidsskrift I Litteratur Og Kaltur 8, no. 1, 2004: 105‐120.

Smith, L. Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London and New York: Zed Books, 1999.

Stafford, J. R., R. Bowman, T. Ewing, J. Hanna and A. Lopez‐De Fede. Building Cultural Bridges. Bloomington, IN: National Educational Service, 1997.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). “Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.” https://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf.

Wilson, S. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Black Point, N.S: Fernwood Publishing, 2008.

Appendix 4. Project Engagements To-Date

Carrie Cornelius, Keahiahi Long, Michael Peper, Gina Petersen, Anthony Sanchez, and Kapena Shim. “Indigenous Inquiry: Seeking to Understand and Better Support Indigenous Studies Scholars on U.S. Occupied Institutional Land.” Panel session, ACRL 2019, Cleveland, OH, April 13, 2019.

Cody Fullerton, Kayla Lar-Son, Deborah Lee, and Desmond Wong. “Indigenous Studies Scholars in Canada: Recasting Narratives of Research Support in Academic Libraries.” ACRL 2019, Cleveland, OH, April 12, 2019. ACRL 2019.

Gina Peterson. “Collectors and Researchers: The Library & Indigenous Studies Explorations.” Presentation co-sponsored by Northwestern University Libraries and Northwestern’s Center for Native American and Indigenous Research (CNAIR). Evanston, IL. Feb. 13, 2019.

Deborah Lee, “Decolonizing Research: Conversations with Indigenous Scholars about Improvements to Library Supports: Voices from Canada.” Paper presentation. International Indigenous Librarians Forum, Waipapa Marae, Auckland, New Zealand. Feb. 7, 2019.

Kawena Komeiji, Keahiahi Long, and Kapena Shim. “Navigating Our Way Through the Research Needs of Hawaiian Studies Scholars.” Paper presentation. International Indigenous Librarians Forum, Waipapa Marae, Auckland, New Zealand. Feb. 7, 2019.

Danielle Cooper. “Working Towards Right Relationships: Perspectives from the Indigenous Studies Project.” Paper presentation. ACRL-NY Symposium 2018, New York, NY. Dec. 7, 2018.

Danielle Cooper, “Perspectives on the Limits of Assessment: Ithaka S+R’s Indigenous Studies Project.” Paper presentation. Library Assessment Conference, Houston, TX. Dec. 6, 2018.

Deborah Lee, Danielle Cooper, and Anthony Sanchez. “Decolonizing Library Research with Indigenous Methodologies.” Roundtable presentation. JCLC 2018: The Third National Joint Conference of Librarians of Color, Albuquerque, NM. Sept. 28, 2018.

Tanya Ball, Deborah Lee, Desmond Wong, Keahiahi Long. “Intersection between Academic Libraries and Indigenous Studies: A Qualitative Study to Improve Library Services for Indigenous Studies Scholars.” Panel presentation. JCLC 2018: The Third National Joint Conference of Librarians of Color, Albuquerque, NM. Sept. 27, 2018.

Endnotes

- Our previous projects in the Research Support Services program studied scholars in history, chemistry, art history, religious studies, Asian studies, agriculture, public health, and civil and environmental engineering. See: Jennifer Rutner and Roger C. Schonfeld, “Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Historians,” Ithaka S+R, Dec. 7, 2012, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.22532; Matthew Long and Roger C. Schonfeld, “Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Chemists,” Ithaka S+R, Feb. 25, 2013, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.22561; Matthew Long and Roger C. Schonfeld, “Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Art Historians,” Ithaka S+R, April 30, 2014, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.22833; Danielle Cooper et al., “Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Religious Studies Scholars,” Ithaka S+R, Feb. 8, 2017, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.294119; Danielle Cooper et al., “Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Agriculture Scholars,” Ithaka S+R, June 7, 2017, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.303663; Danielle Cooper et al., “Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Public Health Scholars,” Ithaka S+R, Dec. 14, 2017, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.305867; Danielle Cooper et al., “Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Asian Studies Scholars,” Ithaka S+R, June 21, 2018, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.307642; Danielle Cooper et al., “Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Civil and Environmental Engineering Scholars Ithaka S+R, Jan.16, 2018, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.310885. ↑

- Danielle Cooper and Roger C. Schonfeld, “Rethinking Liaison Programs for the Humanities,” Ithaka S+R, July 26, 2017, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.304124; Danielle Cooper and Oya Y. Rieger, “Scholars ARE Collectors: A Proposal for Re-thinking Research Support,” Ithaka S+R, November 28, 2018, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.310702. ↑

- It is important to also acknowledge how individual positionality informs the decisions behind the work undertaken at Ithaka S+R. In particular, I (Danielle Cooper) lead the Research Support Services program at Ithaka S+R. I came to the project with an academic background in Women’s Studies with a focus on grassroots LGBT libraries and archives, which gave me some understanding of non-hegemonic, social-justice informed research and information approaches, including in Indigenous contexts, but only enough to also know that undertaking a project at Ithaka S+R on Indigenous Studies would require relationship building and expertise far beyond what I had undertaken thus far in my work. A fuller reflection on my positionality related to this project can be found here: https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/a-new-project-on-indigenous-studies-scholars/. ↑

- It is important to recognize that defining Indigenous Studies is challenging, in part because there is no one Indigenous way of knowing. Having a working definition of Indigenous Studies that recognized this was an important part of the process of exploring how to develop this project. For the purposes of this project we use the term Indigenous Studies, which may also be referred to as Native Studies, Aboriginal Studies or First Nations Studies, among other terms (e.g. Hawaiian Studies), to refer to an interdisciplinary field focused on the histories, current experiences and futures of Indigenous peoples and communities. While research in the field may incorporate methods and theories from a variety of academic disciplines, at the field’s core is an underlying commitment to placing Indigeneity and Indigenous perspectives at the center of inquiry and pedagogy, including approaches to meaning-making, language, geography and knowledge production. Some work in Indigenous Studies is also undergirded by critical orientations, such as through commitments to decolonize pedagogy and research. At the institutional level, Indigenous Studies scholars are not only found within Indigenous Studies departments but also within and cross-listed between other departments such as agriculture, education, history, law, linguistics, medicine, nursing, political science, social work, sociology, and women’s studies, and many others. ↑

- Te Paea Paringatai (tribal affiliations to Waikato and Ngāti Porou) provided insight in her capacity as Chair of the International Federation of Library Associations and the Institutions (IFLA) Indigenous Matters Section. IFLA Indigenous Matters section endorsed the project and their ongoing support is appreciated, including their review of this report. Te Paea is also the immediate past president of the Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (LIANZA) and Customer Services Manager, Learning Teaching and Research at the University of Canterbury Library. ↑

- Camille Callison (Tahltan Nation) provided ongoing insight into the project including reviewing this report in her capacity as working on the Standing Committee for the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Indigenous Matters Section. Her insight is further informed through her work as the Canadian Federation of Library Associations’ (CFLA-FCAB) Indigenous Representative and Chair the CFLA-FCAB Indigenous Matters Committee and chair of the Truth & Reconciliation Committee. ↑

- Deborah Lee (who is of Cree-Métis, Mohawk, French, and Welsh ancestry) provided ongoing advice on the project as a recognized leader in and researcher on the field of Indigenous Librarianship. She provided an extensive review of the project’s methodology and ethics protocols, and to this report. The project also benefited greatly from her being a researcher on the University of Saskatchewan team. Deborah has been an incredible support and mentor throughout project. It has been a privilege for the researchers on the project to work with and learn from her. ↑

- Loriene Roy (Anishinabe; Enrolled: White Earth Reservation; Member: Minnesota Chippewa Tribe) provided preliminary insight into the viability of the project from her perspective as leader in Indigenous Studies. Loriene is a Professor at the School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin. ↑

- J. Kēhaulani Kauanui (Kanaka Maoli) provided preliminary insight into the viability of the project and thoughtful review of this report from her perspective as leader in Indigenous Studies. Kēhaulani is Professor of American Studies and Anthropology at Wesleyan University and one of the original six co-founders of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association. ↑

- In addition to the 11 academic libraries that participated in the research Simon Fraser University also contributed to an early phase of the project’s development. We thank Simon Fraser University for their contributions to the project. ↑

- See Appendix 3 for a select list of studies that were especially helpful to our thinking. ↑

- Margaret Kovach, Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations and Contexts (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 168. ↑

- In contrast, Western research typically positions the researcher as detached from the research subject with the position that distance leads to better insight for the researcher. This places the researcher in the privileged position of knowledge producer who extracts information from participants, which is problematic in a context where Indigenous contributions to knowledge traditionally have been stolen or obscured by Western researchers. Indigenous research approaches acknowledge that knowledge is created holistically and therefore put greater emphasis on the insight provided by the research participant and in dialogue between the researcher and the research participant. There is also attention given to how the audience of the research can make meaning by how the work is communicated and shared. See Bagele Chilisa, Indigenous Research Methodologies (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2012), 203-224. ↑

- This approach is in contrast to earlier projects by Ithaka S+R on research support needs in art history, history, and chemistry, where Ithaka S+R exclusively conducted the interviews that represented the bulk of the findings in the capstone reports. ↑

- Ithaka S+R also explored the possibility of including schools located beyond the US, Hawaiʻi, and Canada in the cohort. In order to develop further insight in how Indigenous Studies scholars’ practices vary in different contexts our exploration suggested that it would be worthwhile to develop a new project in the future that includes institutions from other geographic locales. ↑

- Each institution had flexibility in determining which research team members would be included in the project and how they would be included in order to best reflect their local needs. For example, the University of Kansas and Haskell Nations Indian University have an ongoing relationship through the library and decided to develop a team together. For further information about how each institution developed their teams, see the local reports (listed in Appendix 1). ↑

- We thank all of the teams that worked with us on the project. ↑

- We thank our hosts and those who contributed to the workshops locally. ↑

- Photos taken by Nikkole Kaylene Pirch. ↑

- See Appendix 4 for a list of engagements by project participants to date. ↑

- This approach diverges greatly from how Ithaka S+R designed projects with similar aims in the past. For example, for Ithaka S+R projects on art history, history, and chemistry, researchers at Ithaka S+R exclusively conducted the research and the sole output was a capstone report with recommendations for stakeholders. In the subsequent projects in religious studies, agriculture, Asian studies, public health, and civil and environmental engineering, Ithaka S+R partnered with cohorts of academic library research teams to conduct the research. However, Ithaka S+R also independently analyzed a sample of the collected data towards writing the capstone reports. In contrast, for this project Ithaka S+R only analyzed the publicly available local reports written by research teams towards developing the content for this report. Ithaka S+R and the research teams also did further work to ensure that the findings were not taken out of context by Ithaka S+R over the course of creating this report by a review process undertaken by the research cohort prior to publication. ↑

- There was no strict time limit on the interviews, and in some cases, the interviews exceeded 90 minutes. ↑

- The focus of these engagements were faculty as opposed to graduate students, in recognition that graduate students have a unique positionality as both scholars and students which warrants their own attention beyond a study of this scale. Due to the recommendations of the local faculty with which they sought to engage, some teams included a wider range of scholars beyond tenure-track faculty, including post-doctoral fellows and upper-level graduate students. ↑

- The interview guide was designed with considerable input from project advisor Deborah Lee, and we are grateful for her thoughtfulness and perseverance through multiple rounds of revision. ↑

- Chilisa, 203-224. ↑

- See Appendix 2 for the guide. ↑

- This iterative process of making meaning, which extends beyond the formal moment of the interview is reflective of how meaning is constructed over time by repeatedly reading, analyzing and writing toward increasingly refined understanding. See H.R. Bernard, Research Methods in Anthropology, 4th ed. (Lanham, MD: Altamira Press., 2006), 492. ↑

- We include this detail to highlight that when seeking to incorporate hospitality as a form of relationship building into research projects it may be necessary to secure funds and additional permissions. ↑

- While participation may include faculty who are of Indigenous or non-Indigenous backgrounds, Ithaka S+R advised that when possible, recruiting preference should be given to scholars who self-identify as Indigenous in recognition of ongoing under-representation of Indigenous perspectives in academia. This approach was developed through the initial advice of experts in Indigenous Studies and Indigenous librarianship who are acknowledged earlier in this report. ↑

- For example, the University of Toronto determined it would be important for an undergraduate Indigenous student to work on the project, and the University of Alberta and the University of Manitoba determined that some graduate students should be interviewed in addition to faculty members. It is important to recognize that this project was designed with faculty members as the primary participants. The research instruments were not designed for graduate students and we recommend that considerable adjustment be made to the interview guide in particular for those interested in developing projects with Indigenous Studies graduate students at the center of the inquiry. ↑

- See, for example, University of Toronto 5. ↑

- Haskell Indian Nations University/University of Kansas 6; University of Alberta 5; University of Saskatchewan 5; Northwestern University (personal communication on 3/20/2019). ↑

- University of Manitoba 3; Dartmouth College 6; University of Toronto 10; University of Hawaiʻi System 11. ↑

- University of Arizona 8; University of Manitoba 4-7 ↑

- University of Toronto 14; University of Arizona 5; University of Saskatchewan 17; University of Hawaiʻi System 11-13. ↑

- University of Toronto 16; University of Hawaiʻi System 33. ↑

- University of Saskatchewan 21-23; Haskell Indian Nations University/University of Kansas 21; University of Hawaiʻi System 29-32. ↑

- University of Hawaiʻi System 11-20. ↑

- Dartmouth College 7; University of Hawaiʻi System 14-15; Northwestern University 6. ↑