Transfer Pathways to Independent Colleges

Introduction

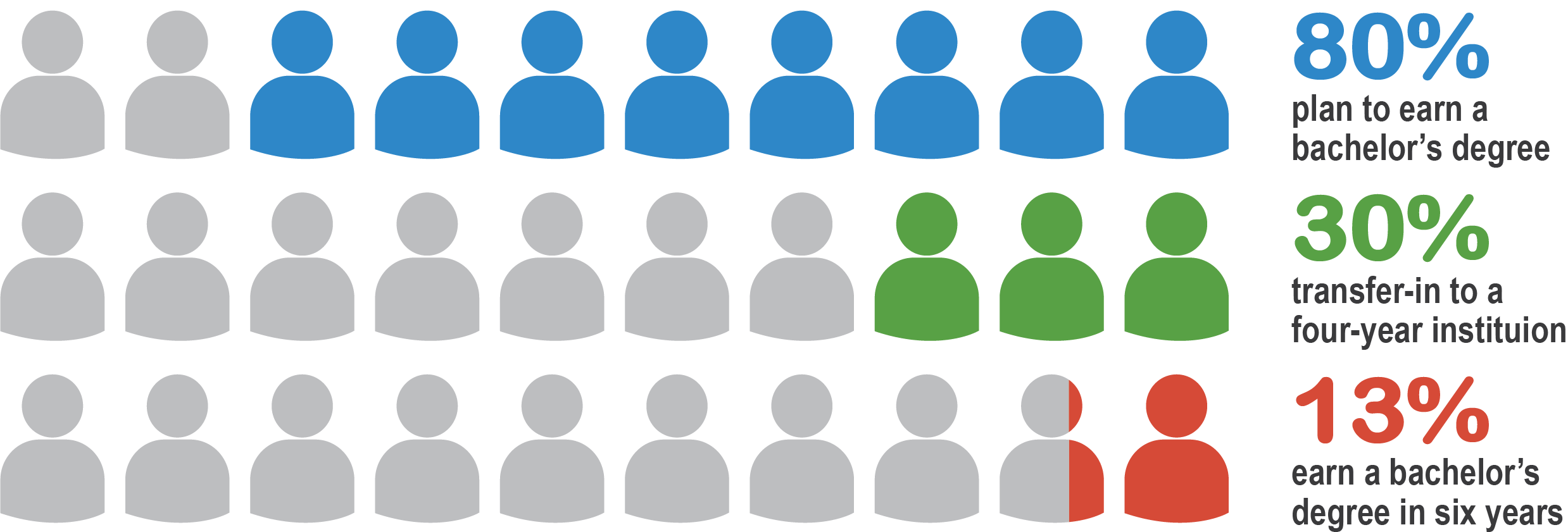

Every fall, an estimated one million American students begin their postsecondary education at community colleges.[1] In fact, close to half of all postsecondary students start off at these institutions—especially students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.[2] While most intend to eventually earn their bachelor’s degree,[3] less than a third transfer-in to a four-year institution and only 13 percent actually earn their bachelor’s degree in six years (Figure 1).[4] Transfer between two- and four-year institutions is a difficult pathway for students, leaving the well-documented benefits of earning a bachelor’s degree too far out of reach for too many.[5]

Figure 1: Community College Students’ Anticipated and Realized Bachelor’s Degree Completion

While this pathway has long needed repair, the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath highlight the urgency for innovation around community college to independent college transfer. COVID-19 is expected to produce an increase in community college enrollment due to students’ inability to safely travel further from home and families’ financial situations in the current recession.[6] As has been the case before the crisis, many of these students will be looking to transfer and earn their bachelor’s degree once the pandemic has passed. Meanwhile, independent colleges facing declines in fall enrollment will need to turn to local transfer students as a source of much-needed tuition revenue.[7] Streamlining the transfer pathway from public two-year and private four-year institutions will be critical both for the financial health of independent colleges and for the success of the increasing number of community college students pursuing a four-year degree.

Transfer from community colleges to the nation’s private nonprofit four-year colleges is an understudied and underutilized option for improving bachelor’s degree completion among traditionally underserved students.

In the last decade, a series of state, regional, and institutional policies have been developed to address this issue and improve the transition from two-year to four-year institutions. For example, the state of California’s Associate Degree for Transfer is intended to make it much easier for its community college students to transfer their credits to the state’s many public four-year schools.[8] At the institutional level, many schools have adopted transfer-friendly policies such as early registration, dedicated financial aid, and tailored orientation.[9] Understandably, the focus of these efforts has been largely within the public sector, as state policies have been passed to specifically address a more seamless transfer between public two- and four-year systems.[10] Transfer from community colleges to the nation’s private nonprofit four-year colleges, however, is an understudied and underutilized option for improving bachelor’s degree completion among traditionally underserved students.[11] In this report, we describe the opportunities that improving such a transfer pipeline can offer, the challenges and constraints to successfully improving this pipeline, and promising approaches to that end—including how individual institutions can draw on the power of collaboration to achieve impact at scale in their region. We focus specifically on transfer to independent colleges, which we define as private nonprofit, traditional baccalaureate institutions.[12] We close with recommendations for next steps and further research and provide a list of related resources (see Appendix A).

Opportunity for Alignment

At first, accepting two-year transfers may seem counter to the core features shared by many independent colleges, such as their relatively small student populations, their commitment to student engagement in campus life, and their predominantly full-time student enrollment.[13] Additionally, community college transfer students attending independent colleges have fared less well than native peers and transfer students attending public institutions. The literature and statistics on independent colleges, presented next, suggest that they hold notable but little-realized potential for promoting positive postsecondary outcomes for more community college transfer students. In that vein, establishing multi-institutional transfer pipelines between community colleges and independent colleges can offer valuable opportunities for both students and receiving institutions.

Although the term “independent college” is at times associated with elite private institutions that serve recent high school graduates in a residential setting, independent colleges are highly diverse in their make-up and offerings. For instance, like their public peers, independent colleges as a group offer degrees in a vast array of fields of study, enroll demographically diverse student populations, provide financial aid and institutional grants to students, and have robust student service programs. Many independent colleges have also explicitly designed or redesigned their offerings to better serve non-traditional students, for example through flexible programming, online coursework, and commuter-friendly practices. In addition to this, independent colleges tend to offer students unique opportunities for deep and meaningful engagement with faculty, the campus, and the broader community.[14] Because they outnumber public four-year institution,[15] independent colleges may also serve as viable alternatives for the many community college transfer students who prefer to attend a college that is closer to home. This is especially true for independent colleges located in what are otherwise “educational deserts” for community college students looking to transfer out.[16] However, many community college students are unaware of the benefits offered by independent institutions. Community college students looking to transfer choose public institutions in great numbers due to the assumption that a private college will cost more, which may not necessarily be the case.[17] With tailored financial aid for low income students, some independent colleges can be less expensive than a local public institution. The initial barrier of understanding that attending an independent institution is a viable option may prevent many community college students from attempting to engage the very institutions that could provide the aforementioned benefits.

Another important consideration is that independent colleges tend to have higher graduation rates than public colleges. For instance, the four- and six-year graduation rates of first-time students who begin their journeys at an independent college are 53 and 66 percent respectively, compared with 35 and 59 percent for their counterparts enrolled in public four-year institutions.[18] On the other hand, our analyses of a subset of public and private institutions indicate that independent colleges graduate their general transfer student population at lower rates than public colleges (by four percentage points), and at lower rates than their first-time students (by six percentage points).[19] These differences in outcomes are more pronounced when looking at students who transfer from community colleges specifically. Recent figures from the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) show that private nonprofit colleges, which enroll only 19 percent of all community college transfer students, graduate this student group within six years at a rate of 31 percent compared with 43 percent at public institutions.[20] This is despite the fact that community college students who transfer to four-year institutions of all levels of preparation perform, on average, the same or better than their peers who enrolled directly from high school or transferred from another four-year institution.[21] While these statistics do not account for differences in student characteristics and varied institutional resources, they suggest that independent colleges’ practices and policies may put community college transfer students at a particular disadvantage and can be improved (as we describe in the “Strategies for Realizing Opportunity” section of this report).

The literature thus suggests that there is a misalignment between community college transfer students’ needs and talents, and the policies and practices utilized by independent colleges. Not only are fewer independent colleges proportionally serving these students, but those that do are graduating them at rates below that of their public peers. However, despite this current trend, there is great opportunity for independent colleges to rethink how they serve community college transfer students.

One such opportunity is through liberal arts pathways. Pathways to the liberal arts would match independent colleges to community colleges transfer students in a manner that would benefit both students and the receiving institutions. In addition to offering a wide array of major fields of study in the arts and sciences, independent colleges often feature characteristics typical of the liberal arts experience, such as small cohort and class sizes, courses with seminar paper assignments and group work, and robust extracurricular activities. Other common features include intimate classroom environments that facilitate student discussion on different viewpoints, out-of-class discussions and engagement with faculty, experiential learning opportunities that expose students to global diversity, all of which encourage a commitment to learning post-graduation.

Research also points to long-term financial benefits of liberal arts majors, despite popular preconceived notions about the economic utility and earnings potential of pursuing a liberal arts degree.[22] Employers in today’s labor market are increasingly valuing skills such as abstract problem solving, critical thinking, and effective communication—skills that are strongly emphasized in liberal arts colleges and programs.[23] For example, analyses of self-reported data on LinkedIn between 2010 and 2013 show that liberal arts majors have entered the technology workforce at greater rates than computer science and engineering majors, taking on a variety of different roles in that industry.[24] The growing demand for “soft” skills such as these means that students who transfer-in to independent colleges—and successfully complete their degree—may see an increased return on their college education as they are desired by employers in a variety of fields. Researchers believe this trend will only grow over time as the labor market evolves: “Employers are and will continue to be looking for candidates with emotional intelligence, excellent communication skills, intellectual agility, a strong grasp of initiative, and a sense of ethics. The nimble and agile thinkers needed for the future depend on the very skills liberal arts programs cultivate in their students.”[25] In fact, a cross-sectional survey of 1,000 college graduates found that those with a liberal arts education were more likely to be leaders in their careers and communities, more likely to report feeling fulfilled in their lives, and were even more likely to be altruistic.[26] Studies are currently in progress to research the positive health and well-being outcomes of liberal arts graduates as well.[27]

These lifelong benefits should not be reserved only for well-resourced students and should be intentionally extended to those who have been historically excluded from liberal arts colleges: namely those who start their higher education at community colleges, which enroll a large share of students of color, first-generation learners, and students from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. Half of all minority students start their higher education at a community college.[28] Similarly, two-thirds of community college students are in households at the bottom half of the national income distribution,[29] and the majority of first-generation students begin their education at two-year institutions.[30]

Even beyond the argument for equity, the potential for a match between community college transfer students and liberal arts oriented independent colleges is made more compelling when looking specifically at historical trends in humanities and liberal arts coursework completion. While the share of bachelor’s degrees conferred in the humanities and liberal arts has decreased in recent decades, the share of associate degrees in these disciplines has increased.[31] Additionally, two-year students complete as much liberal arts coursework as four-year students prior to transferring, and all students who complete associate’s degrees, irrespective of the field, fulfill significant required coursework in the humanities and liberal arts. Recent figures from the Community College Research Center also confirm that humanities and liberal arts coursework completion at the two-year level predicts students’ bachelor’s completion, suggesting these students may perform especially well once admitted.[32] As such, many students transferring from community colleges, a share of whom may fill increasingly empty seats in liberal arts programs, are well-matched to a transfer pathway into an independent college with a liberal arts focus.

Lastly, independent colleges themselves may have a strategic need to enroll more community college transfer students. National high school graduating classes are becoming smaller each year, which limits the recruitment pool for all US colleges alongside shrinking international student enrollment.[33] Targeting adult learners will need to be a focus for independent colleges in the next decade, especially for small independents that have been historically dependent on recruiting local 18-24 year old populations.[34] The national “birth dearth” renders the reliance on traditional-age student enrollment an untenable recruitment strategy; enrolling transfer students from community colleges—where the average age is 28 years old—is especially promising because it targets a different demographic.”[35]

This logic has yet to translate to a change in strategy at scale. A recent survey of more than 400 independent college leaders found that most utilize transfer students, be it from two- or four-year colleges, merely to fill gaps in their admissions targets. Respondents did note, however, that admitting community college transfers specifically could help them reach their strategic plans around diversity.[36] Independent colleges can greatly improve upon their mission of providing equitable access to quality education by improving their community college transfer initiatives to help fill this troubling gap. Of course, the financial implications and considerations for recruiting and supporting students with higher levels of need are significant and complex; we discuss these in a later section of this report and focus next on strategies for realizing the opportunity to better align community college transfer students and independent colleges.

Strategies for Realizing Opportunity

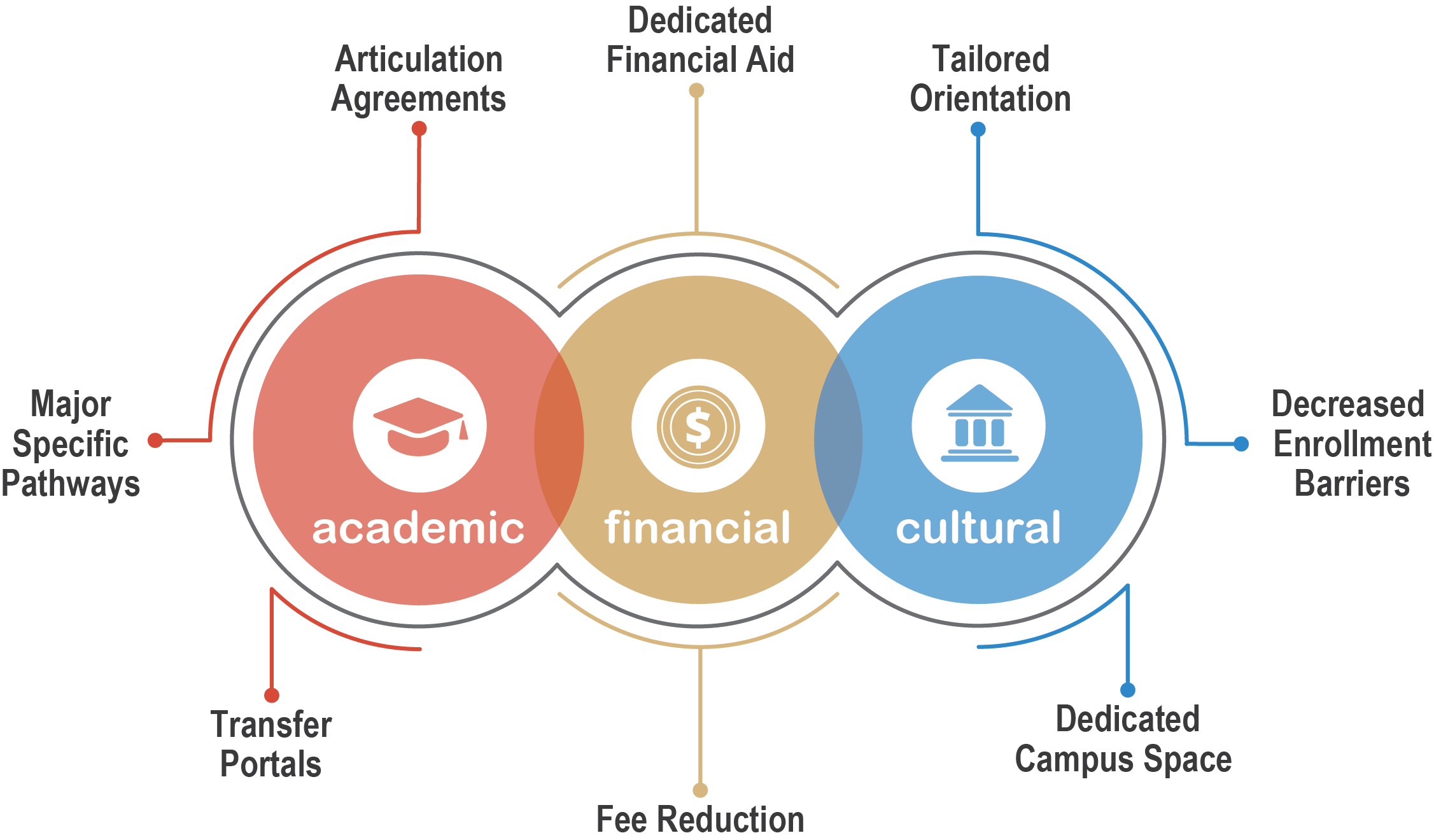

This section discusses specific challenges that impede both access and completion for community college transfer students pursuing their bachelor’s degree, as well as key strategies for independent colleges to eliminate these barriers. It does so by grouping strategies into three areas of practice for realizing the opportunity around community college to independent college transfer: academic, cultural, and financial (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Strategies for Improving Community College Transfer-In and Completion

Academic Dimension of Transfer

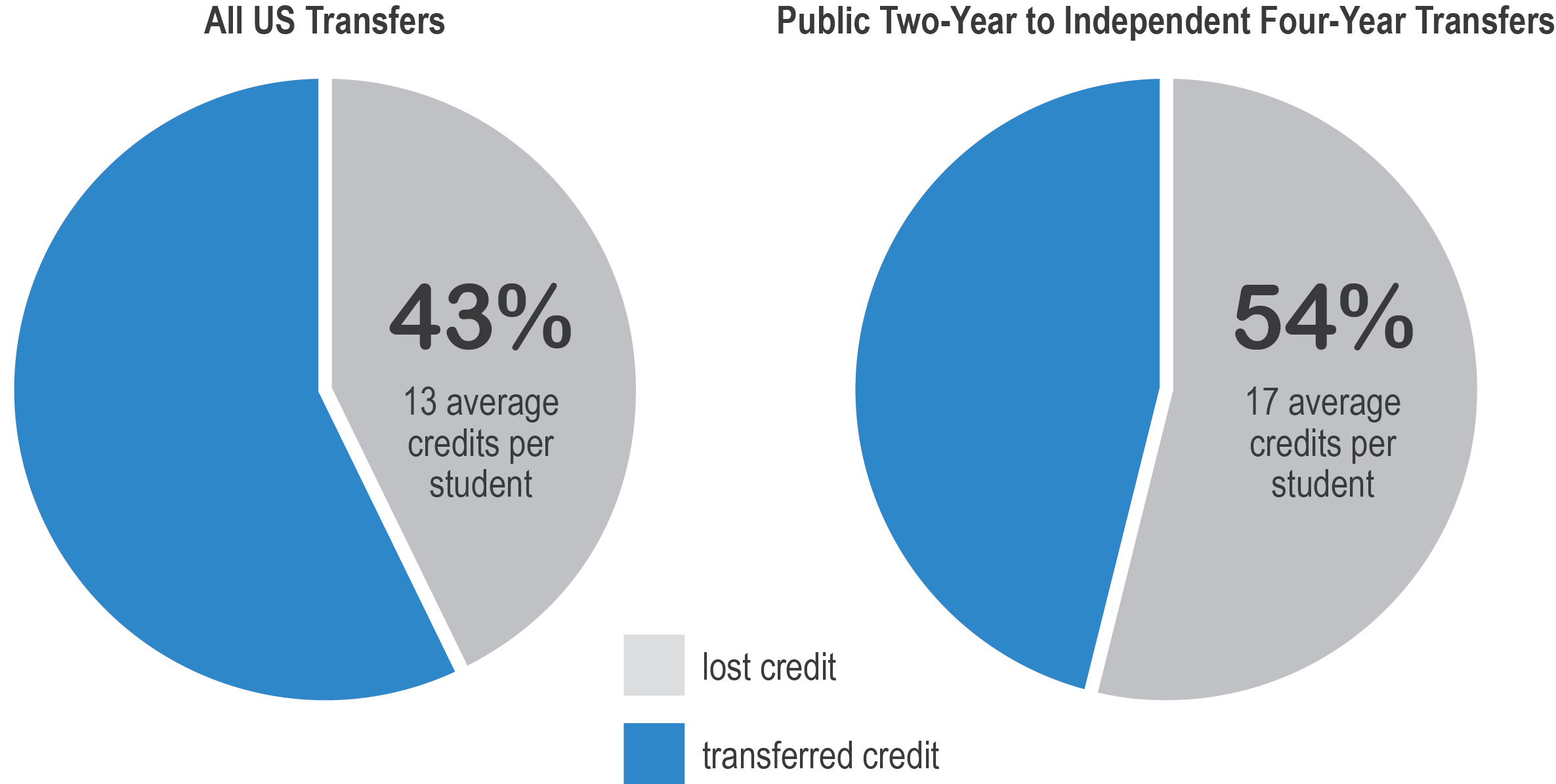

The top barrier for successful transfer among community college students, i.e. baccalaureate completion, is poor credit transfer between institutions. Studies have shown not only the widespread loss of credits occurring when students transfer from two- to four-year institutions, but also the causal relation this has on bachelor’s degree completion. To quote one such study, “the greater the loss, the lower the chances of completing a BA.” In fact, community college students who have most or all of their credits transferred are 2.5 times more likely to graduate with their bachelor’s degree when compared to those who have less than half of their credits transferred.[37] However, according to a 2017 study by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) analyzing Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study data, students lose roughly half (43 percent) of their earned credit when they transfer. This accounts for about 13 credits per average transfer student, or almost a full semester’s worth of coursework. This loss of credit is worse for those making the transition from public two-year colleges to private nonprofit four-year colleges (which accounted for 9 percent of transfers in the GAO study): Here, the average credit loss was 54 percent, or 17 credits (Figure 3).[38]

Figure 3: Percent of Average Credit Lost During College Students’ Transfer

Nontransferable, excess credits plague the community college to bachelor’s degree transfer trajectory, and much of this is due to cafeteria-style approaches that leave entering two-year students lost in a confusing maze of course selection. With too many choices and too little information, students intending to eventually transfer to four-year programs end up making haphazard choices that do not align to their educational and career goals. Often, cafeteria-style community colleges struggle with adequate resources to advise students; estimates put the median advisor to student ratio at 1 to 441.[39] An overwhelming barrier to transfer is the lost credits, time, and money resultant from unnavigable pathways toward the degree that lead to uninformed curricular missteps. To tackle this, a number of community colleges are designing guided pathways, or highly structured program maps with specific support systems, to help community college students plan coursework based on the program they would like to pursue at a four-year institution. Independent colleges can build on this effort by designing major-specific pathways of their own, as we show later in this section.

While many community colleges have made it easier for students to efficiently transfer credit, various policies and practices at independent institutions have made it more difficult. Faculty, even at colleges that claim to accept transfer credit, are often reluctant to replace their own course with a similar course taught at the community college level.[40] This can lead to extensive repetition as community college students are forced to retake classes. Even when courses are accepted, some institutions only accept transfer credit as elective credit, delaying students’ progress towards their degrees.[41] Another factor that can lead to excess credit is the requirement that students take a minimum number of credits at the four-year institution.[42] All these policies, while well-intentioned, can prevent community college students from effectively and efficiently transferring credits and completing their degrees.

What solutions have independent colleges employed to approach the burdensome challenge of credit loss and excess credit? They are divided into three particularly promising types of strategies, which we discuss in greater detail in the sections that follow: articulation agreements, major-specific pathways, and transfer portals. We focus our discussion of these three academic policies at the consortium-level specifically. This model of practice is especially promising for independents, as such collaboration can deliver credit transfer at scale. Another reason to partner with neighbor institutions is that transfer students are likely to remain in the same state and region as their community college.[43] By making an entire group of independents more transfer-friendly, the sector can establish itself as a visible and viable option for potential transfer students in the region. There is also an administrative case for establishing consortium-wide articulation agreements. Often, a major barrier to articulation at independent schools is registrar offices’ struggle to relinquish control over which courses transfer from the community college. Managing transfer applications is also a burdensome challenge for many institutions, as the different systems involved do not always align with each other nor adequately reflect students’ experiences. Crafting consortium-wide articulation agreements can encourage institutions to accept courses that have already been approved by their peers and streamline transfer applications, making community college students’ credit transfer process more effective and efficient for both parties. Additionally, when transfer-driven policies are adopted by a group of institutions and maintained by the consortium as a whole, individual institutions are more likely to change their culture to support community college transfer.

Articulation Agreements

Articulation agreements between two- and four-year institutions are the first line of defense against credit loss and excess credit. We specifically recommend shared contracts between community colleges and independents that guarantee the block transfer of coursework as well as junior-level status. This alleviates the burdensome, labor-intensive process of individual course-to-course equivalency and the related course evaluation process, which often involves department chairs, faculty, registrars, and other administrative personnel. Articulation agreements that transfer course sets and recognize junior status for associate degree earners are especially important strategies for private nonprofit colleges, which put an undue burden on their two-year transfer students. For example, the Council of Independent Colleges (CIC) recently found that only one-third of its member institutions accept associate degree holders as juniors, and 78 percent require additional general education coursework for transfer students holding an associate degree.[44]

We can look to North Carolina’s private nonprofit colleges for an example of how to do this effectively. In 1996, and most recently revised in 2015, the North Carolina Community College System entered into a comprehensive articulation agreement with North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities (NCICU), which now includes 30 signatories. The ultimate goal of this agreement is “the seamless articulation from the community college to the NCICU institution with minimal loss of credit or repetition of work.” This direct collaboration, which is consistent with articulation agreements between the North Carolina Community College System and the University of North Carolina system, allows two-year students the same transfer guarantees as at state four-year institutions.[45] The agreement ensures junior-level status for associate degree earners, and the associate degree itself transfers as a unit that meets all general education requirements.[46]

Similarly, the Illinois Articulation Initiative (IAI) is a statewide transfer agreement with which all public two- and four-year institutions are required to participate. However, the articulation agreement utilized by IAI does not require the completion of an associate degree. Instead, all 100+ participating colleges agree to offer and/or accept the IAI General Education Package, a bundle of 12 courses conferring “37-41 semester credit hours for a full complete transferable general education package.”[47] Instead of creating a separate agreement, 49 independent Illinois colleges participate in IAI.[48] A compelling example of how a statewide agreement can be capitalized upon by independent colleges to improve transfer outcomes comes from Elmhurst College. Elmhurst has been accepting the general education package from IAI for several years and has also developed a number of 2+2 and other articulation agreements with local community colleges. Elmhurst has established additional strategies for recruiting and supporting community college transfer students that, as is discussed below, are necessary complements to the academic aspect of transfer pathways.[49] Participating in IAI and dedicating supports to transfers appears to have helped Elmhurst improve its transfer student recruitment and graduation. According to our analysis, Elmhurst increased its transfer-in rate by eight percentage points between 2012 and 2017, and achieved a transfer bachelor’s completion rate of 79 percent, over one-and-a-half times the US four-year average (47 percent).[50]

Other independent consortia that have implemented or are implementing articulation agreements with state and regional community colleges include (but are not limited to): Alabama Association of Independent Colleges and Universities’ 2 to 4 Transfer Program; New England Board of Higher Education’s New England Independent College Transfer Guarantee (in progress); Georgia Independent Colleges Association’s Transfer Articulation Agreement with the Technical College System of Georgia; Independent Colleges and Universities of Florida’s Articulation Agreement with the Florida College System; Michigan Independent Colleges & Universities’ participation in the Michigan Transfer Agreement; Oregon Alliance of Independent Colleges and Universities’ participation in the Oregon Transfer Module; and Association of Independent California Colleges and Universities’ Associate Degree for Transfer Commitment. We discuss the latter in more detail in the next subsection.[51]

Major-Specific Pathways

While shared articulation agreements that both ensure the block transfer of core curricula and grant community college students junior-level status are necessary first steps to be taken by independent colleges and universities wishing to boost their two-year transfer-in and graduation rates, articulation agreements alone will not navigate these students toward the degree. As described previously, cafeteria-style approaches to the first years of postsecondary education may move students toward junior year status, but without the proper coursework needed to complete a specific major.

Both public and private universities are joining in state efforts to standardize major-specific pathways. Major-specific pathways are guides shared early in two-year students’ education that clearly map course requirements, sequences, and prerequisites for completing the degree within a specific field of study. These guides are imperative for helping transfer students—even those who transfer-in to a four-year institution as a junior with a core package of articulated general education coursework—reduce the time and financial burden of excess credit. These pathways are especially important in the natural sciences, where students are expected to make lock step progression in lower division courses to be ready for upper-division major coursework. Major-specific pathways promise to offset the inflated national average for excess credit, which amounts to 16.5 credits per bachelor’s degree graduate.[52]

California has led the charge in many statewide transfer initiatives, and the Association of Independent California Colleges and Universities (AICCU) has ensured its member institutions provide transfer options comparable to the state’s public universities.[53] Currently, 40 AICCU members participate in the Associate Degree for Transfer (ADT) Commitment, the private sector adaptation of the state ADT pathway, which guarantees two-year graduates junior standing in one of 36 approved ADT majors upon completion of the ADT degree (22 of these majors being in the traditional liberal arts and sciences).[54] Each major pathway is clearly mapped out for community college students. For example, a student preparing for an ADT in psychology at San Diego Mesa College—a degree accepted by 30 independent California colleges—is given clear guidance pertaining required learning outcomes, mandatory grades per required 60 units, and applicable coursework from the community college’s menu of psychology offerings that can be taken to satisfy the fully articulated baccalaureate degree.[55]

Another state that has implemented major-specific pathways is Washington. Washington outperforms others in several key transfer metrics, including community college transfer-in bachelor’s completion rates at private nonprofit four-year institutions. Its independent colleges graduate community college transfer students at a rate that is 15 percentage points higher than the national average.[56] One of its innovations is well-researched major-specific pathways in addition to articulation agreements that ensure credit earned is transferred and applied to baccalaureate requirements efficiently. The Direct Transfer Agreement associate degree (DTA) and the Associate Science-Transfer degree (AS-T) guarantee recipients the block transfer of 90 credits and junior class standing. Within both degrees, there are ten Major Related Programs (MRP), which “prepare students for bachelor’s degrees in specific majors.” Importantly, every MRP contains “a course plan based on the DTA or AS-T degree…Four-year schools that sign an MRP are agreeing that the MRP prepares students for that major at their school.”[57] This includes signatory independent colleges; currently eight of ten of the Independent Colleges of Washington members accept either the DTA or AS-T degree, and many also participate in major-specific pathways provided by MRPs.[58] The results of this implementation speak for itself: Washington’s State Higher Education Coordinating Board found that while MRPs did not eliminate excess credit altogether, two-year transfers following an MRP graduated from four-year schools with 11 fewer excess credits than those who did not follow any transfer agreement, and eight fewer excess credits than those who followed a major-independent, general education-based articulation agreement.[59] Other independent consortia that utilize major-specific pathways include Michigan Independent Colleges & Universities’ participation in the MiTransfer Pathways program and Tennessee Independent Colleges and Universities Association’s participation in Tennessee Transfer Pathways.[60] As a complement to their work on general education block articulation, NCICU is developing discipline-specific agreements in psychology and sociology.[61]

Transfer Portals

Transfer portals are online tools that assist student and institution alike in that they leverage information from articulation agreements and major-specific pathways to automate the transfer of bundled coursework in a transparent fashion. This is an especially helpful technology for independent schools in that many potential transfer-in students do not think their community college credit will count toward a private school degree, and for many two-year transfer students, the course articulation process remains a daunting black box. Being able to see how and where two-year students’ specific earned credit will transfer can open up doors they never knew existed.

New Jersey’s online transfer tool, NJ Transfer, provides free transcript evaluations and course matches between participating community colleges, public four-year institutions, and independent colleges. Nearly all of the institutions in the Association of Independent Colleges and Universities in New Jersey (AICUNJ), and all of the state’s CIC members, have submitted course information to NJ Transfer and have determined which courses from each of the state’s 25 participating community colleges will be accepted for certain credits.[62] The tool allows community college students to see which of their courses will transfer to the state’s four-year institutions and whether they will be accepted for general education credit. New Jersey’s prioritization of transfer initiatives in recent years has seen positive results: According to our analysis, in 2016-17 the state ranked in the top 12 in terms of average bachelor’s completion rate for all transfer-in students at independent colleges.

Another independent consortium that has adopted a transfer portal is the Independent Colleges and Universities of Texas’ (ICUT) Texas Pathways,[63] which “[connects] associate degree-earners with the most transfer-friendly degrees at private, nonprofit colleges and universities.”[64] Rather than adopting or being integrated into an extant public portal, the ICUT Foundation received a National Venture Fund grant from the Council of Independent Colleges to develop an extension of an academic sharing platform called Acadeum.[65] The resultant Texas Pathways portal matches ICUT members’ curricula to coursework offered by the Texas Association of Community Colleges. It also caters to two-year transfer students interested in an online distance-based program, featuring more than 60 online degrees from ICUT institutions. This is innovative in that many community college students, as we shall see in the next section, do not have the ability enroll as full-time, on-campus students due to various work and family responsibilities. ICUT’s transfer portal not only securely accesses community college users’ academic records but also their financial aid data, which allows potential transfers to see the net cost and completion time for their chosen degree online before even applying to their choice four-year college.[66] North Carolina is following Texas’ lead: NCICU recently announced that it is using the same funding source employed by ICUT to create the North Carolina College Completion Portal, which will build off the consortium’s articulation agreement described earlier in this section.[67]

Cultural Dimension of Transfer

While state-, regional-, and consortium-level academic policies are key to driving two-year transfer students’ enrollment in and graduation from four-year colleges, they must be accompanied by institution-level practices that support the specific needs of students coming from community colleges to independent institutions.

Independent colleges can be especially difficult environments for community college transfers. For example, the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation recently surveyed a sample of high-achieving, low-income transfer students. It found that 92 percent of these students found it challenging to manage the workload of their new four-year institution; 20 percent even considered dropping out of their school because of these challenges, despite 93 percent holding a B or higher grade point average.[68] As another study on this “border crossing” notes: “The cultural and social complexities” students experience while moving “from the open-access working-class setting of community colleges to the exclusive privileged setting of liberal arts colleges and research universities” are profound.[69] This holds true for non-elite institutions as well. A study sampling 216 two-year students who transferred into one of two private liberal arts colleges (each with acceptance rates above 65 percent) found that the total sample experienced “transfer shock”—the cultural disorientation of a student post-transfer that is often quantified by a momentary dip in grades—with an average GPA decline of 0.09.[70]

Researchers have been writing about transfer shock since the 1960s.[71] This temporary yet challenging state stems from the vast difference in campus pedagogies, workloads, and environments, and can be a major barrier to post-transfer success for students matriculating into four-year institutions. This is can be especially true for community college transfers, a population that disproportionately consists of low income, first-generation, and underrepresented minority students.[72] Such student groups have gained access to higher education only in the last half of the twentieth century,[73] and thus have less awareness that crossing the cultural border to a baccalaureate institution is a possible (and fruitful) move. This section looks at three specific interventions for supporting these students during their cultural transition into an independent four-year institution: tailored orientation programming, decreased enrollment barriers, and dedicated campus centers.

Tailored Orientation Programming

The lack of onboarding for transfer students at four-year institutions is a major impetus for transfer shock, exhaustion that hinders student persistence and can even lead to students withdrawing from the college altogether. In general, orientations are less available on four-year campuses for transfer students than they are for incoming first-year students, and those that are offered are typically pared-down versions of the first-year orientation. These onboarding events do not meet the needs of incoming transfer students, who have different challenges than do first-time students. Notes one scholar, “to improve transfer viability, transfer education must go beyond the search for academic parallelism in freshman and sophomore studies at the two- and four-year levels by including intellectual, social, and cultural preparation for the baccalaureate environment.”[74] In a survey of more than 400 four-year private colleges, only 45 percent noted that they offer tailored orientation for transfer students. Additionally, more than half of the respondents noted that they neither offer orientation nor ongoing support for students who transfer-in to their institutions.[75] Experts recommend tailored transfer orientations that focus on things like developing appropriate first semester schedules based off students’ majors and educational goals, delivered in formats that promote personalization and connection-making (e.g. small group workshops).[76] To accommodate transfers’ schedules, supplementing these events with virtual bridge programs can also offset disorientation.

One university taking steps to ensure transfer students feel welcome is Madonna University, a private university in Michigan. Madonna has a Transitions Center dedicated to guiding and supporting transfer and other nontraditional students throughout their time at the university. As part of their programming, the Transitions Center hosts an “Adult and Transfer Student Orientation” that can be completed either in-person or online before classes start in late August. The program introduces transfer students to the university’s available resources and offers them an opportunity to connect with one another the way native students would during their summer orientation.[77] During the year, the Transitions Center provides a wide variety of programming to support the needs of transfer students including success coaching, student meet-and-greet events, and even a “Transfer Student Appreciation Day” in April.[78] University-level supports for transfer students at every point in their college career starting with orientation are critical for these students to feel welcome, and enables their success at the four-year institution.

Another institution that has developed onboarding materials specifically for transfer students is King University in Tennessee. Rather than simply direct transfer students to a brief orientation, King offers a yearlong seminar specifically for transfer students similar to the “First-Year Seminar” provided for incoming native students. The “Transfer-Year Seminar” focuses on academic skills and engagement with campus life and provides strategies for making the most of one’s transfer experience.[79] The small size and structure of the course also allow for personalized attention to each transfer student enrolled. Targeted supports for transfer students throughout the year are key to supporting students making the leap from two- to four-year institutions and serve as models for other independent colleges pursuing this pathway.

Decreased Enrollment Barriers

Two barriers during the enrollment process contribute substantially to transfer shock: required developmental coursework and delayed course registration. While the following two examples given for decreasing these enrollment barriers are being practiced at public four-years, independent colleges should take note and follow their example.

Most students in developmental (or remedial) coursework do not graduate; in fact, students who take developmental coursework at four-year colleges are 20 percentage points less likely to earn their bachelor’s degree (35 percent estimated to graduate in six years) when compared to the national share of bachelor’s graduates (56 percent estimated to graduate in six years). Across the board, Black, Latinx, and low income students—subgroups that are disproportionately represented within the population taking the two-year to four-year transfer pathway—are more likely to be placed in gateway developmental programs, blocking their access to credit-bearing coursework, and ultimately, the degree.[80] This process of remediation is especially debilitative for community college students pursuing the bachelor’s degree at independent institutions: A recent survey of CIC member institutions found that more than three-fourths of participating institutions required transfer students who already hold an associate degree to take additional general education courses, 10 percent of which were at the developmental, noncredit-bearing level.[81] Corequisite remediation can help students progress toward the degree in a timely manner and reduce the transfer shock that leads to high dropout rates. In this model, students who do not meet college readiness criteria still enroll in college-level coursework and are provided with additional instruction and support. Tennessee’s innovation in corequisite education has shown promising results. After the Tennessee Board of Regents converted to an exclusively corequisite model, the pass rate for gateway courses rose from 12 to 63 percent, meaning that five times more students now complete their developmental education due to the policy change.[82]

Similar to this enrollment hurdle for transfer students is delayed course registration. Often, native students—even first-years—are granted earlier registration access than transfer students; “the result,” one study critiques, is that “transfer students are ‘welcomed’ to the university with a long list of closed classes.”[83] This institutional barrier makes inaccessible the specific courses that transfer students need to progress toward the bachelor’s degree, leaving them in a curricular limbo. Western Michigan University has taken proactive steps not to punish its transfer students in this way. It uses a registration system that gives priority to students based on the number of credit hours completed. Transfer students who have completed their application materials early are then included in the priority registration dates based on the number of transfer credit hours they have completed. For example, someone transferring in with 60 credit hours would register for classes at the same time as a junior.[84]

Dedicated Campus Space

Providing an on-campus “home” for transfer students greatly helps inoculate against transfer shock.[85] Such a “one-stop service center” or transfer office might include academic advising services, financial aid office hours, or other student supports tailored specifically for transfer students. A full-service transfer office would provide a dedicated base for transfers, many of whom might need an area to work from while commuting to campus, and create a sense of community among transfer cohorts. Holding peer mentoring at these spaces is especially recommended; these mentors can not only help incoming transfer students navigate their new campus, but also “help demystify the transfer process and inform and motivate prospective students.”[86]

While many large public universities have dedicated specific campus space and supports for transfer students, this practice is less common among private colleges. One example of a small, independent school creating campus space for transfers is D’Youville College in New York. D’Youville consistently has transfer students compose around 50 percent of its incoming class and has allotted an office in its Student Success Center specifically for these students. The Transfer Services office is a one-stop shop for transfer students; the office provides program-specific academic advisors as well as career and other related supports. Each transfer student is assigned a student success team that consists of a traditional academic advisor, a faculty mentor, and a career coach.[87] Not only are transfer students receiving the same level of support as traditional students, but they are also provided transfer-specific materials to help them navigate the transition from their previous institution to D’Youville. These institution-level supports for transfers can be integrated into the traditional liberal arts support system and should become commonplace at other small, independent schools.

It should be noted that dedicated campus space for transfer students can include resources that serve their families, too. Almost half (47 percent) of the seven million US community colleges students enrolled in credit-bearing coursework are 22 or older, the average age being 28. Community college-enrolled adults are students with complex work and family duties, and 15 percent of students enrolled in public two-year colleges are single parents.[88] These students rarely receive adequate support for these unique responsibilities such as on-campus childcare. One institution working to remedy this is Stockton University in New Jersey. Stockton consistently has transfer students compose around 50 percent of its incoming class.[89] The university provides a wide variety of resources for transfer, low-income, and commuter students including transfer-specific housing with resident assistants trained to help transfer students with the unique problems they face on campus. Stockton has developed several programs to support the needs of nontraditional and commuter students such as an early childcare center, a discounted meal plan for commuters, and even a student-run organization that coordinates on-campus events for commuter students to ensure they feel integrated into campus culture. Tellingly, Stockton’s transfer-in bachelor’s completion rate was 74 percent in 2016-17, two percentage points higher than its bachelor’s completion rate for first-time students Such figures indicate that adopting dedicated campus space for both students and their families is a recipe for success, both for the institution and its students. Other transfer-centric practices, such as establishing strong two-year and four-year faculty relationships, are detailed in the “Recommendations and Next Steps” section of this report.

Financial Dimension of Transfer

Unmet financial need remains a major barrier for students wishing to make the transition to a baccalaureate institution. This is especially true for independent colleges, which carry high sticker prices that many two-year students regard as being out of their price range. Although independent colleges provide about three times more grants to students than public universities and almost six times more financial aid,[90] many community college students—despite their high need on average—have little experience securing such funding. And even if funding is secured, net prices can nonetheless remain out of reach.

Independent colleges’ financial strategies will be greatly shaped by the specific academic strategies they choose to incorporate as they develop their community college transfer initiatives.

Complex financial aid systems are especially challenging for socioeconomically disadvantaged and first-generation students who are unfamiliar with the FAFSA, have limited access to the necessary information required by the form, or might not even be aware of their eligibility for financial aid.[91] Community college students in particular, including Pell-eligible students, are less likely to apply for aid than students enrolled at four-year institutions.[92] They also may have exhausted their personal and financial aid funds before having the opportunity to enroll in a four-year institution. These financial aid behaviors greatly affect likelihood of transfer and persist even after students transfer to four-year institutions. A 2005 study, for example, found that for every $1,000 increase in four-year tuition over two-year tuition, the probability of transfer decreases by almost three percent.[93] The lack of portable aid for those who were able to navigate the financial aid process at their community college, and the fact that transfer student acceptance letters are sent after financial aid application deadline dates have passed, create additional challenges.[94]

This section looks at two strategies individual institutions can take to address the financial challenges of community college transfer students: dedicated financial aid and fee reduction. It is important to note here that independent colleges’ financial strategies will be greatly shaped by the specific academic strategies they choose to incorporate as they develop their community college transfer initiatives. In that vein, a discussion of the financial implications of admitting and supporting community college transfers students more broadly is presented in the “Recommendations and Next Steps” section of this report.

Dedicated Financial Aid

Independent colleges can help recruit and graduate more community college students by creating specific financial aid funds and policies for this unique segment of transfer students. Many researchers and practitioners recommend that independent institutions consider redeploying institutional aid to support transfers.[95] In fact, private institutions typically award less needy students with more financial aid funds than needed.[96] Based on a federal formula, institutions have awarded students from families earning $155,000 annually with an additional $5,800 per year on average. Institution-, consortium-, and even state-level grants and scholarships that are awarded to community college students looking to transfer to independents could be especially promising for building the community college to independent college pathway. Additionally, financial planning and advising should accompany aid as part of the recruitment process and be offered throughout transfer students’ tenure at the independent institution. Schools might consider, for example, dedicating a financial aid officer to help community college students navigate the complex financial aid process, ensure that they are applying to all applicable scholarships and grants, and field any questions that arise during the process.

Neumann University in Pennsylvania, for example, offers scholarships solely for community college transfers with a maximum yearly award of $13,000. Scholarships are tiered by community college cumulative GPA with even the lowest GPA group receiving a yearly scholarship of $9,000. Neumann also makes an effort to ensure that financial aid information is available the moment a potential transfer student steps on campus. Potential transfer students get a tour of campus and immediately sit down with admissions counselors and financial aid counselors to discuss program-specific requirements and determine the feasibility of paying for a bachelor’s degree at Neumann. This level of transparency and financial assistance for community college transfer students can and should be replicated elsewhere if liberal arts and small independent schools wish to successfully recruit and graduate students from these populations.[97]

Fee Reduction

Financial aid does not solve all transfer students’ unique monetary challenges. According to the College Board, tuition and fees for private four-year colleges is almost ten times that of community colleges.[98] These increased costs, including for textbooks and lab materials, are especially problematic for many transfer students. As the transition from community to independent college can entail a move from part- to full-time enrollment for most, students experience more costs within a single academic term while also having less time to earn wages to help cover them.[99] Similarly, unless students are able to transfer to a four-year school that is near their previous two-year institution, the residential-leaning makeup of most independent college campuses come with (often mandatory) housing and meal plan costs for students who are used to commuting, which can pose a significant additional challenge.[100] Independent colleges might consider waiving, reducing, or even eliminating high-cost, non-academic elements of their programming in order to ease the financial burden for students coming from community colleges.

Virginia’s Eastern Mennonite University (EMU) is an example of a traditional liberal arts school dedicating time and resources to its transfer students. Students interested in transferring to EMU meet with a transfer admissions counselor who is trained in the school’s financial aid process and can help students make informed decisions before matriculating. EMU has also allocated a relatively generous proportion of its financial aid to transfers, offering transfer-specific scholarships and need-based aid, as well as merit scholarships of up to $16,000 a year for all eligible transfer students. EMU also waives their on-campus housing requirement for certain students, which means that most transfer students are not forced into purchasing expensive housing and meal plans that drastically increase their student fees.[101]

Recommendations and Next Steps

Given the promising strategies for improving community college to independent college transfer pathways detailed in the previous section, this report concludes with specific recommendations for individual independent colleges and independent consortia.

Seek Academic Strategies that Strengthen Two-Year Transfer-In

As discussed in the “Academic Dimension of Transfer” section, we suggest three strategies for realizing the opportunity around community college to independent college transfer—articulation agreements, major-specific pathways, and transfer portals—and argue for why academic practices are especially well-positioned for independent colleges to tackle at the consortia-, region-, and state-levels. There are several ways that independent colleges can begin or continue to leverage these policies.

The first step for independents not currently involved in multi-institutional agreements is to research what neighboring private and public four-year and community colleges are currently doing to facilitate the block transfer of core curriculum. Do these policies ensure junior level status? Have there been particularly successful agreements that groups of institutions in the same region and state are utilizing? How can these agreements be improved upon to better serve community college students so that transfer to independent colleges ensures no lost or excess credit? Forming a taskforce with faculty and administrators across the college to investigate available opportunities—or the lack thereof—will be especially informed if it also includes current students and alumni from the independent college who began their education at two-year institutions. Inviting community college and public university faculty and staff to these discussions will also allow for diverse perspectives on the nuances of transfer within a particular region. By studying the full landscape of transfer practices in the area, independent colleges will be able to design actionable strategies that build off the work already being done.

In the absence of regional multi-institutional transfer practices to join, private colleges might consider convening the members of their independent consortia to begin building a group articulation agreement. This includes forming relationships with state community college leadership and inviting them early to all consortia efforts to this end, ensuring that discussions steer toward the transfer of a package of coursework rather than individual credits, include plans for navigable maps in specific majors that clearly and directly lead students to the bachelor’s degree, and anticipate the ability to automate much of this work through online transfer portals that make the process transparent to potential transfers. (See the resources found in Appendix A for organizing such a gathering, such as “Tackling Transfer: A Guide to Convening Community Colleges and Universities to Improve Transfer Student Outcomes” and “Unlocking the Power of Collaboration.”)

Independent colleges already participating in consortia- or state-level academic transfer policies can still work to further improve their academic transfer strategies. For example, major-specific pathways are relatively uncommon in the private sector, even when strong articulation agreements are in place. Similarly, very few agreements leverage the power of transfer portals. It is worth reaching out to institutions and organizations highlighted in this report to learn from their experiences in implementing these academic strategies. All independent colleges—both those beginning to implement their first academic transfer practices that specifically target community college students and those more seasoned in welcoming these students to their campus—should ensure their policies involve continual recalibration and development, at both the individual institution- and consortia-level. Working to better serve community college students transferring into private schools takes ongoing rather than singular action.

Consider Financial Implications for Community College Transfer

A full analysis of the financial implications of strengthening the transfer pathway between community colleges and independent colleges is beyond the scope of this report. While the financial considerations individual institutions must contend with will be shaped by the specific academic strategies they choose to incorporate as they develop their community college transfer initiatives, the information and strategies presented in this report raise a number of overarching considerations and unresolved questions that are worth highlighting.

An initial consideration for institutions pertains to the one-time and ongoing investments they may need to make, as outlined earlier, in additional recruitment and orientation activities and materials, financial aid packages, advising and financial aid personnel, and tailored on-campus supports.[102] The financial implications of such an investment are complex, as institutions weigh their unique circumstances to strike a delicate balance between attracting enough families that can pay the costs and providing appropriate supports to the right number and type of students with financial and other needs. At the same time, as we discuss in more detail below, there may be hidden fiscal benefits to institutions that need to be taken account. Even if the costs of further developing this pathway may be offset down the road, institutions must weigh their ability to make these upfront investments, as well as the interim institution-wide trade-offs or consequences that will accompany them.

While the anticipated costs are usually top of mind for stakeholders involved in this process, the potential benefits from developing this pathway for many institutions may be understated and worth further exploring. For example, in the context of an effective consortium-wide articulation agreement, community college transfer students would quickly add to upper-level courses and drive down the cost per student to run those classes. With the right supports in place, their shorter time-to-degree could also translate into substantial financial aid savings for some institutions. For example, the Aspen Institute estimated that for a group of private high-performing four-years participating in the American Talent Initiative, the financial aid required to enroll and graduate an average cohort of community college transfer students is around $1.27 million less than that required for an equivalent cohort of traditional first-year students.[103] At the same time, some of these benefits may not materialize if students do not bring in tuition revenue for the institution.

In this regard, tuition-free and debt-free community college policies may allow community college transfer students to apply Pell grants and loans to their tuition at independent colleges, thus generating valuable tuition revenue. Additionally, private institutions committed to improving transfer outcomes can also seek external sources of funding to cover the costs associated with supporting transfers. Grant funding is one consideration when institutions feel they do not have the money to support community college transfer students, particularly at the consortium-level. For example, private institutions are may apply for grants from the federal government to bolster services for their underrepresented students under the Office of Postsecondary Education’s Student Support Services program.[104] The CIC’s State Councils National Venture Fund Grant Program, for example, funded both Texas’ and North Carolina’s transfer portals, and the Teagle Foundation is presently seeking to fund groups of institutions focused on the academic dimension of securing transfer access to and success in the liberal arts.[105]

Finally, the cost of supporting these transfer students does not need to be borne by the four-year institution alone. Some of the work needed to successfully transfer and graduate these students has to happen at the community college level. Community colleges will also need to invest in active advising that includes helping students determine their major or area of interest while still at community college, monitoring student progress to ensure credit completion, and helping students gain access to needed financial resources. Two-year colleges also need to be active in using data and seeking partnerships with four-year institutions that can benefit their students. Another key component for successful transfer is preparing students for the academic, financial, and personal demands of pursuing a bachelor’s degree; students that come into a small independent college armed with the necessary preparation are more likely to successfully complete their bachelor’s degree. Community colleges can ensure that support services exist for potential transfer students and that students receive clear and high-quality information about transferring to various four-year institutions. A consortium approach by independent colleges can incentivize community colleges to that end by creating the scale needed to justify directing resources toward strengthening such pathways (versus supporting multiple relationships with individual four-year institutions that will ultimately result in only few successful transfers). Consortia-led approaches can also be helpful in securing state aid: This has worked successfully for the Independent Colleges of Washington, which secured independent college inclusion of the Washington College Grant, which covers “full tuition at any in-state public college or university, including community or technical colleges” and is portable to “provide a comparable amount toward tuition and other education-related costs at an approved private college.”[106]

Collect Data to Enable Steady Evaluation of Transfer Initiatives

In order to evaluate institutional transfer initiatives, both community colleges and independent colleges must proactively collect data on their transfer activities and their transfer student outcomes. Experts recommend developing “cradle through career” metrics, including the use of transfer alumni surveys.[107] Such mission-aligned methodology would entail both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis and would allow programs to alter and adjust their transfer interventions to improve student success. Example metrics might include recruitment statistics, application completions, financial aid awards, credit transfer figures, persistence rates, and bachelor’s degree completion. Such information would preferably be broken down by student subgroups such as ethnicity and income-level, and available to be compared to that of native students.[108]

While relatively few private universities have focused their attention on transfer data, some public institutions have begun realizing the potential for data to inform and improve transfer outcomes. Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), a public research university serving a large proportion of underrepresented minority students, has developed a plan to use data from both VCU and its community college partners to improve transfer success.[109] VCU will provide qualitative and quantitative data on community college transfers from enrollment to academic performance to student outcomes. Partnering community colleges will also provide data on which of their students are in particular transfer programs and what the outcomes are for those students. The combination of all this information will allow VCU to more effectively coordinate with its community college collaborators to ensure that transfer students are matriculating and graduating. If a certain program were doing well at transferring students, for example, such information would lay a data-driven foundation for establishing a program-specific articulation agreement. Whatever the outcome, the use of data in this strategic way is sure to benefit future community college transfers making the transition to any four-year institution.

Create a Transfer-Centric (not Receptive) Campus Culture

Faculty championship of transfer is critical in order for independent institutions to embrace community college transfer strategies. As one recent report on two- to four-year transfer argues: “faculty are essential stakeholders in supporting transfer success,” yet “efforts to expand access and integrate transfer students into the four-year community can be especially difficult when faculty harbor reservations about course equivalency and student academic preparedness or resist accommodating transfer student needs during critical transition periods.”[110] There are several strategies to overcome this challenge, but the first step is to hold an internal educational campaign to show faculty how transfer students can succeed in their classrooms and dismiss unfair, false bias against community college students such as their inability to handle faculty members’ upper-level curricula.[111]

Both independent and community college faculty should increase their understanding of transfer students attempting to take this specific transfer pathway. This is a two-way street: There is much work be done in bridging trust between these two educational sectors; forming relationships at the faculty-level is a fruitful avenue toward this end.

Perhaps the best way to convince private four-year faculty that community college students can succeed in their classrooms is through direct collaboration with two-year faculty. Both independent and community college faculty should increase their understanding of transfer students attempting to take this specific transfer pathway. This is a two-way street: There is much work be done in bridging trust between these two educational sectors; forming relationships at the faculty-level is a fruitful avenue toward this end. As the CCRC’s “Transfer Playbook” explains, when two- and four-year faculty “work collaboratively with colleagues from partner institutions to create major-specific program maps…institutional partners have nurtured a shared understanding among faculty and staff at each institution about instructional content and expectations and how to guide students successfully through the transfer process.”[112]

A ripe opportunity for this relationship building is in the co-development of major-specific pathways. Explains Council of Independent Colleges Vice President for Development David G. Brailow, “once these groups start working with one another on specific disciplinary pathways, the trust and respect essential to creating a true culture of transfer are strengthened.” This has been done with great success in Michigan during the formation of the state’s MiTransfer Pathways initiative. Eight hundred Michigan faculty members across community colleges, public universities, and independent colleges met during full day convenings in order to identify which courses should apply to the bachelor’s degree in 12 fields. This in-person engagement allows for practice sharing and conversation centering on transfer student experiences, and ultimately, the cross-sector faculty engagement has served an unmet need in Michigan to better serve these learners.[113]

Of course, faculty buy-in alone will not lead to a transfer-centric culture, and relationships at the administrative level between community and independent colleges also need development. In order to implement academic, cultural, and financial strategies for strengthening community college transfer students’ access and success in independent four-year colleges, individual institutions will need to embrace a transfer-centric culture. This change in strategy will potentially be met with pushback, as is the case for many structural changes within institutions. However, clear direction from college leadership across various institutional departments can alleviate this. Truly embracing a transfer-centric campus culture requires buy-in from faculty, offices of academic affairs, deans, offices of student life, registrars, offices of financial aid, among other key stakeholders at the college.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following people for their contribution to this work:

- David G. Brailow, Vice President for Development, Council of Independent Colleges

- Erica Lee Orians, Executive Director Michigan Center for Student Success, Michigan Community College Association

- A. Hope Williams, President, North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities

Appendix A: Resources

Awarding Transfer Credit

Brooks, Kelly et al. “A Guide to Best Practices: Awarding Transfer and Prior Learning Credit.” American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers, 2017, https://www.aacrao.org/docs/default-source/signature-initiative-docs/trending-topic-docs/transfer/guide-to-best-practices.pdf.

This document describes expectations and best practices for post-secondary institutions’ work with transfer credits. These guidelines are intended to assist and advise—not prescribe—member colleges and universities in this work.

Hodara, Michelle et al. “Improving Credit Mobility for Community College Transfer Students.” Education Northwest, 2016, http://educationnorthwest.org/sites/default/files/resources/improving-credit-mobility-508.pdf.

This study investigates the issue of credit mobility in 10 states: California, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington. It provides a unique opportunity to understand multiple policy approaches to credit mobility and how these policies play out and, potentially, break down at the campus level. The study utilizes qualitative data from policy documents and legislative statutes, phone interviews across the 10 states, and interview data collected during site visits to two- and four-year colleges in Texas, Washington, and Tennessee.

Example Articulation Agreements

“Independent Comprehensive Articulation Agreement Between the North Carolina Community College System and Signatory Institutions of North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities.” North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities, 2015, https://ncicu.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/ICAA_30-campuses_updated-10.22.19.pdf.

This articulation agreement details the partnership between the North Carolina Community College System and North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities. This pioneering agreement is one of the first of its kind and can provide an example for consortia of independent institutions seeking to establish a similar agreement.

“Articulation Agreement Between the Independent Colleges and Universities of Florida and the Division of Florida Colleges,” Florida Department of Education, 2013, http://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/5421/urlt/0078475-icuf_agreement.pdf.

Another example of an articulation agreement signed between a group of community colleges and independent institutions comes from Florida. This articulation agreement served as a spur for several other articulation agreements signed between Florida’s community colleges and other independent colleges and universities.

Creating a Transfer-Friendly Culture

Herrera, Alfred and Dimpal Jain. “Building a Transfer‐Receptive Culture at Four‐Year Institutions.” New Directions for Higher Education 162 (2013): 51-59, https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20056.

This chapter reviews a four-year university’s role in developing and implementing a transfer-receptive culture. In particular, it focuses on key practices such as establishing transfer for non-traditional students as a high institutional priority.

Hannon, Charles. “Facilitating Transfer Students’ Transition to a Liberal Arts College.” College and University 89.1 (2013): 51–56.

This article discusses the efforts undertaken by Washington and Jefferson College to accommodate the needs of transfer students. The article discusses evaluating student transcripts, creating a space for transfers on campus, and ways the college can continue to improve in its efforts to better serve transfer students.

Improving Transfer Student Outcomes

Deane, KC et al. “Tackling Transfer: A Guide to Convening Community Colleges and Universities to Improve Transfer Student Outcomes.” Community College Research Center, 2017, https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/tackling-transfer-guide-convening-community-colleges-universities-improve-transfer-student-outcomes.html.

In an effort to improve transfer student success, the Aspen Institute, CCRC, Public Agenda, and SOVA have released this implementation guide designed to help state or consortial entities organize workshops within which teams from two- and four-year institutions work together to improve transfer and graduation outcomes for their students. Through data analysis and self-reflection of institutional practices, these workshops help institutions develop action plans (individually and among partners) to improve transfer student success.

Wyner, Joshua et al. “The Transfer Playbook: Essential Practices for Two- and Four-Year Colleges.” Community College Research Center, 2016, https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/transfer-playbook-essential-practices.html.

This playbook is a practical guide to designing and implementing a key set of practices that will help community colleges and their four-year college partners improve transfer outcomes. The playbook is based on the practices of six sets of community colleges and universities that together serve transfer students well. These institutions have higher than expected rates of bachelor’s degree attainment for degree-seeking students who start at community college and transfer to a four-year institution—after accounting for their student demographics and institutional characteristics.

“Strengthening the Transfer Pathway: From Community to Four-Year Private Colleges.” Edvance Foundation, 2015, http://edvancefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/EDVANCE-TransferReport-FINAL.pdf.

The Edvance Foundation (now Academic Innovators) set out to develop a program that would increase the flow of community college graduates to four-year private colleges and universities and enhance students’ prospects for success. As part of its program planning, the Edvance Foundation surveyed the literature, examined prevailing and best practices, and initiated an 18-state listening tour, panel discussions, and webinar series with higher education leadership. In addition, the Edvance Foundation partnered with Human Capital Research Corporation to administer the largest survey ever undertaken on transfer practices at private, four-year undergraduate institutions. In all, 414 schools completed the survey, representing 25 percent of those sampled. The findings are presented in this report.

Jenkins, Davis and John Fink. “Tracking Transfer: New Measures of Institutional and State Effectiveness in Helping Community College Students Attain Bachelor’s Degrees.” Community College Research Center, 2016, https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/tracking-transfer-institutional-state-effectiveness.pdf.

This report is designed to help improve transfer student outcomes by helping institutional leaders and policymakers better understand current outcomes and providing them with metrics for benchmarking their performance.

Enrolling Transfer Students

Jacobs, Bonita C. “The College Transfer Student in America: The Forgotten Student.” American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers, 2004, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED489802.

This guide translates research into practical advice on attracting, retaining, and guiding transfer students. Various chapters address multiple strategies for orientation and advising; curricular issues involving transfer students; how to maximize the effectiveness of articulation agreements; preparing community college students for transfer; non-traditional students as transfers; and how to develop support from alumni who started as transfer students.

“Improving Student Transfer from Community Colleges to Four-Year Institutions—The Perspective of Leaders from Baccalaureate-Granting Institutions.” The College Board, 2011, https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/public/pdf/rd/11b3193transpartweb110712.pdf .

This report highlights the perspective of four-year institution leaders who have had success in recruiting, enrolling, and serving transfer students. It is hoped that their insights will assist other four-year college and university leaders who wish to enroll and educate transfer students from community colleges.

LaViolet, Tania et al. “The Talent Blind Spot: The Practical Guide to Increasing Community College Transfer to High Graduation Rate Institutions.” American Talent Initiative, 2018, https://americantalentinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Aspen-ATI_Vol.2_The-Practical-Guide_07112018.pdf.

“The Talent Blind Spot” demonstrates that, each year, more than 50,000 high-achieving, low- and moderate-income community college students do not transfer to a four-year institution. Approximately 15,000 of these students have a 3.7 GPA or higher, which suggests they could succeed at even the most competitive schools. The report also demonstrates that high-graduation-rate colleges and universities enroll far fewer transfer students than other four-year institutions. The report offers a path forward based on the work of several ATI member institutions that have demonstrated that creating robust community college transfer success is possible through strong, leadership-drive partnerships, early outreach and advising, and dedicated, holistic supports.

Consortial Thinking