What Do Our Users Need?

An Evidence-Based Approach for Designing New Services

Introduction

In the face of evolving user needs, many academic libraries are reimagining the services they offer. As instruction moves online, how can libraries best provide support for teaching and learning? As research becomes more reliant on data, computation, and collaboration, where can libraries best add value? As colleges welcome more diverse student populations and greater contingent faculty labor to campus, what is the library’s role? As budgets shrink, how should a library prioritize which resources and services to provide?[1]

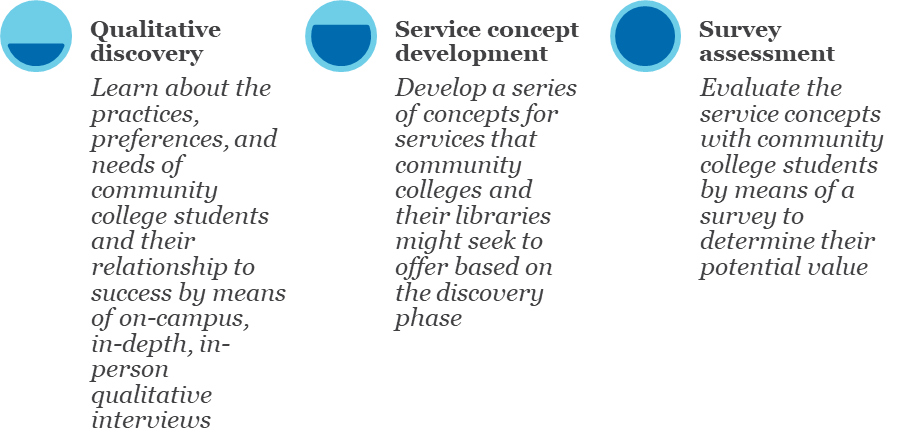

For many years, Ithaka S+R has provided strategic intelligence to libraries about the changing needs of their faculty and students.[2] More recently, within the context of an IMLS-funded project focused on students across seven community colleges, the Community College Libraries & Academic Support for Student Success (CCLASSS) project,[3] we have developed a methodology for designing and evaluating new library services: service concept testing.[4] Service concept testing is a mixed-methods market research process, guided by a participatory decision making framework, and entails gathering data on user needs, generating possible offerings, and testing those offerings.

At its core, service concept testing is driven by evidence and bolstered by creativity. We start with discovery by identifying the expressed needs of a target community. Discovery is followed by service concept development where libraries brainstorm specific service ideas that address the needs uncovered. Finally, these concepts are assessed by surveying the target community to gauge their potential value.

This methodology was initially piloted with multiple college partners over the course of two years, and we believe that a similar process could be implemented on a much smaller scale within a single institution, across a group of four-year institutions and/or mixed institution types, or beyond the library with additional types of service providers in the higher education sector. This issue brief serves as an introduction to our methodological approach, walks through the phases of work in the CCLASSS project to illustrate in practice the steps involved, and suggests how others can adapt this process for their own context.

Discovery

We begin by gathering evidence about the needs of the user community we wish to serve more effectively.

Initial evidence gathering can take a few forms and should include both an examination of existing data and, if necessary, the gathering of new insights. Existing data sources might include direct measures of user behavior or self-reported perspectives, and these data may be located within the library, the parent institution, or broader sources. Existing data should inform new data gathering processes but also leave room for further open-ended exploration without making unfounded assumptions about the unmet needs of the user community under study.

For the CCLASSS project, we conducted interviews with dozens of students across seven community colleges, including primarily face-to-face interviews for students taking in-person courses but also interviews via telephone to accommodate those with complicated schedules or taking principally distance/online learning courses.[5] In this case, the interviews were intended to supplement what was already known from existing research on this user community, informed by an extensive literature review, as well as local expertise at the college level from project leads at each of the partner colleges. Together this evidence informs the development of service concepts.

Service Concept Development

In developing the service concepts, we draw richly on the evidence base and employ a collaborative, inclusive, iterative, facilitated process with librarians from the institutions in question.

Once the evidence has been gathered and analyzed, it’s time to bring together the project group. Depending on the scope of service provision, the project group might consist of multiple individuals from a single department within an institution, across departments within an institution, or across multiple institutions. Before and throughout the service concept development process, the project group should be immersed in the data gathered in the initial discovery phase to center discussion on user practices, preferences, and unmet needs. Ideally, someone outside the library can serve as a facilitator to keep the team focused on service concept development.

For the CCLASSS project, this development process was centered around an in-person, full-day workshop with project leads at seven partner colleges as well as with three project advisors. Prior to the workshop, findings from the initial discovery phase, which centered around in-depth user interviews, were summarized and circulated.

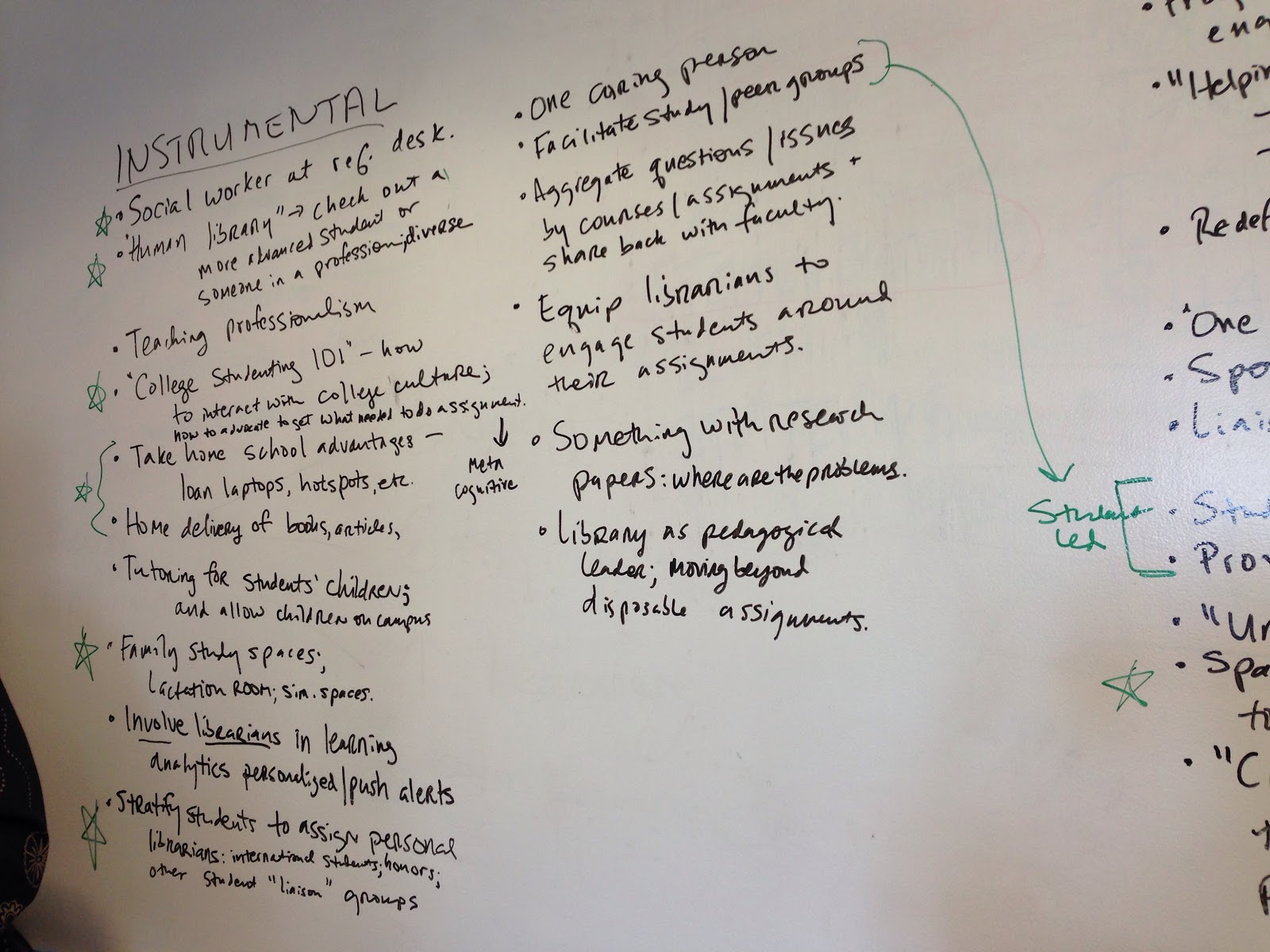

The preparations for this workshop, and the workshop itself, were facilitated by Ithaka S+R as a third party to the libraries which sought to develop the right array of service concepts to best serve their students. Ithaka S+R staff served as discussion facilitators, with the project co-PI and advisors also prompting discussion. All ideas were instantly recorded on a whiteboard, allowing us to visualize our progress and make transparent our thinking and decisions during the course of the day.

Principle 1: Brainstorm first; narrow and prioritize later

We encourage open brainstorming first, waiting until later in the process to focus in on specific service concepts.

Before the brainstorming begins, the participants should spend focused time immersed in the initial findings on user needs and generating individually a number of possible service offerings. Prior to our workshop, we circulated research findings along with a pre-meeting activity worksheet to attendees to encourage development of ideas for possible service offerings in advance of the meeting and to set expectations for the meeting itself. We intentionally left the instructions quite broad so as to gather a diverse range of ideas. Prioritizing and narrowing ideas should happen much later in the process, and we didn’t want attendees to feel inhibited or restricted during this idea generation phase. Then, in person, we reviewed each participant’s ideas for new services and brainstormed together from that starting point about additional possibilities and prospects.

The primary purpose of the design workshop is to develop an extensive list of possible service concepts that can be iterated on and fully prioritized at a later time. Making sure all participants understand the scope of the workshop is essential so that they focus on idea generation rather than judging or selecting specific concepts. There is ample time later in the process for honing in on a final list of service concepts to test.

Principle 2: Center design on user community goals, challenges, and needs

The service design process may become decoupled from evidence about the user community, and while some flexibility is always warranted, it is essential to continuously return to the research during the brainstorming process.

What findings from the discovery phase should drive service concept development? A grounded theory approach can provide insights from the qualitative discovery phase to move the conversation beyond what users reported toward deeper insights on unmet needs and possible solutions. In the case of the CCLASSS project, we identified four main thematic areas of findings from our qualitative work and used these to draft a series of focused questions to prompt discussion.

Throughout the workshop, always centered our idea generation on student goals, challenges, and needs. Given the student-centric scope of our project and the rich qualitative dataset we had gathered going into the design process, it would have been irresponsible to put the library, its employees, or the colleges more broadly in a relatively more privileged position. Given this principle, we emphasized both in the pre-meeting activity instructions and throughout the design process that what students shared with us would largely guide our thinking. At times, when the conversation focused too narrowly on current roles and resource constraints of the partner libraries, facilitators circled back to the qualitative findings to re-center subsequent discussion around student needs.

Principle 3: Consider the unique contributions of the library

User community needs must be artfully combined with the expertise, resources, and other comparative advantages of the library in order to develop services.

While we center our design on student needs, we also deeply consider the unique current and possible future contributions of the library in translating needs to services. During the 2019-20 academic year, each of the CCLASSS project partner libraries will be responsible for implementing one or more of the service concepts at their institution, so the ideas needed to be grounded in what the library might actually be able to provide. Throughout the day, we aimed to move discussion beyond the current role of the library while also respecting some of the very material challenges they might face in service implementation.[6]

Conversation around the qualitative findings was rich, leading to a long list of ideas for how community colleges and their libraries could better meet student needs. Ithaka S+R staff along with our co-PI and project advisors facilitated the workshop discussion by probing further on ideas offered to generate a shared understanding of possible directions, providing space and structure for all attendees to contribute, and negotiating across attendees when disagreements arose.

Ideas recorded on a whiteboard during the workshop

Principle 4: Prioritize collaboratively

It is often difficult to prioritize potential service concepts by committee or consensus—and impossible to achieve unanimity. The organizer or facilitator should lead this work, taking a collaborative and inclusive approach.

At the end of the CCLASSS design workshop, we arrived at a list of approximately 50-60 ideas for services, some of which were very well developed and some of which were not. We spent the final portion of our time together reviewing the list and prioritizing (in this case, by starring) those ideas that seemed to hold the most promise for helping address students’ unmet needs. We left the meeting with a dozen or so of these most promising ideas tagged for further development.

After the workshop, we spent several weeks further iteratively developing the service concepts we would test. This involved drafting the concepts, circulating them among project team members, revising and recombining several of them, a voting/scoring process, and making recommendations along the way to help guide toward final decision making. After these service concepts and exploratory follow-up questions were drafted, we circulated them to the project leads and advisors. We gathered feedback via email and conference calls over a matter of weeks, incorporated the feedback into the concepts, and then went through another round. The goal here was to ultimately test a robust portfolio of concepts for testing, aligned with the breadth and scope of what was gleaned from earlier user insights and subsequent facilitated discussion, rather than to build consensus on actual offerings. Without a strong facilitator for this work this prioritization process could have dragged on for many months.

Principle 5: If working across institutions or departments, recognize local differences

Planning for service concept development is in many ways an institution—or department-specific—undertaking, so planning collaboratively for the prospect of collaborative service offerings requires especially sensitive facilitation.

The CCLASSS project envisioned a set of collaboratively developed, and possibly consortially administered, service offerings. With this in mind, we intentionally brought together as part of the participating library cohort four college libraries from a single university system to examine the prospect of collaborative service development.

Having identified possible services to test, we generated short descriptions for each. While there were some similarities across the institutions involved in this project, there were also notable differences in existing services and resources available for new service development. Therefore, we crafted the service concept descriptions with enough specificity that students could react to something concrete, but left them general enough so that they could be adapted and adopted by institutions in different ways (see the Appendix for full list).

Principle 6: Advance several concepts rather than seeking unanimity

The objective of service concept development is not to develop actual services but rather to allow for the testing of strong hypotheses about what services might be valued.

For this project, it was not possible to achieve perfect agreement across all involved parties on what service concepts were most important to test. For some partners, the set of proposed concepts included all of those that they wished to see included; for some, the set excluded some set that they wished to see included; and for some, the set included some set that they did not wish to see included. However, the benefits associated with administering a single evaluation instrument—in this case, a survey—outweighed those that might result from a more customized approach. The group was ultimately able to come to some agreement on a set of eight concepts to test across the seven institutions.

Service Concept Testing

While service concepts have by design been grounded in the unmet needs of a user community, testing them with potential service users reveals actual demand.

Once the service concepts have been developed, how are they incorporated into an appropriate tool for evaluation? For the CCLASSS project, given the interest in not just examining aggregate results across the seven partner colleges but also stratified results by college and a variety of student demographics, we opted to field a large-scale survey with invitations to roughly 15,000 students at each college. As with any Ithaka S+R survey, we tested the service concepts in the context of the overall instrument to ensure they were understood clearly and consistently across the community of potential respondents prior to launching the survey. We incorporated feedback from student testers and prepared to field the survey.

Each respondent received a randomly selected subset of the eight service concepts (see the Appendix for full list) within their questionnaire to reduce survey duration. If the respondent indicated that a service concept was valuable, they were presented with a series of related follow up questions. If the respondent indicated that the service concept was not valuable at all, these additional questions were skipped and the next, randomly ordered service concept was displayed. After analyzing the survey results, Ithaka S+R shared and published the findings.[7]

Service Piloting

Once a service concept is assessed to be promising, the next step is to pilot an actual service offering.

The findings from the service concept development process enabled each library to see which services resonated most richly with its user community and make an evidence-informed decision about which service or services to pilot. As part of the CCLASSS project, each participating library was responsible for piloting at least one of the services developed. That said, the grant required only that each institution would pilot a service, and not necessarily offer it permanently or at scale.

Because the service concepts were not in and of themselves concrete or literal service offerings, they were then developed into prototypes by the college leads for local implementation. Each of the project leads was responsible for considering their institution-specific findings alongside other local data points and translating the selected prototype(s) into action. The testing of multiple service concepts enabled analysis of results on each concept individually and in context against one another. Recognizing that self-reported accounts of future behavior and future behavior itself does not provide a 1:1 ratio, triangulating the survey results with other data and considering each concept in context against other concepts was essential for interpretation and decision making.

During the course of a pilot, there should be some form of assessment designed to determine whether to bring the service into “production operation,” to end it, or to extend the pilot in order to gather more evidence. We look forward to sharing more about the service prototyping via piloting in early 2020.

Final Thoughts

Successful implementation of service concept testing requires valuation of user perspectives, creativity and openness to new approaches, comfort with brainstorming before prioritization, and a strong facilitator to bring groups of individuals through the process together.

This approach may be implemented at larger and smaller scales, across and within institutions. Library consortia might consider utilizing this approach for developing shared offerings across institutions, while librarians and student affairs professionals could similarly partner to develop a holistic user experience within a single institution.

Further, while this issue brief has focused on developing services for students, the service concept testing methodology can be implemented with any campus community. In fact, it can even be implemented with subgroups of a given campus community—for example, researchers in STEM fields or first-generation students.

Higher education institutions often need to gather additional evidence beyond what is currently available to inform the development of new service offerings. Service concept testing is one methodology that can enable this process.

Appendix

Service concepts and their descriptions as displayed to respondents; in order from highest to lowest rated value.

| Service Concept Short Name | Full Description |

|---|---|

| Knowledge Base | Imagine that the college offered a single point of contact for whenever you need help navigating any part of college including advising, registering for classes, applying for financial aid, securing personal counseling, and obtaining tutoring or other coursework assistance. This service would offer expertise in connecting you with the right college employee for assistance. |

| Loaning Tech | Imagine that there was a place at your college where you could access technology either to borrow for use outside class and at home, or use on-site with expert training and assistance. The equipment available might include options such as a ‘one-touch studio’ for recording video presentations, 3-D printers, large-format poster-size printers, virtual reality headsets, multimedia editing computers and software, digital audio/video recorders, laptops, tables, chromebooks, scientific calculators, Wi-Fi hotspots, and black/white or color printers for on-site use and/or checkout. |

| Personal Librarian | Imagine that a dedicated professional employed by the college would be available to help you find and use all kinds of content sources you might need for your coursework, including books and journals, in paper, and on the internet. This professional would provide help in person or via email, phone, or chat on any assignment. |

| Social Worker | Imagine that a social worker was readily available at your college to help you any time you needed personal assistance. Depending on your needs, they could assist you with finding housing, securing childcare, finding reliable transportation, seeking public assistance, and/or navigating other life challenges. The social worker would offer drop-in hours, and they would also be “on call” if you had a personal emergency during non-working hours. |

| Child Care | Imagine that there were an array of services at the college to accommodate students who have children of their own or are caregivers while you are attending class. These services might include designated spaces for families to study together, both regular and emergency childcare programs, and tutoring and other afterschool services for children. |

| Privacy | Imagine that there was a workshop you could take about how to operate effectively and safely in today’s digital world. This would include a practical guide on how to choose which digital services to use, how to encrypt sensitive communications, and how to delete your activity trail and presence. Each student would be guided in finding the right balance between using personalized services and the privacy interests that these services may minimize. |

| Community Advocacy | Imagine the college made available opportunities that would help you better develop your capacity as a member of your community and society. These could include one-time presentations by faculty, members of community groups, industry experts, or fellow students, and can take the form of workshops, ongoing discussion groups, informal meetups, or online resources. Rather than seek to educate you on particular political perspectives, the goal would be to help you develop your own perspective and strategies for engagement, so you could participate on issues that are important to you as a citizen, an informed member of society, an activist, or whatever other role you choose to assume. |

| Student Showcase | Imagine that the college offered you and fellow students an opportunity to publicly display work from your classes, or to contribute personal and professional expertise developed outside of classes, through various displays, presentations, workshops, and more, either in person or virtually. You would have a space in which you could gather with other students to share your experience, expertise, and work, as well as learn from other students. |

Endnotes

- We thank Bryan Alexander, Braddlee, Lettie Conrad, Alex Humphreys, Kimberly Lutz, Claire Stewart, and Frankie Wilson for providing comments and suggestions on a draft of this issue brief. ↑

- Ithaka S+R has conducted single site, cross-institutional, and national research on faculty and student needs through our triennial national faculty survey (see Melissa Blankstein and Christine Wolff-Eisenberg,” Ithaka S+R US Faculty Survey,” Ithaka S+R, 12 April 2019, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.311199), research and teaching support services program (see Danielle Cooper, “Joining Together to Support Undergraduate Instruction,” Ithaka S+R, 3 April 2018, https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/joining-together-to-support-undergraduate-instruction/), and local surveys program (see https://sr.ithaka.org/our-work/surveys/). ↑

- Through the Community College Libraries & Academic Support for Student Success (CCLASSS) project, we have now (1) examined student goals, challenges, and needs from the student perspective, (2) developed a series of services that target these expressed goals, challenges, and needs, and (3) tested the demand for these service concepts. This project, co-led by Northern Virginia Community College and Ithaka S+R, along with six other community college partners and support from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) [RE-96-17-0113-17], focuses on strengthening the position of the community college library in serving student needs. Over the past two years, we have issued reports on our initial qualitative findings on student practices, goals, and challenges, as well as their responses to the service concepts tested via survey. For more on our findings, see Christine Wolff-Eisenberg and Braddlee, “Amplifying Student Voices: The Community College Libraries and Academic Support for Student Success Project,” Ithaka S+R, 13 August 2018, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.308086, and Melissa Blankstein, Christine Wolff-Eisenberg, and Braddlee, “Student Needs Are Academic Needs,” Ithaka S+R, 30 September 2019, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.311913. ↑

- Product concept testing is an established methodology within market research. See for example this Qualtrics guide: https://www.qualtrics.com/experience-management/product/how-concept-test/. We are not aware of any previous effort to adapt product concept testing for utilization in service concept testing for an academic institution or academic library as we have done in this project. ↑

- Christine Wolff-Eisenberg and Braddlee, “Amplifying Student Voices: The Community College Libraries and Academic Support for Student Success Project,” Ithaka S+R, 13 August 2018, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.308086. ↑

- It is important to note that when testing the services with students, we presented the survey in a neutral fashion so as not to influence responses towards the library in a favorable manner. ↑

- Melissa Blankstein, Christine Wolff-Eisenberg, and Braddlee, “Student Needs Are Academic Needs,” Ithaka S+R, 30 September 2019, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.311913. ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.