Academic Library Strategy and Budgeting During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Results from the Ithaka S+R US Library Survey 2020

Executive Summary

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Ithaka S+R surveyed library directors nationally to examine the strategic changes libraries have made to continue operating. A total of 638 library directors responded to questions about library leadership and decision making, COVID-19 management, budget allocations and cuts, collections acquisitions, and personnel changes. The questionnaire also focused on racial justice in light of recent protests including the Black Lives Matter movement and the related increased focus on equity, diversity, and inclusion in higher education. This report focuses on findings related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and an upcoming report will look at the equity, diversity, and inclusion results.

Key Findings

- The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced and accelerated trends in library investments toward digital resources and services. Even before the pandemic, libraries were investing more significantly in purchasing and licensing digital collections over time, and the vast majority of library directors anticipate this trend, along with additional investments in virtual services, to continue in the long term. In five years, directors expect their budget allocations toward online journals and databases, e-books, and streaming media to increase, while investments in print resources decrease.

- Library leaders feel they have been recognized for being well-positioned and prepared for the emergency pivot to support remote research, teaching and learning. About 70 percent of directors felt their library was well-prepared to pivot to virtual services and believed that other senior leaders also recognized this advantage. This may have contributed to directors perceiving their role as more valued than they did previously, reversing the negative trend of decreasing value across our earlier surveys.

- Library directors prioritized staff well-being and organizational finances in their decision-making. Most were able to close and reopen the physical library and allocate changes to collections, operations, and personnel funds fairly independently while consulting other leaders inside and outside of the library. In making these decisions, directors sought to ensure employee safety and well-being at the library. However, in almost one-third of institutions, personnel allocation decisions were made for them by another group in the broader institution. Only slightly more than half had confidence in their institution’s broader safety measures.

- Most libraries have experienced budget cuts in the current academic year and there is great uncertainty about longer-term financial recovery. Seventy-five percent of directors have operated with reduced budgets, with most decreases thus far falling between one and nine percent for the 2020-2021 fiscal year. For the 20 percent of libraries where the year’s budget had not been determined by the time of the survey, there are indications that directors have been subject to expenditure controls, needing to pause spending wherever possible. The majority of library directors remain uncertain about whether the library budget will recover after the pandemic.

- Personnel cuts have most affected those who work in physical library spaces, though library directors view these spaces as crucial to their long-term mission. Employees in access services, facilities, operations, and security were among those most impacted by furloughs, hour reductions, and layoffs. Despite predominately focusing on providing virtual services and resources during the pandemic, and in turn reducing the staff dedicated to in-person service provision, over eight in ten library directors still see their physical locations as essential for carrying out their missions in the long-term.

- Not all types of libraries were affected equally by budget cuts—doctoral universities and public institutions tended to be most impacted. Private baccalaureate college libraries were least likely to experience budget cuts compared to their public counterparts, master’s institutions, and doctoral universities; in fact, roughly half of respondents at private baccalaureate colleges reported not yet having to make any reductions. Public institutions, on average, disproportionately experienced the highest levels of cuts, and doctoral universities were most likely to experience any level of budget reduction.

Introduction

In March of this year, in response to the initial spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, higher education institutions across the country quickly pivoted to online instruction while their libraries closed physical buildings, limited or eliminated access to print collections, and expanded digital offerings. As of the fall semester, many libraries reopened their doors, while many services were still being delivered virtually and some staff continued to work remotely. Safety measures have been widely adopted and access to collections is largely digital or staff-mediated. And now, as new cases of the virus are increasing nationwide, a few viable vaccines are being tested, and a new administration prepares to lead the United States, institutions are planning for another semester that will be greatly impacted by disruptions.

Several months prior to the initial outbreak of COVID-19, the Ithaka S+R US Library Survey 2019 captured strategic priorities and directions of library deans and directors nationally, as we have done on a triennial basis for the last decade. Findings from the regular triennial 2019 survey provide a view of the immediate period before the pandemic struck.

In light of the need for broad evidence about the impact of the pandemic, we fielded a special edition of the survey outside our triennial cycle. The 2020 survey provided library leaders with an opportunity to speak collectively on the impacts of COVID-19 and movements for racial equality on their organizations. This report will focus on the impacts of the pandemic on strategy and finances, while a parallel report on issues of justice, equity, diversity, inclusion, and anti-racism will be published in early 2021.

In many ways, results from this year’s survey, which represent the perspectives of 638 library directors across the country, show us that libraries were relatively well-positioned for this “new normal.” Longitudinal data from prior survey cycles already pointed toward greater provision of digital services and acquisition of digital resources, and the findings of the 2020 survey reinforce this trend.

Despite these preparations, academic libraries, like their parent institutions, are suffering from the serious financial impacts of the pandemic. Many library leaders report significant cuts across operations, collections, and staffing budget lines, while the also work to protect the well-being of their employees and establish the library as an essential campus partner. There is great uncertainty about the likelihood that budgets will recover over the next several years.

As traditional forms of instruction continue to be disrupted and with their budgets facing ongoing headwinds, library leaders will need to continue making difficult decisions that will impact the role and value of the library going forward. For many, this will be a time to critically evaluate, and continuously re-evaluate, which strategies are worth doubling down on, suspending, or perhaps abandoning altogether.

Methodology

Of the 1,473 library deans and directors at four-year colleges and universities across the United States who received emails inviting them to participate in our survey in September 2020, we received completed responses from 638 for an overall response rate of 43 percent. Of these, 83 percent self-identified as white and 64 percent self-identified as women. As in previous survey cycles, response rates differed by Carnegie Classification with 35 percent responding from Baccalaureate colleges, 42 percent participating from Master’s institutions, and 53 percent from Doctoral universities. Previous cycles of the survey, as well as advisor and tester input, led to the creation of the 2020 questionnaire with thematic focus in particular on the impacts of COVID-19 and movements for racial justice.

The data gathered were analyzed using a variety of techniques including frequencies and other descriptive analyses, independent samples t-tests, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD tests, and chi-square analyses. Results of these analyses are reported throughout this report if they are statistically significant at the p <.05 level. We have also noted the frequencies of responses over time, paying particular attention to large differences. See Appendix A for more details on methodology and Appendix B for a detailed breakdown of respondent demographics.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank our Library Survey 2020 advisory board for their input at key stages in this project, especially for their help in establishing the questionnaire. Our advisory board includes:

- K. Matthew Dames, University Librarian, Boston University

- Trevor Dawes, Vice Provost for Libraries and Museums and May Morris University Librarian, University of Delaware

- Amy Kautzman, Dean and Director, University Library, Sacramento State University

- Jonathan Miller, Director of Libraries, Williams College

- Kellie O’Rourke, Head of Library Sales, Americas, Cambridge University Press

- Sarah Pickle, Interim Assistant Dean for Planning and Operations and Director of Organizational Planning and Assessment, The Claremont Colleges Libraries

- Deborah Prosser, Director of Olin Library, Rollins College

- Rachel Rubin, Associate University Librarian for Research and Learning, University of Pittsburgh

- Denise Stephens, Vice Provost and University Librarian, Washington University in St. Louis

We are also grateful to our colleagues who contributed to this project in a variety of ways, including Kimberly Lutz and Roger Schonfeld. In particular, this work would not be possible without the significant contributions of our colleague Nicole Betancourt who administered the survey.

Leadership and COVID-19 Management Strategies

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, strong leadership has been crucial for overcoming challenges and ensuring the continued success of academic libraries, their employees, and their parent institutions. In this survey, we have explored how library leadership strategies and priorities changed as a result of the pandemic. Findings examine the skills library leaders employed to address challenges, their strategies for making decisions, and changes in their relationships with other senior leaders.

Leadership and Institutional Alignment

In fall 2019, just months before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, we asked library directors for the first time to share what knowledge, skills, abilities, and competencies have been most valuable to them in their current position. Comparisons between responses across the two survey cycles demonstrate which of these strengths have been most useful in navigating the many disruptions and events of 2020.

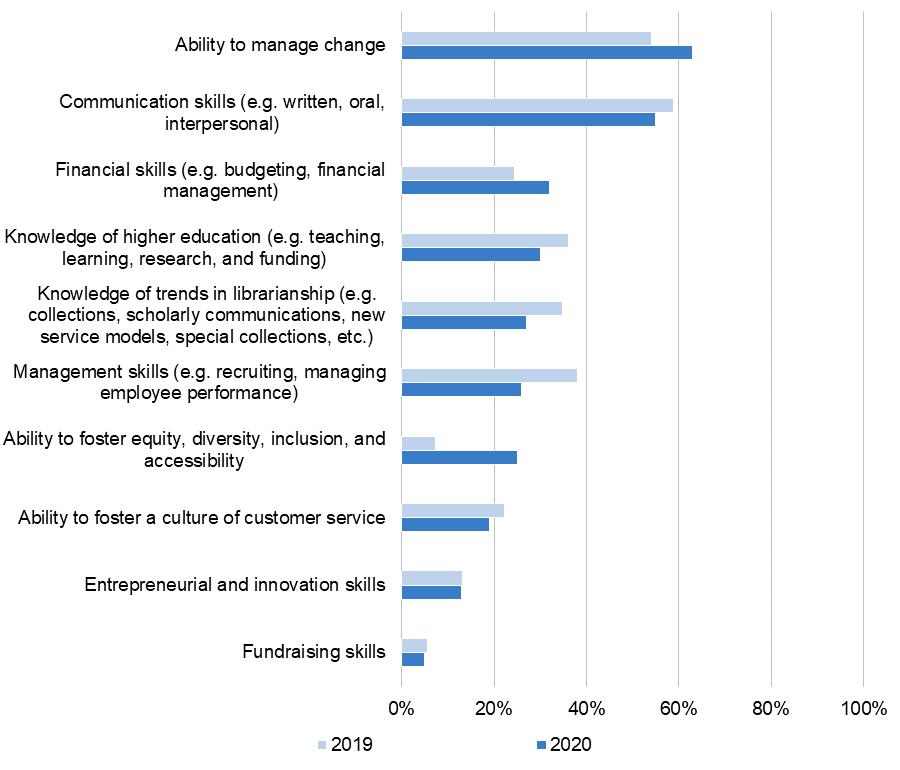

Skills in managing change and communicating effectively were found to be of the utmost importance, with a notable increase in the importance of managing change. As libraries have had to close and operate entirely remotely, many for the first time, there have been numerous changes, both to internal operations and to the provision of services for users, that have had to be made within a short period of time.[1] Managing and communicating those changes has been vital for libraries during the pandemic. See Figure 1.

The value of financial skills and the ability to foster equity, diversity, inclusion, and access also substantially increased over the last year. As student enrollment and state funding have decreased for many higher education institutions, the need to utilize budgeting and financial management skills has naturally increased. Further, as many higher education institutions have declared a renewed commitment to racial justice, the ability to foster equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility is crucial.[2]

Fewer library directors, as compared to the previous survey cycle, viewed management skills, knowledge related to the higher education sector, and knowledge of trends in librarianship as important. As we will discuss later in this report, many library leaders have had to institute hiring freezes, salary freezes, and other across-the-board personnel decisions, which likely contributed to fewer directors selecting management skills, which we defined as including recruiting and managing employee performance, this survey cycle. Further, trends in higher education and librarianship may be less important because directors have had to focus more on issues that are specific to leading their own library in the context of their particular institution.

Figure 1. Which of the following knowledge, skills, abilities, and competencies are currently most valuable for you in your position? Please select up to three items or leave the question blank if none of these items apply.

Percentage of respondents that selected each item, by survey cycle.

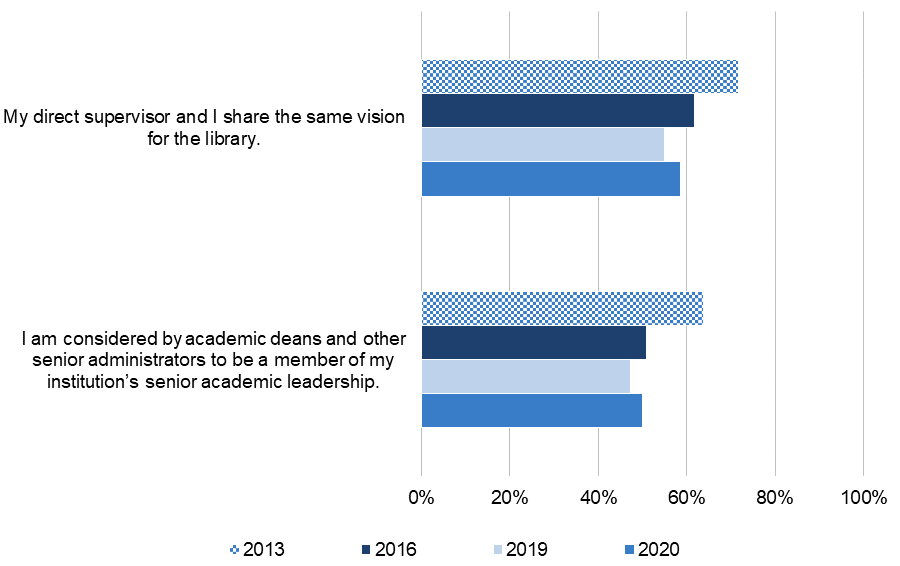

Since 2013 we have asked library directors about their relationships with other senior leaders at their institution, in particular about whether they share a vision with their direct supervisor and whether they feel included in their institution’s senior leadership. While the majority generally agree with these items, historically, their responses have trended less positive over time indicating a perception that they, and by extension the library, have been less valued.[3] This survey cycle, however, directors reported being modestly more aligned and included with other leaders compared to the previous cycle with responses near or approaching the levels we found in our 2016 survey.

One potential reason for this shift is that libraries have been relatively prepared to operate remotely during the pandemic given existing digital resources and services. Indeed, 70 percent of library directors both agreed that their library’s previous digital presence was robust enough prior to the COVID-19 pandemic that they did not need to make many changes to strengthen it and that other senior leaders at their institution recognized this relative strength. Time will tell if this is the beginning of a definitive reversal of the previous negative trend on library and library director value or whether it is merely temporary. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Please use the 10 to 1 scales to indicate how well each statement below describes your point of view.

Percentage of respondents that strongly agree with each statement, by survey cycle.

COVID-19 Response and Decision-Making

We included several new questions in the survey addressing how library leaders made and managed decisions about the library’s operations and budget during the pandemic. In particular, we explored how involved and independent library directors have been in making a variety of decisions, the goals they have aimed to achieve, and what data they collected or consulted in the decision-making process.

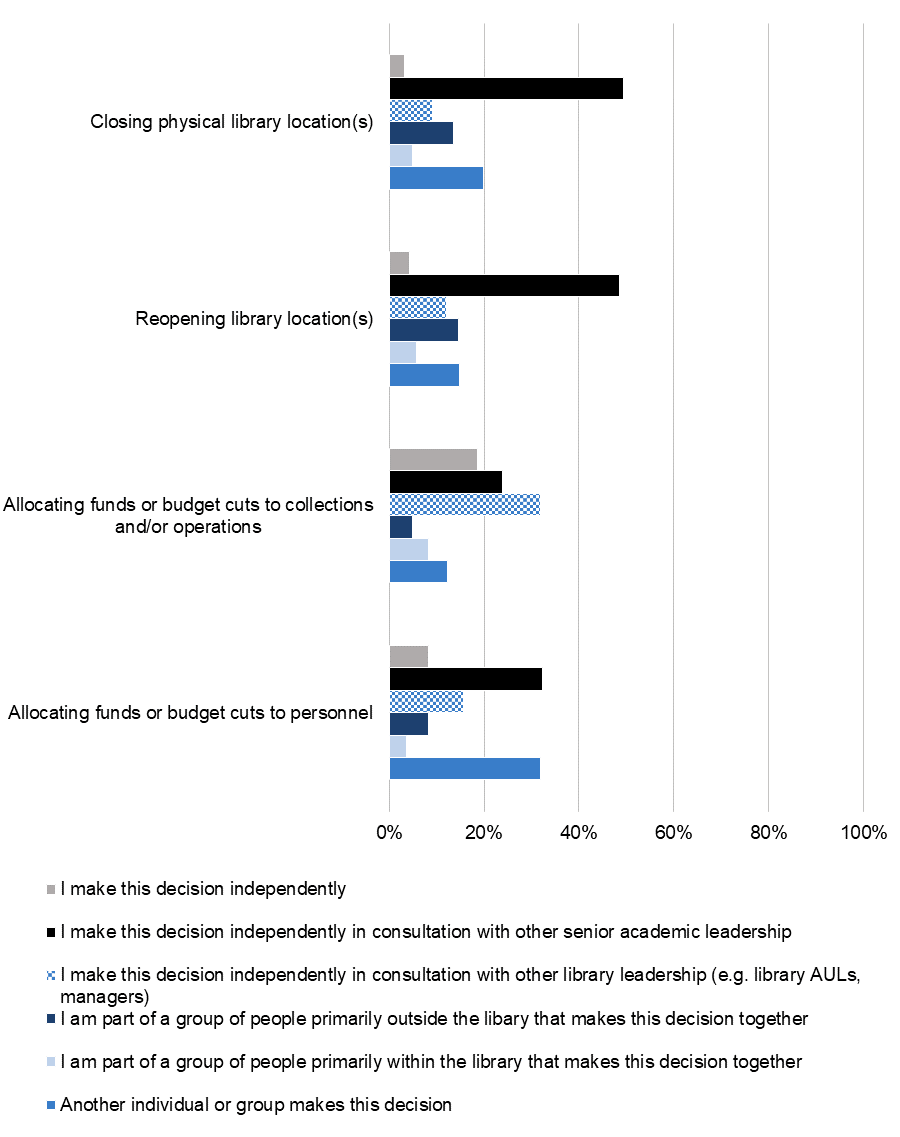

While library leaders generally had a great deal of discretion in making decisions about closing and reopening physical library locations, input from other senior academic leaders was much more frequently factored into budgetary decisions. Nearly half of directors made decisions to close and/or reopen physical library locations independently in consultation with other senior academic leadership. This was the most common approach for all respondents regardless of their institution type. See Figure 3. However, baccalaureate and master’s institution directors were about twice as likely to have these decisions made by another group (17-25 percent) compared to doctoral university directors (9-11 percent) who in turn were more likely to make the decisions completely independently (6 percent for each compared to 2-5 percent). As doctoral university directors are more likely to be considered part of their institution’s senior academic leadership, as has been well-documented over time in this survey series, they in turn were given more latitude in making decisions pertaining to the library’s operations during the pandemic.

With respect to allocating funds and/or making budget cuts to collections and operations, library directors most commonly made decisions entirely on their own or fairly independently in consultation with other leaders within or outside of the library (74 percent combined). When it comes to financial decisions regarding personnel, however, only about half make decisions independently or independently in consultation with these groups (56 percent combined). In fact, for about three in ten directors, another group makes decisions pertaining to personnel allocations and cuts for them altogether. Doctoral university directors have made many of these decisions relatively more independently, while baccalaureate and master’s institution directors are more likely to have these decisions made on their behalf, especially those related to personnel.

These decisions are not made independently of each other, however. While directors often have at least some say in whether or not to close the physical library location, for example, their decision to do so or not has implications for the decisions made in allocating funds to personnel. It may be harder to justify keeping staff whose work depends on the physical library on the job rather than furloughing them, for example, if the library location is closed. Thus, even when library directors make decisions independently, they still must consider how their decisions will impact other decisions that are made by committee.

Figure 3. Which of the following statements best describes your role in making decisions for the library in each of the following areas during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Percentage of respondents that selected each response option.

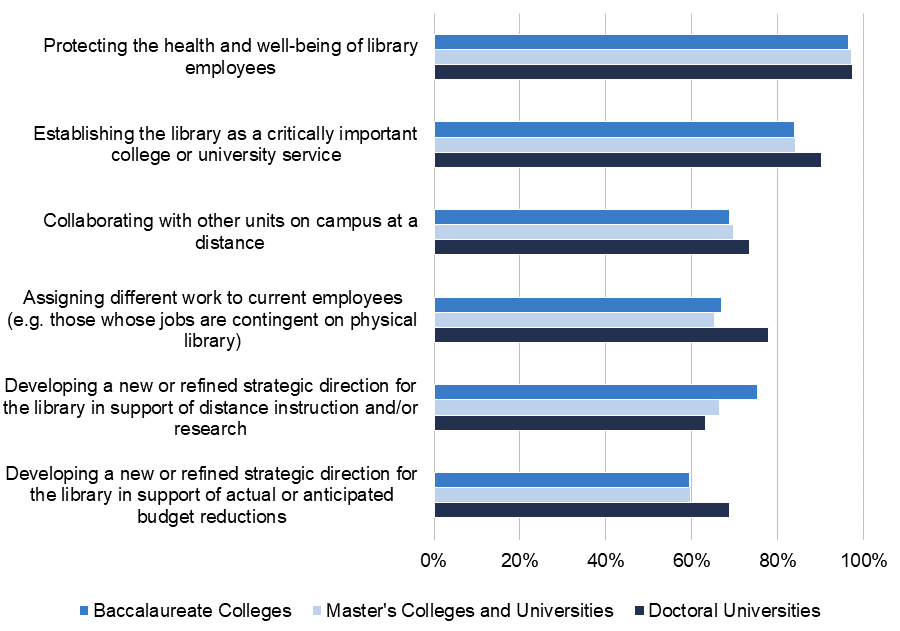

In making these decisions related to spaces, operations, and budgets, there were many factors for library directors to consider. The vast majority (97 percent) indicated that protecting the health and well-being of library employees was highly important. This priority likely contributed greatly to decisions on closing and reopening physical library locations. Establishing the library as a critically important college or university service was also viewed as highly important by the vast majority of respondents (86 percent). See Figure 4. In many conversations leading up to this survey, we heard directors express the importance of—and sometimes the tension between —ensuring staff well-being while also providing service continuity for campus communities, thereby establishing the library as essential.

A greater share of doctoral university library directors prioritized assigning different work to current employees than they might typically work on before the start of the pandemic (77 percent compared to 65-67 percent at baccalaureate and master’s institutions), signaling a desire to avoid furloughs and job cuts when possible. On the other hand, about three-quarters of baccalaureate college library directors considered it highly important to develop new directions for distance instruction and/or research compared to only 63 percent of doctoral university directors, perhaps due to a relative underinvestment to date in these directions.

Figure 4. How important have each of the following activities been to date in planning for library operations and services during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Percentage of respondents that selected highly important.

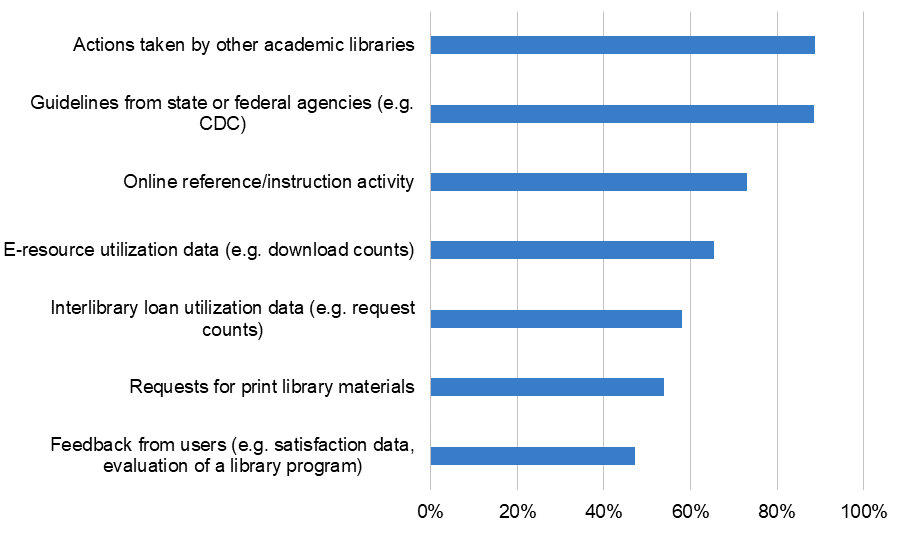

In making these decisions, library directors collected or consulted data and information from a variety of sources as shown in Figure 5. The two pieces of data consulted by the most library directors were from external sources, including actions taken by other libraries and guidelines from state or federal agencies such as the Center for Disease Control (89 percent of library directors consulted each). These two sources coincide with the activities most directors shared as highly important. Protecting the health and well-being of their employees relates to the Center for Disease Control data and establishing the library’s collections and services as critically important corresponds to data from other libraries. As the COVID-19 pandemic has been an unprecedented challenge for leaders across higher education, directors have often turned to others—their peers and relevant agencies—for input to guide their thinking.

There are differences in data consultation across different types of institutions. As doctoral university libraries typically have more general and assessment-specific resources available to them, often including dedicated roles for library assessment professionals, it is not surprising that they collect and/or consult e-resource utilization data and feedback from users at a greater rate than baccalaureate and master’s institution directors (72 percent vs 59-66 percent and 58 percent vs 39-45 percent respectively).

Figure 5. What types of data or information have you gathered and/or consulted to inform decision making at your library during the COVID-19 pandemic? Please select all that apply or leave the question blank if none of the items apply.

Percentage of respondents that selected each item.

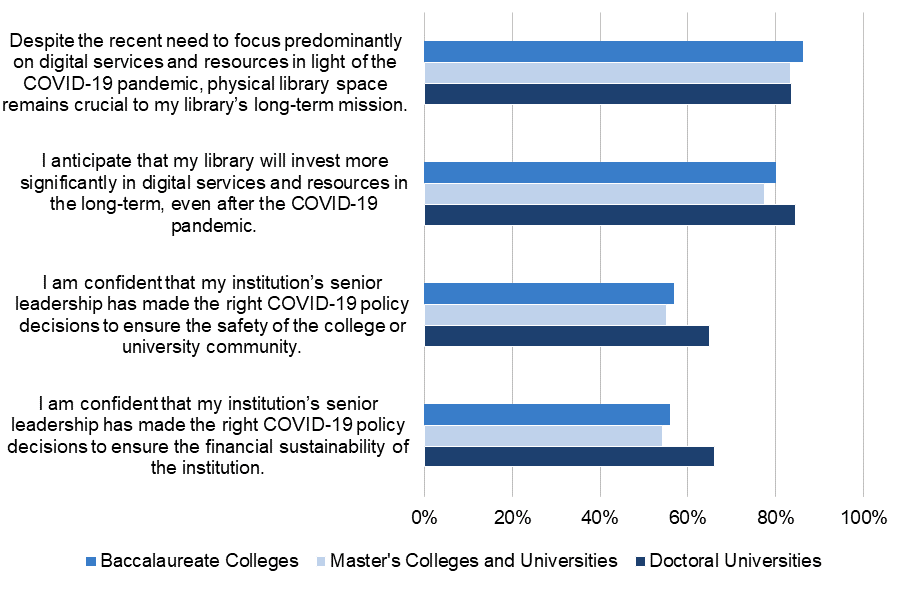

Library directors also answered questions about their parent institution’s response to COVID-19 more broadly. More than half of directors reported that they are confident that their institution’s senior leadership made the right decisions to ensure both the physical safety and the financial security of the institution (58-59 percent). A greater share of doctoral directors was confident in these decisions, perhaps because they were more involved in institutional decision-making themselves or there was more public health expertise available within the university. See Figure 6. Further, a smaller share of library directors at Midwestern institutions were confident that their institutions made the correct decisions to ensure the safety of the campus community compared to those at institutions in the Northeast and West of the United States (45 percent compared to 66-69 percent). As the Northeast and West were areas hit hard earlier on in the pandemic, perhaps they established safety protocols more quickly than elsewhere.

Library priorities have shifted to accommodate increased remote research, teaching, and learning during the pandemic. Indeed, many more library directors reported prioritizing special services for students enrolled in online or hybrid courses compared to what was found in the prior survey cycle (59 percent in 2020 compared to 42 percent in 2019). However, while most directors anticipate that they will invest more in digital services and resources in the long-term, they also expect that the physical library location will remain crucial to the library’s mission. In other words, there is no indication that a continued investment in digital resources and services will be at the expense of reductions to library space and associated in-person operation even as the institution as a whole also shifts more toward the digital. With many students in particular struggling to access technology and find quiet spaces for coursework this year, it is no surprise that directors continue to see value in their in-person service provision for addressing these needs.[4]

Figure 6. Please use the 10 to 1 scales to indicate how well each statement below describes your point of view.

Percentage of respondents that strongly agree with each statement, by Carnegie Classification.

Budget

COVID-19 has endangered finances in many sectors, including higher education, so we included a set of questions about how the pandemic has specifically impacted library budgets. We examined both actual budget cuts and how these are being applied, as well as projected budget cut scenarios. We also asked library directors how temporary or permanent they expected such reductions to be.

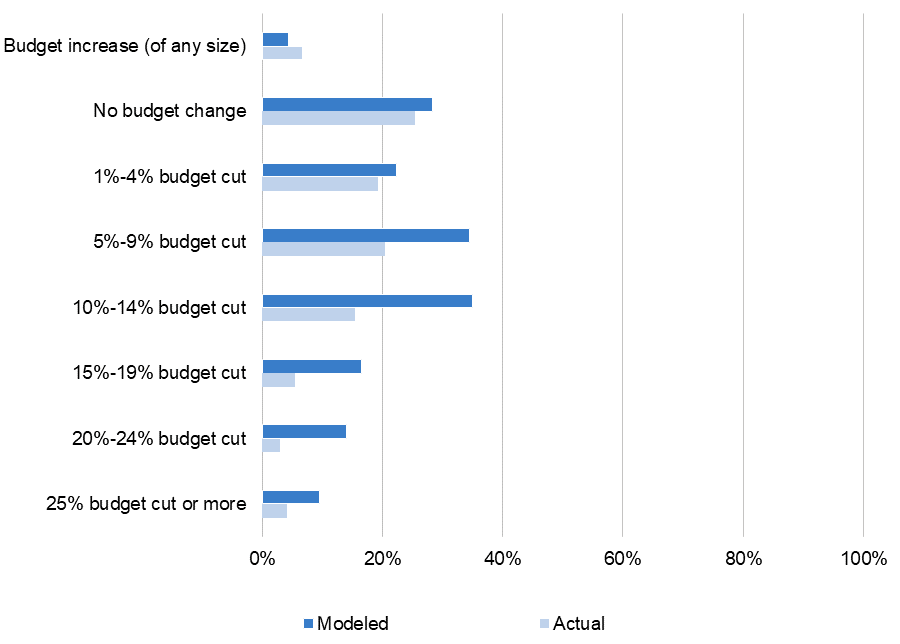

Library directors considered a wide range of budget cuts as they were planning for the 2020-2021 fiscal year. The most commonly modeled scenarios were overall budget cuts of 10-14 percent and 5-9 percent with just over one-third of library directors modeling each of these. Of those whose budgets were determined by the time of the survey in September, 75 percent had received budget cuts of any size, and these cuts were slightly lower than the modeled scenarios, with the greatest shares (19-21 percent of these libraries) falling in the 1-4 percent and 5-9 percent budget cut ranges. See Figure 7. While these cuts were smaller than expected, it may be that those without an academic year budget will experience above-average cuts, and in any case further cuts in the 2021-2022 fiscal year are likely.

Further, libraries that experienced the highest level of cuts (25 percent or more) in the 2020-2021 fiscal year, which was about equally common across institution types, are disproportionately more likely to have had decisions about fund allocations for collections, operations, and personnel made for them by another group (33-52 percent of those with the highest levels of cuts; 16-37 percentage points more than those who had lower levels of cuts). This could indicate that in cases where institutional funding was most limited, high levels of cuts needed to be made regardless of input from library directors, or perhaps that in cases in which library directors were not given the opportunity to advocate for the library, bigger cuts were made.

In 20 percent of libraries, the actual budget for fiscal year 2020-2021 had not been determined by the time of the survey. A greater share of these considered more substantial budget reductions—in particular, cuts of 10-14 percent and 5-9 percent (49 percent and 37 percent respectively)—compared to those whose budgets had been determined. This suggests that for libraries where a full picture of the budget has not yet been determined, there is a greater likelihood of larger cuts once their budget is determined. Many directors may be subject to institutional expenditure controls, instructed not to spend any unnecessary money as the impacts on revenue were still being determined.

Figure 7. When modeling for the 2020-2021 fiscal year in light of the financial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, which of the following overall library budget scenarios did you consider or were you asked to consider?[5] / How does the actual budget for the 2020-2021 fiscal year compared to what you would have otherwise expected before the COVID-19 pandemic? Please select the item below that currently best describes the percentage change.[6]

Percentage of respondents that selected each item.

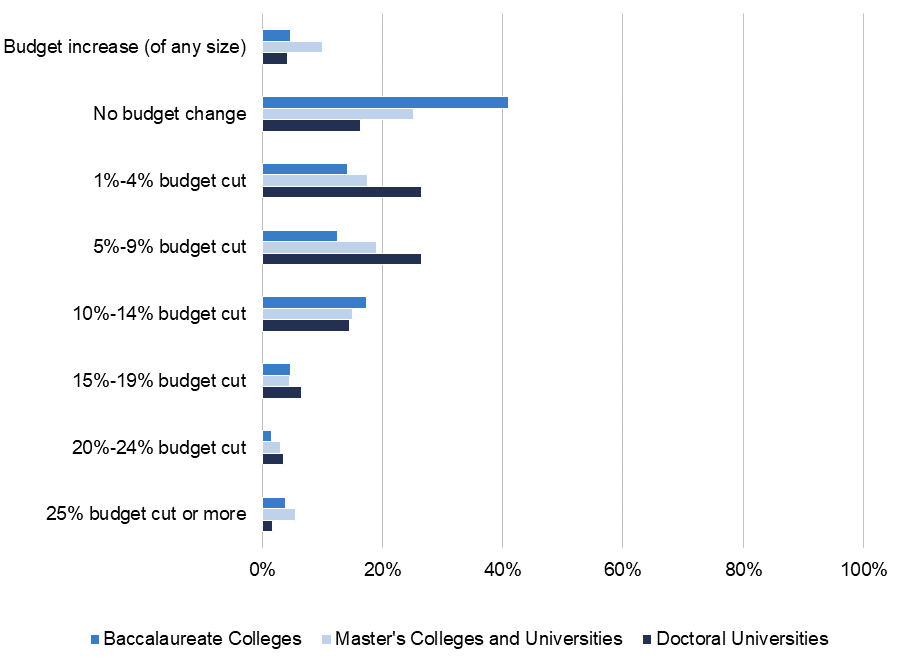

At nearly half of the baccalaureate college libraries in which budgets had been determined, there were no budget cuts (including both budget increases of any size and no change), while at master’s institutions and doctoral universities this was much less likely (46 percent vs 35 percent and 21 percent respectively). See Figure 8. A lack of budget reduction was particularly common at private baccalaureate colleges, with 51 percent having no budget cuts compared to 30 percent of public baccalaureate colleges.[7] This pattern held for master’s institution libraries but not doctoral university libraries, the latter of which had similar proportions of libraries with no budget cuts across the sector types (21 percent at public and 19 percent at private doctoral university libraries). While budget cuts were more common at doctoral university libraries, they were specifically more likely to have the smallest levels of budget cuts in our survey, 1-4 percent and 5-9 percent (53 percent combined compared to 27-37 percent at baccalaureate and master’s institutions). Although doctoral university libraries came in to the pandemic with higher overall budgets, they were by no means unaffected by the financial impact of COVID-19.

Figure 8. How does the actual budget for the 2020-2021 fiscal year compared to what you would have otherwise expected before the COVID-19 pandemic? Please select the item below that currently best describes the percentage change.[8]

Percentage of respondents that selected each item, by Carnegie Classification.

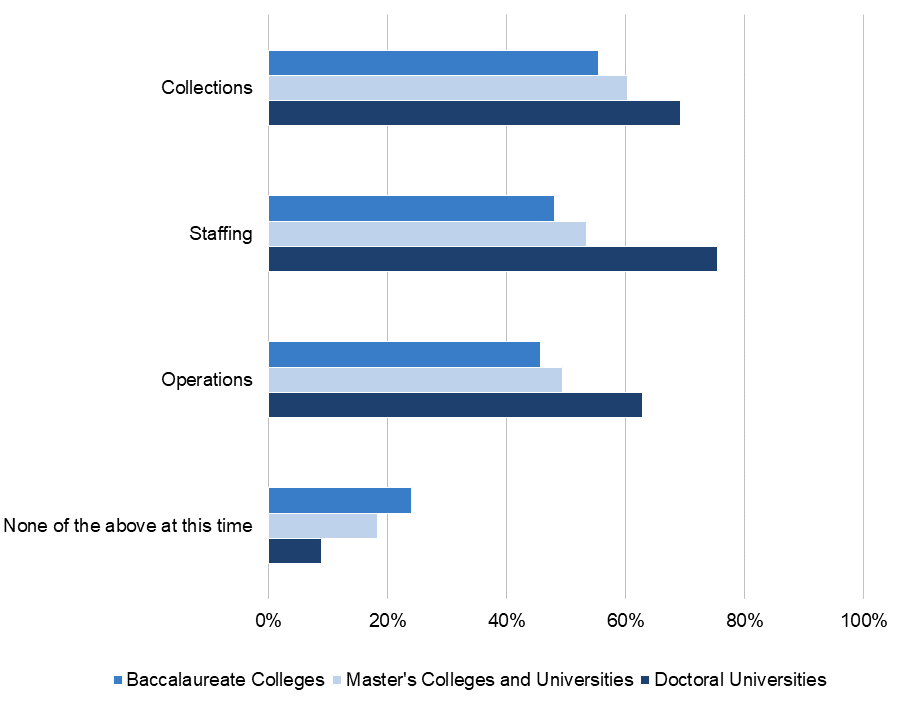

Since most directors faced some level of budget cuts, they needed to decide how to allocate those cuts. The majority of directors cut from each of the three areas we asked about: 62 percent made cuts to collections, 59 percent allocated cuts to staffing, and 53 percent cut funds from operations. Overall, only 17 percent made cuts from none of these. Since a majority of directors made cuts in each area, when budget cuts did happen, they generally happened across multiple expense areas. In each of these cases, a greater proportion of library directors at doctoral universities made cuts, with the biggest differences across institution types for cuts made to staffing. See Figure 9. At public institutions, a greater share made cuts to both staffing and operations (60-68 percent for public and 47-52 percent for private institutions) but not collections.

Figure 9. In which of the following areas has the 2020-2021 fiscal year budget decreased or do you anticipate will decrease compared to what you would have otherwise expected before the COVID-19 pandemic?

Percentage of respondents that selected each item, by Carnegie Classification.

For those who did make budget cuts in one or more of these areas, the cuts were similar in size across the different areas. The biggest cuts were for collections, averaging a 16 percent reduction, while the smallest cuts were for operations, averaging a 12 reduction; staffing fell in between, with a 14 percent cut. While some directors may have focused cuts on one of these areas, it appears that many have had to make cuts across the library budget. Further, in the 2020 survey library directors selected a lack of financial resources as one of their top three constraints at a similar rate to those in the 2019 survey. This indicates that financial concerns were already top of mind prior to the pandemic. Thus it is possible that cuts to collections, staffing, and operations would have happened regardless of the pandemic although the cuts may not have been as large.

Library directors simply do not know whether these budget cuts will be temporary or permanent. When asked if they anticipated their budgets to recover in the long-term, responses were very spread out across response options with nearly half indicating that they were unsure. An additional 27 percent anticipated the effects to be temporary while 24 percent expected more long-term financial effects. The budgetary uncertainty that library directors (and all university leaders) are facing for the future is undoubtedly complicating planning for the library itself, as well as its workers and users.

Acquisitions

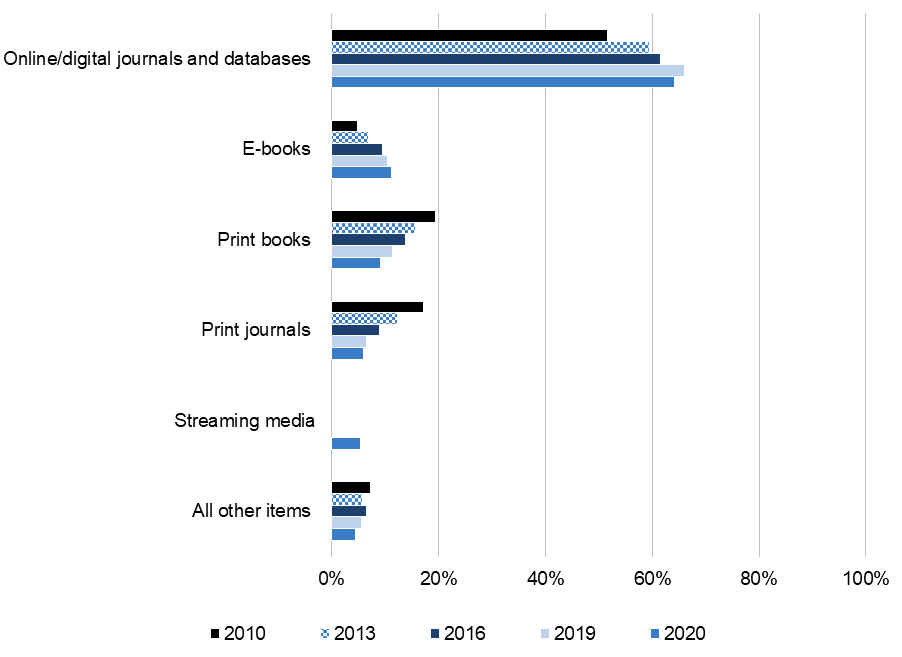

In this section, we pay special attention to the impact of COVID-19 on library materials budgets. Since the first triennial library survey in 2010, we have asked library directors about the percentage of their materials budget that is allocated to different collections types. Over time, the percentage allocated to print resources, including both print books and print journals, has steadily decreased while the percentage allocated to electronic versions of these resources has continuously increased. In the 2020 survey, we added a category for streaming media.[9] See Figure 10.

As of 2019, the average percentage spend on e-books approached that for print books for the first time. This year, spending on e-books overtook print books. With physical building closures and reduced capacities, the need for electronic resources has only increased.

Figure 10. In the 2020-2021 academic year, what percentage of your library’s materials budget is allocated to the following items? Percentages must add to 100 percent.

Average percentages across all participants, by survey cycle.

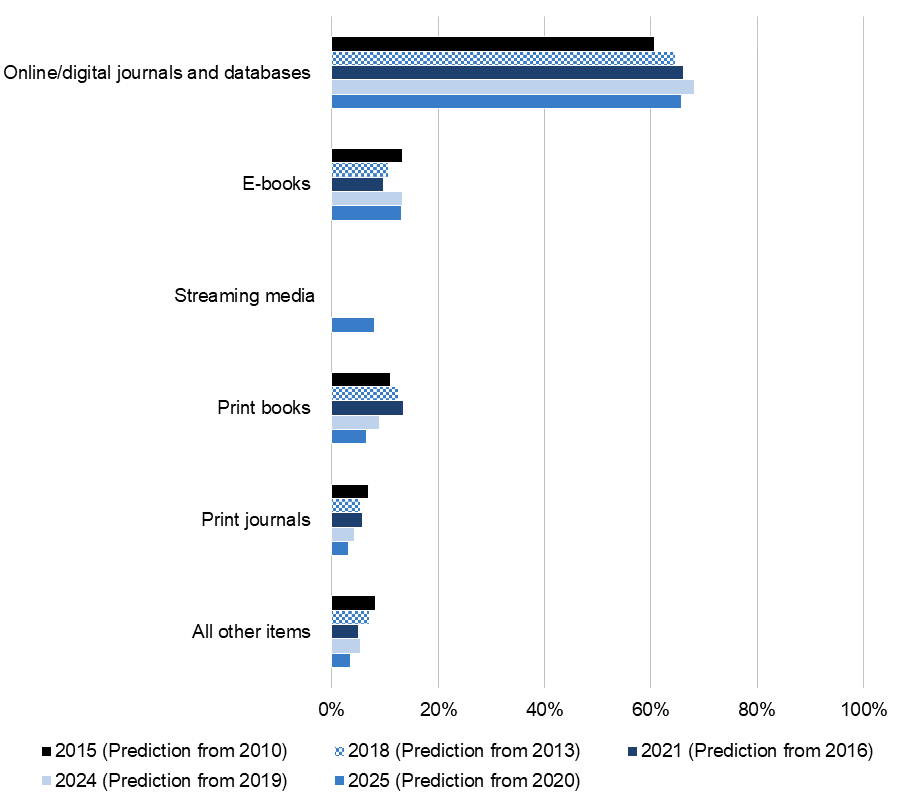

The COVID-19 pandemic may have accelerated the format transition from print to electronic resources. By 2025, they anticipate spending almost twice as much on e-books as they do on print books (13 percent vs 7 percent), for example, a gap that has grown substantially in just this past year. This pattern holds for all Carnegie Classifications and for both public and private institutions. See Figure 11. They also expect to increase the percentage of their materials budget allocated to streaming media from 5 percent in 2020 to 8 percent by 2025, making up the third biggest share of the materials budget following online journals/databases and e-books.

Figure 11. In five years, what percentage of your library’s materials budget do you estimate will be spent on the following items? Percentages must add to 100 percent.

Average percentages across all participants, by survey cycle.

In 2019, we asked for the first time whether library directors plan to cancel one or more major journal packages. This survey cycle, given the substantial attention that Unsub and an unbundling strategy have both received,[10] we added an additional question asking if they expected to unbundle one or more of these packages. A slightly smaller share of directors reported anticipating canceling journal packages this year compared to 2019 (42 percent vs 47 percent), and relatively fewer expect to unbundle (39 percent). However, doctoral university library directors anticipate unbundling at a higher rate than baccalaureate and master’s institution library directors (52 percent, 30 percent, and 33 percent respectively). There is also a strong correlation between these two practices, suggesting that those who expect to cancel packages also expect to unbundle them and keep a smaller number of particularly important or frequently used journals (r = .74). Although most directors allocated budget cuts to collections, as shown above, it does not appear that the pandemic made them more likely to cancel journal packages, but rather that additional cuts were likely made in other areas such as with print materials.

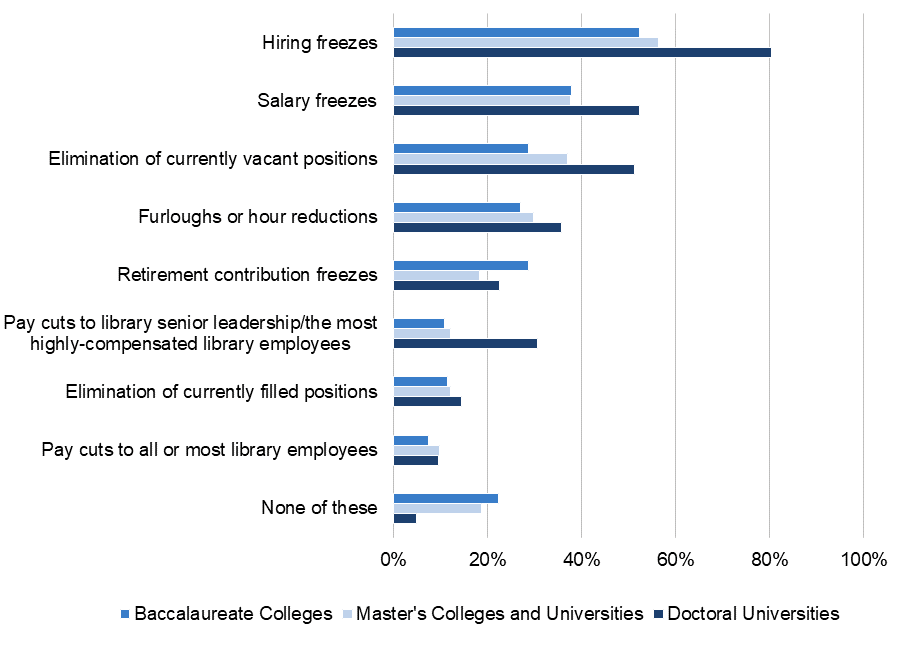

Staffing

Finally, we explore how COVID-19 impacted library employees from the director’s perspective. To get a sense of the major staffing changes made due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we asked directors to indicate which of a variety of personnel and benefits reductions were employed. Overall, 85 percent of institutions made at least one type of reduction. The most common were hiring freezes (63 percent), salary freezes (43 percent), and elimination of currently vacant positions (40 percent). See Figure 12. Two of these pertain to positions that were not yet filled, while one more directly impacts current staff. Even when changes were made that affected current employees, steps were taken to minimize the negative impact by halting pay increases rather than reducing salaries when possible.

When library employees are unionized, there are an additional set of contractual provisions—or sets of provisions when multiple unions exist across different classifications of employees—that affect potential personnel cuts. As such, there are correlations, albeit small, between the percentage of staff who are unionized and staffing changes such as hiring freezes, elimination of currently vacant positions, and retirement contribution freezes. Hiring freezes and elimination of currently vacant positions are positively correlated with unionization such that library directors were more likely to report these types of changes when a greater share of employees are unionized (r = .11 and r = .14 respectively). Retirement contribution freezes, on the other hand are negatively correlated with the degree of unionization (r = -.16). Thus, when a greater percentage of staff are unionized, retirement contributions are frozen less often.

Similarly, librarian faculty status places limitations and protections on personnel changes that an institution can make. In institutions where librarians have faculty status, a smaller share of library directors reported salary freezes and retirement contribution freezes compared to libraries without faculty status granted (39 percent vs 48 percent and 15 percent vs 29 percent respectively). In libraries with greater unionization and faculty status, institutions are prioritizing protections for current employees with these privileged statuses limiting the ways budget cuts can be allocated to staffing. This leaves employees without these protections more vulnerable to changes.

As with overall budgets, where doctoral universities cut their library budgets most steeply than at smaller institutions, so doctoral university libraries have seen a higher rate of personnel and benefits reductions, reflecting institutional differences in volume of staff and pay scales. In particular, a much larger share of doctoral university library directors reported hiring freezes (80 percent vs 52-56 percent), salary freezes (52 percent vs 38 percent each), elimination of currently vacant positions (51 percent vs 29-37 percent), and pay cuts to library senior leadership/the most highly-compensated library employees (31 percent vs 11-12 percent).

Figure 12. In light of the financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which of the following changes have been made with regards to library staffing and benefits?

Percentage of respondents that selected each item, by Carnegie Classification.

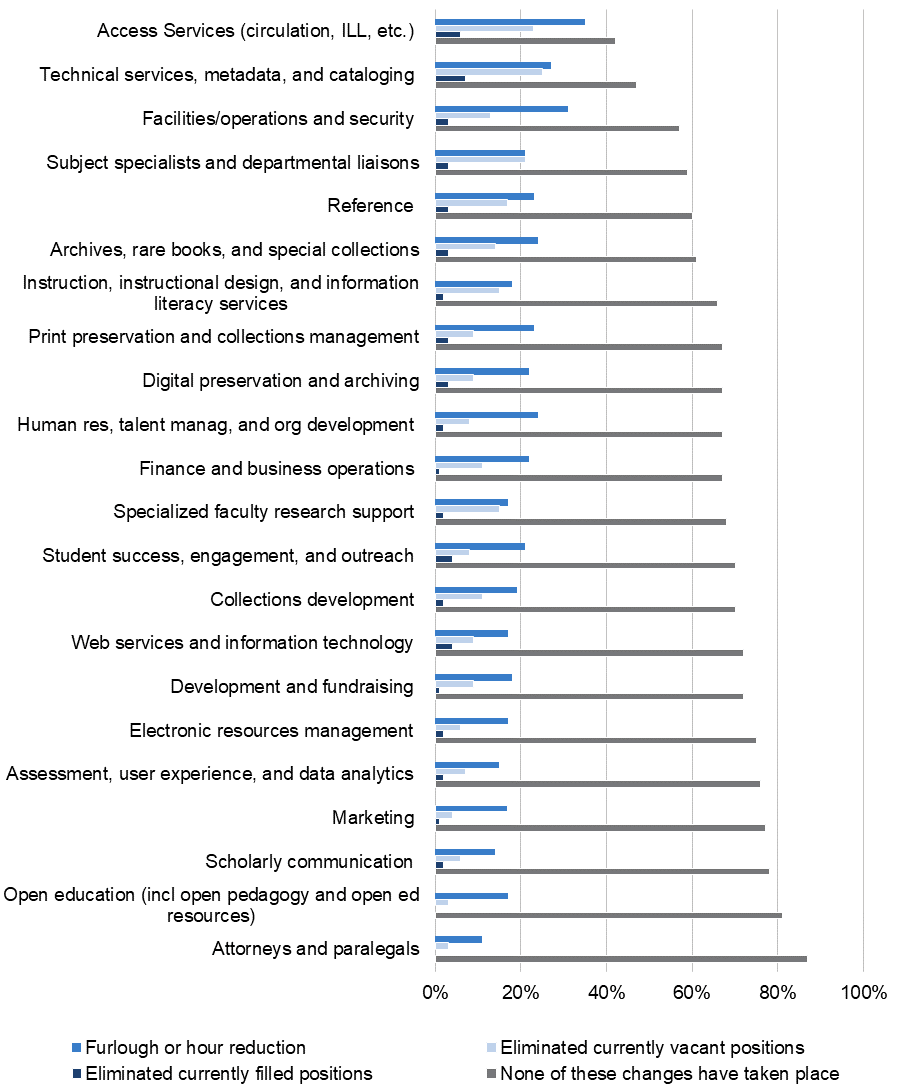

We asked library directors who furloughed, reduced hours, or eliminated current or vacant positions to share which employee positions were most affected.[11] Personnel cuts are widespread across many different kinds of positions. See Figure 13. The three areas most impacted were access services; technical services, metadata, and cataloging; and facilities/operations and security. Many of the individuals in these roles are dependent on the library physical space. Therefore, as physical locations closed and reduced hours, and as budget cuts were made, these areas took the hardest hits.

Figure 13. In light of the financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, what changes to employee positions in each of the following areas have been made?

Percentage of respondents that selected each item within each job category.[12]

Although, it was slightly more common to eliminate currently vacant positions than it was to furlough employees, for each job category furloughs were selected at the highest rate. This indicates that furloughs are spread out across different employee positions to a greater extent. As furloughs are generally an across the board effort to reduce compensation when organizations are not prepared to eliminate positions or make other changes, this is not surprising. Further, elimination of currently filled positions was much less common overall and only appeared to be used as a last resort, although it was slightly more common in access services and technical services.

Student employee positions were affected as well. There were differences in responses by institution type, but overall, the majority of directors across all institutions decreased student employee positions and/or hours. At doctoral universities, where a greater number of student employees were employed prior to the pandemic, a greater share reported decreasing positions or hours (82 percent compared to 63-64 percent at baccalaureate and master’s institutions). In the majority of the remaining cases, student employee positions and hours remained the same. Only 4 percent of library directors increased student positions or hours. Although various reductions to full-time, permanent employee positions were made, these positions were not replaced by part-time or lower-cost student employee positions.

Just over half of library directors anticipate being more flexible with allowing employees to work from home after the pandemic. Doctoral university library directors, likely due to their larger volume of employees who are able to cover in-person positions when someone else works remotely, were more likely to envision sustaining this flexibility compared to baccalaureate and master’s institution library directors (71 percent vs 47 percent each). As the pandemic continues it is likely that at least some employees at all institution types will be able to work remotely, identifying the steps needed to do so moving forward if needed.

Conclusion

Results from the Library Survey 2020 provide a glimpse into how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed academic libraries in the United States. While directors have had to adjust to a variety of resource constraints and unprecedented circumstances, it appears that the library and director role are perceived to be valuable and well-positioned to face the challenges of supporting emergency remote teaching, learning, and research. Library directors realized the value of skills in managing change and communicating effectively and continued to move toward greater provision of digital resources and services. Many led and contributed substantially to decisions that impacted the library and institution more broadly.

Library directors worked to prioritize employee safety along with the financial security of the library, though many had to make substantial cuts to staffing along with collections and operations. Taken together, all of these concerns have provided a particularly difficult environment for library directors, library employees, and others in the higher education sector.

We will continue to analyze and report on the results of the Library Survey 2020 in our upcoming report on findings related to equity, diversity, inclusion, accessibility, and anti-racism. In the meantime, we look forward to hearing your thoughts, reflections, and questions on this latest cycle of findings.

Appendix A: Methodology

As in previous cycles, we generated a list of US institutions from the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education database to sample from in the 2020 survey.[13] One individual from each institution was chosen as the contact person for the survey. Our final list of contacts included 1,504 library directors.[14] Of the 1,504 individuals we attempted to contact, 31 emails bounced or failed. This brought our total population of invited directors to 1,473.

An initial invitation and three reminder messages were sent in September 2020. Roger Schonfeld, director of Ithaka S+R’s Libraries, Scholarly Communication, and Museums Program, Christine Wolff-Eisenberg, manager of surveys and research at Ithaka S+R, and Trevor A. Dawes, vice provost for libraries and museums and May Morris University Librarian at the University of Delaware were the signatories of the messages.

Of the 1,473 directors who received emails inviting them to participate in our survey, we received completed responses from 638, for an overall response rate of 43 percent. As in previous cycles, response rates from doctoral universities were highest. The data in this report have not been weighted or otherwise transformed in any way, so we ask the reader to bear in mind that response rates differed to some degree by institutional type.

The Ithaka S+R Library Survey 2019, as well as previous cycles in 2016, 2013, and 2010, served as a starting point for the 2020 cycle. A group of external advisors provided input on current trends in academic library—most importantly the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and movements for racial justice—and corresponding questions were added to the instrument. Since we asked survey participants to respond during the COVID-19 pandemic, we also cut a number of questions to reduce the length of the survey. After incorporating feedback from advisors on a draft instrument, we tested the survey via cognitive interview with six additional library directors and made final revisions based on their feedback.[15] The final survey included randomization on the order of items within question sets as well as display logic on a few items such that they would only display to participants if they selected particular responses.

Finally, we employed a variety of techniques to analyze the data for this report. To identify the distribution of responses at a high level, we ran frequency or descriptive analyses (averages) on each response option for each survey question. These were computed on both the aggregate and subgroup data (e.g. by Carnegie Classification). These analyses were used to create the figures in this report.[16]

Additional subgroup analyses were performed for groups with at least 30 respondents. Using these, we ran independent samples t-tests, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD tests, and chi-square analyses when appropriate. Results of these analyses are reported throughout this report if they are statistically significant at the p <.05 level. We have also noted the frequencies of responses over time, paying particular attention to large differences.

Datasets from the 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2019 cycles of the Library Survey have been deposited with ICPSR for long-term preservation and access.[17] We intend to deposit the 2020 dataset in a similar fashion. Please contact us directly at research@ithaka.org if we can provide any assistance in accessing and working with the underlying data.

Appendix B: Participant Demographics

| Population Demographic | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Carnegie Classification | ||

| Baccalaureate Colleges: Mixed Baccalaureate/Associate’s | 13 | 2% |

| Baccalaureate Colleges: Diverse Fields | 57 | 9% |

| Baccalaureate Colleges: Arts & Sciences Focus | 106 | 17% |

| Master’s Colleges & Universities: Small Programs | 35 | 6% |

| Master’s Colleges & Universities: Medium Programs | 73 | 11% |

| Master’s Colleges & Universities: Larger Programs | 137 | 21% |

| Doctoral/Professional Universities | 51 | 8% |

| Doctoral Universities: High Research Activity | 71 | 11% |

| Doctoral Universities: Very High Research Activity | 79 | 12% |

| Sector | ||

| Public, 4-year or above | 264 | 42% |

| Private not-for-profit, 4-year or above | 360 | 58% |

| Current course status | ||

| Classes are being held primarily in person | 85 | 13% |

| Classes are being held roughly evenly online and in person (including “hyflex” / hybrid models) | 329 | 52% |

| Classes are being held primarily online | 200 | 32% |

| Other (please specify): | 21 | 3% |

| Current library status | ||

| Library/libraries open usual fall semester/term hours | 170 | 27% |

| Single / only library location open but hours are now limited compared to usual | 239 | 38% |

| Multiple-location library open but hours are now limited and/or some locations closed compared to usual | 130 | 20% |

| Library / all libraries closed | 58 | 9% |

| Library hours have expanded compared to usual | 0 | 0% |

| Other (please specify): | 39 | 6% |

| Enrollment changes | ||

| Increase (of any size) | 149 | 23% |

| No change | 91 | 14% |

| 1-4% decrease | 189 | 30% |

| 5-9% decrease | 96 | 15% |

| 10-14% decrease | 44 | 7% |

| 15-19% decrease | 15 | 2% |

| 20-24% decrease | 7 | 1% |

| 25% decrease or more | 4 | 1% |

| Not sure / enrollment for the fall semester/term has not yet been determined | 41 | 6% |

| Job title | ||

| Director | 333 | 52% |

| Dean | 196 | 31% |

| Chief, head, college, or university librarian | 103 | 16% |

| Other (e.g. vice provost, vice president, professor) | 59 | 9% |

| Direct supervisor | ||

| Provost, chief academic officer, or vice president of academic | 511 | 80% |

| Deputy/Assistant/Associate provost, deputy/assistant/associate chief academic officer, or deputy/assistant/associate dean of academic affairs | 73 | 12% |

| Chief Information Officer (CIO) | 16 | 3% |

| College or university president | 10 | 2% |

| Other | 26 | 4% |

| Approximately what percentage of employees at your library are unionized? | ||

| 0% | 458 | 72% |

| 1-25% | 34 | 5% |

| 25-50% | 34 | 5% |

| 51-75% | 29 | 5% |

| 76-100% | 82 | 13% |

| Do librarians at your library have faculty status? | ||

| Yes | 350 | 55% |

| No | 213 | 34% |

| Other (please specify): | 72 | 11% |

| Teaching and research balance | ||

| My institution is primarily focused on teaching | 227 | 36% |

| My institution is somewhat more focused on teaching | 201 | 32% |

| My institution has an equal focus on research and teaching | 138 | 22% |

| My institution is somewhat more focused on research | 47 | 7% |

| My institution is primarily focused on research | 22 | 4% |

| Years as director at current institution | ||

| Less than 2 years | 133 | 21% |

| 2-5 years | 246 | 39% |

| 6-10 years | 132 | 21% |

| 11-15 years | 62 | 10% |

| More than 15 years | 63 | 10% |

| Previous position | ||

| Interim director | 120 | 19% |

| Director at another institution | 154 | 24% |

| Associate university/college librarian | 144 | 23% |

| Department head | 87 | 14% |

| Other position in higher education | 28 | 4% |

| Other position outside of higher education | 21 | 3% |

| Other | 81 | 12% |

| Age | ||

| 22-34 | 15 | 2% |

| 35-44 | 71 | 11% |

| 45-54 | 203 | 33% |

| 55-64 | 216 | 35% |

| 65 and over | 113 | 18% |

| Gender | ||

| Man | 221 | 36% |

| Woman | 395 | 64% |

| Non-binary | 3 | <1% |

| Another option not listed here | 1 | <1% |

| Transgender | ||

| Do you identify as transgender? - Yes | 3 | <1% |

| Race-ethnicity | ||

| White | 526 | 83% |

| Black or African American | 51 | 8% |

| Hispanic, Latino, Latina, or Latinx | 15 | 2% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 9 | 1% |

| Asian or Asian American | 8 | 1% |

| Middle Eastern or Northern African | 5 | 1% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 | <1% |

| Another option not listed here | 11 | 2% |

Endnotes

- For more on library operations throughout the spring and fall 2020 semesters, see: Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe and Christine Wolff-Eisenberg, “Indications of the New Normal: A (Farewell) Fall 2020 Update from the Academic Library Response to COVID-19 Survey,” Ithaka S+R, October 8, 2020, https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/indications-of-the-new-normal/. ↑

- These results, along with others on racial justice, equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility, will be explored in more depth in a second report on the survey’s findings. ↑

- See Jennifer K. Frederick and Christine Wolff-Eisenberg, “Leading the Library by Looking Beyond the Library,” Ithaka S+R, May 12, 2020, https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/leading-the-library-by-looking-beyond-the-library/, for more information on this trend. ↑

- Melissa Blankstein, Jennifer K. Frederick, and Christine Wolff-Eisenberg, “Student Experiences During the Pandemic Pivot,” Ithaka S+R, June 25, 2020, https://sr.ithaka.org/publications/student-experiences-during-the-pandemic-pivot/. ↑

- For this question, respondents were able to select all of the budget cut scenarios that they were asked to consider while they were only able to select one option to represent their actual budget cuts. ↑

- Excludes those who indicated that their 2020-2021 fiscal year budget had not been determined by the time of the survey. ↑

- This finding is perhaps counterintuitive given that private institutions, and private baccalaureate colleges in particular, have faced especially substantial net tuition revenue decreases; see for example Scott Carlson, “Colleges Grapple With Grim Financial Realities” The Chronicle, November 30, 2020, https://www.chronicle.com/article/colleges-grapple-with-grim-financial-realities. There are several potential reasons for the differences between overall institutional revenue declines and library budget cuts. Perhaps the most likely explanation for the differences by Carnegie Classification relate to the extent that directors at different types of institutions have control over their budgets. For example, given that baccalaureate college library directors have relatively less control over allocations in their budget than do those at master’s and doctoral institutions, it is possible that while the library was affected by certain types of budget cuts, these cuts were not captured as part of the library’s budget directly. It is also possible that given relatively lower rates of response from respondents at baccalaureate colleges, as has been consistent over time for the Library Survey, there is a greater chance of non-response bias. In other words, baccalaureate college library directors with more and/or higher budget cuts may not have responded to the survey. In our sample, we also had an overrepresentation of Oberlin Colleges. This overrepresentation does not appear to explain the result as the percentage of private baccalaureate colleges with no budget cuts increased when we removed Oberlin Colleges from our sample. ↑

- Excludes those who indicated that their 2020-2021 fiscal year budget had not been determined by the time of the survey. ↑

- The addition of the streaming media item could account for the slight decrease in the percentage library directors say has been allocated to online journals and databases compared to that of 2019 (64 percent; a 2 percent decrease). ↑

- Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe, “Taking a Big Bite Out of the Big Deal,” The Scholarly Kitchen, May 19, 2020, https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2020/05/19/taking-a-big-bite-out-of-the-big-deal/ ↑

- For the purposes of this report, we will focus on the aggregate findings by employee position. In our upcoming report on equity, diversity, inclusion, accessibility, and anti-racism findings, we will further explore how these areas relate to the overall racial-ethnic composition of libraries. ↑

- Only those who selected that they furloughed or reduced hours, or eliminated vacant or current positions in the previous question received this question. They only received the options they selected in the previous question (e.g. if they selected that they furloughed staff but did not eliminate positions, they only received the option to rate if they furloughed staff in each of the areas). Those who selected “N/A” for the given position were also excluded. ↑

- We included institutions from nine “basic” Carnegie Classifications: Baccalaureate Colleges: Mixed Baccalaureate/Associate’s, Baccalaureate Colleges: Diverse Fields, Baccalaureate Colleges: Arts & Sciences Focus, Master’s Colleges & Universities: Small Programs, Master’s Colleges & Universities: Medium Programs, Master’s Colleges & Universities: Larger Programs, Doctoral/Professional Universities, Doctoral Universities: High Research Activity, and Doctoral Universities: Very High Research Activity. ↑

- To get this total, we excluded 52 institutions for a variety of reasons: we were unable to collect contact information, the institution closed, the library director position was vacant, or the library did not have a director. ↑

- Christine Wolff-Eisenberg, “Employing Cognitive Interviews for Questionnaire Testing: Preparing to Field the US Faculty Survey” Ithaka S+R, June 1, 2018, https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/employing-cognitive-interviews-for-questionnaire-testing/. ↑

- In figures based on frequencies, we display responses at the high end of the scales used. For items with 10-point scales, frequencies of the top three response options (8-10) are displayed. We considered these responses to indicate strong agreement. Similarly, for items with 4—7 point scales, we display frequencies of the top two response options. ↑

- Datasets from the Ithaka S+R series of surveys may be found at “Ithaka S R Surveys of Higher Education Series,” ICPSR, http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/series/226/studies. ↑